By Roy Morris Jr.

Men have been reporting their wars almost as long as they have fighting them. The first prehistoric cave drawings depicted hunters bringing down wild animals, and spoken accounts of battles, large and small, formed the starting point for the oral tradition of history. All native cultures have mythologized warfare and glorified warriors, often giving them divine status. The Greek poet Homer’s epic works, The Odyssey and The Iliad, recounted the Trojan War and its aftermath, and The Song of Roland told of the Moorish invasion of Europe. The greatest of all writers, William Shakespeare, memorialized England’s dynastic wars in his plays, and John Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost depicted the armies of God and the armies of Satan arranged “in dubious battle on the plains of heaven.” Even Jesus, the ultimate peace-giver, was shown in the Gospels driving the moneylenders from the temple at the point of a whip.

The Early Beginnings of the Modern War Correspondent

The profession of war correspondent, however, is a comparatively new development in human history. Scholars have long debated the identity of the first such correspondent. Candidates as varied and ancient as the Greek historian Thucydides, who wrote about the Peloponnesian War in 424 bc, and Roman emperor Julius Caesar, who described his conquest of Gaul in 55 bc, have been advanced—although in both cases, the authors’ chronicles were written several years after the wars themselves. William Watts, the probable author of a 17th-century account of Swedish King Gustavus Adolphus’s campaigns during the Thirty Years’ War, is another frequently mentioned candidate. But Watts’s anonymous reports, published in a pamphlet entitled the Swedish Intelligencer, came several months after the events themselves, and Watts composed them in London, far from the scene of the European fighting.

Two early 19th-century newspaper reporters, Henry Crabb Robinson of the London Times and Charles Lewis Gruneison of the London Morning Post, have been put forward as early war correspondents. Robinson, a barrister by profession, accepted an offer from the Times to relocate to Altona, Germany, in 1807 and send back reports of French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte’s 1807 campaign. With the help of a friendly German editor, Robinson poured over public documents and mingled with the social elite to send back accounts, mostly rumors, of Napoleon’s progress on the continent. Datelined “From the Banks of the Elbe,” Robinson’s articles added little real detail to the hearsay gossip, and he made no attempt to reach the battlefield, reporting on the Battle of Friedland, for example, six days after it occurred.

The next year, Robinson headed south to report on the Spanish revolution “from the shores of the Bay of Biscay.” Again he arranged with a local editor to use already published news reports as the basis for his articles, and he was not even aware that the Battle of Corunna had taken place until he went to dinner one night and found the dining hall deserted. “Have you not heard, sir?” a waiter asked. “The French are come; they are fighting.” Robinson walked down to the harbor and climbed aboard a ship, where he reported hearing the sound of cannons “come from the hills about three miles from Corunna.” He later observed English wounded and French prisoners brought into the city, but he missed completely the death of English commander Sir John Moore in the battle.

Gruneison also went to Spain, three decades later, to report on the ongoing Carlist revolt. More industrious than Robinson, Gruneison accompanied the British Legion and attached himself to the headquarters of King Don Carlos. Although a music critic by training, Gruneison proved to be an industrious reporter, going to the scene of the Battle of Villar de los Navarros and several smaller actions. After one encounter, he personally managed to prevent the massacre of prisoners by prevailing on the Spanish commander as a fellow Mason to spare the men’s lives. After the Battle of Retuerta, Gruneison was arrested on suspicion of being a spy, and narrowly missed being executed. Returning to England, he later served as the newspaper’s Paris correspondent, organizing a carrier pigeon service between the French capital and London. He saw no further fighting.

John Bell: the First War Correspondent

Perhaps the best candidate for the honor of first war correspondent is London Oracle reporter John Bell, who reported on the Duke of York’s European campaign in 1794. Bell, who owned the newspaper, embarked for Flanders in April of that year to report on the British expeditionary force that had landed in the Netherlands to cooperate with the Allies against the revolutionary French. Announcing his attention to “establish a chain of regular correspondents with every part of the Allied army, and to take every possible method of obtaining French papers with more regularity and dispatch than has hitherto been practicable,” Bell described his motives in words that could have been written by professional war correspondents a century later: “As I shall, for some time, be in the very neighborhood of the contending armies, it is my intention to send you a regular and faithful diary of whatever passes worthy the attention of your readers. I shall write frequently in the field, or under the first hedge that affords me safe retreat; and therefore must be satisfied with facts, without ornament or exaggerated coloring, which on such occasions is too frequently adopted in the diurnal publications.”

In contrast to Robinson, Bell eschewed the safety of cities for the authenticity of the battlefront, witnessing one British cannonade from a nearby tower and finding himself in the midst of the action during the Battle of Courtray, on May 17-18, 1794. His vivid account of the battle, written on the field, described “the confusion of unhappy defeat” and pictured the soldiers staggering away “with fatigue almost insupportable.” Bell’s scoop of the British defeat at Courtray preceded the official announcement by two days, and he later predicted the imminent fall of Ypres, warning that “if Ypres falls, I think all of this part of the country is lost.”

In some ways, Bell was the first celebrity war correspondent. His departure for the front was widely publicized, and in an era when most newspaper columns were uncredited, Bell’s name was prominently featured above his battle reports and often at the end of the articles as well. The Oracle itself was quick to trumpet the correspondent’s scoops, crowing: “The other newspapers will, as usual, copy our intelligence tomorrow.” The British government complained predictably about Bell’s implicit criticism of its efforts, and rival newspapers criticized his “contradictory and false rumors” as the work of a “vagabond Jacobin.” By the end of the year, Bell was forced to sell the Oracle to settle the debts he had run up while covering the war.

The Growth of the American Press in War

In the United States, the meteoric rise of newspapers had helped the patriots win the Revolutionary War by keeping the colonists abreast of events in the field and printing morale-boosting broadsides and sloganeering pamphlets. At the time, there were no active correspondents covering the fighting, although Massachusetts Spy editor Isaiah Thomas, a member of the Sons of the Liberty, managed to print his own eyewitness account of the first clash between English and American forces at Lexington, Mass., in April 1775. The subsequent War of 1812 saw comparatively little on-scene reporting, and the most famous firsthand account from the battlefield was not a journalist’s prose report, but rather Baltimore attorney Francis Scott Key’s spirited poem on the defense of Fort McHenry, “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

When war broke out between the United States and Mexico in 1846, an enterprising New Orleans journalist, George Wilkins Kendall, was quick to intuit the circulation-growing opportunities of the conflict. As publisher of the Picayune in New Orleans, the closest major American city to Mexico, Kendall was in the best position to monitor the war. Hurrying to the headquarters of General Zachary Taylor at Matamoros, Kendall set up a field office, recruited a staff of able correspondents, and arranged for his dispatches to be carried by horseback to Veracruz, where they were transferred to a fleet of fast boats and taken back to New Orleans. To maximize time, Kendall outfitted the boats with typesetting equipment and a stable of compositors. By the time the boats docked, the stories were ready for the presses.

The rules of engagement—or nonengagement—for correspondents had not yet been formulated, and Kendall and other journalists often went into battle alongside the American troops. While sending back newspaper reports of the fighting, Kendall also served as an aide-de-camp to General Taylor, captured a Mexican cavalry flag, and suffered a bullet wound to the knee. By war’s end, he was answering to the honorary rank of “Major.” Another journalist, New Orleans Delta reporter James L. Freaner, earned the nickname “Mustang” after he killed a Mexican officer and appropriated his horse.

By all accounts, Picayune reporter Christopher Haile, a graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, was the most accurate and accomplished correspondent in the field. He covered the fighting at Resaca de Palma, Palo Alto, and Monterrey before being commissioned a first lieutenant in the infantry during the siege of Veracruz. Two former Picayune staff members, John Peoples and Charles Callahan, set up their own newspaper in camp, which they called the Veracruz Eagle. When the action moved on to Mexico City, they followed General Winfield Scott’s army and started a second camp newspaper, the American Star. Besides accounts of battles, the quasi-official publications also carried articles on promotions, transfers, courts-martial and executions, along with more welcome news from the home front. The ever-enterprising Kendall simply enclosed issues of the Star along with his letters from the front. By war’s end, no fewer than 26 field newspapers were being published on Mexican soil.

Five years after the Mexican War ended, another major war broke out in Europe, the first since the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. The Crimean War, involving Great Britain, France, and Russia, was fought primarily on the desolate Crimean Peninsula of southwestern Russia, bordering the Black Sea. The origins of the war were obscure, involving a squabble between Christian and Orthodox monks over control of holy shrines in Jerusalem, but the larger stakes involved long-standing Russian ambitions to gain access to the Mediterranean through the Turkish-controlled Bosporus Strait. Great Britain and France, as allies of the Turks, were not about to let that happen.

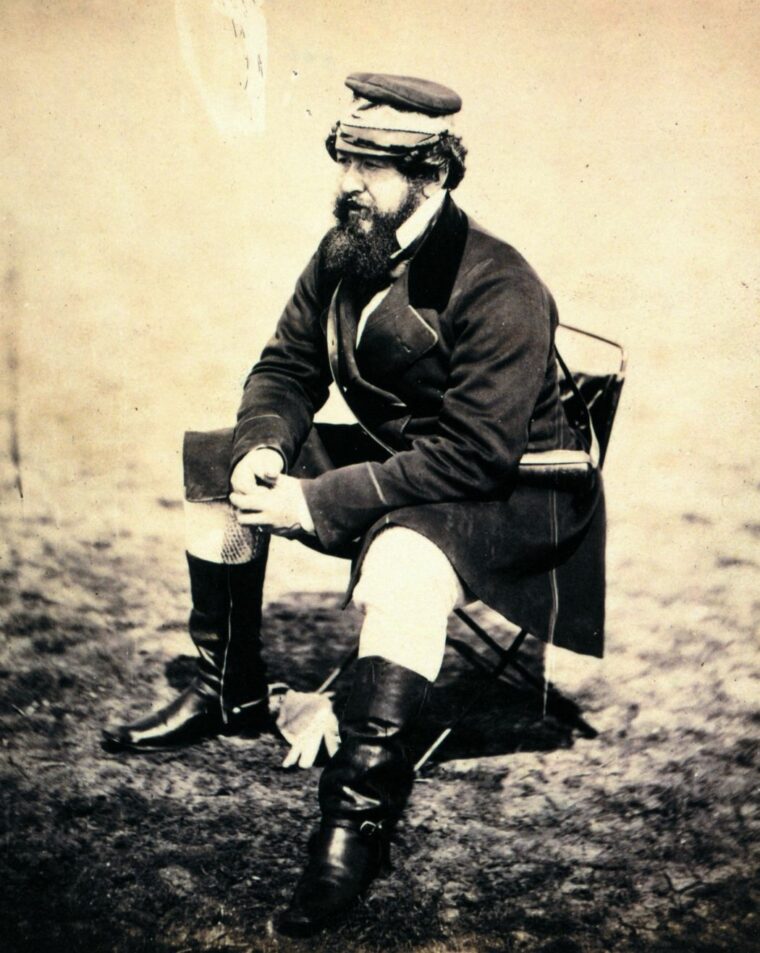

The World Famous William Howard Russell

The ensuing war saw the emergence of the first world-famous war correspondent, London Times reporter William Howard Russell. The Irish-born Russell, who had grown up a burly street fighter in Dublin and Liverpool, was an inspired choice. Not only was he personally fearless, but he was absolutely committed to telling the truth, which he dubbed “Miss Verity,” regardless of whom he offended. Dispatched first to Malta by Times editor John Delane, who promised the initially reluctant Russell that he would be “home by Easter,” the 33-year-old reporter arrived in the Crimea in the spring of 1854. He would not set foot on British soil for another two years.

Russell wasted little time alienating the powers that be, including the British commander Lord Raglan, who ordered his officers not to talk to the snoopy intruder. From the beginning, Russell was outraged at the lack of planning evinced by the British Army, whose officers often seemed more concerned with enforcing a strict gentleman’s dress code than they were with providing for the needs of their men. “The management is infamous,” Russell wrote to Delane, “and the contrast offered by our proceedings to the conduct of the French most painful. Can you believe it—the sick have not a bed to lie upon? They are landed and thrown into a rickety house without a chair or table in it. While these things are going on, Sir George Brown only seems anxious about the men being clean-shaved, their necks well stiffened and waist belts tight. He insists on officers and men being in full rig; no loose coats, jackets, etc.” Russell wondered, “Am I to tell these things, or hold my tongue?” To his credit, Delane instructed his reporter to tell the truth, and began circulating Russell’s private letters to his friends in Parliament, initiating a low grumble of discontent among back-benchers at the government’s conduct of the war.

Raglan’s junior officers harassed Russell, cutting down his tent whenever his back was turned and refusing to issue him rations. Higher ranking officers denied his requests to join their camps. In the end, this worked to Russell’s favor, since he was forced to get his information from the soldiers themselves, writing down their accounts of the Battle of the Alma on an improvised table made from a wooden plank laid across two water casks. His next account, following the Battle of Balaclava, created a sensation. Climbing a high ridge overlooking the fortified port of Sevastopol, Russell watched the Russian Army attempt to break the siege by attacking the Turkish line. The British rushed reinforcements into the area, including the Light Brigade of Cavalry, whose frequently drunk commander, Lord Cardigan, was ordered to stop the Russians from carrying away some Turkish cannons. Cardigan interpreted the vague order to mean instead that he was supposed to charge the bristling rank of Russian guns.

Russell’s account of the ensuing charge made him—and the Light Brigade—famous. “Surely this handful of men are not going to charge an army in position?” he wrote. “Alas! It was but too true—their desperate valor knew no bounds, and far indeed was it removed from its so-called better part—discretion. At a distance of 1200 yards the whole line of the enemy belched forth, from thirty iron mouths, a flood of smoke and flame, through which hissed the deadly balls. Their flight was marked by instant gaps in our ranks, by dead men and horses, by steeds flying wounded or riderless across the plain. With a cheer that was many a noble fellow’s death-cry, they flew into the smoke of the batteries, but ere they were lost from view the plain was strewed with their bodies and with the carcasses of horses. At thirty-five minutes past eleven [the charge had begun 25 minutes earlier] not a British soldier, except the dead and dying, was left in front of those bloody Muscovite guns.”

Russell’s account of the charge of the Light Brigade, which was quickly followed by British poet-laureate Alfred Lord Tennyson’s famous poem of the same name, stirred emotions on the home front and led briefly to an upturn in public support for the war. In the meantime, however, Russell continued reporting the dire conditions of the common soldiers, whom he termed “miserable, washed-out, worn-out spiritless wretches.” The government denied that anything was wrong and attempted to censor the Times’ dispatches, claiming that they were aiding the enemy. Queen Victoria’s stiff-necked consort, Prince Albert, got into the fray, complaining loudly and openly about “that detestable Times.” A friendly photographer, Roger Fenton, was dispatched to the Crimea to take morale-boosting photographs of well-ordered camps, teeming harbors, smiling officers, and happy allies sharing a smoke and a drink. Fenton managed to lie by omission, and even his most famous photograph, “The Valley of the Shadow of Death,” was false, purporting to show the valley in which the Light Brigade had charged, but depicting instead a meaningless gully littered with spent cannonballs.

By the time Fenton’s photographs had been displayed to a credulous public, it was too late to save the discredited government of Prime Minister Lord Aberdeen. His replacement, Lord Palmerston, invited Russell to lunch after the correspondent returned to England in 1856, and startled the newsman by asking him, in all seriousness, what he would do if he were commander-in-chief. Russell, finding himself much sought-after, wrote a book about his Crimean War experiences and set out on a well-attended lecture tour. He was later knighted by Queen Victoria’s successor, King Edward VII, who told him avuncularly, “Don’t kneel, Billy, just stoop.”

Reporters of the American Civil War

Russell’s fame preceded him to America, where he arrived just in time to witness the opening battle of the Civil War. After chatting with new president Abraham Lincoln (who supposedly told him that the Times was the greatest natural force in the world “except, perhaps, for the Mississippi River”), Russell dined with Secretary of State William Seward, who sought his favor in winning English support for the North. On July 16, 1861, Russell headed for Manassas, Va., where a major battle was taking place for control of a key railroad junction. Three miles from the battlefield, he was caught up in a panicky backwash of Union soldiers, civilians, and government officials who were fleeing from phantom hordes of Confederates. The North had lost the battle. One fear-crazed soldier pulled a pistol on Russell and attempted to shoot him—fortunately for the correspondent, the gun failed to fire. When his subsequent account of the battle appeared in the Times, angry Northerners accused Russell of exaggerating the panic. Some said he had lied, others said he had been drunk under a tree at the time of the battle. Denied permission to travel with the Union Army, Russell returned to England in disgust. He would later cover the Austro-Prussian War, the Franco-Prussian War, the Paris Commune, and the Zulu War, but he would not return to America for the remainder of the Civil War.

It was just as well. There were more than enough Americans on hand to cover the war without Russell’s help. Some 500 journalists attached themselves to the Union Army during the course of the war, and another 100 reported the war from the Southern side. Never before had a war been so thoroughly written about, and the crush of reporters did not always sit well with commanders in the field. Union general William Tecumseh Sherman’s feud with the press started early and lasted late. It began in the fall of 1861, when he succeeded Brig. Gen. Robert Anderson as commander of the Department of the Cumberland, whose responsibility it was to safeguard President Lincoln’s home state of Kentucky. When Sherman met with Secretary of War Simon Cameron and requested another 60,000 troops to hold the state, a reporter for the New York Tribune, unknown to Sherman, was on hand taking notes. His subsequent report characterized the general as “insane,” “stark mad,” and displaying “strange conduct,” and Sherman was immediately removed from command and nearly sacked from the Army.

Understandably bitter about the press’s role in his removal, Sherman acquired a lifelong aversion to journalists, whom he termed “a dirty set of scribblers who have the impudence of Satan.” He soon crossed swords—or pens—with one such scribbler, New York Herald correspondent Thomas W. Knox, nicknamed “Elephant” for his large size and even larger ego. During the initial stages of the Vicksburg campaign, Knox reported that Sherman was “so exceedingly erratic that the discussion of a twelve month ago with respect to his sanity was revived with much earnestness. Insanity and inefficiency have brought their result.” When Sherman read the article, he had Knox arrested and brought before him. Knox was unrepentant. “I have no feeling against you personally,” he told the enraged general, “but you are regarded as the enemy of our set, and we must in self-defense write you down.” Sherman wanted to court-martial Knox for violating Army regulations requiring all news reports to be approved by the commanding general in advance, but settled instead for kicking him out of camp. Ironically, Sherman’s action may have saved Knox’s life. Not long after his banishment, three fellow reporters were blown out of the water while attempting to run the Vicksburg batteries. Knox always believed he would have been aboard the ill-fated boat as well. Sherman, told that the shelling had killed three reporters, responded, “Good! Now we’ll have news from hell before breakfast.”

General Grant and the Press

Not all generals had such an adversarial relationship with the press. Indeed, Union General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant owed his career to two friendly journalists. The first, Welsh reporter Sylvanus Cadwallader performed his greatest service to Grant by not writing a story about the general’s drunken antics aboard the steamship Diligent in June 1863. Cadwallader was the only journalist to accompany Grant on a two-day inspection tour of Union positions around Vicksburg. “I was not long in perceiving that Grant had been drinking, and that he was still keeping it up,” Cadwallader admitted many years later. “He made several trips to the barroom of the boat, and became stupid in speech and staggering in gait.” Grant, who had a history of binge drinking when under stress, drank heavily throughout the trip, and Cadwallader acted more as nursemaid than reporter, finally getting the general to lie down and sleep it off. Had he reported Grant’s actions accurately, it is highly likely that Grant would have been relieved of command before Vicksburg fell and his reputation soured.

Grant was also well served by another New York journalist, former Tribune editor Charles A. Dana, who like Cadwallader first made his acquaintance at Vicksburg. Dana had traded in his reporter’s pen for a governmental post as assistant secretary of war. His job was to report on Grant’s conduct to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, who had been hearing disturbing rumors about the general. Grant, displaying the first signs of the surprising political skills that would later carry him to the White House, cultivated Dana’s friendship and treated him as a military equal. Dana, in turn, sent back glowing reports on Grant’s leadership skills, cementing his hold on command. Six months later, performing a similar duty in Tennessee, Dana gave a less receptive Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans disastrous marks for mishandling the Battle of Chickamauga, and sent Lincoln and Stanton entirely misleading reports about Rosecrans’s alleged plans to abandon Chattanooga. When Rosecrans was removed, Dana humbly suggested that Grant be given the post, and his rapid success in breaking the Confederate siege (using Rosecrans’s own plans) led to Grant’s transfer to Virginia, where he ultimately would defeat Robert E. Lee and win the war.

George Smalley’s Ride Through Antietam

The single most impressive scoop of the war was made by New York Tribune reporter George Smalley at the Battle of Antietam in September 1862. Smalley spent much of the battle—the bloodiest single day in American history—acting as an unofficial messenger for Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, who commanded one of the Union corps at Antietam. Riding from one end of the battlefield to the other, Smalley had two horses shot from under him and Rebel shrapnel tore his coat. After Hooker was wounded, Smalley withdrew to a small farmhouse crowded with other wounded soldiers, where he began writing a firsthand account of the battle, which he termed “the greatest fight since Waterloo.”

Commandeering another horse, he set out for Frederick, where he dictated several pages of descriptive reporting to a sleepy telegraph operator before jumping on a train bound for Baltimore. Talking his way onto a military train, Smalley made it to New York City the next morning, writing all the way. The Tribune brought out a breakfast extra edition containing six columns of Smalley’s report, the first news the North had of its first significant victory in the war. Fourteen hundred other newspapers picked up the story, and New York Evening Post editor William Cullen Bryant called it “a truly admirable account, which ranks for clearness, animation and apparent accuracy with the best battle pieces in literature, and far excels anything written by Crimean Russell.”

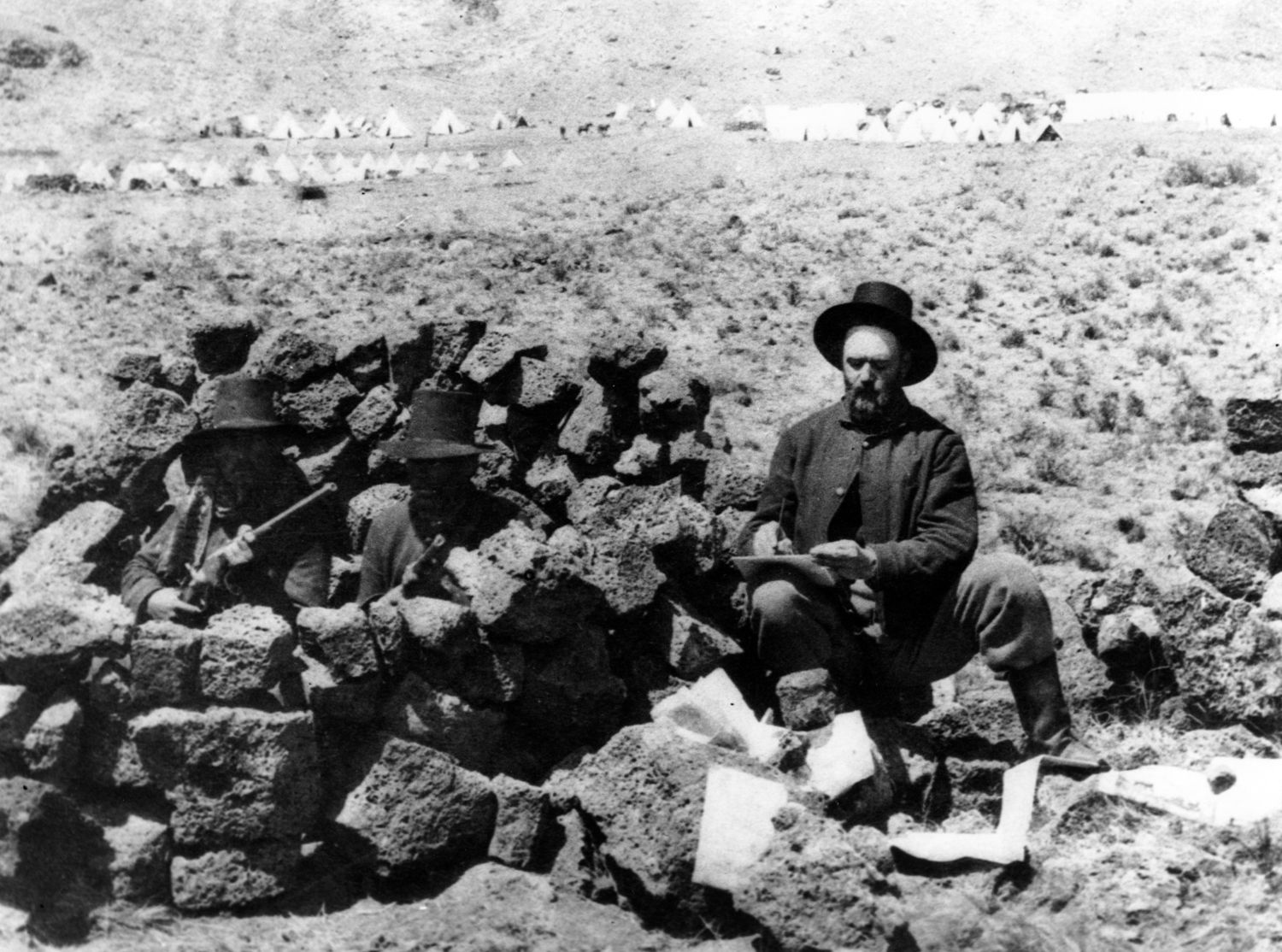

A Journalist’s Demise at Little Bighorn

The Army’s various campaigns against the Plains Indians following the Civil War received a good deal of coverage in the newspapers of the day, but most of it was eastern-based editorializing that was far removed from the widely scattered encounters on the frontier. One luckless newsman, however, 40-year-old Mark Kellogg of the Bismarck Tribune, did manage to get himself killed alongside Colonel George Armstrong Custer and the rest of the 7th Cavalry at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in June 1876. Kellogg, a part-time journalist and law clerk, was a last-minute replacement for Tribune editor Clement A. Lounsberry, who was scheduled to accompany Custer on the expedition, but had to cancel when his wife became ill. Kellogg, an inveterate Indian hater who signed his dispatches “Frontier,” eagerly took his place. His last report to Lounsberry concluded: “We leave the Rosebud [Creek] tomorrow, and by the time this reaches you we will have met and fought the red devils, with what results remains to be seen. I go with Custer and will be at the death.” He was. Months later, a scouting party came upon Kellogg’s decomposing remains in a ravine overlooking the Custer battlefield. He had been scalped, and one ear had been lopped off. He was identified by his curiously patched boots.

Two Views of the Franco-Prussian War

In Europe, a new generation of correspondents followed in the footsteps of William Howard Russell. One of the most prominent was Archibald Forbes, a German-speaking Scotsman who recently had resigned his commission after serving five years in the British Royal Dragoons. When the Franco-Prussian War broke out in 1870, Forbes chose to cover the German side of the war for the London Daily News. His first dispatch, following the Battle of Gravelotte in August 1870, was a classic of firsthand observation, depicting Prussian king Wilhelm I and his chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, nervously waiting for news of the outcome: “The old King sat, with his back against a wall, on a ladder, one end of which rested on a broken gun-carriage, the other on a dead horse. Bismarck, with an elaborate assumption of coolness which his restlessness belied, made pretence to be reading letters. The roll of the close battle swelled and deepened till the very ground trembled beneath us. The hoofs of a galloping horse rattled on the causeway. A moment later [General Helmuth von] Moltke, his face for once quivering with emotion, sprang from the saddle, and running to the King, cried out, ‘It is good for us; we have carried the position, and the victory is with your Majesty!’ The King started to his feet with a fervent ‘God be thanked!’ and then burst into tears. Bismarck, with a great sigh of relief, crushed his letter in the hollow of his hand.”

Thanks to his closeness to the German high command, Forbes was one of only two journalists—a Dutch correspondent was the other—to witness French emperor Napoleon III’s abject surrender to Bismarck at an isolated weaver’s cottage following the climactic Battle of Sedan in September 1870. He further traded on his unexcelled access by persuading German commanders to give him advance details of their plans to bombard Paris. Armed with the plans, Forbes telegraphed a before-the-fact account of the bombardment to the Daily News, which preset the report in type. As soon as he heard the first gun go off, Forbes instructed a waiting telegraph operator to signal “Go ahead,” and the newspaper rushed his scoop into print two full days before his competitors.

A second resourceful Daily News reporter in Paris that fall was an Englishman with a decidedly French-sounding name. Unlike Forbes, Henry Labouchere was trapped inside the besieged city, where he entertained readers with a lively account of his gastronomical vicissitudes. Signing himself “Besieged Resident,” Labouchere sent his articles to London by balloon—a colorful means of transport that gave added zest to his reporting. “I confess I am not one of those persons who snuff up the battle from afar and feel an irresistible desire to rush into the middle of it,” Labouchere admitted. “To be knocked on the head by a shell merely to gratify one’s curiosity appears to me to be utmost height of absurdity.” Instead, the urbane reporter focused on his fellow Parisians’ inventive means of cooking their less than haute cuisine meals, which included eating all the animals in the Paris Zoo and concocting gruesome stews composed variously of dogs, cats, donkeys, squirrels, and something called all too graphically “salami of rat.”

The Press Drives the Russo-Turkish War

One of Forbes’s associates at the Daily News, the grandly named, American-born Januarius Aloysius MacGahan, made journalism history later that decade with his impassioned reports from the far eastern stretches of Central Europe. MacGahan first attracted attention with his daring coverage of a Russian expedition against the Muslim city of Khiva in the spring of 1873. Writing for the New York Herald, MacGahan described an attack on the Muslims by Cossack cavalry: “Down the little descent we plunge, our horses sinking to their knees in the yielding sand, and across the plain we sweep like a tornado. Then there are shouts and cries, a scattering discharge of firearms, and our lines are broken by the abandoned carts, and our progress impeded by the cattle and sheep that are running wildly about over the plain. It is a scene of the wildest confusion. I halt a moment to look around me. Here is a Turcoman lying in the sand, with a bullet through his head; a little farther a Cossack stretched out on the ground, with a horrible saber cut on the face; then two women, with three or four children, sitting down in the sand, crying and sobbing piteously, and begging for their lives.”

When fighting erupted between the Ottoman Turks and Bulgarians in 1876, the Daily News hired MacGahan to cover the story. He traveled to the Balkans, where he found Turkish irregulars, called Bashi-Bazouks, engaged in a systematic reign of terror against the rebellious Bulgarians. Scores of villages had been burned to the ground, and thousands of residents, including some Germans, Greeks, and Armenians, had been slaughtered. In the town of Panagurishte, MacGahan witnessed bearded Turks plucking infants out of their cradles with bayonets and tossing them into the air before spitting them again on their blades. Women and young girls were raped and murdered in the streets. “The procedure seems to have been as follows,” wrote MacGahan. “They would seize a woman, strip her carefully to her chemise, laying aside any ornaments and jewels she might have about her. Then as many of them as cared would violate her, and the last man would kill her or not as the humor took him.”

In one churchyard, MacGahan came upon the corpses of some 3,000 murdered villagers: “It was a fearful sight—a sight to haunt one through life. There were little curly heads there in that festering mass, crushed down by heavy stones; little feet not as long as your finger on which the flesh was dried hard; little baby hands stretched out as if for help; babes that had died wondering at the bright gleam of sabers and the red hands of the fierce-eyed men who wielded them; children who had died shrinking with fright and terror; mothers who died trying to shield their little ones with their own weak bodies, all lying there together festering in one horrid mass.”

MacGahan’s impassioned reporting led Russia to declare war on Turkey in Bulgaria’s behalf. The subsequent war lasted for 11 months and ended with a Russian victory and the independence of Bulgaria from Turkish rule. MacGahan, weakened by a fall from a horse and other injuries, covered the war from the top of a gun carriage, sending his final story from Constantinople in the spring of 1878. He contracted typhus and died there on June 9, having had the honor of being the only newspaper reporter to ever personally start a war and liberate a country. For years afterward, his death was commemorated by grateful Bulgarians at an annual requiem mass in Tirnova.

Churchill Reports from the Boer War

Another late 19th-century correspondent made his name in Africa, and quite a name it was—Winston Churchill. The aristocratic Churchill, son of Lord Randolph Churchill and his beautiful American-born wife, Jennie Jerome, had entered the British Army in 1894 and served with the 4th Hussars in India, where he wrote for the London Morning Post in his spare time. With an indefatigable nose for adventure and self-promotion, Churchill managed to get himself seconded to the 21st Lancers in time for Lord Horatio Kitchener’s famous punitive expedition against the Muslim army of the Mahdi in the Sudan. Joining the army outside Omdurman in late August 1898, Churchill arrived just in time to take place in the last great cavalry charge in English history.

Riding into the swirling midst of sword- and spear-wielding dervishes, Churchill fired away with his Mauser pistol, killing several tribesmen and barely managing to escape with his life back to his own lines. There he beheld the other survivors making their way from the field, “a succession of grisly apparitions; horses spouting blood, struggling on three legs, men staggering on foot, men bleeding from terrible wounds, fish-hook spears struck right through them, arms and faces cut to pieces, bowels protruding, men gasping, crying, collapsing, expiring.” The charge, Churchill told readers back home in England, “was of perhaps as great value to the Empire as the victory itself. England may rise refreshed and, contemplating the past with calmness, may feel confidence in the present and high hope in the future. We can still produce soldiers worthy of their officers—and there has hitherto been no complaint about the officers.”

Two years later, Churchill went to South Africa to cover the newly started Boer War. Once more combining the roles of army lieutenant and newspaper correspondent, Churchill eagerly boarded a train bound for the front. When it was intercepted by Boer commandos, Churchill narrowly missed being shot for carrying a sidearm while “masquerading” as a correspondent. Only the fact that he had dropped the gun before being taken prisoner prevented the future prime minister from being killed at the age of 24. Imprisoned in a makeshift jail at Pretoria, Churchill subsequently escaped and made his way across 300 miles of hostile bush to Lourenco Marques, where he sent a stalwart dispatch to the Morning Post: “I am very weak but I am free. I have lost many pounds but I am lighter in heart. I shall also avail myself of every opportunity from this moment to urge with earnestness an unflinching and uncompromising prosecution of the war.” His escape, and the best-selling book he wrote about it, London to Ladysmith via Pretoria, made Churchill famous and set him on his way to becoming, four decades later, England’s greatest modern prime minister.

The Rough Riders Make the News

Another well-bred and adventurous young aristocrat—this time an American—also traded on his experiences in a foreign war to rise to the heights of political power. His name was Theodore Roosevelt, and although he was something of an author himself, his glamorous service in the Spanish-American War was left to others to recount. In this, Roosevelt had the good luck to be friends with the most famous correspondent of his day, New York Journal contributor Richard Harding Davis. By the time the war had begun in April 1898, Davis’s flamboyant boss, Journal publisher William Randolph Hearst, had spent months preparing the public for the noble undertaking. Caught up in a press war with rival publisher Joseph Pulitzer of the New York World, Hearst shamelessly beat the drums for war, wiring freelance illustrator Frederick Remington (who was already in Cuba and worrying about the lack of action), “You furnish the pictures and I’ll furnish the war.”

A battalion of reporters, photographers, and artists descended on Cuba that spring. Besides Davis, the best-known—and far and away the most talented—was the brilliant young novelist Stephen Crane, who had created a sensation three years earlier with his Civil War novel, The Red Badge of Courage. The almost suicidally fearless Crane—“The coolest man, whether army officer or civilian, that I saw under fire at any time during the war,” Davis marveled—strode around in a white linen raincoat, habitually smoking a cigarette, while Spanish marksmen peppered the ground around him. No admirer of Roosevelt, with whom he had crossed swords while Roosevelt was assistant police commissioner of New York, Crane correctly reported the first encounter of the Rough Riders at Las Guasimas as “a gallant blunder,” criticizing Roosevelt’s handpicked unit for its “remarkably wrong idea of how the Spanish bushwhack.” Davis, who had also termed the affair “an ambush,” rushed into press with a follow-up story that sought to deflect criticism of Roosevelt by claiming absurdly that there was “a vast difference between blundering into an ambuscade and setting out with full knowledge that will find the enemy in ambush.”

Roosevelt and Crane studiously avoided one another during the days leading up to the climactic battle of the war, at San Juan Hill on July 2, 1898. There the Rough Riders, with Roosevelt in the lead, made one of the most dramatic charges in American history, routing Spanish defenders from their fortified position atop Kettle Hill (Davis incorrectly confused Kettle Hill with San Juan Hill, which was beside it, in his report). Even Crane had to admit that the charge, made without orders and in the face of withering rifle fire, was remarkable. “It was the best moment of anyone’s life,” he conceded generously. For his part in the battle, Roosevelt later was awarded a much-delayed Medal of Honor, and traded on the famous exploit to win election first as governor of New York, then as vice president to William McKinley, and finally to the presidency when McKinley was assassinated by an anarchist in 1901. Crane’s legacy was less fortunate. He contracted a serious fever, probably malaria, in Cuba’s tropical heat, and it quickly developed into tuberculosis. Eighteen months later he was dead, still a few weeks shy of his 29th birthday.

Jack London and the Russo-Japanese War

Crane’s work as a war correspondent encouraged another famous American author, Jack London, to accept a roving commission from Hearst to cover the Russo-Japanese War in 1904. London, a hard-drinking former oyster pirate and Klondike gold miner, had risen to fame as the author of The Call of the Wild. “I entered upon this campaign with the most gorgeous conceptions of what a war correspondent’s work in the world must be,” London recalled later. “I remembered Stephen Crane’s description of being under fire in Cuba. I had heard of all sorts of conditions of correspondents in all sorts of battles and skirmishes, right in the thick of it, where life was keen and immortal moments were being lived. In brief, I came to the war expecting to get thrills. My only thrills have been those of indignation and irritation.” Frustrated by the tight control of war news by Japanese commanders, London finally exploded, punching a soldier who was stealing his horse’s fodder and getting arrested by the authorities. Only a personal telegram from Richard Harding Davis to President Roosevelt prevented London from being court-martialed and executed by his captors.

The heavy censorship of the Russo-Japanese War foreshadowed the even tighter control of war news by the United States and her western allies in World War I. The correspondent’s job ceased being a romantic gallop on horseback to the front and became a ceaseless wrangle with Army bureaucrats behind the lines. Lord Kitchener, in command of Britain’s armed forces, had long despised journalists—he called them “drunken swabs”—going back to his unhappy experience with Winston Churchill at Omdurman. He instituted tight control of correspondents, saddling each journalist with a “conducting officer” who traveled at his side, read his dispatches, and told him when and where he could visit the front. In addition, Kitchener issued orders making it a shooting offense to be caught taking photographs of the war in the trenches, resulting in World War I being perhaps the least photographed major war in modern history. When all else failed, the Army appealed to the correspondents’ sense of patriotism. Philip Gibbs of the London Daily Chronicle noted ruefully, “We wiped our minds of all thought of personal scoops and all temptation to write one word which would make the tasks of officers and men more difficult or dangerous. There was no need of censorship of our dispatches. We were our own censors.” This led Gibbs to write of the Battle of the Somme, the bloodiest defeat in British history: “It is, on balance, a good day for England and France. It is a day of promise in this war.”

Censorship in the First World War

America’s most famous war correspondent, Richard Harding Davis, refused to operate under such humiliating limitations. After rushing to the war in time to see the first German troops enter Brussels in 1914, Davis was arrested by German soldiers who found a photograph in his pocket showing him wearing a British-style military uniform (actually a copy of the Boer War-era tunics, which the Anglophiliac Davis had adopted for his personal use). “It is clear that you are a British officer out of uniform, taken inside our lines,” he was told. “You know what that means.” Davis was spared summary execution, but was forced to walk 50 miles to the rear on a bruised ankle. His treatment was less brutal at the hands of the English and French, but no less frustrating. Refused permission to visit the front lines, Davis eventually returned home, saying disgustedly, “The day of the war correspondent is over. I’m not about to write sidelights.”

When the United States entered the war in 1917, General John J. Pershing, commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, instituted similar censorship of American journalists. Pro-British correspondent Frederick Palmer was hired by Pershing to oversee his fellow American correspondents as part of the Army’s G-2 Intelligence Department. Under Palmer’s management, all dispatches were read and censored before being transmitted back to the United States. In one particularly ludicrous instance, a report that grateful French civilians had presented Americans with cases of wine was killed because “it suggest bibulous indulgence by American soldiers which might offend temperance forces in the United States.” Palmer even censored journalists’ expense accounts. Chicago Tribune reporter Floyd Gibbons, violating Palmer’s limitations on unauthorized trips to the front, paid a heavy price when he was machine-gunned by German forces while accompanying a platoon of Marines across an open field near Belleau Wood in June 1918. Gibbons survived the shooting but lost an eye, and from that time on wore a black eye patch that became his trademark.

Expansion of the Press Freedom in World War II

By the time the next American army landed on French soil, in June 1944, press restrictions had eased greatly. Appreciating that the country was in a fight for her very existence, supreme Allied commander Dwight Eisenhower ordered his officers to give accredited correspondents all reasonable assistance. “They should be allowed to talk freely with officer and enlisted personnel and to see the machinery of war in operation in order to visualize and transmit to the public the conditions under which men from their countries are waging war against the enemy,” Eisenhower directed. Provided such official cooperation, most correspondents chose to stick close to headquarters, content to give readers “the big picture.” The celebrated novelist Ernest Hemingway was even given his own jeep and driver to tool about France, where he mostly reported his own misadventures at the head of a highly irregular group of French resistance fighters.

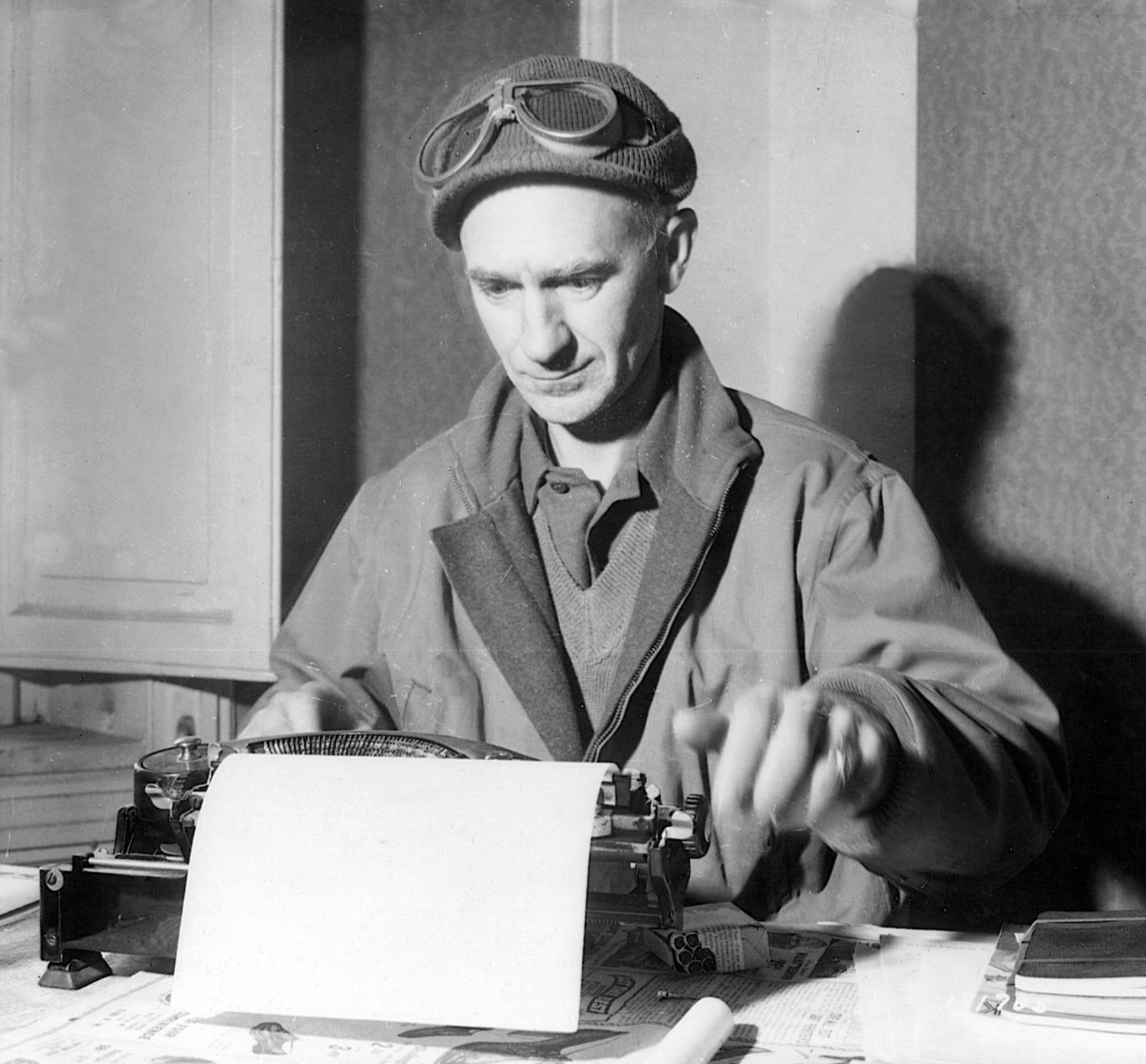

The most celebrated correspondent of World War II took the opposite approach. Ernie Pyle, whose columns ran in an astounding 300 daily newspapers and 10,000 weeklies, concentrated on the individual soldiers, the anonymous, mud-begrimed GIs who tramped across Europe one step at a time. “I love the infantry because they are the underdogs,” he wrote. “They are the mud-rain-frost-and-wind boys. They have no comforts, and they even learn to live without the necessities. And in the end they are the guys that wars can’t be won without.” The diminutive journalist became a familiar sight in the frigid foxholes of Western Europe, sharing his rations and cigarettes and writing about the war from an enlisted man’s humble point of view.

Eventually, Pyle’s self-identification with the suffering soldiers took a toll on his health, and he went back to the United States for a much-needed rest, observing, “If I heard one more shot or saw one more dead man I’d go off my nut.” Pressed to cover the island-hopping soldiers and Marines in the Pacific Theater, Pyle reluctantly pulled on his boots once again, despite having a premonition that he would be killed. On April 8, 1945, just weeks before the war ended, a Japanese machine-gun bullet struck him in the head on the island of Ie Shima, making Pyle one of 37 American journalists to die in the war. His final column, found crumpled in his pocket, lamented: “Dead men in winter and dead men in summer. Dead men in such monstrous infinity that they become monotonous.”

War Correspondents in Televised Wars

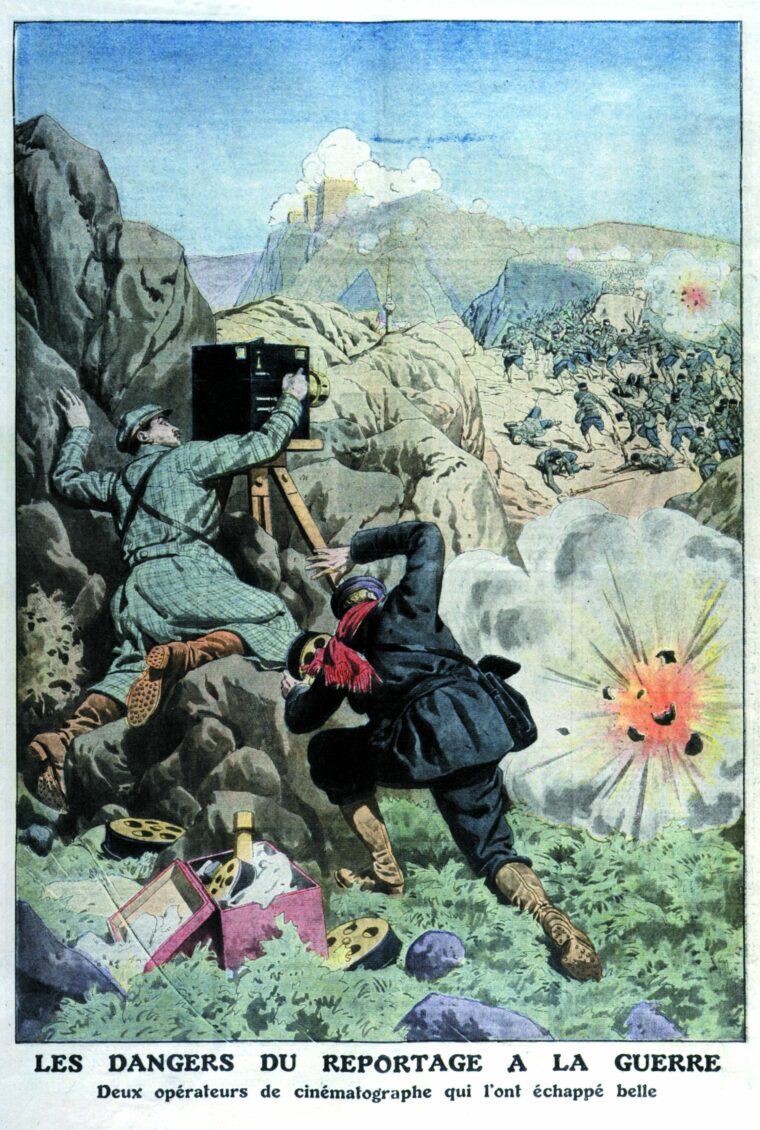

Since World War II, modern technology has largely supplanted the individual war correspondent. Motion pictures, television, radio, and now the Internet have made possible the instant transmission of vivid images from any place on the globe. Vietnam, often called the first televised war, engendered a number of fine correspondents, including David Halberstam, Michael Herr, Peter Arnett, and Sydney Schanberg, but it is largely remembered for its visual images. Burning Buddhist monks, a naked little girl running down a road screaming after an airborne napalm attack, a Viet Cong guerrilla summarily shot in the head on the streets of Saigon—these are the images of a long and increasingly unpopular war, one that played out nightly on the television screens of a horrified nation.

In reaction to the supposedly detrimental effect that press coverage had on the public’s willingness to support the war in Vietnam, military and governmental control of wartime images has tightened dramatically. The ongoing war in Iraq has seen the “embedded” reporters of the first Gulf War replaced by a steadily shrinking pool of isolated journalists hunkered down in the heavily fortified Green Zone, prohibited by regulations—and savage guerrillas in the streets—from presenting a truly comprehensive picture of the war. Even photos of the returning caskets of dead soldiers have been deemed off-limits to the news media by a rigidly controlling administration in Washington. “We died on the wrong page of the almanac,”Tennessee-born poet Randall Jarrell wrote of World War II bomber pilots’ unnoticed deaths. There are no Ernie Pyles in Iraq today, and the American public is all the poorer for it.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments