By Sam McGowan

As the Japanese delegation stood on the deck of the battleship USS Missouri on September 2, 1945, preparing to sign the documents that ended World War II, a large formation of Boeing B-29 Superfortress heavy bombers swooped low over Tokyo Bay as a reminder of the terrible destruction that had befallen their nation and turned Japan’s cities into ruins. It was a reminder the Japanese really did not need—the bombed-out rubble and steadily smoking crematories around the country were evidence enough of the violent firestorm that had befallen the Land of the Rising Sun.

The national morale in Japan was so low that almost 70 percent of the people interviewed by U.S. military personnel after the surrender reported that they had reached the point where they were unable to endure one more day of war. Most Americans, especially the young soldiers and Marines who had been slated to invade the Japanese Home Islands of Kyushu and Honshu, believed that Japan surrendered because of the atomic bomb. They were wrong. In reality, the country had already been brought to its knees before the first atomic test at the Trinity Site in the New Mexico desert two months before. Japan had been destroyed by fire from above, fire that had largely been delivered from the bomb bays of an armada of Boeing B-29s.

The B-29 Deployment: A Political Decision

The B-29 had come to symbolize American air power by September 1945 because of the role it played in the final defeat of Japan, but the large four-engine bomber had originally been conceived as a weapon for use against Nazi Germany. The initial invitation for bid had been issued in the fall of 1940 as the War Department began preparing for a seemingly inevitable entrance into the war in Europe. Design problems and production delays kept the very long-range bomber out of service until it had become obvious that such range was no longer necessary against Germany. The first production B-29s began rolling off the assembly lines in mid-1943, prompting requests for the new bombers from commanders in each theater.

Lieutenant General George C. Kenney, the air commander in General Douglas MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific Area of Operations, was particularly insistent in his claims for the bombers. Not only had Kenney been short-changed in aircraft and crews because of the high priority given to the European Theater, but he had been heavily involved in B-29 development himself when he was in charge of Air Corps research and development at Wright Field near Dayton, Ohio, in 1941. Although Air Corps commander General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold was receptive to Kenney’s recommendations on use of the B-29s—the Southwest Pacific air commander wanted to use them from Australia, then from the Philippines—he had his own ideas as to where and how they should be deployed.

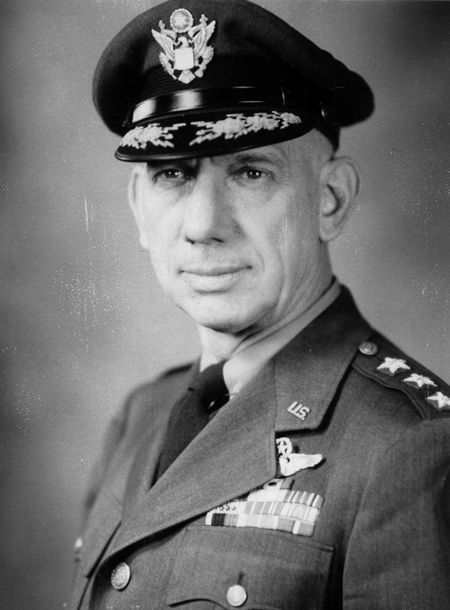

Arnold was also prompted by his own ambitions. In spite of his high rank and responsibility, he had never seen combat or commanded men in battle. Now he saw an opportunity for his own combat command. Instead of assigning the B-29s to the overseas air forces, he decided to establish a new air force under his personal command, a strategic bombardment unit headquartered in Washington, D.C. The new Twentieth Air Force would be controlled by Arnold’s own staff, which would select targets for the huge bombers and command the war from thousands of miles away.

The ultimate decision on deployment of the B-29s was based largely on political considerations, including appeasing President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s near-obsession with mounting an aerial bombardment campaign against Japan at the earliest opportunity. The liberal president was up for reelection to an unprecedented third term in 1944 and faced strong opposition from conservatives. The commencement of B-29 raids on Japan would boost his political stock.

“Early Sustained Bombing of Japan”

In spite of their long range, there were only four places in the world close enough to Japan from which B-29s could operate, and one of those, Soviet Siberia, was off limits because of Soviet neutrality in the war with Japan. Bases in the Aleutians were in range of Japan, but the horrific subarctic weather presented problems for the untried bombers. The Joint Chiefs of Staff saw potential for establishing B-29 bases in the Mariana Islands, a concept that pleased Admiral Ernest J. King, the Chief of Naval Operations, because such a move increased the importance of the Pacific Ocean Area of Operations, the only area under U.S. Navy command. King also favored Arnold’s plan for an independent command, as it would keep the B-29s away from Douglas MacArthur.

The third option was establishing B-29 advance bases in China, an option that would allow attacks on Japan to commence several months before bases could be established on the island of Saipan in the Marianas, and this was the option Arnold chose. Operations from China were also seen as a means of improving the morale of the Chinese people, who had been fighting the Japanese since 1931.

To command the first B-29s, Arnold selected Brigadier Kenneth B. Wolfe, an ideal choice since he was the project officer for the entire program and was intimately familiar with the airplane. Wolfe established the 58th Bombardment Wing (H) at Marietta, Georgia, where B-29s were being produced, then began training crews at Salina, Kansas. He drew up plans for operations from China called “Early Sustained Bombing of Japan” and given the code name Matterhorn. The Matterhorn plan called for the B-29s to be based in the vicinity of Calcutta, India, with forward operating bases established around Chengtu, China. It was an ambitious plan, particularly in terms of logistics, since all military operations in China were solely dependent on air transportation for supply.

Although there was an established airlift operation from India to China conducted by the Air Transport Command, Wolfe proposed that XX Bomber Command, the organization he would take to India, be entirely self-sufficient. The XX Bomber Command would include its own air transportation group equipped with older Consolidated B-24 Liberators that had been converted into C-87 transports and C-109 tankers. The B-29s would also be used as transports, and after they arrived in India several were converted into tankers to haul gasoline.

In an effort to maintain a degree of secrecy, the War Department took advantage of the B-29 development programs and put out a story that the planes had proven unsuccessful as bombers and were being converted into armed transports for duty in the China-Burma-India Theater. It is unlikely that the Japanese bought the story.

Operation Matterhorn’s Stormy Start

The first B-29 to depart for India went by way of England, where it was put on display for publicity purposes in an effort to indicate that the bombers would be used against Germany. B-29s began leaving for India in March 1944. By April they were flying transport missions from Calcutta to Chengtu. Matterhorn called for the first missions to be flown in June, and extensive preparations were made. Plans to airlift their own supplies proved optimistic, and the Air Transport Command was called on to provide additional air transportation. Supply problems were compounded in May when the Japanese went on the offensive in China and the theater commanders had a sudden increased need for supplies. They naturally took those that originally had been intended for Matterhorn, which had yet to fly the first combat mission.

The first B-29 mission, scheduled for mid-May, was an attack on the Makashan railroad yards in Bangkok, Thailand. Wolfe wanted to fly it at night since his crews had been engaged in transport operations and needed proficiency in formation flying and other combat tactics, but he was overruled by Arnold and the Twentieth Air Force staff, most of whom had come from the European Theater, where the emphasis was on daylight bombing. Arnold insisted that the first B-29 mission be a daylight precision attack.

Wolfe postponed the mission and instituted a training program. By June 5, 1944, Wolfe had 112 Superfortresses ready for the mission, but only 98 managed to get off the ground. One crashed immediately after takeoff. The weather was so bad that the B-24s that were supposed to participate in the attack canceled. Their commanders were not under pressure from the White House to perform, while reduced visibility and low clouds caused assembly problems for the B-29s. Fourteen B-29s aborted, and many of the crews failed to find the target. The remaining bombers were over Bangkok for an hour and a half, with each crew making its own decisions as to run-in and bombing altitudes. One navigator described the confusion as “Saturday night in Harlem.”

There was little enemy opposition, but monsoon thunderstorms made the return flight hazardous. Three B-29s failed to return because of fuel problems, while more than 40 made forced landings at airfields all over China. One crashed on landing, bringing the total losses to five brand-new B-29s and 17 crewmembers killed or missing. Post-strike photographs revealed minimal damage to the target. Nevertheless, Twentieth Air Force considered the first mission a success.

Hitting Japan’s Steel Industry

The very next day, Wolfe received an order from Arnold to mount an attack on a target in Japan by June 20. Wolfe faced a dilemma. His supplies at the Chinese forward fields needed replenishing. He had set a date of June 23 for a 100-plane mission and needed the extra three days. General Joseph Stilwell, the senior American officer in China, had diverted the supplies intended for Matterhorn operations from China to the Fourteenth Air Force. Wolfe wired Arnold that he could put up 50 planes on June 15 or 55 five days later. Arnold responded by ordering an attack with 70 airplanes on June 15; the order also demanded an increase in Hump airlift operations.

Twentieth Air Force had decided to mount a campaign against the Japanese steel industry, and the target for the first attack was the Imperial Steel Works at Yamata on the island of Kyushu. June 15 was the date for the impending invasion of Saipan, and Washington wanted to send a message to Tokyo that the end was drawing near. Wolfe managed to dispatch 92 B-29s to China, but nine arrived with mechanical problems. Each bomber was armed and ready for combat and would only need fuel and rest for the crews at the Chinese bases.

The mission order called for 75 airplanes but only 68 got off. One crashed and four aborted, leaving 63 to continue to the target. The first airplane reached Yamata just before midnight. The crew reported that the target was “Betty,” meaning the weather conditions were less than 50 percent cloud and that they had bombed. In spite of the good visibility, the steel mill was blacked out while smoke and haze obscured the ground. Only 15 crews were able to bomb visually, and 32 dropped their bombs using radar, a technique that at the time was considered inferior. There was strong fighter and antiaircraft opposition, but not a single B-29 was damaged over Japan, although one was lost over China during the return flight. Six B-29s were lost due to various causes, and 55 airmen were reported missing. Damage to the target was insignificant.

In spite of the lack of damage to the target, the mission produced results, causing the Japanese people to realize for the first time since the war began that they were in imminent danger. The following day, the War Department announced the existence of Twentieth Air Force, and the news of an attack on Japan competed with news from Normandy in the headlines. Arnold wired Wolfe that it was imperative that pressure against Japan be increased in spite of the logistical problems.

Immediate objectives were attacks on Japanese steel mills in Manchuria, harassing raids on Japan itself, and an attack on the Palambang oil refineries in Sumatra. Wolfe submitted a plan for a 50-plane mission against the Anshan steel works in Manchuria instead of the 100 that Arnold wanted and received a message that he was to return to the United States immediately for “an important assignment.” Wolfe was being “kicked upstairs,” with a promotion to major general and command of the Material Command, a move by Arnold to make way for a more aggressive commander.

With Wolfe gone, responsibility for XX Bomber Command operations fell to Brig. Gen. Laverne “Blondie” Saunders, the 58th Bombardment Wing commander. On July 7, an assemblage of 18 B-29s conducted a harassing mission against Japan. One aborted, but the other 17 managed to bomb “something.” Two were forced to turn back because of fuel transfer problems, but their crews dropped the bombs on the Japanese depot at Hankow in China.

Saunders decided that he would be able to mount an attack on Manchuria by postponing the Palembang mission. He received a major boost when July turned out to be a banner month for the Air Transport Command Hump operation, but he still faced a shortage of operational B-29s, a condition produced in part by the conversion of several to tankers. He proposed a halt to transport operations 10 days in advance of the raid and that the bombers begin moving up five days early, a move opposed by Fourteenth Air Force commander Maj. Gen. Claire Chennault out of fear the presence of the bombers would provoke Japanese attacks. Washington approved the plan, and the feared attacks failed to materialize.

Of 111 bombers dispatched from India, 107 reached China. Weather led to the attack being moved up a day to July 29. Rain kept one group on the ground, but 72 got off. Aborts and a crash reduced the number to 60 bombers over the target. Although weather conditions were ideal, the first bombs fell upwind from the target, and the smoke from the fires drifted over the mill. Fighters met the formation, and the B-29 gunners claimed three probables and four damaged. The 444th Group managed to get off when the rains let up to bomb targets at Tak and Chenghsien. One B-29 was lost after it was damaged by flak, then jumped by five fighters, one of which was an apparently captured Curtiss P-40 bearing the markings of the Chinese-American Composite Wing.

Matterhorn missions five and six ran jointly on the night of August 10, 1944, striking the Palembang oil refineries and the docks at Nagasaki. The double-barreled attacks were made possible by reducing the number of airplanes required for the Palembang mission. Washington originally wanted a daylight strike with a minimum of 112 planes, but fear of heavy losses led to a change to a dawn or dusk strike with half that number. Further negotiations gained permission for a night attack.

Part of the new plan called for mining the Moesi River, through which all of the complex’s exports were shipped. Eight 462nd Bomb Group minelayers went beneath a 1,000-foot ceiling to drop 16 mines “with excellent results.” One crew ditched with one casualty. The Palembang raid turned out to be the only mission flown out of Ceylon in spite of extensive preparation. The Nagasaki mission was considerably smaller, with only 24 bombers reaching the target. The mission was memorable in that gunner Technical Sergeant H.C. Edwards was credited with the first official B-29 confirmed aerial kill of the war against a Japanese plane. The mission went off surprisingly well, although the bombing results were indistinct because of poor quality photo intelligence. In spite of heavy flak and reports of 37 Japanese fighters, not a single B-29 was even scratched.

Saunders faced opposition from Chennault, who felt that attacks on the steel industry were fruitless. As the senior air officer in China, Chennault put forth an ultimatum that Matterhorn should either concentrate on the Japanese aircraft industry or withdraw to India. He considered the B-29s more of a liability than an asset in his theater as they used up valuable air transport space and their advance bases had to be defended. Saunders elected to ignore Chennault and continued planning attacks on steel targets.

On August 20, a total of 75 B-29s took off for Kyushu. One group was unable to get off until later in the day after a crash blocked the runway. Sixty-one B-29s hit the target in spite of intense opposition that claimed four bombers. Three were lost to what may have been a suicide attack when a fighter rammed the tail of one B-29 and the falling wreckage brought down two more. The 462nd Group managed to get its airplanes off the ground over the wreckage after lightening their loads for a night attack. Ten got over the target with little resistance. Still, the day was costly, with 14 bombers lost to various causes and 95 airmen killed or missing. Although XX Bomber Command believed the target was damaged, Japanese records indicated otherwise.

“Synchronous” Bombing

Saunders planned another attack on Manchuria, but before it was flown Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay arrived to take over XX Bomber Command. The mission was flown as planned, with LeMay going along to observe his crews in action. The attack resulted in considerable damage to the Showa Steel Works, but LeMay decided to institute new policies, including changing the basic formation from four planes to 12 to get a wider bombing pattern and consolidating the force into fewer groups with larger squadrons in a move to reduce support personnel and improve maintenance. He also instituted a new policy of “synchronous” bombing, with one bombardier staying on radar while the others attempted to acquire the target visually.

In spite of LeMay’s new policies, Matterhorn’s days were numbered. The XX Bomber Command only flew one more mission against a steel target, an attack on the Showa Works that produced absolutely no damage at all. Future missions were directed against Japanese aircraft industry targets and airfields on Formosa. Mining of rivers and harbors became a B-29 responsibility. In December, XX Bomber Command flew a mission that Chennault later claimed as a turning point. Since June, he had been pressing for a B-29 attack on the Japanese supply depot at Hankow with incendiary bombs but had been ignored by XX Bomber Command leadership.

After Japanese forces in China went on the offensive and threatened the Allied bases, Chennault renewed his efforts. He was supported by the new commander in China, Lt. Gen. Albert C. Wedemeyer. LeMay questioned Wedemeyer’s authority since he only commanded in China and the B-29s were in India, but Arnold agreed to the mission since he really had no other choice in view of the military situation in the region.

Incendiary Bombs on Hankow

The attack on Hankow was not the first B-29 incendiary attack of the war. Arnold had ordered experimental incendiary attacks from Saipan in November 1944, and a mission on the night of November 29 against Tokyo had met with little success. The Hankow attack was successful beyond expectations. Eighty-four B-29s were part of a more than 200-plane mission on December 18. In spite of the initial formation dropping its bombs upwind, damage to the docks and warehouses was tremendous. Intelligence estimated that 40 to 50 percent of the target had been destroyed by 38 percent of the bombs. Chennault reported that Hankow had been rendered useless as a military base.

On October 20, 1944, Brig. Gen. Emmett “Rosie” O’Donnell arrived on Saipan to open the headquarters of the 73rd Bombardment Wing, which originally had been intended to be part of Matterhorn but was switched to the Marianas when Saipan fell to the Allies. O’Donnell had been preceded by Brig. Gen. Haywood “Possum” Hansell, who arrived on Saipan on October 12 in the first B-29 to reach the islands. Hansell, a strong advocate of precision bombing, had been involved with the B-29 program from its inception and had previously served as chief of staff of Twentieth Air Force.

Hansell and O’Donnell faced a bomber shortage. The 73rd Wing’s aircraft were strung out across the Pacific all the way back to Kansas and the initially expected arrival of five planes per day had been reduced to two or three. The first mission flown by planes of the new XXI Bomber Command was against the former Japanese supply base at Truk in the Caroline Islands. Truk had originally been selected as the first target for the atomic bomb, but it had been reduced to near-uselessness after falling under attack by Navy carrier-based aircraft and B-24s of the Thirteenth Air Force.

That initial mission was a sortie of 18 B-29s in October. Four aborted, including Hansell’s command ship, thus destroying his chances to fly a combat mission in a B-29. A few days later, his successor, Brig. Gen. Lauris Norstad, invoked a regulation prohibiting the commanding general of a very heavy bombing command from flying over enemy territory.

B-29 Success Rises

Once combat operations against Japan commenced, Hansell and O’Donnell lost their authority for mission planning to Twentieth Air Force in Washington. The first target directive was the destruction of the Japanese aircraft industry, with XX Bomber Command continuing the campaign it had commenced while XXI struck targets out of range of B-29s operating from China. The city of Tokyo itself was not on the list of primary targets, although aircraft factories in outlying areas were. For propaganda effect at home, Twentieth Air Force chose to fly the first mission against the Nakajima Hikoki plant at Mushasino, a Tokyo suburb, which was the number two target on the priority list. The plant was believed to produce more than 30 percent of all Japanese combat aircraft engines, but the main reason it was chosen was so that headlines would read “TOKYO BOMBED!!!” The attack was to be carried out in daylight using precision bombing methods.

Although Hansell submitted plans for an attack in October, the aircraft delivery problem led to a postponement until November. The first B-29 over Tokyo was actually a reconnaissance version, an F-13 piloted by Captain Ralph D. Steakly. Seventeen reconnaissance missions—eight were weather observation flights—were flown over Japan before the first raid. One F-13 was lost to fighter attack on a mission to Nagoya.

Hansell’s plan, code-named San Antonio I, was predicated on intelligence estimates of Japanese fighter strength in the Tokyo area that turned out to be greatly overstated. Estimates ranged from 600 to 1,100 fighters around Tokyo alone, when in reality Japan only had 375 operational fighters to defend the entire country at the time. The attack was initially planned for early November, with Navy carrier strikes preceding the B-29s by five days. But the Navy was preoccupied with operational problems in the Philippine Sea and postponed its operations around Japan entirely.

Hansell decided to go it alone. The raid was set for November 17, but heavy rain and a wind shift led to a postponement. The rains continued for a week, but the morning of November 24 dawned clear, with winds favoring the downhill runway.

General O’Donnell led the formation off the runway with Major Robert K. Morgan, famous as pilot of the B-17 Memphis Belle, in the copilot’s seat. A total of 111 B-29s took off from Saipan, but 17 aborted and six others were unable to drop their bombs. Poor weather over Tokyo and strong jet stream winds made bombing difficult. Only 24 airplanes actually bombed the target. Results were actually better than believed. Japanese records revealed that 48 bombs struck the factory. Damage to the facilities was minor, and less than 150 casualties were reported. Nevertheless, the raid had tremendous psychological value as many of Japan’s civilian leaders realized the war was lost. They began moving production facilities underground, although none of the underground facilities had begun production by the end of the war.

Missions against aircraft industry targets continued into January, but results were poor. Weather conditions between Saipan and Japan presented major problems as cold, arctic air collided with warm Pacific air to produce thunderstorms, a virtual wall that the bombers had to penetrate on their way in and out of the target area. Actual damage to Japanese facilities was minor, although a raid on Nagoya on December 13 did significant damage to the engine factory target.

Twentieth Air Force was pressing for experimental incendiary attacks, a move that Hansell resisted to the detriment of his own future. The success of the Hankow mission on December 18 led Norstad to order a full-scale incendiary attack on Nagoya. Hansell protested the change of focus and did not fly the test mission until January 2. Three days later, Norstad arrived from the United States to inform Hansell that he was being relieved. General Curtis LeMay was brought in from the China-Burma-India Theater to replace him.

Ironically, the last mission flown under Hansell’s command was one of the best precision bombing missions of the entire war. On January 17, a formation of 73 B-29s attacked the Kawasaki plant at Aksahi with 115 tons of high explosive bombs. U.S. intelligence estimated that 38 percent of the buildings were damaged, but actual results were much greater. Japanese records revealed that the plant had been 90 percent destroyed, and Kawasaki decided to shut it down. The successful attack proved Hansell’s theories of daylight precision bombing, but knowledge of the real results came too late to save him from the chopping block.

Heavy Casualties, Inconclusive Results

LeMay’s arrival initially brought few changes. On January 23, he requested permission to attack more lightly defended targets but was advised by Norstad that while he had full latitude for target selection, an incendiary attack on Kobe would be more fruitful. LeMay realized where his bread was buttered and made plans to bomb Kobe on February 4 with an expected 157 planes. The mission was the largest of the war to date, with bombers from two wings participating for the first time. By the time the formation reached the target it had been reduced to just 69 planes. Only 129 had taken off; then aborts and other problems took a heavy toll. The formation dropped 159.2 tons of incendiaries and 13.6 of fragmentation bombs from high altitudes. Some 200 fighter attacks were reported, and one B-29 was lost while 35 suffered damage. Post-strike photos indicated major damage, and the estimates were supported by Japanese records that revealed that some 1,039 buildings had been destroyed or severely damaged. Casualties were moderate, but more than 4,000 people were left homeless.

Following the Kobe mission, the Nakajima plant at Ota, where the company was turning out its new Ki-84 “Frank” fighter, was hit. The Ki-84, a design with high-altitude capabilities, was a threat to the B-29s, which were still flying unescorted. In spite of poor bombing accuracy—only seven incendiaries and 93 high explosive bombs hit the factory—damage was substantial. The handful of incendiaries set fires that destroyed 37 buildings and 74 of the new Ki-84 fighters. Losses had been heavy, with 12 bombers shot down and 29 damaged.

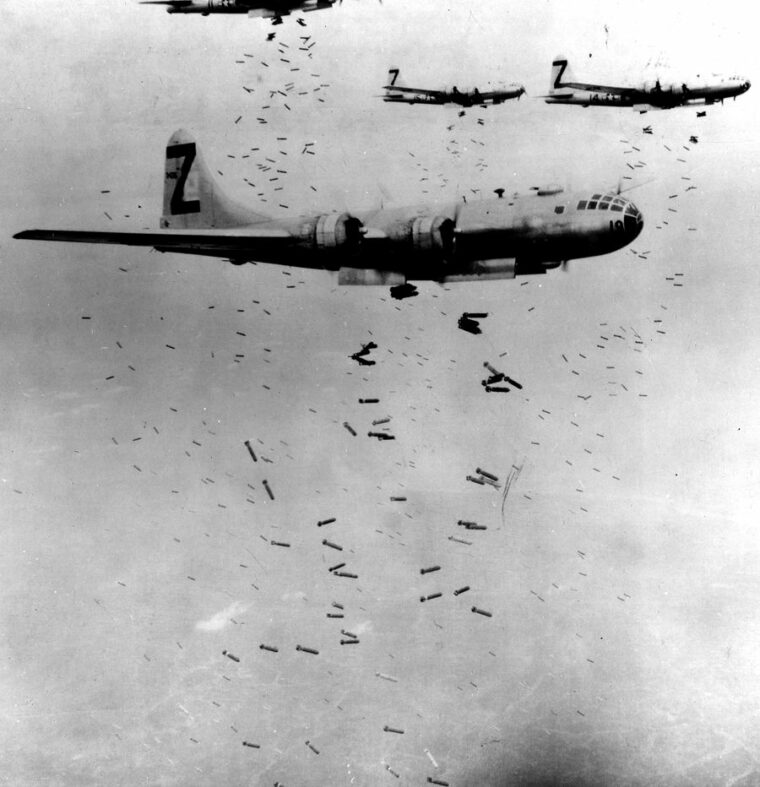

Washington was still interested in a firebombing campaign, and Norstad reminded LeMay that results were still inconclusive. LeMay scheduled a massive firebombing attack on Tokyo for February 25, 1945, with more than 200 bombers participating. Out of 231 B-29s that took off from Saipan, 172 dropped 453.7 tons of incendiaries. Clouds obscured the city, and bombardiers had to release their bombs using radar, but the fires destroyed about one square mile of urban area. Japanese records reported that more than 28,000 buildings were destroyed and thousands died in the flames and from smoke inhalation.

Firestorm in Tokyo: Civilians Become Targets

In early March, LeMay commented to his public information officer, “This outfit is getting a lot of publicity without having accomplished much in bombing results.” That was about to change. Twentieth Air Force had decided that precision bombing was ineffective and that the construction of Japanese cities made them ideal targets for fire-bombing attacks. The change was the result of a major moral shift in the United States. Deliberate attacks on noncombatant civilians had previously been considered immoral. Justification for urban attack was seen in recent Japanese announcements that all men up to age 60 and women to age 45 were part of a civilian mobilization to defend the country against Allied invaders.

LeMay also decided to make a major change in tactics, scheduling future missions at night, at comparatively lower altitudes, reasoning that Japanese antiaircraft defenses were not well organized and that Japanese guns were less accurate than German weapons. In a move to increase payload, he ordered many of the bombers stripped of their machine guns, which had been installed to defend against Japanese fighters.

LeMay developed tactics calling for lead squadrons to mark the target with napalm-filled bombs designed to cause fires to attract the attention of Japanese firefighters. The lead formation would drop its bombs at 100-foot intervals, but the main force, delivering M-69 incendiaries, would drop at half the distance for better concentration with each crew bombing individually. The mission plan called for 334 B-29s, the largest formation to date, with a target date of March 9, 1945. The force was so large that it took three hours for all the airplanes to become airborne.

The bombers encountered the familiar heavy clouds and turbulence on the way to the target, but navigators managed to find their checkpoints using radar. Weather conditions over Tokyo were good, and the pathfinders marked their targets without difficulty. The rest of the formation came in at staggered altitudes between 4,900 and 9,200 feet. An increasing wind fanned the flames of the fires caused by the napalm and incendiaries, producing an expanding firestorm. As the fires spread, bombardiers dropped their bombs on the edge of the fire, thus increasing the size of the conflagration. The target area bordered Tokyo’s main industrial area and included a number of factories, but the main targets were the thousands of homes and feeder plant buildings. Construction in the area was so congested that the fires spread like they were in dry brush, causing flames so high and heat so intense that nothing could escape.

The disaster that befell the citizens of Tokyo that night was one of the worst in human history. The fires spread throughout the city and were only hampered by wide firebreaks, particularly along rivers and canals. Although thousands of people managed to find solace in the waters, the heat was so intense that water in some of the shallower canals literally boiled. Widespread panic increased the death toll as people attempted to run through the flames to escape, only to fall in the intense heat and perish. Radio Tokyo called the attack “slaughter bombing” and compared it to the destruction to Nero’s Rome. The comparison was in error. The damage to Tokyo was far worse. Japanese morale plummeted, and the already rising peace movement in the government gained considerable strength. Resolve among those Japanese who had been willing to fight to the death against invasion began to crumble.

Losses among the B-29s had been high, but the rate was still less than that of previous missions. LeMay’s decision to go in low had been justified. He did, however, decide to arm the bombers once again for future missions in the event Japanese night fighter defenses became more effective. Nicknamed “Old Iron Ass,” LeMay did not give the Japanese any breaks.

By Bombing Alone

On the afternoon of March 11, a force of 313 bombers took off for Nagoya. Some 285 actually got over the target, but the damage was not as great as inflicted on the Tokyo mission. Bombardiers spread their loads over a wider area, and the light winds over the city failed to produce the conflagration that destroyed Tokyo. Smoke was still rising from the Nagoya attack as the first of 301 bombers took off for a mission against Osaka, which had yet to be hit by American bombs. Aborts left 274 B-29s to find a target obscured by 80 percent cloud cover. The necessity of using radar actually led to a closer concentration of bombs and a resulting conflagration that wiped out eight square miles of the heart of the city, including the main commercial and industrial areas. The Nagoya raid proved that the Tokyo mission had been no fluke.

LeMay flew five fire-bombing missions before the kamikaze crisis during the invasion of Okinawa led to a diversion of the B-29s to attacks against the airfields on Kyushu from which they originated. The success of incendiary missions led him to conclude that while the official Twentieth Air Force mission was to prepare the Home Islands for an invasion, it was possible to force Japan to surrender by bombing alone.

On April 25, LeMay wrote a letter to Norstad informing him of his belief. LeMay was not alone in his conclusion. Two weeks before LeMay wrote his letter, Twentieth Air Force Director of Plans Colonel Cecil Combs recommended that fire-bombing missions be stepped up immediately after the surrender of Germany to force Japan to do likewise. Former ambassador to Japan Joseph C. Grew believed that Japan was on the verge of surrender and advised President Harry Truman of his belief. Numerous other high-ranking officers, including MacArthur and his subordinate, General Kenney, shared the belief.

The strategic bombing campaign was placed on hold for almost a month as 75 percent of XXI Bomber Command missions were directed in tactical attacks. Most of the strategic missions during the period were high-altitude precision missions with high explosives, but LeMay managed to get in a few fire-bombing raids, including two against targets around Tokyo Bay. By the end of May, LeMay had sufficient resources to mount raids of more than 500 planes, and by mid-June the cities ringing Tokyo Bay had been burned to the ground. June 15 concluded Phase I of LeMay’s Urban Bombing Campaign, and the results were spectacular. Japan’s six largest cities had been bombed to ruins, and the country’s industrial base was in shambles. Casualties among the Japanese population were well over a million, with the dead numbered in the hundreds of thousands.

Bombed into Submission

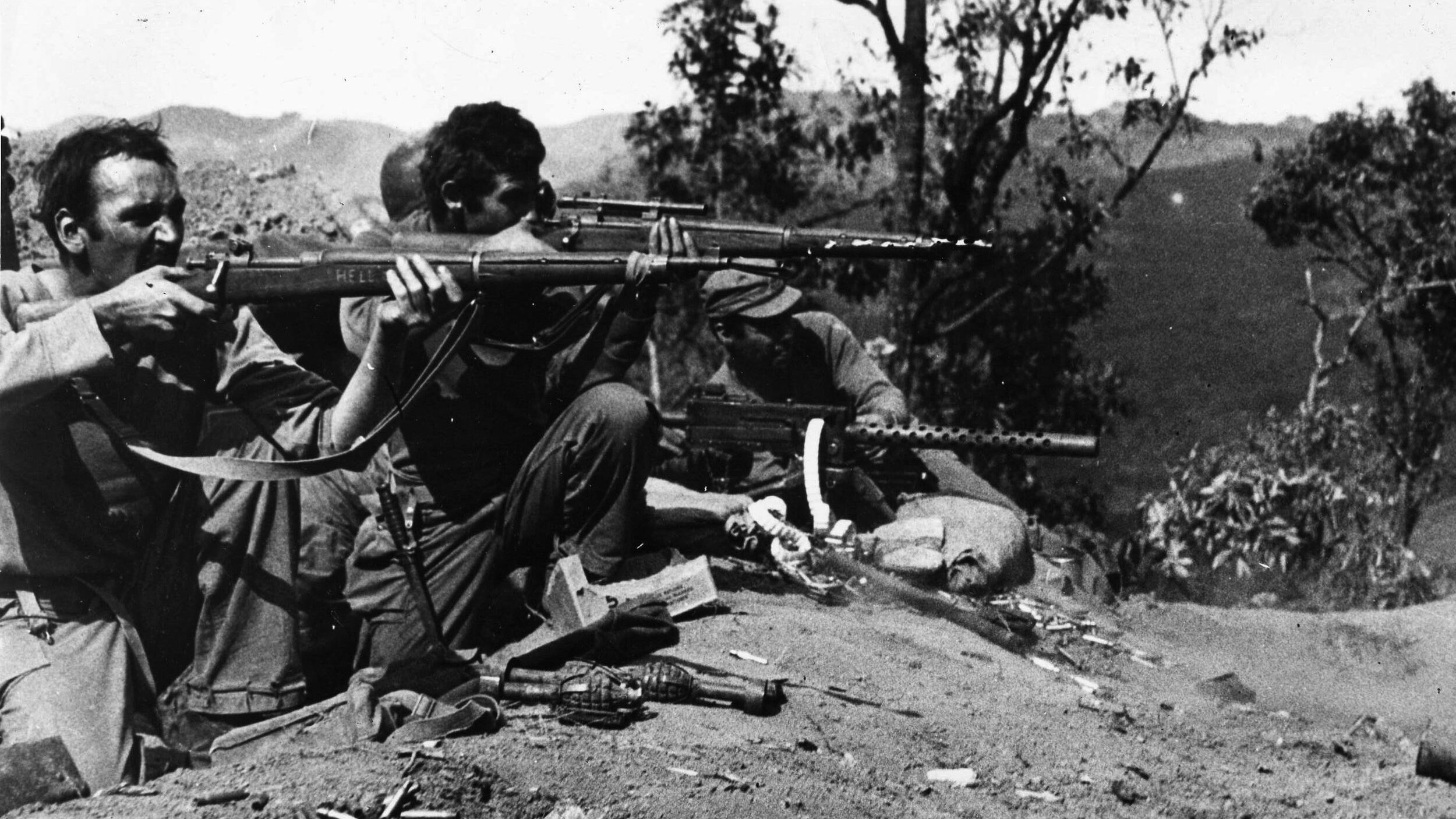

The capture of Okinawa brought Fifth and Seventh Air Force B-24s within range of targets in Japan, and the Liberators joined the Superfortresses in the fire raids against Japanese cities while North American B-25 Mitchell bombers struck targets on Kyushu in preparation for the upcoming invasion scheduled for November 1. Navy aircraft carriers joined the attack on Japan along with Army fighter-bombers operating from Iwo Jima and the Ryukus. The Japanese people were being subjected to the most intense aerial bombardment in history, and their resolve was beginning to wear down.

President Harry Truman issued the Potsdam Declaration on July 26, 1945, calling for the unconditional surrender of Japan, and many in the Japanese government wanted to accept it. Three members of the cabinet objected on the basis that the Declaration placed the fate of the emperor in question and branded members of the country’s former government as war criminals (the Japanese government had gone through two reorganizations since the invasion of Saipan).

American bombers began dropping leaflets warning the Japanese that their entire population was in danger of starvation, and it was hardly an empty threat for a country that was largely dependent on food imports. The fact that the Japanese were losing their resolve became apparent on August 4, when Fifth Air Force pilots operating over Kyushu came back to report that white flags were being waved throughout the island. Two days later, the first atomic bomb exploded in the sky over Hiroshima.

Although popular myth relates that Japan surrendered because of the detonation of the atomic bombs, in reality the new weapons had little effect on an already demoralized population. This was partially due to the distances from the target cities to Tokyo. Most Japanese were only aware that a terrible new weapon had been detonated—few realized its importance. When President Truman promised a rain of destruction from the skies on Japan, he was addressing a country that had already been bombed into near oblivion. On August 14, the emperor addressed the Japanese people for the first time in history, telling them that the country was surrendering.

While the author is quite correct about the morale and condition of the Japanese people, and probably most of the fighting military, the more militant staff officers and commandeers were ready to fight to the last man, woman and child. There was even an attempted coup and and several assassinations mounted in an attempt to continue the fight. It was indeed Hirohito’s decision to end the war, citing in his message to the people “a new and terrible weapon”. There is no way of knowing how the war would have ended without the emperor’s decision, but we do know the events leading to that decision.

Agree with you. It required something on a scale truly never seen before – one bomb wrecking an entire city – to get the emperor to decide to end the war. Read where the Japanese people were war-weary, but keep in mind Germany was bombed much more heavily for rather longer and the people kept working and producing for the German war effort until we and the Allies physically conquered the country. Also suggest large areas of Japan proper were never bombed, just certain cities.

“The ultimate decision on deployment of the B-29s was based largely on political considerations, including appeasing President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s near-obsession with mounting an aerial bombardment campaign against Japan at the earliest opportunity. The liberal president was up for reelection to an unprecedented third term in 1944 and faced strong opposition from conservatives. The commencement of B-29 raids on Japan would boost his political stock.”

“Roosevelt won the 1944 election by a comfortable margin with 53.4% of the popular vote and 432 out of the 531 electoral votes.”

Maybe the author should stick to military matters instead of letting his personal political feelings bleed into the article. Everyone should have been obsessed with bombing Japan into submission regardless of political ideology. It proved to be the correct path, as it directly led to Japan’s surrender. I suggest that if you’re writing about politicians, just describe them as what party affiliation they belong to. As we can see with today’s politics, conservatives aren’t conservative and liberals aren’t liberals. And as we also know, the ’44 election was a landslide victory for FDR. The opposition was fairly weak, and would lose again in ’48 to Truman, who was more conservative than today’s version. Thanks.