By William Stroock

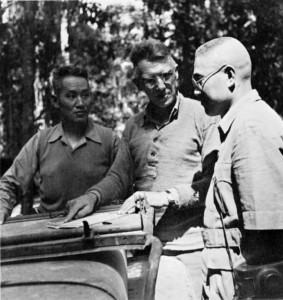

When the United States entered World War II in December 1941, Joseph Stilwell was already a highly regarded officer. Having impressed U.S. Chief of Staff General George Marshall with his grasp of maneuver warfare during Louisiana exercises in 1940, Stilwell expected to become a corps or even army commander in the coming war with Germany. Instead, mainly because he had traveled widely in China during the 1920s and 1930s, Stilwell was tapped by Washington to lead American efforts in China.

“Vinegar Joe” and “Peanut”

Nicknamed “Vinegar Joe,” Stilwell did not make friends easily. He detested the British officer class, which he thought was snobbishly addicted to pomp and privilege, and he was no fonder of intractable Chinese Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, whom he nicknamed “Peanut” for his chronic timidity and foot dragging in the face of the enemy. Chiang, he said, was nothing more than “a grasping, bigoted, ungrateful little rattlesnake” who was more than happy to receive American supplies and equipment, while letting someone else—the British or the Americans—do his fighting for him.

Despite Chiang’s continuing intransigence, President Franklin D. Roosevelt was determined to keep supplying his forces with Lend-Lease materials. By doing so, he hoped to keep China in the war, a goal that was seen by Washington as a worthwhile end unto itself. American planners considered China a potential staging area for air raids against Japan and a jumping-off point for an eventual invasion of the Home Islands. More importantly, if China was defeated, or if Chiang got fed up with the war and made a separate peace with Japan, dozens of Japanese divisions would be free to operate elsewhere against the Allies. Roosevelt also felt a great personal connection with China; his grandfather, Warren Delano, had enjoyed many lucrative business dealings with the giant Asian country.

The Japanese Advance Toward the Burma Road

By 1941, a third of China, including all of its seaports, was in Japanese hands. Still, the Chinese Nationalists were not entirely alone. During the opening years of the Sino-Japanese War, Chinese forces had been supplied via the Burma Road, a narrow route that began at Bhamo and entered China near Lashio. There was also a railway that ran from Mandalay north to the border town of Myitkyina (pronounced MITCH-i-na), 200 miles to the north.

The Japanese invasion of Burma in 1941 posed a dire threat to the Burma Road. As the British reeled before the Japanese onslaught, American authorities led by Stilwell finally convinced Chiang to commit his forces to the battle. Chiang agreed to send the understrength Fifth and Sixth Armies to Burma and place them under Stilwell’s direct command. Stilwell and his Chinese troops entered Burma in mid-March 1942 and raced south to the important rail hub of Toungoo on the Sittang River. The first to arrive on the scene was the relatively well-armed Chinese 200th Mechanized Division. The 200th dug in along the Sittang and awaited an attack by the Japanese 56th Division.

Chiang’s 200th Division in a Rout

Outnumbered and without air support, the 200th repelled several Japanese attempts to cross the Sittang and get around its flank. Over the next several days, however, the Japanese slowly ground down the 200th Division and by March 22 had turned both its right and left flanks. Meanwhile, the Chinese 22nd Division, commanded by General Liao Yao-hsiang, had taken position north of Toungoo, with the 96th Division following close behind. A strong counterattack could have stopped the Japanese advance in its tracks, and Stilwell worked desperately to organize one. However, most Chinese commanders were experts at doing nothing and had ready-made excuses for why they could not obey Stilwell’s orders. By March 30, faced with annihilation, an enraged and dismayed Stilwell allowed the 200th Division to pull out of Toungoo, leaving behind more than 1,000 dead.

The resulting retreat was a rout, with British forces pulling back for India and Chinese troops retreating north in disarray. British General William Slim, who had been sent to Burma to try to rescue the situation, called the loss “a major disaster” and blamed the 22nd Division for not entering the fight. As for Stilwell, he burned with resentment and embarrassment over the forced retreat from Burma. “We got a hell of a beating,” he said when he arrived safely in New Delhi. “We got run out of Burma and it is humiliating as hell. I think we ought to find out what caused it, go back and retake it.”

Building a Chinese Army in India

The fall of Burma in 1942 was viewed by the British as the tragic loss of a royal colony, while the Americans were inclined to lament the closing of the only route through which Chiang’s forces could be resupplied and encouraged to fight. The British saw the liberation of Burma as an “end unto itself,” in the words of Slim, and His Majesty’s government, concerned with liberating Rangoon and Mandalay, had few resources to spare for an operation to reopen the Burma Road. Any such effort, said the British, should fall to Chinese forces. Chiang disagreed, hoping instead that the Allies would increase their supply shipments via the treacherous air route, the “Hump,” over the Himalayas. But as troops and equipment originally meant for China were appropriated by Allied officials for use elsewhere (in one case, several British squadrons in India were transferred to North Africa after the fall of Tobruk), Chiang eventually accepted Stilwell’s offer to train Chinese troops in India. The new force was christened the Northern Combat Area Command, or NCAC.

In 1943 a training camp for Chinese troops was established at Ramgarh, 200 miles east of New Delhi, and placed under Stilwell’s direct command. There, American liaison teams worked hard to prepare Chinese troops for battle. Some 9,000 survivors from shattered Chinese Nationalist divisions in Burma were joined by another 22,000 men flown into camp over the Hump. Chinese foot soldiers were subjected to rigorous physical training and taught the use of rifles, machine guns, and radios. Chinese officers were taught basic tactics and unit coordination. Six weeks of basic training was followed by an eight-day course in jungle warfare. Since the divisions were to be equipped with American howitzers, special emphasis was placed on artillery training. While the Chinese troops were still subject to the hair-trigger brutality of Nationalist discipline, they were surprisingly well treated by the Americans. Troops were regularly fed, paid, outfitted and housed.

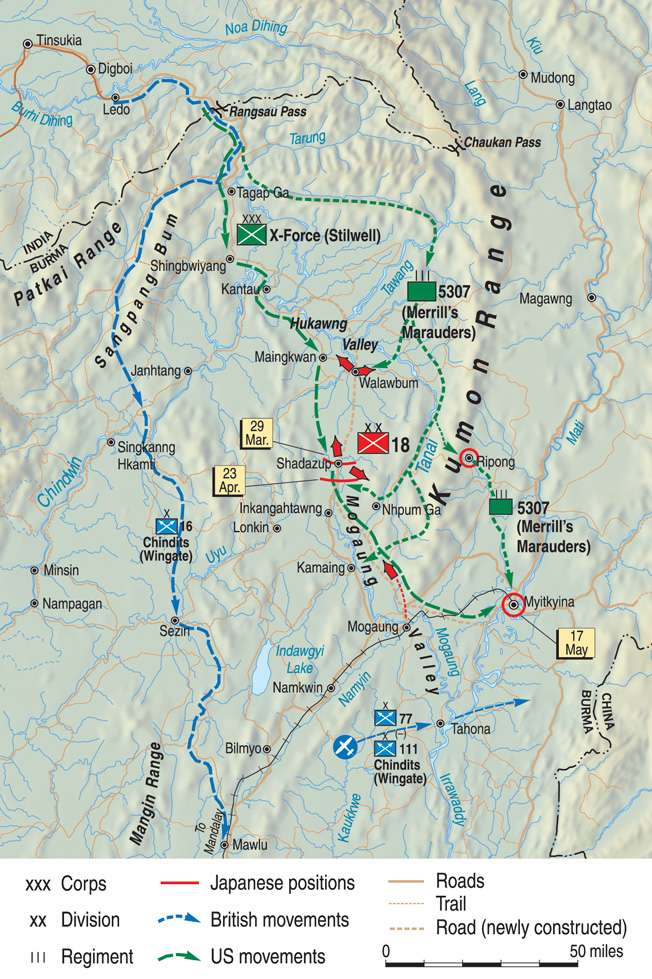

Allied Thrust Against Myitkyina

The Chinese troops would play an integral role in the upcoming Allied offensive. General Slim planned a three-pronged thrust against Japanese forces in northern Burma, with the objective of driving the Japanese out of their enclaves and opening up a road to China. The British IV Corps would lead the southern prong, attacking Japanese forces in Arakan. The central prong would consist of the British Special Force, a body of six light brigades commanded by the eccentric Brig. Gen. Orde Wingate. Special Force was ordered to open several airstrips through which follow-up brigades would be landed to attack Japanese garrisons along the Mandalay-Myitkyina railway.

Myitkyina was the prize, a doorway through which overland supplies could be routed to China. As such, it fell to Stilwell and his retrained Chinese divisions. From Ledo, they would fight their way east through the Hukawng and Mogaung Valleys to Myitkyina in the Irrawaddy Valley. Stilwell, all too familiar with the perils of warfare in Burma, was under no illusions about the difficulties facing him and his men. “We have to go in through a rat hole and dig the hole as we go,” he told subordinates. The steep, jungle-covered mountains, fast-flowing rivers, and fever-ridden bamboo forests were a physical and logistical nightmare. No less an experienced soldier than British Prime Minister Winston Churchill judged Burma “the most forbidding fighting country imaginable,” and he added ominously: “One could not choose a worse place for fighting the Japanese.”

Planning the Offensive

Stilwell had no choice in the matter. Over the summer and early autumn of 1943, NCAC gathered for the planned assault. The Chinese 22nd and 38th Divisions gradually moved to Ledo. At the same time, regiments from the 30th and 50th Divisions flew into Ramgarh, where they retrained. These forces were supported by the 1st Provisional Tank Group, a mixed Sino-American battalion of 60 M3A3 tanks (later augmented by two platoons of Shermans) commanded by American Colonel Rothwell Brown. Also falling under NCAC’s command was the American 5307th Provisional Regiment, better known as Merrill’s Marauders, which was code-named Galahad and commanded by namesake Brig. Gen. Frank Merrill.

Often portrayed by the press as an elite band of commandos, the 5307th was in fact a unit composed of misfits, malcontents, and malingerers gathered from various U.S. Army backwaters. Lieutenant Charlton Ogburn Jr., later a distinguished Shakespeare scholar, took one look at the men he was expected to lead and thought: “The word ‘pirates’ crossed my mind. An assemblage of less tractable-looking soldiers I had never seen. I felt much like a Sunday school teacher in a reformatory.” The 5307th joined NCAC in February 1944.

Leading NCAC into the jungle were hundreds of Kachin scouts, who had spent the last year in Burma waging a relentless guerrilla war against the Japanese. Engineers led by American Brig. Gen. L.A. Pick would follow the Chinese divisions, hurriedly carving a road out of the jungle. In China, more than a dozen Chinese divisions, called Y Force, gathered for an attack across the Salween River. Chiang, typically, would spend the bulk of the campaign manufacturing excuses for why his powerful force remained idle.

Facing NCAC in the Hukawng Valley was the elite Japanese 18th Division, commanded by tough and experienced General Shinichi Tanaka. The 18th was one of the best formations in the Imperial Army. The division had fought in China, participated in the conquest of Singapore, and helped kick the British out of Burma in 1942. Although one regiment, the 114th, had been sent north to aid the Japanese defense of Yunan, the 18th, especially on the defensive, was still a formidable unit.

Beginning the Advance

Stilwell did not intend to impale his newly trained Chinese divisions on the stout Japanese defenses. Instead, he planned to overcome the enemy’s geographical advantages by holding their forces in place with feint attacks while working around the Japanese flank. Even so, the initial offensive into the Hukawng Valley, begun in late October 1943, got off to a slow start, with Japanese patrols impeding the advance of 38th Division. When he encountered stiff Japanese resistance at Yupbang Ga (about 50 miles southeast of Ledo on the Tanai River), General Sun formed a hedgehog and hunkered down for a long battle. Although cut off, the Chinese troops were resupplied by air and held their ground.

Expecting the Chinese to easily give way, Tanaka launched several attacks, all of which failed to dislodge them. On December 21, Stilwell arrived at the scene and immediately ordered the 38th Division to counterattack. The attack began on December 24 with a large, well-placed artillery barrage followed by a steady Chinese advance against determined Japanese resistance. After a week of fighting, the combined assault broke the deadlock and the Allied forces took Yupbang Ga. It was a costly victory. The 38th Division alone lost 315 killed and 429 wounded. Still, it was a momentous triumph for the Chinese Nationalist forces. Not only had they held their ground against the Japanese—they had ultimately pushed them out of their positions. It was a harbinger of things to come.

Pushing the Japanese Back

Before advancing further, Stilwell struck Japanese forces in the town of Taro, on a plain south of Yupbang Ga. He delegated the task to the 65th Regiment, part of the 22nd Division and the 1st Provisional Tank Group. Stilwell began to have trouble with Sun and Liao, who had been told by Chiang to minimize their risks and be as cautious as possible. The only way for either commander to do so was to avoid offensive action. An exasperated Stilwell was forced to go to the front himself and cajole the 65th Regiment’s commander into attacking. Under Stilwell’s critical eye, the advance proceeded slowly but steadily, with the 1st PTG fighting several small battles, one at the village of Kutkai against Japanese light tanks. After clearing out an enemy position in which more than 250 Japanese were killed, the 1st PTG entered Taro.

With his right flank secured, Stilwell resumed the slow slog toward Myitkyina. His next target was Maingkwan, about 25 miles up the Hukawng Valley. While the 65th Regiment of the 22nd Division, the 1st Battalion of the 5307th, and the 1st PTG advanced against Japanese forces, Stilwell ordered the Chinese 66th Regiment to march from Taro to the town of Walawbum, behind Maingkwan, where they were to establish a roadblock across the route leading to Kamaing, the Japanese main line of supply. Advancing on a two-regiment front, Stilwell steadily pushed back the Japanese.

Taking Walawbum

The 1st PTG saw heavy fighting. On the night of March 3, the battalion was ambushed just east of Maingkwan, losing two tanks and an armored bulldozer to Japanese guns. Brown, in direct command of the battalion, ordered his tanks into laager formation and poured fire into the jungle while the better part of a Japanese battalion surrounded him. While the members of the 1st PTG were fighting for their lives, the Chinese 66th Regiment lost its way in the jungle and was unable to take Walawbum. An enraged Stilwell went looking for the regiment himself and, upon finding it, relieved the commander. The advance to Walawbum was temporarily halted.

The task of taking Walawbum now fell to the 5307th. Working with the 113th Regiment of the 38th Division, the 5307th got astride the road south of town, where it received aerial resupply. Knowing that he faced being trapped between Stilwell’s hammer and Merrill’s anvil, General Tanaka launched a fierce counterattack against the Sino-American force. Merrill had deployed the 2nd Battalion astride the road east of Walawbum and the 3rd Battalion on the town’s eastern outskirts. The 1st PTG was held in reserve, and it carved from the nearby jungle an airstrip through which light aircraft flew in supplies. On March 4, Japanese forces probed the 2nd Battalion’s defenses, a series of machine-gun nests, strongpoints, and listening posts. Japanese patrols trying to get around the battalion’s right flank were ambushed in turn by a pair of platoons on loan from the 1st Battalion.

The next day, Tanaka launched several large-scale attacks against the 2nd Battalion, but his forces were unable to make any headway and suffered heavy losses. During the night, the 2nd Battalion, worn out by the day’s fighting, abandoned the roadblock and withdrew to the east bank of a small river. Two Japanese companies followed and tried to cross. They were met by concentrated machine-gun fire and gunned down on the west bank, losing 400 men in a virtual massacre. Refusing to lose any more men in futile assaults on Merrill’s defenses, Tanaka withdrew farther south, toward Kamaing, leaving behind more than 1,500 dead.

On March 7, the 113th Regiment took Walawbum against token opposition. While there was disappointment that the bulk of the Japanese 18th Division had escaped, no one was unhappy with the overall balance sheet, which heavily favored Stilwell. Wrote General Slim, who had been visiting Stilwell’s headquarters at the time of the battle: “Walawbum was an undoubted victory. Although it escaped nearly intact, the Japanese 18th Division was roughly handled and had hurriedly to retreat.”

Jambu Bum

The Hukawng Valley ended at a ridge southeast of Walawbum called Jambu Bum. This was Stilwell’s next target. The disgraced Chinese 66th Regiment was charged with taking the ridge. At the same time, the 1st Battalion of the 5307th, in conjunction with the Chinese 113th Regiment, marched around the Japanese right flank for the town of Shadazup. The Sino-American force slogged through dense, hilly jungle, fighting several skirmishes against Japanese forces. The Chinese and Americans were greatly helped by a body of several hundred Kachin scouts, who raised havoc behind Japanese lines. Ten days later, the Allied forces found a large concentration of Japanese troops resting and at play along the Mogaung River.

On the night of March 28, the 1st Battalion launched a surprise bayonet attack and wiped out the camp. Afterward, the 1st Battalion established a roadblock across the Kamaing road. Tanaka launched two attacks on the roadblock, both of which were stopped with the loss of over 300 men. During the night, the 1st Battalion was pounded by Japanese artillery, but after the drubbing they had received that day, no infantry attack was forthcoming. The next day, they were relieved by the Chinese 113th Regiment. Realizing that a strong enemy force lay astride his line of communications, and with the Chinese 22nd Division making steady progress against Jambu Bum, Tanaka pulled his forces back toward Laban, to the southeast. One battalion of the Chinese 113th Regiment pursued and inflicted further casualties on the Japanese, eventually capturing the village.

Vinegar Joe Keeps up the Momentum

Stilwell built on the momentum gained by his victories at Walawbum and Jambu Bum by moving against the town of Inkangahtawng. While the 22nd and 38th Divisions pushed southeast into the Mogaung Valley, the hard-charging general sent the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 5307th on an end-around run behind Japanese forces. On March 24, the 2nd Battalion surrounded and attacked Inkangahtawng, but was thrown back by heavy enemy fire. The Japanese counterattacked from the direction of the Kamaing road, but the 2nd Battalion repaid the favor and turned back the enemy with heavy losses.

Tanaka reinforced his efforts, sending two battalions south and forcing Merrill to pull his own troops off the Kamaing road and onto a ridge named Nphum Ga. There, Merrill deployed his 2nd Battalion across the hill. One platoon was sent south to the village of Kauri, while Merrill sent the 3rd Battalion five miles north to guard his flank and defend a patch of open ground that was being converted into another airstrip. The first Japanese attack on Nphum Ga, launched near sunset on March 28, was thrown back with ease by the 2nd Battalion.

The Japanese Counters the 2nd Battalion

During the night Merrill, who had fallen ill, was evacuated, leaving the regiment in the hands of Colonel Charles Hunter. Another Japanese attack commenced at dawn on the 29th, but this too failed to make any headway against the dug-in troops. Follow-up efforts from the southwest and the south were also stopped. Under cover of darkness, Japanese forces slowly worked their way around the 2nd Battalion’s eastern flank, but attacks launched on March 30 again were stopped cold. However, the Japanese did manage to get around 2nd Battalion’s western flank and cut the trail linking them with 3rd Battalion. The next day, they hit Nphum Ga from three different directions.

The enemy thrusts pushed the 2nd Battalion back up the hill but failed to breach its perimeter. While the 2nd Battalion was holding on, a combat team from the 3rd Battalion made its way south and tried to reopen the trail. They made it to within a few miles of Nphum Ga before being halted by stiff Japanese resistance. The next day, the 2nd Battalion attacked north but was unable to break through.

The Japanese are Repelled

Fearing that the American forces would link up, the Japanese launched several assaults on the 2nd Battalion’s western flank and managed to push through to the hill. A fierce American counterattack drove the Japanese back into the jungle. The 3rd Battalion pressed on, getting to within a mile of 2nd Battalion’s positions by April 7. That same day the 1st Battalion, which had been force-marched from Shadazup to join the fight, arrived on the scene. On April 9, they finally broke through. After the link up, Japanese forces pulled back, leaving Nphum Ga to the Allies.

Having bought time for Japanese forces fighting the Chinese elsewhere in Burma, Tanaka pulled back toward Kamaing, a reprieve for the 5307th, whose men were exhausted and short of supplies. Stilwell pushed on, and the Chinese 112th Regiment outflanked the Japanese and took up a blocking position east of Kamaing at the village of Setan. The Japanese launched several fierce counterattacks against the 112th, all of which were turned back by the increasingly confident Chinese.

Securing the Mogaung Valley, Myitkyina Now In Sight

With their line of supply cut, Japanese forces inside Kamaing were unable to hold out against Stilwell’s constant pounding, and the town fell to the 112th Regiment. The disgraced Japanese commander, Maj. Gen. Genzu Mizukami, committed ritual hara-kiri. Fighting continued for several days as Tanaka tried to retake the town, but the Chinese troops, reinforced by the 113th Regiment, threw back the general’s desperate efforts. During the course of the battle, the 112th Regiment linked up with elements of Wingate’s 111th Chindit Brigade, which had taken the town of Mogaung to the south. The entire Mogaung Valley was in Allied hands.

Myitkyina itself was now in sight. While the Japanese were being pushed out of Kaming, Stilwell dispatched the exhausted 5307th, now under half of its paper strength, on yet another long trek through the jungle, along with the 88th Regiment of the Chinese 30th Division and the 150th Regiment of the Chinese 50th Division, both of which had just been flown into Burma. They marched over the steep Kumon Mountains and through dense jungle in monsoon-like rain to arrive north of Myitkyina in mid-May. Rather than the town proper, the Sino-American force attacked the airfield to the east. The 1st Battalion of the 5307th attacked and took a ferry on the Irrawaddy River, while the 150th Regiment overran the airfield.

Reinforcements

Stilwell now had troops just outside his prize objective and a means of easily resupplying and reinforcing them. Although surprised by the initial attack, the Japanese were well prepared to meet the challenge before them. The town was garrisoned by the Japanese 114th Regiment, which had returned from Yunan, and the railway between Myitkyina and Mandalay was still open. Japanese reinforcements were rushed to the scene.

Upon receiving word that the airfield was in Sino-American hands, Stilwell flew in reinforcements, including the Chinese 89th Regiment (part of the 50th Division) and a raw American engineering battalion. The first attack was launched on May 18 by the 150th Regiment. It made good progress at first, taking the railhead north of Myitkyina, but was driven out by a Japanese counterattack. To the east, the 3rd Battalion, in conjunction with the Chinese 89th Regiment, attacked the Japanese-held village of Charpate, which fell after a short fight. The 3rd Battalion garrisoned the village while the 89th Regiment took up a position to the southwest. Farther south, the 2nd Battalion occupied the village of Namkwi, astride the railway back to Mogaung. Four allied battalions were arrayed in an arc running north-northeast of Myitkyina, controlling the road, railroad, and airstrip. Japanese forces in Myitkyina were on their own.

Merrill, who had returned from sick leave, gathered his forces at the village of Pamati to the southwest for a final attack on Myitkyina. The Japanese struck first during the last week of May, attacking Sino-American forces at the airstrip. The 3rd Battalion attempted to relieve the airstrip but was repulsed by a stout Japanese defense. Other enemy forces attacked Charpate on the night of May 23 and again the next morning, driving the exhausted Americans out of the village.

The Japanese Withdraw from Mytikyina

The rest of Chinese 50th and 30th Divisions (one regiment each) arrived on the scene, but they were unable to break the deadlock. The 5307th, exhausted beyond all measure, disintegrated in the field, and the survivors had to be flown out and replaced by a pair of battalions of raw troops who were completely ill-equipped and -trained to fight the Japanese. A furious Stilwell berated his commanders and accused the British 111th Brigade of malingering in the vicinity of Mogaung. Slim had to intervene to keep the two commands working together. Luckily for Stilwell, the Japanese offensive into India had been stopped cold, and the enemy forces were in even worse shape. The Japanese garrison in Myitkyina ultimately withdrew in late June. Myitkyina was in Sino-American hands, and the road to China via Burma was open once again.

Success in Burma, Failure in China

While Stilwell and his battle-hardened Sino-American forces were achieving a brilliant victory in the jungles of Burma, the Chinese homeland was going to pieces. Official Nationalist corruption, seeping into every layer of public life, hamstrung the economy and embittered a people already battered by heavy taxation, impressments, and incompetence. Unable to halt the Japanese advance, the 34 Chinese Nationalist divisions in the province were easily steamrolled by the oncoming enemy.

Roosevelt Sides with Chiang, Stilwell Relieved of Duty

Analyzing the situation from Myitkyina, Stilwell suggested to Washington that the Chinese Nationalist division holding the line against communist force in the north be marshaled for a counterattack against the Japanese flank. President Roosevelt followed Stilwell’s advice and sent a message to Chiang suggesting that Stilwell be made supreme commander of Chinese Nationalist forces. Chiang, for his part, did nothing to aid Stilwell or his forces at Myitkyina.

When Stilwell reported Chiang’s continued foot-dragging to Washington, Roosevelt sent the generalissimo an extraordinary message saying bluntly that Chiang’s inaction threatened to close the Burma Road and the Hump. “For this,” said Roosevelt, “you yourself must be prepared to accept the consequences and assume the personal responsibility.” An unapologetic Chiang responded by demanding that Stilwell be relieved. Obsessed with keeping Chiang happy, despite what was amounting to a massive waste of time and resources on an ally determined to do nothing at all, Washington acquiesced. Stilwell was duly relieved on October 18. By then he had pronounced his own verdict on the difficult and underappreciated campaign he had seen through to victory against nearly unimaginable odds. “Myitkyina—over at last,” Stilwell wrote in his diary. “Thank God.” It was an opinion doubtless shared by all the soldiers—American, Chinese, English, and Japanese—who had ever fought in the Burma Theater.

Originally Published February 2010

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments