by Roy Morris Jr.

In the winter of 1893, a struggling young writer named Stephen Crane dropped by the art studio of his painter friend Corwin Linson at the corner of Broadway and 30th Street in New York City. Crane, a native of New Jersey, had grown up in Port Jervis in upstate New York, the son of a widowed temperance crusader and a Methodist minister father who died when Crane was six. Now 22, Crane had recently written his first novel, Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, a scandalous account of a young woman’s descent into poverty, prostitution, and death. [text_ad]

But the book, despite positive reviews from such leading critics as William Dean Howells, had sold few copies, and its almost literally starving author was reduced to burning copies of the book in the fireplace of his Bowery apartment for warmth. Barely scraping by as a freelance journalist for various New York newspapers, Crane joked mordantly, “I’d sell my steps to the grave at ten cents per foot.”

Civil War Inspiration

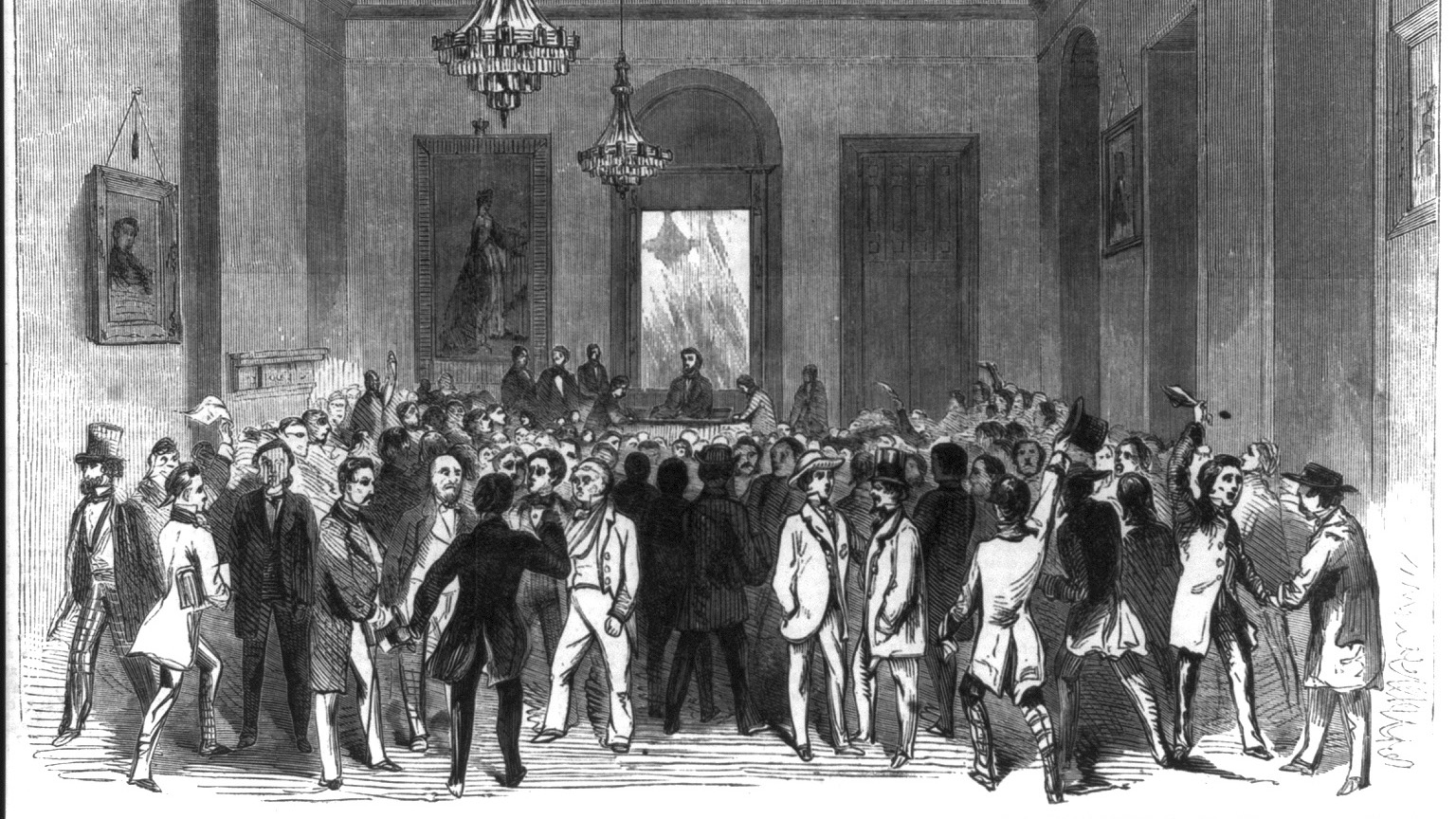

Linson was doing better financially, supporting himself as a magazine illustrator. As an offshoot of his work he avidly collected back issues of the leading journals of the day. On this early March afternoon, while Linson sketched at his easel, Crane’s attention turned to a stack of Century magazines lying scattered on the floor. The magazine featured a popular, long-running series, “Battles and Leaders of the Civil War.” Crane had long been fascinated by the subject of war; his ancestors had been heroes during the American Revolution. He had been entertaining thoughts of writing a war story of his own, “a potboiler, something that would take the boarding school element.” He picked up an issue of the magazine—and soon after American literature would never be the same.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments