By Blaine Taylor

It was fated to be the last wartime conference of the Big Three Allies of World War II, but it was the first not attended by the late American President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had died at age 63 on April 12, 1945. Taking his place was the new president, Harry S. Truman, also 63, whom neither British Prime Minister Winston Churchill nor Soviet Generalissimo Josef Stalin had ever met before.

How would these two seasoned world leaders size up Truman, and how would the former vice president, U.S. senator, and former Missouri judge do opposite them? People wondered.

Truman and the Potsdam Declaration

In the event, Truman more than held his own, especially after Churchill was replaced as prime minister on July 26, 1945, by the British Labor Party’s Clement Attlee when Churchill’s Conservative Party lost the United Kingdom’s parliamentary election. Of Attlee, Truman later told Churchill, “He’s a modest little bird!” to which Winston replied, “Well, he’s got a lot to be modest about!”

Nazi Germany had been soundly defeated two months before, and thus the main item on the agenda at the Potsdam Conference near Berlin was the defeat of Imperial Japan.

Called the Terminal Conference, it took place July 17 through August 2, 1945, and ended four days before the United States dropped the world’s first atomic bomb on Japan. It was also the only time that Truman and Stalin, soon to be Cold War adversaries, would ever meet.

During this summit meeting, the fate of the former German Reich was sealed for the next 44 years, as it was divided by the victorious Allies into four zones of occupation, the Western part being French, British, and American, and the Eastern part being Soviet. Thus divided, Germany existed until the early 1950s, when the Western zones united to form the Federal Republic of Germany and the East became the Communist German Democratic Republic. These nations coexisted until German reunification in 1989-1990.

On July 25, 1945, the Potsdam Declaration was issued, demanding the unconditional surrender of Japan and threatening complete destruction if this was not done. Unknown to the Japanese, but not to Stalin, 10 days earlier the United States had successfully exploded the first atomic device at Alamogordo, New Mexico. Informed of the details of the success of the test, Truman was, in the words of U.S. Secretary of State Henry L. Stimson, “tremendously pepped up.”

In early August, the twin atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and both cities were obliterated in blinding, instant flashes. Moreover, since March, steady firebombing raids by U.S. Army Air Corps General Curtis LeMay’s deadly Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber armadas had been destroying Japanese cities, and the Soviets had joined the war on the side of the Allies.

To Surrender or to Fight to Utter Destruction

Reluctantly, privately, and in great anguish, Emperor Hirohito, 44, decided that the war must, indeed, be ended, and he therefore called an imperial conference of his top wartime advisers to be convened in his underground air raid shelter on the grounds of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo at 11 am on August 14.

It was hot, sweaty, and stifling in the shelter as the emperor strode into the entranceway of the concrete structure, camouflaged from view under a hill in the palace’s Fukiage Garden, the door covered by hanging tree branches.

The emperor proceeded down a small, darkened hallway, then stepped past a massive door swung open and into the conference hall itself, a small high-ceilinged room with dark, wood- paneled walls. The shelter had been built as an underground attachment of the Gobunko, the emperor’s library, where the emperor lived. It had a conference room 30 feet long by six feet wide. His throne sat at the head of a long table ringed with chairs.

Attending the imperial conference were the members of the Supreme Council for the Direction of the War: director of the Overall Planning Bureau, Lt. Gen. Sumihisa Ikeda; director of the Bureau of Naval Affairs, Vice Admiral Zenshiro Hoshina; Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo; Navy Minister Admiral Mitsumasa Yonai; president of the Privy Council, Baron Kicharo Hiranuma; chief aide-de-camp to the emperor General Shigeru Hasunuma; Prime Minister Baron Kantaro Suzuki; War Minister General Korechika Anami; Army chief of staff General Yoshijiro Umezu; director of the Bureau of Military Affairs at the War Ministry, Lt. Gen. Masao Yoshizumi; and Chief Cabinet Minister Hisatsune Sakomizu.

On August 9 at 11:50 pm, the same group had met there before, on a hot night without air conditioning, making one delegate note, “Even the wooden panels on the thick stone walls were sweating.”

General Umezu, who would later surrender aboard the battleship USS Missouri, made the case for a final, apocalyptic battle of Armageddon, in which every Japanese would fight to the death for the emperor. In this view, Umezu was supported by the Navy chief of staff, Admiral Soemu Toyoda.

The opposite case, arguing for surrender on the Allies’ terms as enumerated in the Potsdam Declaration, was made by Japanese Foreign Minister Togo amid cries of “Defeatist!” from the men around him.

“Voice of the Crane”

As at other meetings previously, there was an impasse in the imperial government, one that only the exalted emperor himself could break if he chose to do so. By 2 am shirt collars had wilted and pools of moisture had formed on the table where the men’s hands were resting.

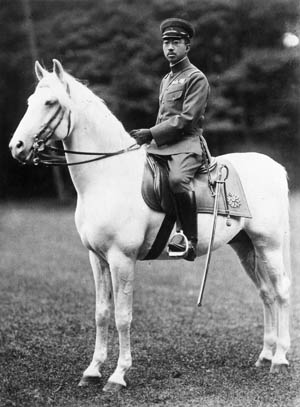

These were the stunned men who now sat facing the emperor as the elderly prime minister put the decision to his majesty. Hirohito sat quietly, in a brown Army uniform, with his cap resting on the table in front of him, his throne on a small, raised platform in front of the folding screen at one end of the hall. To the emperor’s left and right were long tables at which sat his imperial generals, admirals, and ministers—five men to his left and seven to his right. In front of all of them were their caps, folders, and sheaves of papers.

The emperor spoke, as almost never happened at these meetings, in what was euphemistically called the “Voice of the Crane.” Hirohito rose nervously, with notes in hand that he could not read very well, and began in a halting manner as well but calmed down and got better as he went on.

“I was told by those advocating a continuation of the hostilities that by June new battalions would be ready for action in the impregnable positions at Kujukurihama when the enemy began to land. It is now August, and the fortifications have still not been completed. Not only that! The equipment for these battalions is insufficient and, I am told, will not be ready until at least the middle of September.

“As for the promised additions to our air strength, these are not forthcoming, and I understand, will not be.

“I am told that there are those who say that the answer to the survival of our nation lies in the outcome of one last battle, to be fought here, in our homeland. Do we have a plan for this? How is it to be carried out? The experiences of the past show that there has already been a grave difference between our plans and our performances! In the case of the impregnable positions at Kujukurihama, they are not impregnable.

“I do not believe that the difference between what is and what should be can be rectified, and this is the shape of things! How can we repel the invaders?

“I cannot help feeling sad when I consider the people who have served me so loyally, the soldiers and sailors who have been killed or wounded on the battlefields overseas, the families who have lost their homes and so often their lives as well in the air raids here. I need not tell you how unbearable it is to me that others who have given me devoted service should now be threatened with punishment as the instigators of the war.

“In spite of these feelings, so difficult to bear, I cannot endure the thought of letting my people suffer any longer! A continuation of the war would bring death to tens—perhaps even hundreds—of thousands of persons. The whole nation would be reduced to ashes! How could I then carry on the wishes of my imperial ancestors?

“The decision I have reached is akin to the one forced upon my grandfather, the Emperor Meiji. I say it once more! As he endured the unbearable, so shall I! And so must you!

“Nevertheless, the time has come when we must bear the unbearable! When I recall the feelings of my imperial grandsire, the Emperor Meiji, at the time of the Triple Intervention (1895), I swallow my tears and give my sanction to the proposal to accept the Allied proclamation on the basis outlined by the foreign minister.

“I have given serious thought to the situation prevailing at home and abroad, and I have concluded that continuing the war can only mean destruction for the nation and a prolongation of bloodshed and cruelty in the world. I cannot bear to see my innocent people suffer any longer! Ending the war is the only way to restore world peace and relieve the nation from the dreadful distress with which it is burdened.

“Finally, I call upon each and every one of you to exert himself to the utmost so that we may work together in the trying days to come …”

To Remain as Emperor

Hirohito had spoken, the decision for surrender and peace had been made, and that was that. There would now be no more debate, no more discussion. All the men stood and bowed as the emperor rose and left the room—a room that would be sealed from public view until two decades later in 1965, in commemoration of the 20th anniversary of the momentous surrender decision.

Between August 9 and August 14, the Allies had responded to Japan’s offer to surrender under the terms of the Potsdam Declaration in a way that left in doubt the future status of the emperor. The reply had stated, “From the moment of surrender, the authority of the emperor and the said Japanese Government to rule the state shall be subject to the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, Gen. Douglas MacArthur—acting at President Truman’s behest, ultimately—who will take such steps as he deems proper to effectuate the surrender terms …

“The ultimate form of government of Japan shall, in accordance with the Potsdam Proclamation, be established by the freely expressed will of the Japanese people….” This statement related to a democratic system of balloted elections, as in the West.

Unknown to both the emperor and his warlords, however, in Washington the retention of Hirohito as at least the spiritual and symbolic ruler of Japan had already been agreed upon on August 10. Former U.S. ambassador to Tokyo Joseph C. Grew told President Truman at the White House “that even if the question had not been raised by the Japanese, we would have to continue to accept the emperor ourselves under our commander’s supervision.

“In order to get him to surrender the many scattered armies of the Japanese who would own no other authority, and that something like this use of the emperor must be made in order to save us from a score of bloody Iwo Jimas and Okinawas all over China and the New Netherlands.

“He was the only source of authority in Japan under the Japanese theory of the state.”

This was the view also expressed to Truman by Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson and other key advisers. In 1955, Truman himself posed the questions he had faced a decade earlier: “Could we continue the emperor, and yet expect to eliminate the warlike spirit in Japan? Could we even consider a message with so large a ‘but’ to the kind of unconditional surrender we had fought for?”

In 1973, Margaret Truman added, “My father agreed, but in a way that did not compromise his position, that the people of Japan must remain free to choose their own form of government.”

The Coup Plot

It was this vague and veiled assurance that Hirohito had thus ordered his government to accept. By then, it was August 14, the imperial conference had been reconvened, and the emperor rose to speak once more: “I realize that there are those of you who distrust the intentions of the Allies … I appreciate how difficult it will be for the officers and men of the Army and Navy to surrender their arms to the enemy and see their homeland occupied.

“Indeed, it is difficult for me to issue the order making this necessary, and to deliver so many of my trusted servants into the hands of the Allied authorities, by whom you will be accused of being war criminals.

“It is my desire that you—my ministers of state—accede to my wishes and forthwith accept the Allied reply. In order that the people may know my decision, I request you to prepare at once an imperial rescript, so that I may broadcast to the nation.”

Although the emperor was not crying, he had wept before in private, all the other men in the room wept openly, some loudly, in his presence.

What his majesty’s ministers feared even more than Allied occupation was a revolt from within and below from either inside the Japanese armed forces or from the masses of the oppressed people themselves. The dynasty must not be saved by the Allies only to be overthrown by a domestic insurrection. And that was what almost happened, at least from the military side. A small but volatile palace revolt took place, with young, rebel officers bent on a fight to the death rather than a shameful surrender urging War Minister Anami to stage a coup d’état, overthrow the government, and thus prevent the emperor’s planned nationwide radio broadcast to the people.

They wished to “protect” the emperor from what they saw as the treasonous civilian influence of politicians. Thus, they urged the assassination of Premier Zenko Suzuki, Foreign Minister Togo, and Keeper of the Privy Seal Marquis Kido, Hirohito’s top adviser.

Further, the Imperial Palace was to be surrounded by soldiers as martial law was proclaimed. The successful execution of the rest of the coup depended upon the cooperation of War Minister Anami, Army Chief of Staff Umezu, commander of the Eastern District Army General Shizuichi Tanaka, and the commander of the First Imperial Guards Army General Takeshi Mori.

Aside from the United States and democratization, these men and their junior officers feared the communization of Japan even more by the traditional northern enemy, the Russian bear. They also feared what they considered “the depraved and brutalized forces of occupation, pillaging the sacred soil of Japan and raping its womanhood,” as the Japanese Army itself had done in China, Korea, and Manchuria for many years past.

Hirohito’s Surrender Broadcast

Meanwhile, as these and other unknown plots swirled about him, the emperor, dressed in his wartime generalissimo’s uniform that he would soon discard forever for the more Western-looking formal morning coat and tails and civilian business suits, prepared to record his imperial rescript at the facilities of the Japan Broadcasting Corporation in Tokyo.

At the radio station from which the imperial rescript was soon to be heard, an officer stated, “The emperor’s broadcast will be on the air very soon.” A Japanese Kempetai secret police lieutenant drew his sword and shouted, “There won’t be any broadcast! I’m going to kill them all!” and rushed for the studio, but he was soon subdued and handed over to his very own Kempetai police for rebelling against the emperor’s orders.

During his first-ever broadcast, the emperor noted, “The enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is, indeed, incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives. Should we continue to fight, not only would it result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization …”

Afterward, the studio engineers indicated that some of the words were unclear on the recording, so the emperor made a second recording and was willing to make a third if necessary. There were tears in his eyes now, as well as in those of the other men present.

526 Suicides

Meanwhile, at Imperial Guards headquarters, the tension had expressed itself in the murder of both General Mori and his brother-in-law, Lt. Col. Michinori Shirashi. Two young officers looked into the murdered general’s office as a third wiped Mori’s blood from his sword. The hacked, bleeding bodies lay on the floor beneath him with blood still spurting from their wounds. The lieutenant colonel had his head sliced off, and the office walls were liberally splashed with red; the floor was both dark and slippery.

While General Anami planned his own suicide to escape either surrender or participation in the plot, Marquis Kido was hidden from the plotters. The rebels’ reasoning was that in 1936, when the growing drift toward war had been opposed, the pro-war faction simply murdered the opposition leaders in a wave of bloody assassinations, and now they planned to abort the projected surrender in the same way. In all, 376 Army men from private to general, 113 Navy men from seaman to admiral, and 37 nurses and civilians also died by their own hands that week, a grand total of 526.

Rebellion Against Hirohito

At the Imperial Palace, the emperor was awake and listening as his court chamberlains debated how best to safeguard his majesty’s life if it came to that. It was decided to bar all the doors and fasten all the Gobunko’s shutters, but the latter had become so rusted over many years of nonuse that the chamberlains were unable to shut them.

Finally, they ordered some tough young Imperial Guards to bar all the windows, and one chamberlain mused how ironic it was that this was being done against Japanese—and elite Imperial Guards at that—and not enemy soldiers.

Later, Premier Suzuki’s residence was machine-gunned, and Kido’s villa was also attacked, while Chamberlain Yoshihiro Tokugawa faced down his dispatched killers. According to one account, Tokugawa was assaulted. “A fist struck him full in the face, and he fell to the floor, his eyeglasses crushed beneath him….”

And now, the imperial library itself was surrounded by rebellious troops: “I still can’t believe it!” asserted Fujita, who opened one of the iron shutters to peep out, seeing knots of Imperial Guards occupying key posts between the Fukiage Gate and the Gobunko. ”Machine guns were being placed with their muzzles pointing squarely at the house of the emperor!” noted another account.

Meanwhile, Anami committed hara-kiri, and, slowly, the plot began to lose steam. One of the chief plotters, Major Kenji Hatanaka, shot himself in front of the Imperial Palace, while another, Lt. Col. Jiro Shizaki, stabbed himself with a sword in his belly as he also shot himself in the head.

Prime Minister Hideki Tojo’s son-in-law, Major Hidamasa Koga, sliced open his own stomach in the sign of a cross, it was recalled later. The captain of the Air Force Academy who had murdered Shirashi killed himself on the 16th, the day after his majesty’s historic radio broadcast, while the entire Oyodomari family slaughtered itself en masse on September 2, the day of the signing of the surrender documents aboard the USS Missouri.

In 1960, a full 15 years after the events of August 1945, an Army sergeant sought out Chamberlain Tokugawa to offer an apology for having hit him, bringing as a peace offering an important family possession, a tea kettle made from a bronze mirror.

How many more lives were violently lost in the brief palace revolt against Hirohito’s historic decision for peace? The actual number is not certain. More visible, however, was the public reaction to the imperial rescript broadcast, with squares full of weeping citizens and men falling to the ground and banging their heads on the pavement. Some others intermittently shot and stabbed themselves, with crowds bowing low to each such corpse as they uttered quiet prayers for the departing spirits.

MacArthur Occupies Japan: “This is the Payoff!”

The broadcast was indeed heard and acted upon, and the surrender became history. On August 24, 1945, General Tanaka shot himself through the heart after having first suppressed an attempt by military students to occupy the Kawaguchi broadcasting studio.

Now, an improbable event was about to happen. The first foreign occupation force ever was going to set foot on the soil of the Japanese Empire, and it was to be led by General Douglas MacArthur, who had three years earlier been driven from his Philippine Islands command by the forces of this now vanquished nation.

One who was aboard the general’s aircraft that day was CBS Radio News correspondent William J. “Bill” Dunn, who recalled in 1988 what it was like: “The major who occupied the adjoining bucket seat nudged me in the ribs … ‘Look, Bill, is that it?’ That, indeed, was it: a perfect snow-capped cone rising dimly above the mists that covered most of the distant hills to the north … Fujiyama, Nippon’s exquisite sacred mountain …”

Thus, a modern “invasion” of the fabled land of the Rising Sun was about to begin. A little after dawn on August 28, 1945, a total of 45 C-47 transport aircraft approached Mount Fuji with an American advance party.

No sooner was Atsugi Air Base outside Tokyo secured than MacArthur’s own C-54 airplane, named Bataan, landed at 2:19 pm, with the general himself appearing first at the opened door. Wearing his famed Philippine Army cloth field marshal’s cap, his equally famous corncob pipe between his teeth, a jubilant MacArthur chortled, “This is the payoff!”

MacArthur’s motorcade into Tokyo was guarded by no less than 30,000 Japanese troops, their backs facing their conquerors, their weapons held at port-arms. There are two versions of why this was done: first, to protect the general from any would-be Japanese assassins and, second, as a sign of contempt.

That night, an ebullient MacArthur told his personal staff after dinner, “Boys, this is the greatest adventure in military history! Here we sit in the enemy’s country with only a handful of troops, looking down the throats of 19 fully armed divisions and 70 million fanatics. One false move, and the Alamo would look like a Sunday school picnic!”

Surrender on the Missouri

U.S. Navy Secretary James Forrestal selected the Missouri as the site of the surrender. The battleship was anchored 18 miles out in Tokyo Bay, and the date chosen was September 2, 1945, six years and a day after the invasion of German tanks that raced across Poland and began the largest war in recorded human history.

MacArthur came aboard ship at 8:40 am, went to the bathroom in the captain’s cabin, and threw up, according to his longtime personal pilot, “Dusty” Rhoads. “I asked him if he wanted me to get him a doctor, but he replied that he would be all right in a moment. Soon afterward, he emerged, went on deck, and staged the ceremony without a quiver in his voice. I believe that his momentary problem was merely an emotional reaction to his realization that this occasion could be his final significant action in a long and illustrious military career.”

It was not, however, as ahead lay MacArthur’s term as Allied ruler of postwar Japan, the tumultuous Korean War, and his firing by President Truman.

For his part, Japan’s Emperor Hirohito did not appear in person, but instead sent a delegation consisting of Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu for the government, and the

Chief of the Army’s Imperial General Staff Yoshijiro Umezu, as well as Admiral Sadatoshi Tomioka to represent the Navy that had launched the war with the Pearl Harbor attack back in 1941.

The weather was clear and bright, with Mount Fuji visible 60 miles away. Tokyo Bay overflowed with Allied warships, and the bright sunshine sparkled on the white uniforms of the U.S. sailors. On one side lay the battleship USS Iowa and on the other, the South Dakota.

On a side of one of the Missouri’s massive gun turrets hung the American flag with 31 stars that Commodore Matthew C. Perry had brought with him to this same Tokyo Bay when he “opened” Japan to the West 92 years earlier. Also present was the American flag that had flown over the U.S. Capitol on Sunday, December 7, 1941.

Assembled on the deck for the Japanese were all the top Allied officers of the Pacific War that Japan had just lost. The 11-member Japanese delegation came aboard. Shigemitsu had lost a leg in a prewar assassination attempt and had difficulty getting on deck. Not knowing this, however, none of the Allies would help him up. It was 8:55 am, and the onlookers watched his plight “with savage satisfaction,” in the words of one scribe. Finally, a hand was offered in help, but he refused it.

MacArthur strode on deck precisely at 9 am and read a brief statement he’d been allowed by Washington to draft on his own, and then the signatures were affixed to the document by both sides. A drunken Allied delegate made faces at the Japanese. MacArthur intoned, “Let us pray that peace now be restored to the world, and that God will preserve it always. These proceedings are closed.”

Thousands of Allied planes swept overhead, the Allied world rejoiced, and World War II was over at last.

Emperor Hirohito died of cancer at age 87 on January 7, 1989, and was succeeded by his son, Crown Prince Akihito, on the Chrysanthemum Throne. Alone among the former Axis powers, Imperial Japan today still flies the same flags it did during World War II—the rising sun and its rays and the single sun ball. Hirohito had won a victory after all.

We should realize that the dialog by Hirohito as reported may not be exactly as spoken. While the general tenor of the conversation is probably correct, the comments and actions by the participants during meetings may have been “edited”. To compound the difficulty of getting a completely accurate record, Hirohito destroyed his diaries prior to his death.