A delegation from the Kingdom of Hungary seeking military aid to fight the Ottomans undertook a diplomatic mission in the spring of 1395 to a number of great cities in France and Burgundy. They met with Latin rulers and high royalty, including Doge Antonio Venier in Venice, Duke Philip “The Bold” of Burgundy in Lyons, Margaret of Flanders in Dijon, Duke John of Gaunt in Bordeaux, and the regents of French King Charles VI in Paris. Pope Boniface IX, eager to ensure that Constantinople remained in Christian hands, already had thrown its weight behind the venture.

The purpose of the planned military expedition was to roll back the advances of Ottoman Sultan Bayezid I, who had recently extended his empire’s western border to the Danube River. In the final decade of the 14th century, Bayezid was on the offensive in the Balkans. The Ottoman sultan was steadily gnawing his way north through the lesser kingdoms and principalities of the Balkans. Some of these, such as Bulgaria, he conquered outright; others such as Serbia, he coerced into becoming his vassal.

Following the fall of Acre in May 1291, which brought an end to the 200-year lifespan of the Crusader States in Palestine and Syria, the so-called Later Crusades began. These military undertakings, which were put in motion by papal bulls, were not called crusades at the time; instead, they were pilgrimages in which those who signed on were warrior pilgrims said to be “taking the cross,” writes Eric Christiansen in The Northern Crusades. The Later Crusades were directed against pagans and infidels in several theaters, including the Iberian Peninsula, the Balkans, and the Baltic.

Philip of Burgundy was the main sponsor of the Crusader army that would march overland to Hungary to assist King Sigismund. The crusade had been four years in the making and had suffered numerous leadership changes and schedule delays. Through special taxes, Philip raised 700,000 gold francs. His son, 24year-old Count John of Nevers, was picked, not surprisingly, to lead the Franco-Burgundian army.

Philip of Burgundy was the main sponsor of the Crusader army that would march overland to Hungary to assist King Sigismund. The crusade had been four years in the making and had suffered numerous leadership changes and schedule delays. Through special taxes, Philip raised 700,000 gold francs. His son, 24year-old Count John of Nevers, was picked, not surprisingly, to lead the Franco-Burgundian army.

It was impractical to await an attack by Bayezid, so the Crusaders’ strategy was to march into enemy-occupied Bulgaria to force Bayezid to give battle, notes Norman Housley in The Later Crusades.

All Latin crusades, including the 1396 crusade, had a major organizational weakness, which was that the Latin armies were composite forces, writes John France. This led to a lack of unity regarding the tactics to be used. In the case of the Battle of Nicopolis, dissension occurred at the most inopportune time imaginable: the arrival of Bayezid’s army to lift the Crusaders’ siege of Ottoman-held Nicopolis.

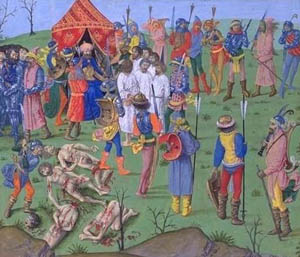

On the eve of the battle, King Sigismund submitted to the will of the overbearing French and Burgundian nobles. Rather than fighting a defensive battle as Sigismund would have preferred, the Crusader army would attack. The Franco-Burgundian troops formed the vanguard of the attack. On the morning of September 25, their heavily armored cavalry struck. That tactic had failed the French up to that point in their war with England.

The French and Burgundian nobles had no appreciation of what they were up against. The Ottoman army was unified, well led, and experienced. Nicopolis was a great victory for Bayezid and a catastrophic defeat for the Crusaders. Many a soldier who might have remained in France or Burgundy to fight the English in the early 15th century died in the Danube Valley that day.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments