By William E. Welsh

The Black Death that ravaged England and France for a half-dozen years in the mid-14th century served merely as a brief intermission between the first and second acts of the painfully protracted struggle known as the Hundred Years’ War. The war flared anew in 1355 when English King Edward III’s eldest son, Edward, Prince of Wales, landed with a sizable force in English-owned Gascony (called Aquitaine by the French) to help further his father’s claim to the French crown. Following a successful offensive through southwestern France earlier that same year, the Black Prince, as the Prince of Wales came to be called, set out on another raid in the summer of 1356, this time through central France.

The primary goal of both raids was to advance Edward’s claim to the English crown through his mother, Isabella, the daughter of King Philip IV. One of the thorniest issues was Edward III’s position as Duke of Aquitaine. A king in his own right, he was loath to subordinate himself to another monarch, the French king, when it came to affairs involving England’s continental holdings. Other circumstances that brought the nations to the brink of war were the continued French support for Scotland in its conflicts with England and English dominance of commercial trade with Flanders, then a key part of France.

In 1328, the French invoked the Salic law, which excluded women from the line of succession, to transfer the crown from Charles IV, the last of the Capetian dynasty, to Philip VI, the first of the Valois line. Meanwhile, the young English monarch, just 16 at the time, stated his own claim to the crown, but he was in no real position to contest the transfer. Now, nearly a decade later, Edward III had firmly established himself as king, and the issue again had come to a head. In 1337, Philip announced that the English were no longer entitled to their lands south of the Loire. In response, Edward III proclaimed himself king of France the following year and orchestrated a chevauchée, or raid, into northeastern France, but he hastily withdrew when Philip marched out to meet him with a larger army. The first decisive battle of the Hundred Years’ War occurred when English ships defeated the French Navy near the port of Sluys in 1340. When the French invaded Gascony in 1346, Edward III responded by preparing a fresh invasion of northern France.

The second decisive English victory occurred in northeastern France at the Battle of Crécy, on August 26, 1346. Edward III landed near Cherbourg in Normandy with a large army that included the Prince of Wales and fought his way overland toward Flanders, deciding at last to give battle near the village of Crécy in Ponthieu. After his victory, Edward marched north to Calais, which he captured after a year-long siege.

Neither of the two opponents in the Hundred Years’ War was immune from the Black Death. Like the wind filling the sails of the ships that carried the disease, the bubonic plague whisked west from the Black Sea along popular trade routes. It arrived in Marseilles, France, in January 1348 and at Bristol, England, in September of the same year. No sooner had the sailors tied off their ships at the wharves than the Black Death came ashore and took up residence in the thriving port cities. It gobbled up great swaths of the urban populations and then turned its attention to the countrysides, where it foraged for victims through castles, villages, and hamlets in an effort to satisfy a seemingly insatiable hunger for death. Fully one-third of the population of Europe perished in two years’ time.

When the plague finally ebbed in 1355, the curtain quickly rose on the second act of the Hundred Years’ War. In another quest for the French crown, Edward III ordered the Black Prince to sail at once to Bordeaux with a hand-picked army to join a three-pronged attack similar to the one that had led to the victory at Crécy. Bordeaux lay in the English duchy of Aquitaine, which had been acquired by the English as a fiefdom when Eleanor of Aquitaine married Henry, Duke of Normandy, who subsequently became King Henry II of England in 1152. The English had lost large chunks of Aquitaine over the next two centuries as the French crown tried repeatedly to wrest the duchy from them.

In 1355, Gascon nobles loyal to Edward III traveled to England to beseech their lord for assistance against the French. They requested that Edward send a military force to assist them in countering the inroads made by their nemesis in the region, Jean d’Armagnac, who was the French king’s lieutenant in the Languedoc region. Their request fitted in nicely with Edward’s desire to renew his quest for the crown by striking at the heart of France from several directions at once. This time the English would face off against a new French king, John II, who had succeeded Philip VI to the throne in 1350.

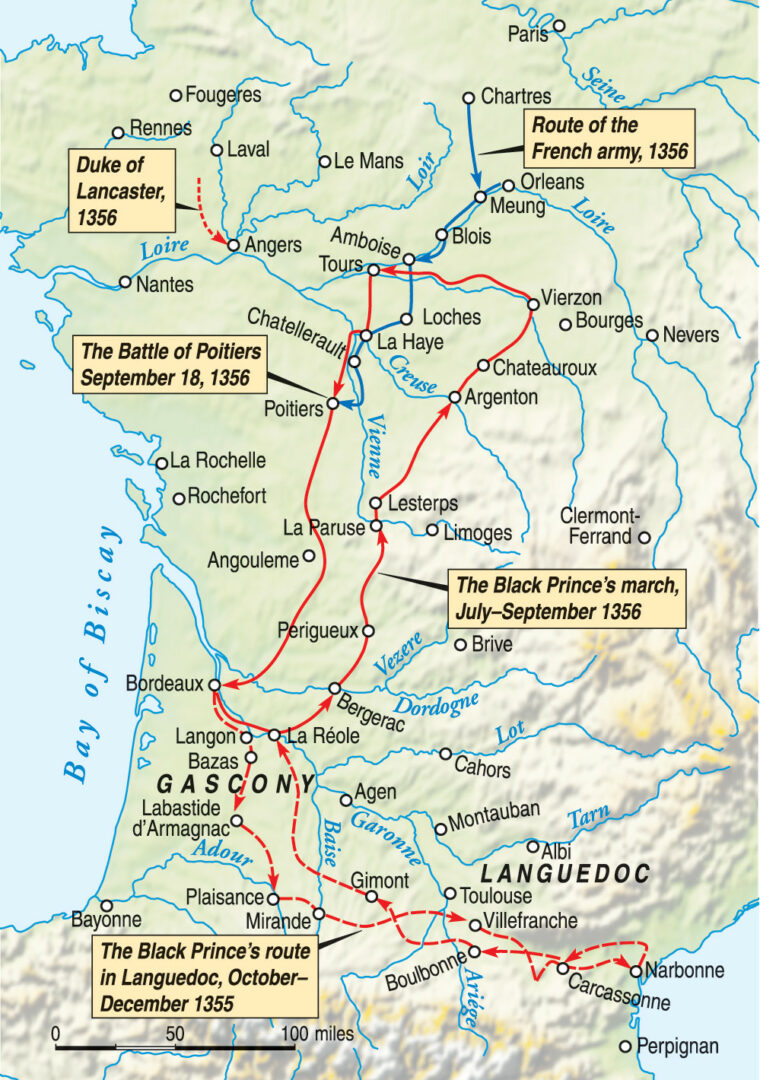

To weaken John’s grip on his nation, Edward III resorted to the familiar medieval strategy of the chevauchée. These lengthy raids, which lasted weeks or even months at a time, were designed to show the population in a particular region that they could not rely on their king for protection. Edward envisioned three chevauchées in 1355—one he would lead himself in northeastern France; one that Henry, Duke of Lancaster, would lead through Brittany; and one that the Black Prince would conduct in southwestern France to avenge the Gascons. Lancaster’s voyage to Brittany was postponed in response to changing circumstances. Meanwhile, Edward III advanced from Calais but retreated in the face of a much larger foe. Upon his return to England, Edward marched north to fight the always troublesome Scots. It fell to the Black Prince to conduct the only major chevauchée against the French in 1355.

The fleet that transported the prince’s 2,200-strong army arrived in Bordeaux on September 20. Nearly a third of the force consisted of hardy archers recruited from Cheshire, a county that lay hard by the border of northern Wales. The other two-thirds of the invasion force consisted of men-at-arms recruited either by the prince himself or by the half-dozen magnates who accompanied him to Gascony. Once in France, the prince tripled his force with the addition of as many as 4,000 Gascon troops loyal to the English crown. On October 5 the chevauchée got under way, with the raiders heading for the region of Armagnac. Rather than turning back after they reached the opposite end of the province, the prince made the bold decision to continue into the Languedoc region, which previously had been spared the ravages of the English.

French forces based in Toulouse under the Count of Armagnac and the Constable of France were no match for the prince’s army. The English army returned laden with plunder to the safety of Gascony on November 28, having suffered no substantial losses. In nearly two months of campaigning, the Black Prince’s army had made a circuit of 684 miles from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean and back again, during which time they burned and sacked 500 castles, villages, and settlements and brought back enough booty to fill a thousand carts.

The prince sent Sir Richard Stafford, one of his lieutenants, back to England in March to raise new levies for his army and to replenish his dwindling supply of arrows in preparation for another large-scale chevauchée. Both recruits and arrows were in short supply because English armies had been embroiled in simultaneous conflicts in France and along the Scottish border. The prince requested 1,000 new bows and 2,000 sheaves of arrows from the king’s ordnance, but received substantially fewer. Meanwhile, Stafford helped recruit 600 additional bowmen from Cheshire and other English counties. In addition, 125 more men-at-arms signed on to fight with the prince. Stafford and the reinforcements arrived in Bordeaux on June 19 and were quickly assimilated into the prince’s army.

The now-familiar strategy of a multipronged attack against the French was launched once again in late summer 1356. While the Duke of Lancaster and the Prince of Wales led chevauchées in northern and central France, respectively, a force led by King Edward III was blocked from crossing the Channel by an Aragonese fleet allied with the French. Lancaster landed in Normandy about the time the prince’s reinforcements arrived in Bordeaux. At the head of a 2,000-man force, the duke overran several French-held towns during the first week of July. He also reinforced the strategic fortress of Breteuil, held by a Navarrese garrison allied with the English, before executing a rapid retreat when a large army under John II reached the fortress on July 12. Aware that the Black Prince was planning a second major chevauchée into the heart of central France, Lancaster sent word that he would attempt to rendezvous with him in the vicinity of Tours. While John began a protracted siege of Breteuil, Lancaster slipped into Brittany and launched a second chevauchée south toward Touraine, where he hoped to join forces with the prince.

The objective of the prince’s second chevauchée was Orleans, in the Loire Valley. The purpose was much the same as the so-called Grand chevauchée of 1355. Just as he had damaged the schemes of Jean d’Armagnac, the prince hoped to do the same to the reputation of the Count of Poitiers, who was King John’s third son and new lieutenant in the Languedoc region. As they had done during the previous chevauchée, the English intended to ravage the French countryside through which they marched, burning towns, villages, and farms to show those loyal to the French crown that they were inadequately protected. At Bergerac, in Guyenne, the prince assembled an army of about 9,000 troops. Leaving behind a garrison of 3,000 to protect Gascony, he left Bergerac on August 4, crossed the Vienne River 10 days later, and instructed his troops to unfurl his banner to signal that the destruction was to begin immediately.

As the prince’s army marched north, John set plans in motion to contest his advance and bring his army to battle. To do so, he had to extricate himself from the siege of Breteuil, which had dragged on for more than a month. If the fortress could not be carried by arms, it might be carried by bribery, the French monarch decided. To appear victorious, the king paid the Navarrese a large sum of money to abandon the castle and relocate to their fortifications on the Cotentin peninsula. Once free of that commitment, John marched his army to Chartres, where he hoped to assemble a more mobile force to pursue the Black Prince. While the French king waited for reinforcements, which included a contingent of Scots under Lord William Douglas, the Count of Poitiers followed orders from the king to countermarch to Tours to protect the key crossings over the Loire River.

Less than two weeks after the prince had crossed the Vienne, an advance party led by the Captal de Buch seized the fortified town of Vierzon on the Cher River. On August 26, the Gascon leader oversaw the pillaging of the town, which he then put to the torch after his troops had carried off everything of value. At this point, the outriders of each army made contact and fought a series of sharp skirmishes. The English knights John Chandos and William Audley crossed the Cher with their scouts and reached the town of Aubigny on August 28. Their orders were to seize an unprotected river crossing. Above Aubigny, the English reconnaissance party tangled with an enemy column led by Phillippe de Chambly, who went by the name of Grismouton and was one of several French scouts sent to delay the English until the king arrived with the main army. Although the English overpowered the French, who fled the field, Chandos and Audley failed to seize a crossing.

The Black Prince’s army far outnumbered the French scouts operating south of the Loire. On August 28, lead elements of the prince’s force arrived at Romorantin, deep behind enemy lines. The prince was desperately trying to make contact with friendly forces under the Duke of Lancaster on the north bank of the Loire River, while enemy forces under King John were converging on his position in an effort to bring the invaders to bay. As the English moved west along the valley of the Cher River, they encountered 300 lancers led by the French nobles Amaury de Craon, Jean le Maingre (also known as Boucicault), and Hermite de Chaumont. The small force, which had been shadowing the English for almost a week, ambushed the scouts riding ahead of the main body of the English army. Following a sharp clash, the French sought refuge inside the castle of Romorantin.

The English made a coordinated attack on the walled town on August 31. English and Welsh archers fired cascading volleys of arrows to drive the defenders from their posts and allow their own men-at-arms to carry the position. The same procedure was repeated later that day for the outer curtain of the citadel. Still the French refused to surrender, retreating to the safety of a large stone keep. The battle grew in intensity as the English employed all the fiendish tools of siege warfare over the next three days in an effort to force the defenders to capitulate. They built stone-throwing machines and assault towers, began digging under the walls, and launched simultaneous assaults from different directions. They also set fire to a tunnel their miners had dug beneath the castle’s foundations. The fire spread out of control, eventually engulfing the castle in flames. The following day, the defenders agreed to an unconditional surrender. The Black Prince tarried in Romorantin until September 5 before continuing west along the old Roman road toward Tours and Poitiers.

Because the French forces had mobilized to prevent the English army from crossing the Loire, the prince abandoned his original objective of Orleans and focused instead on effecting a junction with Lancaster. The prince’s scouts probed the Loire for a crossing above Tours, but they found the bridges either too well guarded by the enemy or destroyed altogether. While he waited at Montlouis for word from Lancaster, the French converged in various columns on Tours. On September 8, John arrived upriver in Meung-sur-Loire where he joined forces with the Count of Poitiers. Two days later the combined French army crossed at Blois to the south bank of the Loire and began a rapid march to overtake the Black Prince.

Meanwhile, the French Dauphin Charles arrived in Tours on September 12 and joined forces with Marshal Jean de Clermont. Around that same time, Lancaster attempted to cross the Loire downriver from Tours at Les Ponts-de-Ce, but he was repulsed by the French. The Black Prince tarried four days at Montlouis for word from Lancaster, but he was forced to turn south when he realized that French forces were closing on him from both east and west. A papal delegation led by Cardinal Talleyrand approached the prince on September 12 to negotiate a peace, but the overture was rebuffed.

The Black Prince remained unaware that the Duke of Lancaster was unable to reach him. He moved south from the Loire to the village of Chatellerault, where he waited for three more days for word from Lancaster. The prince already was in full retreat and the delay would prove costly if he wished to avoid battle with John’s larger army. In the interim, the dauphin and Clermont joined the king’s army as it marched south. Rather than follow in the footsteps of the prince, John stayed to the east in the hope that he could get ahead of the English and block their retreat to Gascony.

On September 17, the Black Prince finally abandoned hope of making contact with Lancaster and continued south. Sensing that the French main army was shadowing him, the prince left the open road for the safety of a more secluded path through the forest. By that time, John already had cut the English line of march. Having reached the town of Chauvigny on September 15, the French army crossed the Vienne River the following day and changed course from south to west to intercept the prince’s army. When the prince reached the road from Chauvigny to Poitiers, he discovered to his surprise that the French had already passed by, headed in the direction of Poitiers. Fortunately for the English, the French were unaware of the exact location of their foe. The prince crossed the same road the French were on and continued south through the forest, hoping to regain the main road south of Poitiers. The prince’s decision to move his entire army through the forest was an unusual one for a medieval commander and something that John did not expect. It was now the English army’s turn to shadow the French. Thinking that the English were still ahead of him, the French monarch continued toward Poitiers.

The two armies clashed when Gascon scouts riding ahead of the main English army ran headlong into the French rear guard at La Chaboterie. When John heard of the fight at the manor there, he turned his army around and led it into camp north of the Roman road between Poitiers and the village of Savigny-Levescaut. The French army, camped in battle formation, had about 11,000 men altogether, comprising 8,000 mounted men-at-arms and 3,000 infantry and crossbowmen. To contest the French, the Black Prince had 6,000 men under his command, including 3,000 English and Gascon men-at-arms, 2,000 English and Welsh archers, and 1,000 Gascon infantry. By selecting the proper defensive position, he hoped to offset the French superiority in numbers and bring about an equal contest.

On the morning of September 18, the prince’s army left the protection of the great forest between the Claim and Vienne Rivers and marched west along the banks of the Moisson River past the Benedictine abbey at Nouaillé. The English army turned north to meet the French by crossing the Moisson at the Gue de l’Homme ford. The prince’s army marched north along a wagon track at the edge of the Nouaillé Wood behind the abbey and began deploying on rough terrain facing west. Rather than deploy the vanguard farthest from the ford, the prince purposely placed the rear guard at the front, in case a retreat became necessary. The rear guard under Salisbury commanded the English right flank, the prince commanded the center, and the Earl of Warwick commanded the left. Supporting Salisbury and Warwick were the Earls of Suffolk and Oxford, respectively. Anchoring both ends of the English position were bowmen deployed slightly forward in a favorable position to fire on the attackers advancing to engage them. Behind the main battle line the prince stationed a reserve of about 400 archers and a few hundred mounted men-at-arms under the command of the Captal de Buch.

The archers on the right flank, who found themselves on more level ground, dug trenches to make it difficult for a mounted foe to reach them. This was unnecessary on the English left flank, where the archers took up positions among the soft, marshy ground alongside the Moisson known as the Champ D’Alexandre, where enemy cavalry would have difficulty operating. A thick hawthorn hedge, which divided the rough terrain from the farm fields beyond, ran almost the entire length of the English battle line This natural obstacle afforded excellent cover for the dismounted English men-at-arms who would receive the brunt of the French attack. The hedge had two gaps wide enough for only about four or five men to pass through. This meant that the attackers would not only have to force the gaps but also cut additional openings to get at the English.

While the position taken by the English afforded them good cover to repulse an attack, their physical condition left much to be desired. Having marched more than 300 miles, the troops were near exhaustion. They were hungry and thirsty, having had no opportunity to forage for food or water on their trek through the woods the previous day. Cardinal Talleyrand tried to broker peace again on September 18, but the French would not agree to anything but unconditional surrender. John believed that he had the Black Prince trapped, and he planned to bag his prey the following day.

The sun rose over the battlefield of Poitiers shortly before 6 am on September 19. The English were in the process of withdrawing. The prince had ordered Warwick to begin pulling back his division before daybreak, and Warwick had been in motion for about an hour. The French were busy before daylight as well. They marched from their camp to the south side of the road to Poitiers and formed up opposite the English position, well out of bow shot. The French deployed in three large “battles,” or divisions. The first division was nominally commanded by the 18-year-old Dauphin Charles, who was guided by experienced veterans such as the Duke of Bourbon. The second division was commanded by the Duke of Orléans, the king’s brother, and included the king’s sons, Louis and John, the Counts of Anjou and Poitiers, respectively. The third division was commanded by the king himself, who was accompanied by his youngest son, Philip.

Wary of making the same mistake that had doomed the French army under Philip VI at Crécy a decade before, the king agreed to try different tactics. He sent one of his most trusted and experienced knights, Eustache de Ribbemont, to reconnoiter the English position. Ribbemont reported back that the enemy position was strong, protected by a nearly unbroken hedge. Ribbemont suggested, and the king agreed, that the French should send two separate groups of cavalry under Marshals Arnaud Audrehem and Jean Clermont to clear the English archers from the wings. After this was done, the French men-at-arms would attack the main English line on foot. The idea of attacking dismounted was contrary to the way French knights were trained and equipped to fight. For the tactic to succeed, the king and his lieutenants would have to exercise tight control over their troops and maintain close communication between the various elements of the army to keep sufficient pressure on the English. It was a bold gamble intended to shake the curse of Crécy.

The marshals tasked with dispersing the bowmen on the two flanks of the English army each led about 250 mounted knights. Clermont would strike the archers on the enemy right flank at the northern end of the Nouaillé Wood, while Audrehem would strike the archers on the enemy left flank near the Champ d’Alexandre. When Audrehem ascertained that some of the English were withdrawing, he called for an immediate attack before the English could escape. Although he was reluctant to attack the English in such a strong position, Clermont had no choice but to launch his attack at the same time.

Audrehem lowered his lance and led a disjointed charge across the open ground toward the Earl of Warwick’s banners. The archers were not among the main column but were hidden in the marshes along the Moisson in a position that paralleled the French charge. As soon as the cavalry advanced, the English bowmen unleashed a torrent of arrows that mostly glanced off the armor plates on the front of the horses as they thundered over the open ground. Seeing the arrows fall ineffectively to the ground, Oxford ordered the bowmen to shift to the left, where they could fire at the unprotected flanks and rear of the French horses. English arrows were soon striking home and horses began crashing to the ground, throwing their riders headlong or pinning them under their bodies, while other horses refused to advance or turned back toward friendly lines. Audrehem’s charge was broken before it even reached the English line. Audrehem was captured, while a badly wounded Lord Douglas was dragged to safety by his men.

Clermont led his knights straight for one of the gaps in the hedge on the right flank of the English position. Salisbury’s archers, who were well protected behind the trenches they had dug to impede the cavalry charge, fired rapid volleys, each of which contained hundreds of arrows. Capable of firing a minimum of 10 aimed shots a minute, the bowmen gave the charging horsemen a deadly greeting. When the French horsemen who survived the wall of arrows reached the hedge, they spurred their horses anew to pass through the breach. Suffolk, whose job was to support Salisbury’s defense, rushed his men-at-arms to the opening to assist the archers in repulsing the enemy.

The two sides were soon gripped in a swirling melee in which swords and axes tore holes in armor and mangled bodies and limbs. The elderly Suffolk, astride his horse, beseeched his men to hold the line. While Suffolk fed more men into the fray, Salisbury drew his sword and swung it until it dripped with blood. The French cavalry fought savagely, but without reinforcements it soon began to shrink back. Clermont, who had been accused of cowardice earlier by Audrehem for his reluctance to attack, was killed during the action. The French cavalry disengaged from the English right flank, and the survivors rode or walked away from the fight.

The cavalry charge, like the overture to a symphony, was a harbinger of larger assaults to come. When the last of the cavalry had left the field, the English watched awestruck as the 4,000 men who formed the dauphin’s division began marching slowly toward them. The Black Prince moved all the archers from his reserve forward to contest the dauphin’s attack. A rain of arrows fell on the French as they advanced across the open ground. The long French line engaged all three of the prince’s divisions at once. While some of the French bunched up to force their way through the two gaps in the hedge, others hacked at the hedge to form new openings for themselves and those who pushed forward behind them. Those trying to advance through the hedge were pierced by arrows fired at near point-blank range.

The two sides grappled with each other in a fight to the death. The French had the most success against Salisbury’s rear guard on the right flank. When the English line in that sector began to buckle, the prince rushed reinforcements on foot to restore the line. As time dragged on, the fighting disintegrated into a series of fierce local struggles that allowed the English to reinforce each point of crisis. The fighting in different sectors shifted forward, then backward, as the French tried to press any advantage. After two hours, French trumpets signaled a general retreat. During the two-hour ordeal, the Duke of Bourbon was slain and the dauphin’s standard was captured.

From John’s vantage point in the rear, it did not seem that the dauphin had in any noticeable way weakened the English position on the battlefield. With the outcome of the battle far from clear, the French monarch ordered both the dauphin and his other two sons in the second division to leave the battlefield to prevent their capture. The escorts who rode forth to carry out the king’s orders could be plainly seen by all of the troops in the second division, many of whom interpreted the development as an indication that the battle was going poorly. After this was accomplished, it was time for the Duke of Orleans to advance with his division. But rather than advancing, the entire second division promptly retired from the battlefield without making any attempt to engage the enemy. Having witnessed the failure of the first division to break the English line, as well as seeing the king’s sons removed from his division, the duke believed the day was lost and was loath to sacrifice his troops in a lost cause.

The battle did not stop simply because a third of the French army left the field. The king fully intended to defeat the English, risking possible death or capture to achieve his goal. While the second French division was retiring and the third division was preparing to advance, the prince ordered his archers to replenish their arrows by removing them from the dead in front of the English line. Many of the prince’s officers urged him to switch over to the attack. The most vocal was Chandos. “Ride forward, sir, the days is yours,” he urged. “Let us make straight for your adversary the King of France, for it is there that the battle will be decided. I am certain that his valor will not allow him to flee.”

But the Black Prince had another plan in mind. First, he reorganized his main battle line into one cohesive division. Next, he pulled some of the men-at-arms from the main battle line and instructed them to mount up. Then he instructed the Captal de Buch to take about 160 mounted men on a wide sweep around a covering hill into the rear of the French to fall on the enemy left flank. When the Captal de Buch was in position on a rise behind the French army, he was to display the banner of Saint George to signal the prince that he was launching his attack. At that time, the prince intended to unleash Audley with the rest of the mounted men-at-arms in a frontal attack on the French right flank.

The French king was resolved to press the last attack. “Forward, for I will recover the day, or be taken or slain,” he said to his aides. When the officers gave the signal, a chorus of trumpets sounded the advance. The rank and file of the English army were stunned to see a fresh division advancing to the attack—they had believed the battle was already over. Fluttering above John’s division was the crimson oriflamme, the great war standard of France, which was brought forth only in times of great danger when the fate of the nation hung in the balance. The French advanced behind a wall of shields to protect them from the English arrows. But the English archers had few arrows left to shoot so late in the battle. The French line paused, and a line of crossbowmen advanced to the front on both wings and fired their bolts at the English. Few if any found their target since the English were still well protected behind the hedge. When the advance resumed, those English bowmen with any arrows left fired them at the enemy, then drew their swords and daggers and joined the battle line.

Just at the moment when the two armies were about to clash on the edge of the Nouaillé Wood, the Captal de Busch raised the banner of Saint George and rode from the high ground on the east side of the Roman road down into the shallow valley where John’s division was deployed. When he saw the Gascon’s signal, the Black Prince ordered Audley to charge the French right flank. Audley scattered the crossbowmen and rode until he was behind the French right flank. Having a shorter distance to ride to reach the enemy, Audley was among the French even before the Captal de Buch had reached his objective on the opposite flank. Seeing the French pause in pressing their attack, the prince ordered a general advance all along the line of battle.

Struck on two sides by fierce cavalry attacks, the strongest of the three French divisions lost all cohesion. Struggling for their lives, French men-at-arms fought in isolated groups that were quickly surrounded by the enemy. Gradually the French were forced south into the marshes of the Champ D’Alexandre. With their backs against the Moisson, there was no escape—only death or surrender. The chronicler Geoffrey le Baker captured the horror of those last minutes: “Then the standards wavered and the standard bearers fell. Some were trampled, their innards torn open, others spat out their own teeth. Many were struck fast to the ground, impaled. Not a few lost whole arms as they stood there. Some died, wallowing in the blood of others, some groaned, crushed beneath the heavy weight of the fallen, mighty souls gave forth fearful lamentations as they departed from wretched bodies.” Any remaining French resistance was extinguished when Geoffrey de Charny, the knight holding the oriflamme, was struck down and the banner fell to the ground to rest among the dead and dying.

Not far from the oriflamme, the king fought on against fierce odds. Nearly overwhelmed on several occasions, he was saved when his 14-year-old son Philip shouted to him to watch his left or right as a new threat emerged. But once the banner fell, the king decided to surrender if he could find a knight who could protect him. A number of enemy soldiers grabbed at his clothing, but it was Denis de Morbeke, a French exile serving in the prince’s retinue, who finally won the king’s surrender. When other soldiers tried to seize the king from de Morbeke, Warwick rode up and demanded the prisoner on behalf of the prince.

After eliminating all resistance in the Champ D’Alexandre, the English and their Gascon allies turned their attention to overrunning those parts of the French army retreating in the direction of Poitiers. When overtaken by their pursuers, many of the wealthy French knights surrendered, but hundreds of common men were slain on the road to Poitiers or massacred at the city gates when the townspeople refused to let them in. Altogether, the English captured about 1,000 knights worth ransoming. The French lost about 3,000 men, or one-quarter of their army, in the battle. The English lost substantially fewer.

Some of the captured knights were ransomed quickly so that they would not encumber the army’s return march. On September 22, three days after the battle, the English took the remaining prisoners and the booty acquired from more than a month of campaigning in the French heartland and marched back to Gascony, arriving in Bordeaux on October 2. The defeat at Poitiers and the capture of King John was a substantial setback for the French crown. Through the Treaty of Bretigny in 1360, Edward was freed from his feudal obligations to the king of France, the French agreed to pay a large ransom to win John’s freedom, and the English won control of a half-dozen additional provinces in southwestern France. Three years later, the Black Prince became ruler of the principality of Aquitaine, restored to its former greatness for a time, where he established an opulent court that lasted for nearly a decade until his poor health compelled him to sail home to England. After that, English control of Aquitaine, like its savior, withered away until it was no more than a memory of the great victory he had won at Poitiers.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments