By Flint Whitlock

When Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933, the world changed forever.

Not only was Hitler determined to pay back Germany’s enemies for his country’s defeat during the Great War, but he was also determined to rid Germany and the rest of Europe of persons whom his twisted Aryan ideology believed were “inferior” or “subhuman.”

Almost immediately upon assuming power, Hitler and his minions began instituting a policy of imprisoning personal and political opponents in special holding centers known as Konzentrazionlagern—concentration camps, or “KL” for short.

At first, abandoned factories, warehouses, and even castles were used to incarcerate the Nazis’ enemies—Communists, Social Democrats, dissidents, and anyone who dared to speak out against the government and its policies. Soon others were added to the list of prisoners—outspoken priests and pastors, men guilty of shirking work, even vagrants. The camps initially were to be “re-education centers,” where those who held anti-Nazi views would be taught how to think “correctly.”

The First Concentration Camps: Nohra and Dachau

The first camp built specifically to hold these persons was constructed in March 1933 at a small Luftwaffe airbase at Nohra, a tiny farming village near Weimar, in the rabidly pro-Nazi state of Thuringia. Consisting of just a few buildings that could hold only 250 prisoners, the camp was soon overflowing; a better and larger solution needed to be found.

SS head Heinrich Himmler directed SS General Theodor Eiche to devise a more capacious camp, which he did at Dachau, a Munich suburb. Here, adjacent to the sprawling SS compound, dozens of barracks sprang up, surrounded by an electrified barbed wire fence and a high wall to keep out the prying eyes of the neighbors. Here, too, were special facilities for the mistreatment of inmates, and a crematorium for the mass disposal of corpses that, given the harsh treatment and torture, the medical experiments on live subjects, the rampant diseases, and the starvation rations, were becoming more numerous by the day.

It was not long before Jews, Gypsies (also known as Sinti and Roma), Jehovah’s Witnesses, and others also found themselves being arrested without charge and transported to the growing number of camps. Using Eicke’s “Dachau model,” additional camps were created. By the time the war ended, there would be hundreds of main and subcamps, mostly slave-labor camps (Buchenwald, for example, had 174 subcamps).

It was also the concentration camp system that drew little protest from German citizens that emboldened the Nazi regime to go to the extreme and create the death camps—places of mass extermination, primarily but not exclusively of Jews.

Buchenwald, “Beech Forest”

In July 1937, the first buildings of Buchenwald began to be erected atop the Etterberg hill, which dominates the otherwise flat landscape around Weimar. Long a favorite spot for picnickers who enjoyed the views from the Bismarck Tower on the hill’s southern slope and the baroque stateliness of Anna Amelia’s palace on its northern side, the Etterberg held a special place in the hearts of the locals. Atop the hill, it was said, the great German poet and playright Goethe spent many hours beneath the shade of a towering oak tree composing some of his most famous works, including Faust.

For centuries Weimar was the cultural capital of Germany and had even been selected as the nation’s seat of government following the end of World War I. But Weimar was also a hotbed for right-wing radicals who hated the weak but democratic regime. It was perhaps inevitable, then, once Hitler took power, that the Etterberg hill would become a place to incarcerate enemies of the Nazi state.

The word “buchenwald” means “beech forest,” and the Etterberg was a heavily wooded place that abounded with wild game—a favorite hunting ground for generations of nobility.

Late on the morning of July 15, 1937, a convoy of trucks carrying 149 carpenters and other craftsmen—all of them political prisoners—came up the hill from Weimar; the men were immediately put to work by the SS construction chief.

Much work needed to be done. Over the years, Buchenwald’s inmates would be involved in grading the camp streets; laying water and sewage lines; and constructing barracks, latrines, administrative offices, guard towers, fences, storehouses, barracks for the guards, homes for the officers and administrators, garages, an indoor riding arena, theater, troop casino, dog kennels, falconry area, a zoo for SS families, an inmate infirmary and library, troop hospital, shooting ranges, depot for building materials, a brothel, and, most chillingly, a gatehouse with a sinister wing known as the Zellerbau or “bunker”—an inmates’ prison that contained a number of tiny cells where prisoners often would be tortured in the hours before their scheduled executions.

Villa Koch: The Life of the Commandant and his Wife

Buchenwald’s first commandant was an SS Standartenführer (Colonel) by the name of Karl Otto Koch. He had already impressed Himmler and the Nazi hierarchy in 1934, when he became commandant of Sachsenburg, a concentration camp located in an abandoned four-story textile mill near Chemnitz. There he caught Heinrich Himmler’s eye as someone unafraid to carry out even the most chilling orders. Between 1934 and 1937, Koch held a number of different posts at a variety of concentration camps, including Esterwegen (near Hamburg), Lichtenburg (in Prettin, near Wittenberg), and at Dachau. He then became commandant of the Gestapo’s notorious Columbia- haus prison and torture chamber near Berlin’s Tempelhof airport and at Oranienburg-Sachsenhausen, in a Berlin suburb. At these camps Koch learned how to bend men to his will and how to apply the most extreme forms of mental and physical torture, all the while gaining a reputation within the SS as a sadistic, ambitious administrator, unrestrained by a moral compass or human decency. He surrounded himself with like-minded lieutenants and a like-minded wife.

In 1936, while commandant of the Sachsenhausen camp, Koch met 30-year-old Margarete Ilse Köhler, a secretary at the Reetsma Cigarette Company in Dresden. Not a great deal is known about her early life or the circumstances of her meeting Koch. What is known is that she was born in Dresden to Eduard and Anna Köhler on September 22, 1906, preferred to be called Ilse, and avoided high school but instead attended a trade school, where she acquired stenographic and secretarial skills; her first job, in 1922, was as an apprentice in a book store. She joined the Nazi Party in 1932 (party membership number 1,130,836)—one of the very first women to do so.

Fascinated by uniforms, the red-haired Ilse exclusively dated members of the SS and SA, so it was only natural that she fell in love with a grandly uniformed SS colonel, even though he was round-faced, balding, stocky, nine years her senior, and divorced with two sons. After a courtship lasting a few months, she and Koch, whose star was on the rise within the strange world of concentration camp administrators, were married on May 25, 1937, in a traditional SS wedding ceremony with all the ritualistic trimmings. She would bear him three children. In August 1937, the Kochs moved from Sachsenhausen into new quarters at Buchenwald, where he set up his practice of sadism and brutality, the likes of which, he was sure, would delight his superiors and, at the same time, enrich his own bank account.

While the prisoners at Buchenwald were brutalized, starved, and made to live in squalor, the Kochs lived in high splendor at Villa Koch. Their cellar was full of wine and foodstuffs. They also took frequent vacations and ski trips. Karl used every opportunity to embezzle from the camp and the prisoners to enrich himself. Parties and orgies, too, were often held at Villa Koch in which alcohol flowed abundantly and marital fidelity was forgotten by both Ilse and Karl and others in attendance.

The Witch and the Hangman of Buchenwald

Ilse Koch was, initially, one of seven SS officers’ wives at Buchenwald, but she was not the type who made friends easily. By all accounts, Frau Koch who, from later photographs, can best be described as “dumpy,” was vain, cruel, cold-blooded, sadistic, degenerate, and power hungry—even more so than her husband. Some reports even characterize her as nymphomaniacal. Many other labels were pinned on her: the “Commandeuse of Buchenwald,” the “Witch of Buchenwald,” and, most alliteratively, the “Bitch of Buchenwald.” Despite her later denials to the contrary at her war crimes trial, Ilse Koch seems to have involved herself in many aspects of the day-to-day operation of the camp, including selecting tattooed prisoners to be killed and their decorated skin made into gruesome household objects such as lampshades and photo album covers. The matter of tattooed prisoners and the use of that skin is one that will be forever linked with Buchenwald and Frau Koch.

Kurt Sitte, a German physician who was imprisoned atop the Etterberg, told a postwar U.S. Senate subcommittee that he had been detailed to work in the pathological department and was well acquainted with the matter of tattooed inmates. He said, “Tattooing for our collection had to be colorful, not in other ways particularly interesting; but we had to have stocks of this material. There were many visitors the SS brought to the camp, and they used to be thrilled when they saw these skins in the pathology department among the other exhibits. Therefore, we always had to have a hundred or so of these tattoos in our collections, and among them, if possible, many of the obscene motifs.

“I do not think there is anything fascinating [about tattooed skin] for a normal functioning brain; though, it was fascinating for these people, the SS. Our SS officers and guards always wanted to see these skins when they came to the pathology department. Frequently they brought visitors to the camp, led them around, and we had to explain what we were doing; how the skins were made, and they always stayed long with this collection.”

Dr. Sitte was convinced that the SS’s interest in tattooed skin was strictly for ornamental, not scientific, reasons. “You would not need hundreds and hundreds of such skins for research purposes,” he told the senators.

Koch’s underlings were just as cruel as their master. One of them was the camp’s chief jailer, 23-year-old Hauptscharführer (master sergeant) Gerhard Martin Sommer, who had previously served under Koch at Sachsenhausen.

Sommer had a favorite torture—tying prisoners’ wrists together behind their backs and then hanging them a few inches off the ground from cell bars, stanchions, or the limbs of trees until their arms became dislocated. This punishment earned him the nickname “the Hangman of Buchenwald.” When this particular form of punishment was carried out against groups of prisoners in the woods around the camp, the screams of the unfortunates were so intense that the other inmates soon gave the sound a name—the “singing forest.”

Among all the sadists at Buchenwald, and there were countless numbers, no one could approach Sommer in terms of cruelty. His office in the camp jail, known as the bunker, held various instruments of torture that would have seemed appropriate during the Spanish Inquisition, along with instruments of death—needles he used to inject air and carbolic acid into the veins of his victims.

Sommer seems to have had a special dislike for clergymen and went out of his way to abuse them on the slightest excuse, or even none at all. For example, after learning that an inmate priest had heard another Catholic’s confession, he beat the priest to death.

Slave Labor and Atrocities

If Sommer had a rival for the title of most hated and feared, it was the camp adjutant—an Obersturmführer (First Lieutenant) named Heinrich Hackmann. As Koch’s right-hand man, Hackmann was given free rein to personally administer any type of punishment he wanted on any inmate for any reason.

The stories told of Hackmann’s cruelty are legion. On one occasion, he noticed spittle on the ground, a violation of one of Koch’s sacred rules, and forced the nearest inmate to lick it up. Hackmann was especially fond of pouncing on inmates during roll call and punching them or striking them savagely with a leather whip he constantly carried.

At times the entire camp was made to witness beatings and hangings. For beatings, a special wooden table known as a bock was used, and for hangings a portable gallows, with ropes enough for five, was set up near the gatehouse. Such demonstrations told the inmates that even petty violations of camp rules would be met with the harshest punishment.

The Nazis learned early on that prisoners needed to be kept busy at hard labor in order to prevent rebellions and escapes, and soon a granite quarry was opened at Buchenwald in which almost the entire inmate population was set to work. The backbreaking labor of chopping blocks of stone was hard enough, but the SS guards and their Kapo assistants (ordinary prisoners, mostly hardened criminals, made into supervisors and given power over the other inmates) were not content with simply working the inmates to exhaustion. Many a poor soul was whipped or beaten when he could not work fast enough to please his overseers, and deaths occurred daily in the quarry—some accidental, some intentional.

Tales are told of heavy carts full of rocks being pushed up a steeply graded track only to be pushed back down at breakneck speed until they derailed or crashed into inmates working at the bottom, or of prisoners being shot or pushed off the lip of the quarry, or of prisoners being held in the branches of a bent sapling at the surface, which was then allowed to spring upright like a catapult, launching the helpless man to his death on the rocks below.

In time, two factories were built at Buchenwald to supplement the work that was going on in the quarry—work that never ceased. One was known as Deutsche Ausrüstungswerke GmbH (German Military Equipment Works, Inc., abbreviated DAW, an SS-run enterprise formed in 1939), which made rifles, panzerFausts (antitank rocket launchers), and other weapons, while the other, which opened in early 1943, was created for the assembly of gyroscopes intended to be installed in Wernher von Braun’s V-2 rockets. The rocket-testing facility at Peenemunde and the underground manufacturing works at Nordhausen, along with a camp known as Mittelbau-Dora, all made extensive use of slave labor from Buchenwald. Inmates from the camp were also drafted to work in various other German industries, including the Krupp steel works in Essen.

Experimentation on the Prisoners

In 1943, Buchenwald, along with many of the other camps, became a site for gruesome medical experiments conducted on live patients by Nazi doctors. Poisons were tested on live subjects, as were various pathogens such as typhus. Some inmates were intentionally wounded and their injuries allowed to become infected so that various types of treatment could be tried on them.

If the victims did not die during the experiments, they were killed so that their bodies could be autopsied. The internal organs of some of the victims from these experiments were preserved in jars at Buchenwald’s pathology department in the “name of science.”

One of the major problems within the concentration camps was endemic typhus, a louse-borne disease that not only affected the prisoners but could easily spread to the guards, administrators, and the nearby civilian population. Shortly after the camp was opened, a large tank of delousing solution was installed. Whenever a transport of new prisoners arrived, they were ordered to strip naked and line up to have all their body hair shorn. The hair was collected and used for stuffing mattresses.

One prisoner at Buchenwald recounted the barbering ritual: “My barber started by placing clippers on my forehead and running them to the base of my neck. Five strokes and the job was done…. With dull clippers, underarm, genital, and anal hair were also removed, leaving us nicked and bleeding. From here we were led to a pool filled with creosote and ordered to get in. I groaned with pain; every nick and cut stung like hell.”

Life in the Buchenwald Camp

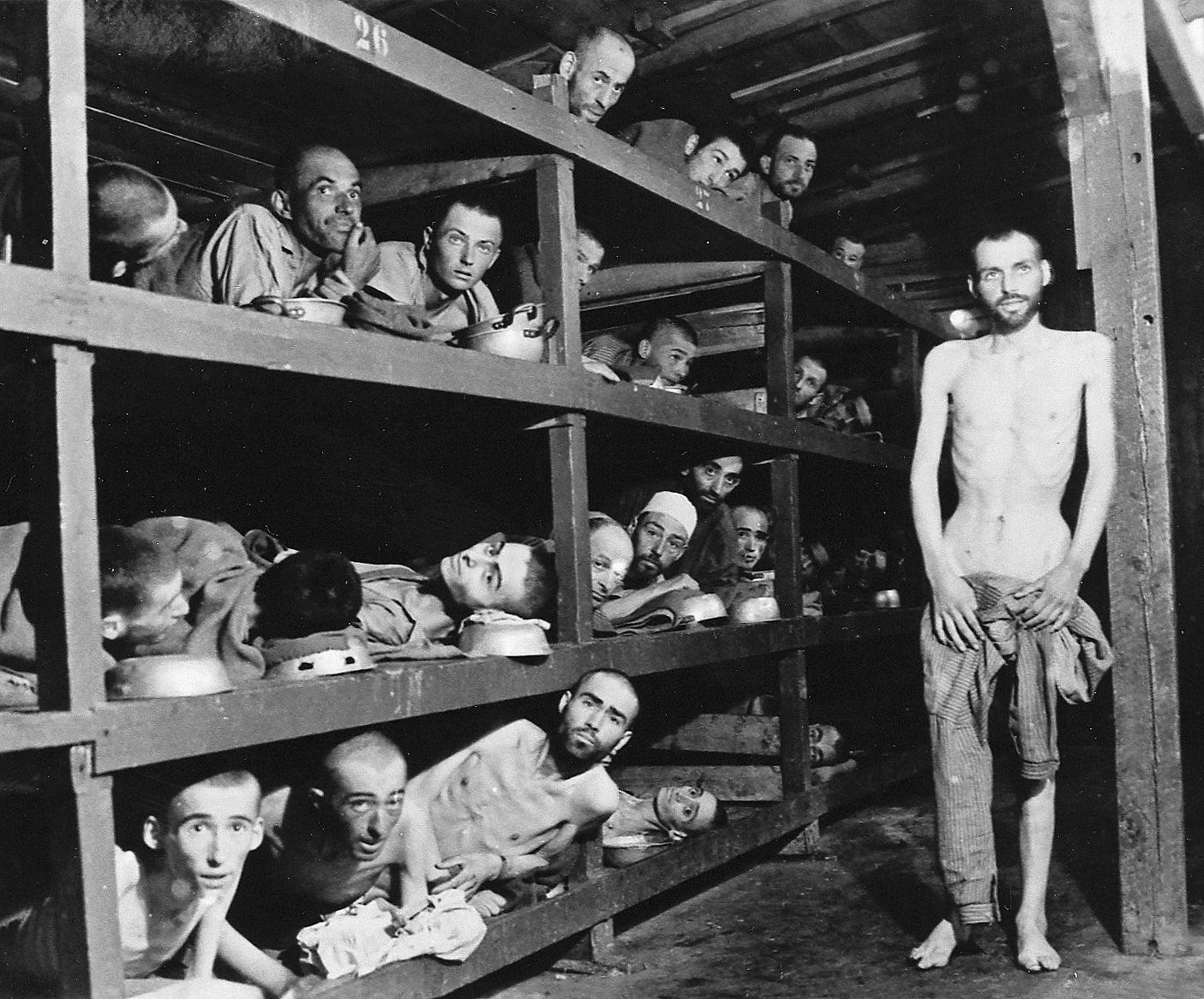

A typical day in the life of a Buchenwald inmate began at, or before, dawn when the prisoners were rousted out of their bunks with shouts from their barracks chiefs known as Blockälteste. The inmates scrambled to the latrine and washroom, where they were allotted only a few minutes to take care of their personal business. There, a pitifully weak stream of cold water was all the men could use to wet their faces and perhaps splash onto their stinking bodies.

Once the morning ablution was finished, it was off to the mess hall, where thousands of famished men, their stomachs growling audibly, fought over the meager scraps of food provided to them by their masters. It was a stretch to even call it food, for rarely was it fit to feed even barnyard animals. One small loaf of sawdust laced bread might be divided among five or more men, each one thinking the man next to him received a slightly larger slice than did he; fights over a scrap of bread broke out often. A lukewarm cup of ersatz coffee or tea and a bowl of thin, nearly inedible soup usually made from grass and turnips was ladled out. On rare occasions, if the SS men were feeling generous, there might be a small piece of sausage, which was often rotten and made from “condemned” meat.

The inmates then rushed back to their barracks to sweep them clean and ensure that every bed was made and every bunk was perfectly aligned. If anyone had defecated in his bed during the night (a not-uncommon occurrence, given the high incidence of dysentery), the bed had to be scrubbed clean. And if so much as one piece of straw was found on the floor or one bunk was out of alignment, beatings by the Kapos would be meted out to the innocent and guilty alike.

Roll Call at the Camp

Then the entire population of each barracks double-timed to the Appellplatz, or roll-call square, adjacent to the main gate, running a gauntlet of Kapos and guards with rubber hoses who lashed out at them as they dashed past. Anyone who tripped and fell to the ground was subjected to a real beating. Guards with weapons at the ready watched over the square from their towers.

Roll call was a twice daily exercise in terror and intimidation. At the Appellplatz, where inmates from all of the barracks were gathering, prisoners too weak or ill to run were carried by their blockmates, and it was common for the SS man in charge of the roll call to beat any inmates claiming to be sick. Inmates too ill to work (and an inmate needed to be near death to be excused from work details) reported to the infirmary, a place of horror from which very few inmates ever returned alive.

There was always much pushing and shoving by the Kapos and their assistants to align the rows perfectly, just the way the SS liked them. Every man had to stand stiffly at attention and look straight ahead, his fingers straight, his thumbs lined up with the seams of his trousers, no matter if the day was warm and sunny, windy or rainy, or if it was freezing and snowing fiercely. Anyone who moved, coughed, sneezed, talked, urinated, or collapsed from the ordeal was beaten savagely.

From loudspeakers came the command “Mutze … ab!” (Caps off). The prisoners had to whip off their striped cotton caps with military precision and hold them against their right pant leg. Anyone slow in obeying the order could count on a beating with rubber hoses by the Kapos. The next order—“Mutze…auf!” (Caps on)—was similarly scrutinized. Again, slowness in executing the command would bring verbal and physical harassment.

As getting thousands of persons to perform this cap-off, cap-on maneuver with military precision was virtually impossible, it was repeated over and over again until everyone—thousands of sick, starved, and brutalized men—performed in unison, like a well-rehearsed drill team.

SS sergeants then counted the men assembled from each barracks. When the counting was finished, the scraps of paper on which the numbers had been written were gathered up and taken to the gatehouse, where SS men added up the numbers. Only during this time were the prisoners allowed to relax from their rigid postures. At this point the inmates were told to stand easy.

If the numbers were not correct, and seldom were they correct on the first count, the roll was retaken. This process, in every type of weather, normally took hours. The camp administration had a fetish for accuracy. If anyone died during the night, that person’s corpse had to be present as well, for no one was allowed to be officially declared dead until after the evening roll call.

Hunger and Slavery

After the morning counting, announcements, beatings, and hangings were concluded, the assembled group quickly broke down into their work groups, or Arbeitskommando, to begin another 12-hour day of deadly, backbreaking labor. Some prisoners worked in the quarry or on construction projects, others at administrative duties, while still others performed groundskeeping tasks. Other Kommando headed off to the laundry or the sanitation detail to clean out the latrines or the crematorium or infirmary or to work on a road-building project, or to their jobs as servants within SS households, or to some other make-work project the SS had dreamed up to keep the prisoners occupied and degraded.

At noon, work stopped for 30 minutes for lunch. The noon meal usually consisted of ersatz coffee or tea and a watery bowl of soup flavored with grass, turnip greens, or decaying vegetables. Then it was back to work until evening.

And so it went—first at Dachau, and then at all the other camps—the daily, dehumanizing routine never varying, a process that not only turned the inmates into automatons but also made it possible for the SS to regard the prisoners as less than human and thus permit the guards and administrators to mistreat them without feeling guilt or compassion.

At the end of the day, all prisoners were required once again to report to the Appellplatz and submit to another long, mind-numbing roll call. Once evening roll call was concluded, the prisoners were marched off to dinner. The evening meal was again the odd soup and perhaps some sort of salad made of moldy greens. Occasionally, as a form of group punishment for the transgressions of a few, the entire prisoner population of the camp would go without any food for an entire day.

Hunger reigned supreme. Romek Wajsman, 14 years old when he was locked up in Buchenwald, spoke for everyone when he said, “In the camps we used to fantasize of having enough bread and butter.”

Because word of Koch’s embezzlements and other administrative irregularities at Buchenwald (not connected with the mistreatment of prisoners) had reached higher ranks, Karl Otto Koch was secretly investigated by the SS. He was transferred to a new camp, Majdanek, near Lublin, Poland, in September 1941, but after only a few months he was arrested by the SS and placed on trial. Found guilty, he was imprisoned and was eventually shot by an SS firing squad at Buchenwald on April 4, 1945.

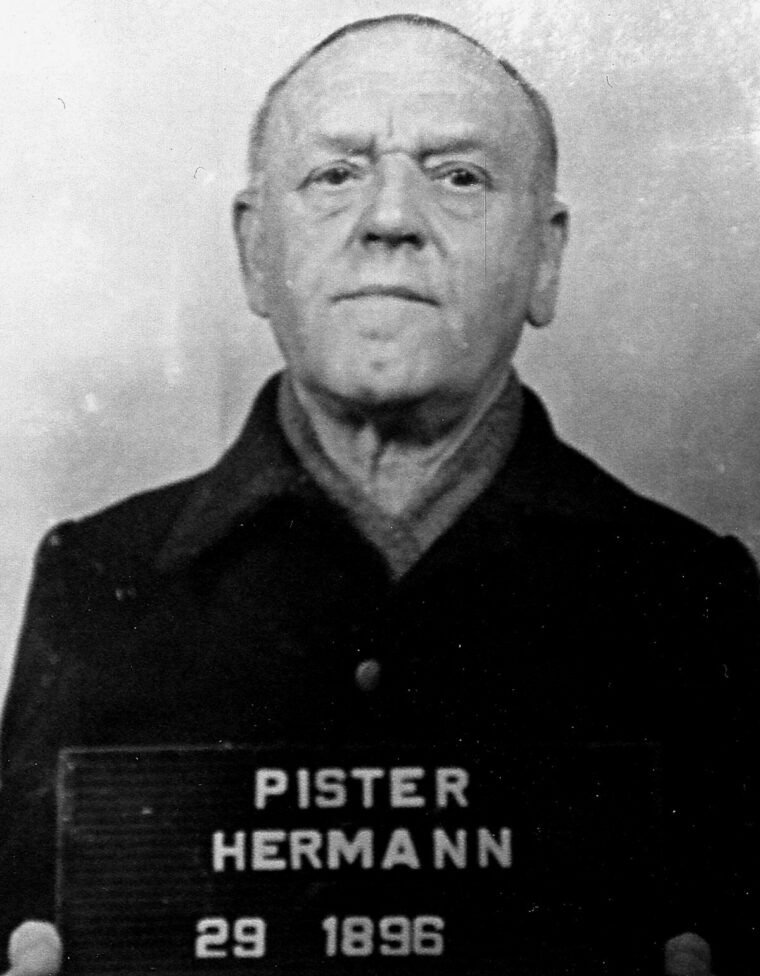

On December 20, 1941, a new administrator arrived to take command of Buchenwald, 56-year-old Oberführer (Senior Colonel) Hermann Pister. Although Pister was just as hard as Koch, he was not the sadist his predecessor had been. Life for the inmates continued to be difficult, however, and thousands continued to die from disease, starvation, and overwork.

The VIP Political Prisoners of Buchenwald

Buchenwald was almost exclusively a camp for men and boys; only a handful of women were ever held there. One of the few was Princess Mafalda Maria Elisabetta Anna Romana of Savoy, one of the daughters of Italian King Victor Emmanuel III. Her husband, Philipp of Hesse, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel, was a German nobleman and Hitler’s art agent in Italy. But, as Hitler pressured Mussolini to crack down on the Italian Jews and ship them to the death camps in Poland, Mafalda became more vocal in her opposition to the Hitler regime, causing her husband to fall out of favor with the Nazis. Believing she was working against him, Hitler made plans to do away with Mafalda, calling her “the blackest carrion in the Italian royal house.” In September 1943, she was arrested and sent to Buchenwald, where she lived in one of the VIP homes outside the barbed wire.

Princess Mafalda was not the only politically important prisoner at Buchenwald. An area known as the Fichtenhain Special Camp and its adjacent isolation barrack located between the SS barracks and the Gustloff-Werk II also held a variety of men, women, and children who were not allowed to mingle with the general concentration camp population.

French politicians, especially, were “guests” of the Nazis at Buchenwald. Léon Blum, a Jew and the former premier of the French Popular Front government from 1936 to 1938, was imprisoned here after the French Free Zone was occupied by the Germans in November 1942, following the Allied invasion of North Africa. Other members of the French government held at KL Buchenwald included Édouard Daladier (prime minister in 1940); Georges Mandel (the last minister of the interior before the fall of France in 1940); and General Maurice Gamelin (commander in chief of French and British forces in 1940). Also incarcerated atop the Etterberg were Reserve Division General Andre Challe and his son; Professor Alfred Balachowsky, director of the Pasteur Institute; and a Mssr. Clin, director of the National Library of France.

Here also was kept Dr. Rudolph Breitscheid, former chairman of the German Social Democrat Party, and his wife. In the cellar of one of the SS troop barracks was a special row of cells known as the SS detention area, where the Protestant theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer was kept. Later evacuated to Flossenbürg, Bonhoeffer was hanged on April 9, 1945, just days before the camp was liberated.

KL Buchenwald did not discriminate when it came to the nationalities of its prisoners. Buchenwald also held as inmates Anton Falkenberg, head of the Copenhagen police; Petr Zenkl, the former mayor of Prague; British Wing Commander Forest Yeo-Thomas; and a former prime minister of Belgium, Paul-Emile Janson, who died at Buchenwald in 1944.

The Children and Families of Buchenwald

The Nazis were particularly hostile toward writers and intellectuals who did not toe the Nazi Party line—even if they were foreigners. Leon Jouhaux, recipient of a Nobel Prize in literature, was imprisoned at Buchenwald, as were other French writers, including Jean Améry and Robert Antelme. Held, too, were the German author Ernst Wiechert; Ernst Thälmann, the leader of the KPD (German Communist Party); and Curt Herzstark, an Austrian and the father of the pocket calculator. Konrad Adenauer, the former mayor of Cologne, was also jailed atop the Etterberg; he would be the first postwar chancellor of West Germany. Two children who would grow up to be famous authors—Elie Wiesel and the Hungarian Imre Kertész—were also inmates at Buchenwald.

Other formerly prominent individuals who spent time at Buchenwald included General Friedrich von Rabenau, implicated in Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg’s July 20, 1944, attempt to kill Hitler (von Rabenau was executed April 15, 1945, at Flossenbürg). Also included in custody was the wife of Generaloberst (Colonel General) Franz Halder, Hitler’s former chief of the general staff, suspected of involvement in the plot. Halder himself was arrested and later held at Flossenbürg and Dachau.

When the Nazis could not arrest their enemies, they often arrested the family members of their enemies. Ten members of von Stauffenberg’s family were held in the isolation barracks, as were industrialist-turned-Hitler-opponent Fritz Thyssen and his wife. Also jailed was the sister of anti-Hitler German diplomat Hans Bernd Gisevius, who had been involved in the July 20 plot and had fled Germany for Switzerland.

POWs at Buchenwald

Although Buchenwald was not a POW camp, from time to time captured enemy soldiers were held there. After the July 1941 German invasion of the Soviet Union, approximately 7,000 Soviet POWs were incarcerated at Buchenwald—and virtually all of them were executed.

In 1944, the Germans had captured a group of 37 British and French SOE (Special Operations Executive—the British equivalent of the U.S. Office of Strategic Services, or OSS) operatives and confined them in Buchenwald. Accusing them of being spies, the Germans hanged 17 of them.

A group of 168 Allied airmen was also held at Buchenwald. One of them, a Royal Canadian Air Force bombardier named Art Kinnis, shot down over France on July 8, 1944, recalled, “We knew that our group must become very united and that we must make sure that the powers that be realize that we are all aircrew of the Allies, and that what is now happening to us is against the Geneva Convention.”

The Canadian also recalled that life at Buchenwald was not all suffering; the one bright spot was music. Kinnis said that one of his most pleasant surprises was hearing the camp’s symphony orchestra and jazz band playing English and American pieces. “Music is one language that requires no translator, and the evenings we spent listening to some very highly rated [European musicians] were exceedingly pleasant. The conductor had the reputation of playing before royalty, before his capture. How we loved to hear his rendering of ‘Tales from the Vienna Woods’ or ‘Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring,’ and many other lovely creations. A Russian choir there was as good as you could hear anywhere. The mere fact that you could not understand one word drifted into the background, as one was carried into the world of music. This little haven of sound was possibly the only pleasant side of Buchenwald.”

The intervention by a Luftwaffe general in October 1944 enabled the Allied airmen to be transferred to Stalag Luft III, near Sagan, Poland, after two months at Buchenwald.

The Goethe Oak Burns

However, while the Allied flyers were still at Buchenwald the American Air Force mounted the only bombing raid of the war against the camp—actually against the Gustloff-Werk II—on August 24, 1944. So successful was the raid that the entire factory was obliterated and production of the V-2 gyroscopes was halted. Unfortunately, many inmates working in the factory, along with their overseers and guards, also perished, as did SS family members living in quarters nearby. Princess Mafalda, too, was one of the victims of the air raid. The home in which she was being held collapsed upon her and, despite the efforts of SS doctors to save her, she succumbed to her injuries.

Perhaps the most symbolically important damage was done to the Goethe Oak. An incendiary bomb had set it alight, and it was later cut down. An old German prophecy said that the nation would exist as long as the Goethe Oak stood.

Discovering the Camps

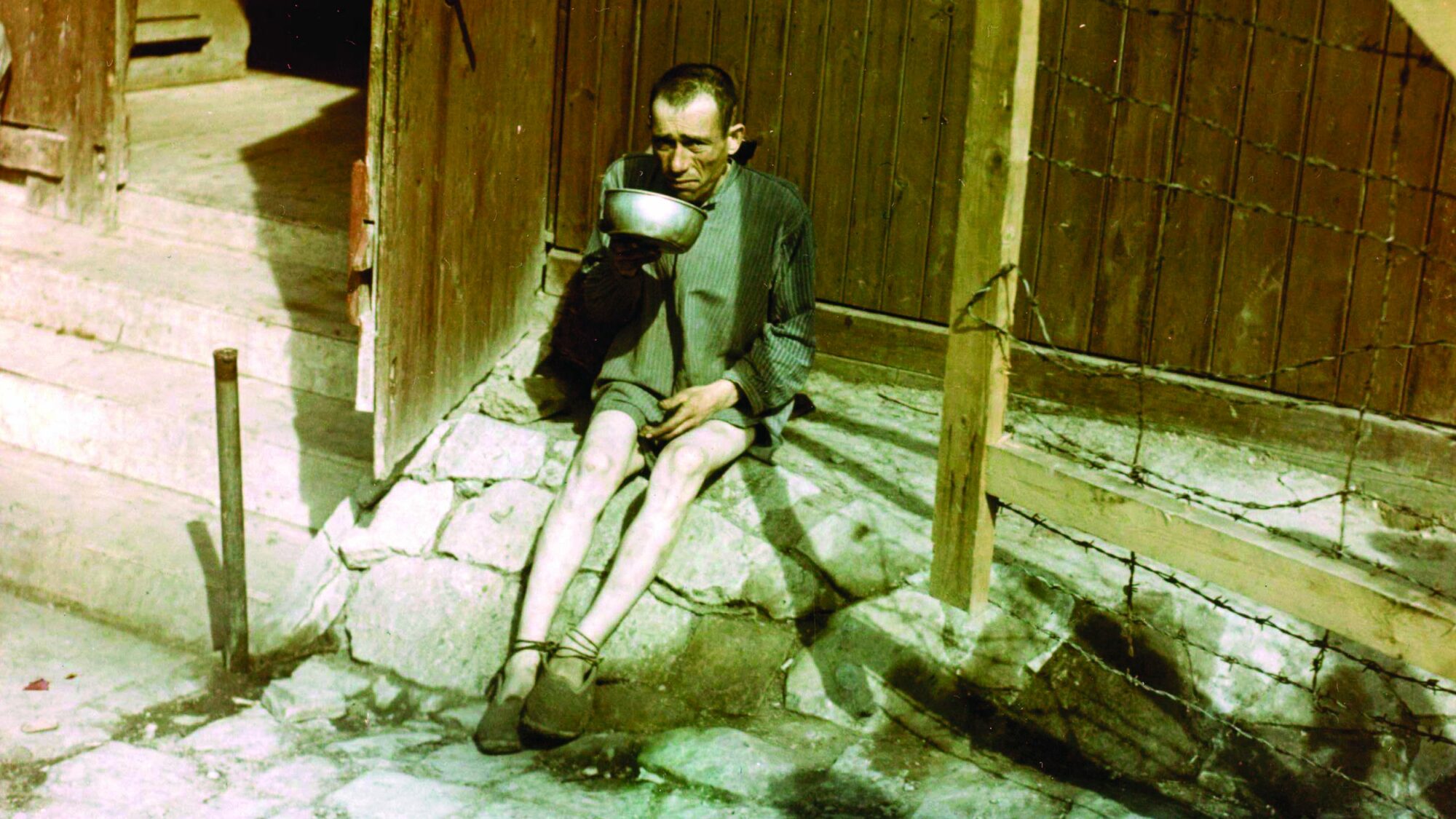

As the war continued to go badly for the Germans, more and more inmates from camps in the East (including Auschwitz) that were threatened by the approach of Soviet armies were shipped to Buchenwald. Soon the camp atop the Etterberg was bulging with thousands of additional prisoners. The primitive, already overworked sewage system was pushed beyond capacity, and the meager rations became even more meager. Disease was rampant, and the camp had gone well beyond what might be called a humanitarian crisis. Still, the trains full of sick and starving prisoners, now mostly Jews, continued to arrive daily at Buchenwald’s railroad yard.

In early 1945, the war was quickly coming to an end for Nazi Germany, but Buchenwald continued to overflow with thousands more inmates from other camps. Himmler, hoping to save his own skin, sent directives to the various camps, telling the commandants to open the gates and send the prisoners on death marches into the countryside.

General George S. Patton’s U.S. Third Army was approaching from the west but, almost incredibly, neither Patton, General Omar N. Bradley (commanding the U.S. Twelfth Army Group), nor Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower, was aware of the existence of the death and concentration camps; no camp was marked on the military maps the Allies were using. And, although American newspapers had regularly reported on the atrocities committed against Jews and other “undesirables” in Europe since 1933, no plans or training had been instituted by the U.S. Army to prepare the GIs and their officers for what to do in the event a camp was discovered. As a result, the Americans closing in on the camps were totally unprepared for what they found in April 1945.

The first camp uncovered by the Americans was Ohrdruf, a slave labor camp stocked with inmates from Buchenwald, 30 miles west of Buchenwald. Brig. Gen. William M. Hoge, the 4th Armored Division’s commanding officer, had split his command and sent Combat Command B (CCB) to the city of Gotha and Combat Command A to Ohrdruf. The 355th Infantry Regimental Combat Team of the 89th Infantry Division was attached to CCB.

On April 4, 1945, the 4th’s CCB and the 89th’s 355th Infantry broke through the gates of the Ohrdruf camp and discovered a horrific scene almost beyond description: thousands of dead, nude, and emaciated bodies scattered around the camp, each one showing signs that he had been shot at close range. In some of the foul barracks GIs also discovered hundreds of sick inmates on the verge of death. A funeral pyre with the charred remains of uncountable numbers of victims smoldered nearby. The rest of the inmates had been marched back to Buchenwald at the approach of the Americans.

The Buchenwald Revolt

Higher headquarters was quickly informed, and Patton, Bradley, and Eisenhower would tour the camp and witness its horrors firsthand on April 13, their jaws firmly set in anger. Bradley wrote in his memoirs, A Soldier’s Story, “Third Army had overrun Ohrdruf … and George [Patton] insisted we view it. ‘You’ll never believe how bastardly these Krauts can be,’ he said, ‘until you’ve seen this pesthole yourself.’”

In his 1948 best-selling memoir, Eisenhower wrote, “I saw my first horror camp. It was near the town of Gotha. I have never felt able to describe my emotional reactions when I first came face to face with indisputable evidence of Nazi brutality and ruthless disregard of every shred of decency. Up to that time I had known about it only generally or through secondary sources. I am certain, however, that I have never at any other time experienced an equal sense of shock.”

But on April 4, the existence of Buchenwald was still unknown to the Americans about to stumble across it. A week later, the southern column of Combat Team 9, the advance element of Maj. Gen. Robert W. Grow’s 6th Armored Division, ran into enemy resistance at the village of Hottelstedt, about two miles northwest of Buchenwald.

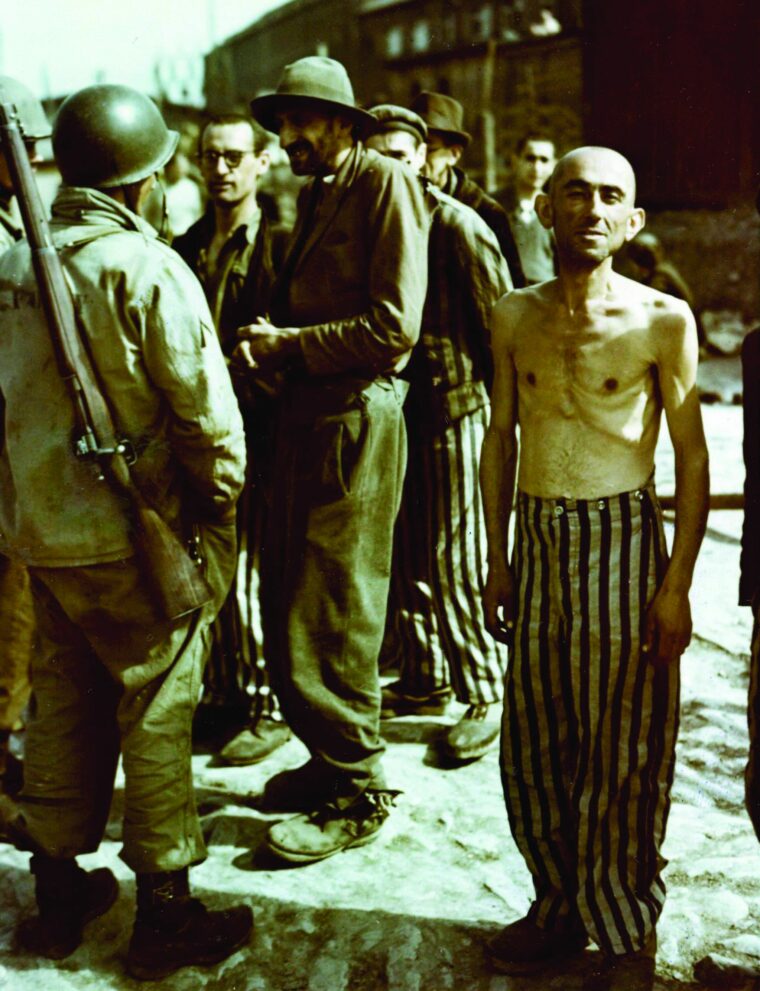

As the brief firefight ended, the GIs were astounded to see a group of emaciated men in striped uniforms coming down the road from the direction of a heavily forested hilltop, waving their arms wildly and jabbering in a strange tongue.

When the men could be calmed down and an interpreter found someone who could speak Russian, the Yanks heard a fantastic tale—tens of thousands of political prisoners were just up the road at a terrible place known as Buchenwald. After the sounds of battle emanating from Hottelstedt had been heard, said the Russians, a secret resistance group inside the camp had revolted against their guards and taken over the camp.

Bringing American Supplies to Buchenwald

Captain Robert J. Bennett, commanding the southern column, sent the battalion intelligence officer, Captain Frederic Keffer, ahead in an M-8 armored car along with three men (one of whom was fluent in German) to scout the situation. Several of the Russians rode along atop the M-8 to guide the Americans to the camp.

Clearing the screen of trees, Keffer and his party came across an astonishing sight, a huge camp with scores of barracks and thousands of men, all of them skeletal in appearance and some armed with German weapons, behind a barbed wire enclosure. A wild cheer of joy greeted Keffer and his German-speaking sergeant as they entered the encampment.

Suddenly, Keffer found himself lifted off the ground by a score of hands and carried around “on the shoulders of the crowd like a conquering hero.” Keffer said, “What an incredible greeting that was. I was picked up by arms and legs, thrown in the air, caught, thrown again, caught, thrown, etc., until I had to stop it, I was getting so dizzy. How the men found such a surge of strength in their emaciated condition was one of those bodily wonders in which the spirit sometimes overcomes all weaknesses of the flesh. It was a great day!”

Keffer was pulled and pushed through the crowd toward a building where he met some of the leaders of the prison underground who were now in control. “I told them I would radio for medical help and for food, and I requested them not to let the former prisoners, if they could help it, wander far outside the camp and possibly unwittingly interfere with our military progress. Then I managed somehow to return to the scout car, give all the food we had to the camp, and drive back to our main column [at Hottelstedt].” At 5:35 pm, the Yanks left Buchenwald; the camp was now under the complete and sole control of the inmates.

Returning to Hottelstedt, Keffer told Bennett what he had found and requested that food, water, and medical help be dispatched to the camp as soon as possible. Bennett radioed higher headquarters of the discovery of Buchenwald. The electrifying news that 21,000 sick and starving prisoners were still alive atop the Etterberg (some 24,000 had been evacuated a few days earlier and either put on trains to other camps or sent on death marches to wander the countryside) but needed an enormous amount of help—and quickly—was passed up the line. In short order, mobile hospitals and field kitchens were dispatched to Buchenwald.

“We Expected to Defend Ourselves”

The prisoners at Buchenwald had been waiting years for this day. A secret “international committee,” headed mostly by incarcerated communists from several nations, had squirreled away weapons made from parts stolen from the on-site armaments factory or purchased clandestinely from bribed guards. The overriding fear was that, once the SS knew that the Allies were about to uncover Buchenwald, they would massacre all of the inmates.

A former prisoner noted, “Only a limited number of inmates were aware of the planned uprising, but the SS, in some way or another, had learned of the existence of the camp’s ‘underground.’ However, they were never able to find out who the leaders or members of the underground were.”

One of the inmates, Max Feuer, recalled that the prisoners had been arming themselves since 1943. “We expected to defend ourselves,” he said. “We counted now that the guards will try to exterminate the camp. For this moment we were prepared to fight the guards.”

When firing was heard in the direction of Hottelstedt, the leaders of the international committee knew that the Americans were nearby and sprang into action; weapons were handed out (in addition to their smuggled weapons, the now-free inmates broke into the guards’ armory and grabbed 1,500 rifles, 18 light machine guns, four heavy machine guns, and 180 PanzerFaust antitank weapons) and rushed to their preassigned stations around the camp.

A very brief firefight, lasting no more than 15 minutes, broke out between guards and armed inmates. Most of the guards fled with inmates in pursuit. One hundred and twenty guards and other personnel were rounded up that day and brought back to the camp, where they were kept under armed guard in a barracks. They were later turned over to the Americans.

One of the inmates, a French teenager named Robert Max Widerman (he would later change his name to Robert Clary and be one of the stars of Hogan’s Heroes, a television situation comedy set in a World War II POW camp), who had already been in Auschwitz and Gross-Rosen, recalled the day of liberation: “We tore off our shirts and waved them…. Inmates hugged each other, jumping up and down, dancing, laughing with tears running down their cheeks, and shouting with incredible joy. Those too ill and weak could only smile; they understood what was happening. It was almost impossible to fathom that this day had actually arrived, that our miseries had come to an end, that we had survived.”

After the arrival of the Americans, the heavy mantle of death had been lifted off the camp as if by magic, transfiguring the grim, monochromatic landscape into a bright and hopeful vision. Robert Max Widerman noted, “Flags from all European nations had appeared, flying from the tops of the barracks. The whole camp took on a different tone. There was constant laughter, mixed with the eerie feeling we had of believing without believing what had just happened to us. The GIs [later] distributed food—things we hadn’t seen for years, and in large quantity. The tragedy is that many survivors died from overeating food too rich for them after such a long time of starvation.”

Over the next few days, as medical teams worked to stabilize the survivors, streams of GIs visited the camp and could not comprehend what they saw.

Allied Ignorance of the Camps: “It Came Out of the Blue”

It is curious that American soldiers and officers have professed a definite lack of knowledge of the camps and the persecutions that had been taking place in Europe since 1933. None of the officers or men of the advancing American units in 1945 apparently knew anything about the Nazi concentration camps they would soon encounter. As a consequence, the soldiers were completely unprepared psychologically for the experiences that would haunt them for the rest of their lives.

In the writings of the generals and statements of those GIs who came across the camps it appears that all were ignorant as to what was happening in the camps they uncovered. For example, although he recalled reading countless newspaper stories about the Nazi persecution of the Jews, Captain Mel Rappaport, 6th Armored Division, who arrived at Buchenwald on or about April 16, insisted that neither he nor the Army “knew in advance about the concentration camps, the killing centers, the gas chambers, the ovens, the hanging bars, the shooting grounds, etc. The big brass hats never told us that we would someday overrun these camps. Not even Patton knew.”

Merrill C. Burgstahler, an enlisted man with the 6th, also claimed no prior knowledge of the atrocities that were being committed. “It came out of the blue,” he said.

The reason why most soldiers have professed an ignorance of the persecutions being heaped upon the Jews of Europe may seem puzzling at first, but the answer may be quite simple. Millions of young men who may have been accustomed to reading a daily newspaper in their hometowns were suddenly plucked, either by the draft boards or by their own enlistment, from their homes and transported hundreds or thousands of miles away to a military base. A young man from, say, Brooklyn, who regularly read The New York Times, might have found himself in 1942 or 1943 at some backwater Army installation where The New York Times was not sold. The local newspaper likely did not carry many stories about the treatment of European Jews and, in any case, the average soldier, even if he had been aware of the situation overseas before entering the military, was too busy with his training duties and too concerned about his upcoming deployment to a combat zone to spend much time reading newspapers and attempting to educate himself on the larger picture and the plight of others. His primary focus was on preparing himself for battle.

Furthermore, there is no evidence that the average American soldier received any official Army instruction, either in basic training, advanced infantry training, or at briefings in the field once deployed to the European combat zone that would have educated him about concentration camps or readied him for the possibility of encountering such places. Members of specialized military government units were schooled in how to govern towns and cities captured from the enemy and how to deal with large numbers of civilian refugees but not concentration camps and concentration camp inmates. And, although the average American soldier was issued numerous training and field manuals on scores of subjects, there were no manuals that told him what to expect or how to conduct himself if he should unexpectedly encounter a camp filled with tens of thousands of sick and starving persons, or mountains of skeletal corpses that had been systematically slaughtered.

Even the acclaimed documentary film series Why We Fight by Frank Capra, which was shown to all U.S. Army inductees as indoctrination, did not dwell on the plight of European Jewry. In fact, in the entire seven hours of film, the Jews are mentioned only once. In the first film, Prelude to War, over a montage of images of churches and a synagogue, the announcer intones, “Thousands of other men of God—Protestant, Catholic, Jewish—were persecuted, arrested, confined in concentration camps.” The scene takes less than 15 seconds—15 seconds out of seven hours. There is not a single mention of Kristallnacht, ghettos, persecutions, medical experiments, gas chambers, or any explanation of what the narrator’s offhand reference to “concentration camps” meant.

It is no wonder, then, that the average American soldier in 1945 was totally at a loss when he came face to face with the shocking reality of the camps.

Showing the Atrocities to the People of Weimar

On April 16, Third Army commander Patton paid a visit to Buchenwald. Not only was Patton shocked by the stacks of corpses scattered around the camp, their dead eyes staring at him; he was also incredibly angry. He was angry that the Nazis could do this to other human beings and even angrier that the townspeople of Weimar, who undoubtedly knew what had been going on atop the Etterberg hill for eight years, silently condoned it and even profited from it.

To “rub their noses” in the rotting flesh and scenes of atrocities, Patton ordered a thousand citizens of Weimar to march up the hill and forced them to take a guided tour of the camp and view the crematorium with its charred skeletons still in the ovens, the piles of decomposing corpses, the hanging gallows, the whipping bench, the jars from the pathology lab filled with human organs, and the samples of shrunken heads and lamp shades made from tattooed human flesh.

Those Germans with weak stomachs and tender dispositions wept and vomited. Others remained stone-faced, masking their emotions behind impassive glances at the corpses, the gallows, the ovens, the very visible evidence of torture, abuse, and crimes against humanity.

Army photographer Walter Halloran said, “The first group was the men, and of course they were older men because all the young men were in the army. We were so angry we wanted to shoot some of them. They were just rigid and they looked straight forward, not a glance at what was there. Everybody, of course, said they had no idea this was going on.”

One GI noted that, after the tour was concluded, the group marched out through the gate and back down the road to Weimar under American escort. The soldier recalled that he was told, “There was a large patrol of our troops marching them, some on either side of the road. As they were moving back to Weimar, not even out of sight of the camp, a number of Germans in the group found something to laugh about. The commander of the American troops heard them and became livid with anger. He turned them around and marched them back through the camp again. This time they went through much more slowly.”

Buchenwald After the War

In coming days, following a request by Eisenhower to Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall, groups of American newspaper editors and members of Congress also visited the camp to see firsthand the atrocities committed by the Nazis.

Eventually, Buchenwald was emptied of former inmates as members of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration moved in. Many of the ex-prisoners tried to return to their homes and families only to find that their homes and families no longer existed (Robert Max Widerman, for example, learned that practically his entire family had been wiped out). Some emigrated to Palestine (where the new state of Israel would be created three years later), others to the United States, Britain, and France. Others, from Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and other East European nations, did not wish to go to their former homes because the Soviet Union had taken control of those countries.

In fact, during the partition of Germany, Buchenwald fell within the Soviet sector. With no little irony, Josef Stalin’s Soviet Union used Buchenwald for many years as a concentration camp for its political prisoners.

Thirty-two of the perpetrators of the crimes at Buchenwald were hunted down and put on trial in 1947. Hermann Pister was tried and sentenced to death but died of a heart attack while in prison. Ilse Koch was also found guilty and sentenced to life in prison, but her sentence was commuted in 1949 by General Lucius D. Clay, the United States high commissioner for Germany. The West German government, however, rearrested and retried her in 1951. Sentenced again to life in prison, she committed suicide in her cell in 1967.

In October 1990, after the fall of communism and the reunification of Germany, the former camp, with most of its buildings torn down, was opened to visitors from the West and elsewhere as a memorial to the victims of Nazism. It remains a chilling reminder of man’s inhumanity to man.

It is also a warning that such terrible things must never be allowed to happen again—a warning that the world has yet to heed.

Why hasn’t this article been more widely distributed? It needs to be sent to every high school in the country. The government wastes money on so many things; the cost to distribute this is a drop in the bucket! Let everyone know! Let everyone know!!

My great uncle Charlie was there with the 6th Armored Division.