By Dr. Carl H. Marcoux

A small group of Americans, operating behind the Japanese lines in Burma from 1942 until mid-1945, played a major role in neutralizing a large enemy force. Ultimately, the Japanese had to give up control of Burma, ending Japan’s threat to invade India. Office of Strategic Services (OSS) Detachment 101 consisted of a handful of Americans who trained and led a powerful guerrilla contingent that harassed the Japanese Army continuously as the Japanese sought to use Burma as a major base for their military domination of Southeast Asia.

Following the Pearl Harbor attack on December 7, 1941, the Japanese invaded Malaya, Borneo, and Burma as well as the Dutch East Indies and the Philippines. They also invaded a number of smaller islands in the South and Central Pacific, securing most of these targets with little opposition. After five months of war, the Japanese were poised to threaten both Australia and India.

The Japanese Occupation of Burma

The Japanese conquered Burma with little difficulty in the spring of 1942. The principal cities of Rangoon and Mandalay quickly fell to the invaders. Those British and Indian troops that could, escaped to India. A Chinese army, under the command of American General Joseph Stilwell, was also forced to retreat. Stilwell himself barely escaped capture by the rapidly advancing Japanese forces.

Many of the lowland Burmese populace aided the invaders. They helped the Japanese by supporting their fifth-column activities during ambushes, night attacks, and demolition work. These Burmese hoped that their country, with the departure of the British, would achieve independence for the first time in eight centuries. The Japanese propagandists had preached the doctrine of “Asia for the Asians.” Unfortunately for the Burmese, they experienced an even a greater degree of social, economic, and political oppression under the country’s new occupiers.

Burma represented a key factor in the progress of the war in Southeast Asia. The Burma Road, through the country’s northern highlands, represented a major link in the shipment of war material to Chinese forces from Allied bases in India. After the Japanese captured Burma, the Allies had to supply the Chinese by air, over the forbidding Himalayas. The hazardous air route was nicknamed “the Hump.” It was a much less efficient—and more costly—transfer of critical goods. Burma also represented a key staging area for any Japanese plan for the invasion of India. It became critical for the Americans and the British to retake Burma to reduce these threats to the successful pursuit of the war in Southeast Asia.

Creating a Guerrilla Army From Scratch

The U.S. government, meanwhile, was working on plans for combating the Japanese. These strategists reached the conclusion that espionage and subversion would have to be employed in any successful attempt to liberate those countries now under Japanese control. American President Franklin D. Roosevelt admired the well-established programs of this nature employed by the British, whose Special Operations Executive (SOE) Roosevelt sought to emulate.

Roosevelt selected General William J. “Wild Bill” Donovan, who had been a classmate of the president at Columbia Law School, to set up a program similar to that operated by the British. Originally called the Office of the Coordinator of Information, the designation would soon be changed to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner of the modern Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). At the time a Wall Street lawyer and a former assistant U.S. attorney general, “Wild Bill” Donovan had been the commanding officer of the U.S. Army’s famed Fighting 69th Regiment of the Rainbow Division during World War I. He and General Douglas MacArthur were the only two soldiers who held three of the nation’s top medals: the Medal of Honor, the Distinguished Service Cross, and the Distinguished Service Medal.

Burma was certainly an area where a program of subversion and sabotage could be used to great advantage by the Allies. The country’s north was covered largely with a dense jungle —a perfect cover for guerrilla warfare. Soon after his appointment, Donovan got in touch with General Stilwell to map out such a program. The task of establishing units capable of such work had to be started from scratch, since the Army had no such agenda in existence.

Fortunately, Stilwell had a candidate to lead this unit for the planned incursions into Burma. Captain Carl Eifler commanded a company of the 35th Infantry Regiment in Hawaii. Eifler cut an imposing figure. Standing over six feet, two inches tall, weighing more than 250 pounds, and skilled in jujitsu, Eifler, Stilwell believed, possessed the characteristics needed to lead such a demanding program. Eifler, for his part, immediately began recruiting a group of officers and noncommissioned officers that he felt could aid in developing a team for the mission ahead.

The new mission’s chief traveled to Washington, D.C., met with General Donovan, and listened to the latter’s rather vague ideas on organization and training. Following the meeting, Eifler established a series of training facilities in Maryland. Chief among these was Area B, some 70 miles from Washington. The site later became Camp David, a vacation retreat for American presidents.

OSS Detachment 101

The unit, officially designated as OSS Detachment 101, consisting initially of 21 members, began an intensive training program in early April 1942. William A. Peers, who later succeeded Eifler as commander of Detachment 101, said in his memoirs that the designation for the group was chosen to give the impression that the unit was well established and had been activated for a considerable length of time.

The curriculum included learning the use of high explosives, cryptography, methods for search and rescue, and many other specialties associated with subversion and sabotage behind enemy lines. Members of the group also received intensive training in techniques of unarmed combat to prepare them for face-to-face contact with the enemy.

The combat training involved brutal, destructive, and aggressive methods of dealing with the enemy. Capture could mean torture and even death. OSS participants carried lethal capsules that would allow the agents to commit suicide, if they chose, rather than endure torture in the event of their capture by the enemy.

Parachute jumping represented a critical element of OSS training. Operatives would be expected to land behind enemy lines if they were to successfully execute sabotage missions. The training also involved techniques for landing on enemy beaches with small craft launched from submarines. The training was made as realistic as possible.

Training For the Pacific Theater

In late 1943, a program specifically designed for the Pacific Theater was established. An OSS training center was established at Toyon Bay, the site of a prewar boys’ school on Catalina Island, off of the coast of Southern California. The site was chosen because of its isolation and relative inaccessibility.

The training period turned out to be quite brief for those scheduled for the China-Burma-India Theater. The new team left for Asia in late May 1942. Travel to the unit’s new assignment was by slow freighter. The ship also carried what limited supplies Detachment 101 could acquire on short notice in preparation for deployment.

The detachment arrived at Karachi, now part of Pakistan, on July 4, 1942. The men then traveled across India to Nazira, Assam, in the country’s northeast, close to the Burmese border. The U.S. Air Transport Command (ATC), responsible for flying supplies to China, maintained several airfields in the vicinity of the town. The Americans quickly established contact with local British authorities, who had extensive knowledge of Burma and Japanese activities in the country.

Detachment 101 set up a program for its first recruits and began instruction on demolition techniques and methods for the destruction of a wide variety of targets critical to Japanese military operations. The American instructors learned almost as much from their pupils, initially mostly British and Anglo-Burmese, as they taught them. This first group of potential saboteurs knew a great deal more than its American teachers about the Burmese people and territory.

Winning Over the Burmese People

The Americans also realized that the long-range success of their mission would require the assistance of a large number of indigenous Burmese. The accomplishments of the Japanese during their invasion of the country were due in no small part to the assistance of lowland Burmese people who had believed that their fellow Asians would be their liberators. Ultimately, such proved not to be the case, and the Burmese soon became disillusioned because of the treatment they received at Japanese hands.

Burma has a mixture of a number of different ethnic groups, often speaking different languages and dialects. Separate from the Burmese peoples living in the arable lowlands are the hill tribes in the country’s mountainous north. These peoples, the Karens, Shans, Papaung, Chins, and especially the Kachins, were much more warlike and aggressive than their southern neighbors. During the 1940s, they lived in isolated villages located in dense forest areas. These tribes had developed a working relationship with the British and had made up the majority of the native troops trained and officered by the Europeans before the war began. The hill people made superb jungle fighters and, as such, were potential candidates for a guerrilla force capable of seriously impacting the ability of the Japanese to control the country’s mountainous areas. The Americans sought to win these fighters quickly to the Allied side.

The Three Objectives of Detachment 101

The strategy of Detachment 101 designed for the Burma campaign consisted of the following: (1) the destruction of targets of opportunity such as bridges, railways, and mines used by the Japanese in controlling the country and in shipping supplies and equipment throughout the countryside, (2) the ambush of enemy personnel where practical, as well as spying on their movements, and (3) the recovery of airmen downed in Japanese territory.

The detachment planned to parachute small teams of men into remote jungle areas as close as possible to their intended targets. Each unit would contain some Kachin natives to act as guides as well as saboteurs. The Kachins knew the country and could act as translators when the teams encountered their fellow tribesmen in the hill villages.

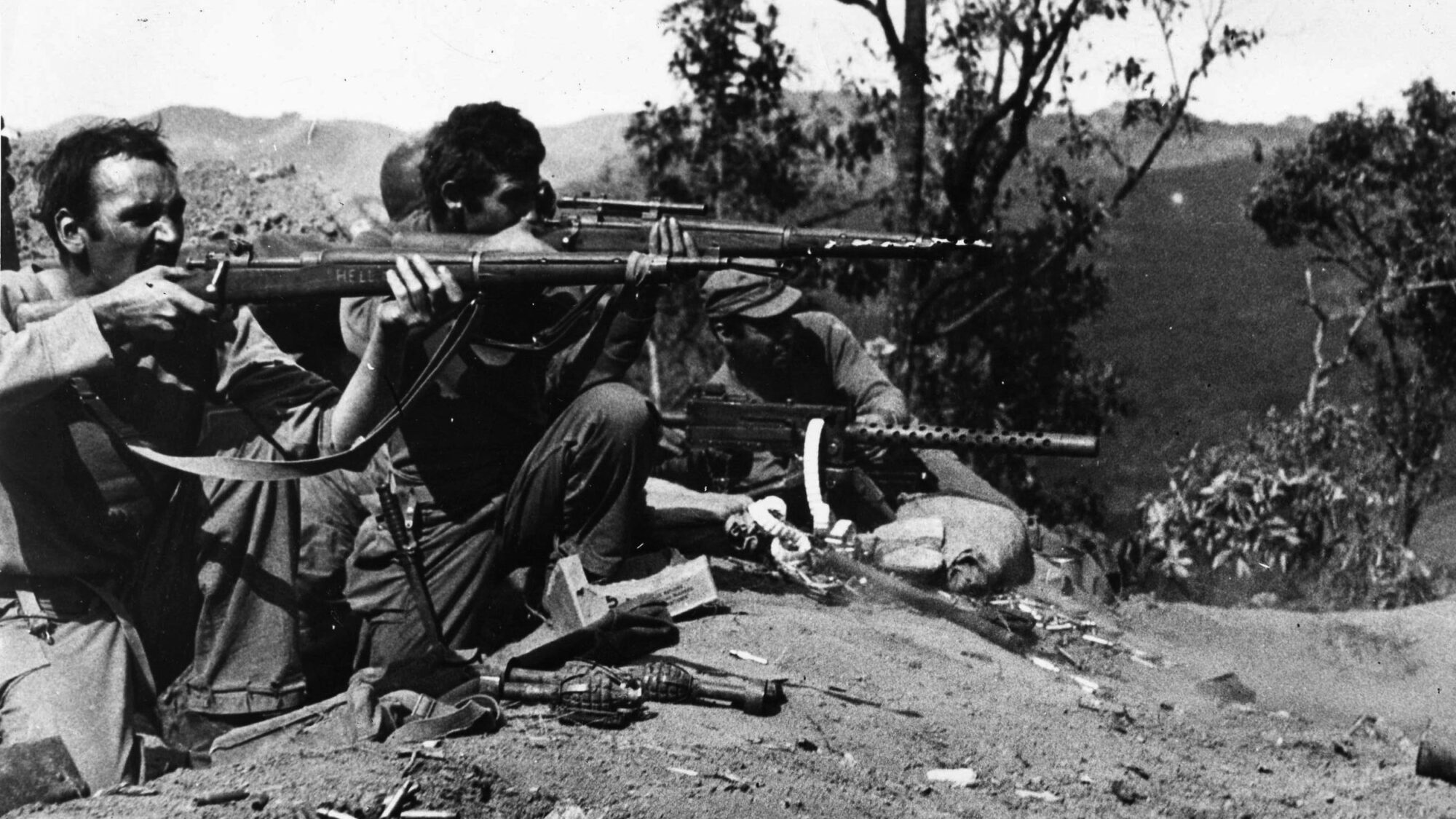

Guerrilla tactics involved a sudden strike on an unsuspecting target, its destruction, and then a quick retreat to safety. No prolonged engagements were contemplated. The advantage lay with the attackers as long as they struck quickly and then vanished. The detachment and its Kachin recruits proved to be adept at this type of warfare. The jungle, despite all of its problems and hazards, furnished ideal camouflage for its hit-and-run tactics. The Kachins took advantage of the undergrowth to plant pungis, two-foot strips of bamboo shaped like spears and hardened over fire until they were as sharp as steel. These were placed alongside the jungle trails and caused serious injury to unsuspecting Japanese troops.

Fighting Behind Enemy Lines

The ATC agreed to furnish C-87 aircraft to carry the teams and their equipment into enemy territory. The Air Corps had converted these cargo planes from B-24 Liberator heavy bombers. The aircraft also had to be rigged to permit the exit of parachutists. These planes were also used for supply missions and to pick up team members after they had completed a mission. The ATC furnished the necessary aircraft whenever possible. Often, it was downed ATC personnel that the teams would be seeking to return to the safety of their bases. The teams sometimes had to extract themselves from enemy territory on foot if rescue by air proved to be impractical.

To take Burma back from the Japanese, General Stilwell was compelled to keep open both a major road and a rail line between Calcutta, India, and his Chinese troops in the field. A loss of these vital routes would allow resupply of these troops by airlift only and materially reduce the effectiveness of the Chinese forces as a result. Detachment 101 operated behind Japanese lines, ambushing isolated Japanese units when possible, seriously interdicting enemy supply lines, and reporting Japanese troop movements by radio.

Stilwell’s Assault on Myitkyina

In April 1944, Stilwell launched his coordinated attack on the main Japanese base in northern Burma—Myitkyina. Japanese aircraft based at Myitkyina harassed Allied supply lines connecting the Ledo Road with the Burma Road, the major supply line on the ground to the Chinese troops in eastern Burma and beyond. Stilwell’s three-pronged strike force consisted of 3,000 recently recruited American volunteers who came to be known as Merrill’s Marauders, a mixed but experienced British force called the Chindits (a combination of British, Gurkha, Nigerian, Chinese, and Burmese troops), and two Chinese divisions, the 22nd and the 38th. The Chinese troops had been trained in India by a team of U.S. Army instructors under the supervision of Stilwell himself.

Stilwell directed the Chinese to begin a direct frontal assault on the Japanese stronghold, the Americans to attack from the east around the Japanese right flank, and the Chindits, moving west from India, to infiltrate the area behind Japanese lines from that direction. During the advance of Stilwell’s main forces, Detachment 101 continued to disrupt Japanese communications and supply operations behind enemy lines and acted as guides for the advancing Allied troops.

By May 17, the Allies had captured the city’s critical airstrip, and the battle for control of Myitkyina appeared to be over. Then disaster struck. Stilwell decided to give the honor of completing the capture of the city to some of his Chinese units. However, the two Chinese battalions ordered to take the city were relatively inexperienced. They attacked one another by mistake and had to be withdrawn after the friendly fire had exacted heavy casualties.

The Japanese rallied quickly and even managed to send some reinforcements and supplies to their beleaguered defenders. It was not until August that Allied troops finally managed to force the Japanese out of Myitkyina, requiring the enemy to retreat to their bases in Burma’s southern reaches. The loss of Myitkyina ended the threat of Japanese aircraft against the Ledo and Burma Roads.

The High Cost of Battle

Detachment 101 continued to harry the enemy during its retreat southward. Only a relative few enemy soldiers managed to reach the Japanese base at Bhamo. However, Stilwell’s strike force—the Marauders, the Chindits, and the Chinese—also suffered substantial battle casualties. The attacking troops had been subjected to a variety of debilitating tropical diseases in the lengthy process of capturing Myitkyina. After being relieved by occupation troops, those combatants that had taken the town required extensive rest and rehabilitation. The Marauders’ losses proved to be so severe that they virtually ceased to function as a unit after the battle. The Chindits suffered the same fate within a few months as they continued to suffer severe losses in their accelerated movement southward in pursuit of the Japanese.

The leaders of both the Marauders and the Chindits also met with personal disaster. General Frank Merrill, for whom the Marauders were named, suffered three disabling heart attacks and had to be replaced during the Myitkyina campaign. Brigadier Orde Wingate, the charismatic leader of the Chindits, died in an airplane crash on March 24, 1944.

A String of Japanese Losses

The loss of Myitkyina was the first of a continuous series of defeats for the desperate, slowly retreating Japanese infantry. They now faced a constantly expanding, well-supplied Allied army that also controlled the air. The Japanese, on the other hand, no longer received reinforcements to replace their dwindling manpower and found that their now greatly diminished supply lines faced constant harassment by Detachment 101’s Kachin Rangers. Detachment 101 also received orders to expand the training program for the Burmese fighters, which now included many southerners, Shans, and other lowland Burmese, who had initially supported the Japanese. By this time, the guerrilla forces under Detachment 101’s leadership were numbered in the thousands.

Toward the end of the fighting in Burma, Detachment 101 also launched an intensive propaganda campaign, dropping leaflets written in Japanese and purportedly issued by the Japanese high command, ordering their troops to surrender. The leaflets further lowered the morale of the hard-pressed, retreating Japanese. Although the enemy troops continued to fight fiercely, they lost town after town. Finally, both Mandalay and Rangoon, the country’s principal cities, were liberated.

Detachment 101’s Remarkable Success

By mid-July 1945, orders from Washington deactivated the OSS Burma operation. The remarkable success of Detachment 101’s guerrilla activities was borne out by an impressive set of statistics. At its peak, the detachment numbered only 689 Americans, 131 officers and 558 enlisted men. During the course of its operations, the unit was able to train more than 10,000 native troops, mostly Kachins, in the techniques of guerrilla warfare.

The Northern Combat Area Command’s (NCAC) statistics indicated that Detachment 101 had killed or wounded an estimated 10,000 Japanese, captured 75, taken down 51 bridges, derailed nine trains, and destroyed 277 enemy vehicles. Of paramount importance to their operations, too, was the rescue of some 232 downed U.S. airmen, whose planes had been lost in the airlifts over the Hump to China.

The NCAC stated that the great majority of the intelligence provided to the command came from Detachment 101. Yet, the cost in American lives proved to be surprisingly small. The enemy succeeded in killing only three Americans from Detachment 101. Another 19 were lost in air crashes. Ultimately, on January 17, 1946, the War Department awarded the members of the detachment a Distinguished Unit Citation for their accomplishments in the China-Burma-India Theater.

Major General William J. “Wild Bill” Donovan, creator of the OSS and chief architect of successful covert operations in Burma during World War II, died February 8, 1959.

Dr. Carl H. Marcoux is a World War II veteran of the U.S. Merchant Marine and a Korean War veteran of the U.S. Air Force. He resides in Newport Beach, California.

My Father, William H. McClare was a liaison pilot assigned to OSS Detachment 101. For his actions he was awarded two Distinguished Flying Crosses and the Air Medal. After the war he went back to college, on to law school and then had a career with the newly formed Central Intelligence Agency. He was assigned With other CIA agents to Chiang Ke Shek. He later was involved in the Bay of Pigs operation.

He passed away in 1970.

Thanks for writing and sharing “Yankee Guerrillas in Burma: The story of OSS Detachment 101 in Burma“

Thanks for an interesting article. I’ve always been interested in the history of the CBI and OSS operations in Burma during WWII.

My Dad was a Marine in Detachment 101 of the OSS John Kniest(Jack) ✝️❤️ Thanks Dad and Norm Abbott ,Bill Eubanks and ALL Those in 101 ???✝️

Does anyone have any information on doctors that supported OSS 101 from Lido

forward? I have anecdotal information that my father humped the mountains getting

wounded flyers out. He was Dr. Walter Rowson, Captain, US Army.

Any information at all will be greatly appreciated.

thanks

Dave rowson

My neighbor, Kenneth Kegg from Santa Cruz, California was recruited for this Burma Operation, we talked at length back in the early 90’s. I presume he has passed on by now. But his CO knew many languages and threatened to kill my neighbor if he ever disobeyed an order. My neighbor had to kill an informant after his CO overheard conversations between some Chinese in their camp.