By John W. Osborn, Jr.

“The problem,” a member said, “is to make yourself so much master over the appalling difficulties of nature—heat, thirst, cold, rain, fatigue—that, overcoming these you yet have physical energy and mental resilience to deal with the greater object, the winning of the war.”

The men of the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG) in the Middle East in World War II did this, and more. The LRDG had been variously described as “arguably the most dashing and successful irregular formation on either side in the entire war,” and “probably one of the most cost-effective special forces in the history of warfare.” It carried out some 200 missions across a desert the size of India, then through the Mediterranean, the Balkans, and the Adriatic; in five years of existence, there were only five months when an LRDG patrol was not on an operation.

“Piracy on the High Desert”

The Long Range Desert Group was created, literally, by accident. A collision in a British convoy in the Mediterranean Sea forced a troopship to dock at Alexandria, Egypt, for repairs. Among those deposited there was Major Ralph Bagnold of the British Army’s Royal Engineers en route to a posting in East Africa.

From 1925 to 1935, Bagnold had explored the Great Libyan Desert, 1,100 miles east to west, 1,000 miles north to south, as part of an international group that included the future central character of the novel and film The English Patient, Hungarian Count Laszlo Almasy. “Never in our peacetime travels had we imagined that war could ever reach the enormous empty solitudes of the inner desert, wailed off by sheer distance, lack of water and impassable seas of sand dunes,” Bagnold remembered. “Little did we dream that any of the special equipment and techniques we had evolved for very long distance travel, and for navigation, would ever be put to serious use.”

A notice about Bagnold in an Egyptian newspaper led to him being sent for by the British commander in chief of the Middle East, Sir Archibald Wavell. Bagnold recalled how Wavell “sat me in an armchair, and I told him what I thought was wrong. ‘We ought to have some mobile ground scouting force, even a very small scouting force, to be able to penetrate the desert to the west of Egypt, to see what was going on. Because we had no information on what the Italians might be doing.’ (The Germans had not yet intervened in North Africa.) He said, ‘What if you find that the Italians are not doing anything in the interior at all?’ I replied without thinking. ‘How about some piracy on the high desert?’ His rather stern face broke into a broad grin, ‘Can you be ready in six weeks?’”

Assembling the LRDG

Bagnold was ready in just five weeks. For vehicles he chose Chevrolet trucks for their proven durability in the desert, though they got only six miles to the gallon out there. For equipment, he used a sun compass he had designed and army radios with a skip range of 1,200 miles. For his men he rejected death or glory daredevils and instead contacted old desert hands and recruited 150 New Zealanders (200 eventually served) for their toughness, even temperament, and being used to repairing trucks on their farms.

In its first operation, in August-September 1940, the Long Range Desert Group proved its worth and routed the skeptics as two units, one led by Bagnold, crossed 4,000 miles undetected, scouted and attacked Italian outposts, survived the paralyzing heat of the day and freezing cold of the night, then successfully rendezvoused. From then on until the end of the campaign at least one LRDG unit was always out on patrol.

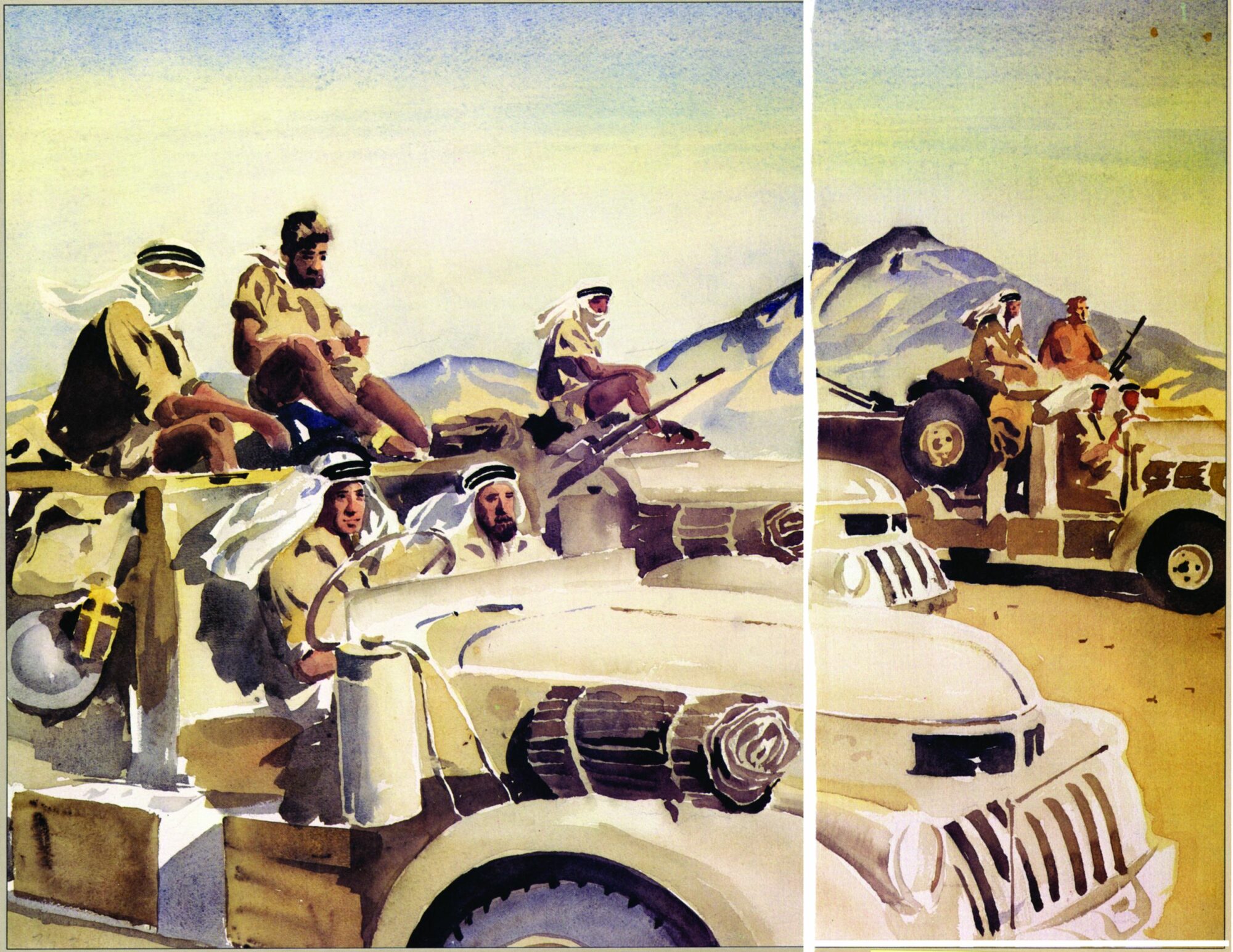

An average LRDG patrol was composed of 40 men in 10 vehicles (most of them carrying fuel, water, ammunition, spare tires, and food), lasted three weeks, and covered 2,000 miles. “The men of the LRDG patrols were quite a sight on their return to Cairo from a month’s trip to Libya,” wrote Saul Kelly in The Last Oasis. “Unwashed (for the water ration did not allow it), bearded, burnt brown by the sun and clad in ragged shirts, shorts, and sandals, they had the air about them of a bunch of wild-eyed Biblical hermits emerging from their sojourn in the Wilderness.”

The Perils of the Desert

Survival depended daily on concealment. Trucks were camouflaged with scrub or nets. Then it was found that painting the trucks rose pink and olive green made them almost invisible from the air. Patrols could simply stop at the sound of approaching aircraft and let them pass over.

Survival in crisis depended on ingenuity and sheer will. A cracked crankcase was repaired with a mixture of sand and chewing gum. When patrols did come under air attack, they would drive into sandstorms and even into the dust clouds kicked up by the exploding bombs being dropped on them. Trooper R.J. Morse, wounded and separated from his patrol, walked 210 miles until he was picked up.

But the heat was as dangerous an adversary as the Germans and Italians; the men of the LRDG had to endure temperatures of 120 degrees in the shade on just six pints of water a day. “You don’t merely feel hot, you don’t merely feel tired, you feel as if every bit of energy had left you, as if your brain was thrusting its way to the top of your head and you want to lie in a stupor until the accursed sun has gone down,” an officer said.

Like explorers, the men of the LRDG had to find a way or make one. One of Bagnold’s old desert hands, Captain William Kennedy Shaw, said, “You were in another world. A treeless, plantless, waterless, nameless world, almost featureless.” Progress could be as little as four miles a day, tires deflated to keep the trucks from bogging down in sand. One of the few maps the LRDG had was captured from the Italians. “The mountains were all high, as became the dignity of Fascist Italy. Making our way anxiously toward an obviously impassable range of hills, we would find we had driven over it without feeling the bump,” an LRDG officer said.

The Three Rs

The Long Range Desert Group’s operating three R’s were reconnaissance, road-watching, and raiding. Underlying them was a fourth R. As military historian Brigadier Julian Thompson wrote, “They were utterly reliable. If they said they would arrive at an exact spot in the desert 1,000 miles away at a certain time, they almost invariably did.”

General Bernard L. Montgomery, the hero of El Alamein, said that, but for the LRDG’s probing of the Mareth Line in Tunisia, his attack “would have been a leap in the dark.” The head of military intelligence in the Middle East considered the LRDG’s surveillance of the Tripoli-Benghazi road—confirming intelligence reports of the strength of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps—to be its single most important contribution to the campaign. Of those nerve-wracking vigils, concealed and not daring to move, an LRDG man wrote, “You look at your watch at 11:00 and look again four hours later and it’s 11:15.”

The LRDG planted mines, ambushed convoys, and roared out of the night onto enemy bases and runways, machine guns blazing and blowing up fuel depots and aircraft, sometimes destroying or damaging dozens of planes in a single raid. “To the Italians, the raiders seemed to appear from nowhere, as if from a fourth dimension, and to disappear as rapidly,” wrote Bagnold. One unit had simply driven up the open road to their objective past enemy vehicles. Since the Germans and Italians utilized captured British trucks no one paid them any attention!

The Germans conceded, “The LRDG plays an extremely important part in the enemy sabotage operation,” and paid it the compliment of forming its own version led by Bagnold’s old desert colleague Count Lazslo Almasy. Despite the curious use of his real name, the depiction of Almasy in The English Patient is entirely fictitious. He was an active Nazi who also happened to be homosexual. He died, not horrifically burned in an abandoned Italian villa in 1945, but of dysentery in Innsbruck, Austria, in 1951. In his memoirs, Bagnold only mentions Almasy as “a Hungarian desert enthusiast who had lately served on Rommel’s staff.”

The LRDG also guided other forces to their objectives, rendezvoused, then brought them out. It took Free French troops over 500 miles into the central Libyan desert to capture the Koufrah Oasis in January 1941, and it worked with the Special Air Service (SAS) on many operations, including leading them 1,200 miles to raid Tobruk in September 1942. One secret group the LRDG led to its objective was composed of German Jewish refugees from Palestine in Afrika Korps uniforms along with a supposedly defecting German prisoner. The mission ended in disaster. Only one survivor reached the rendezvous to report the German POW had betrayed the mission.

The LRDG Leaves North Africa

Driving out of the desert for the last time at the end of the Middle East campaign, an LRDG man said, “It’s like saying goodbye to an old schoolmaster, who was very severe and frightening, but whom one knew one was very fond of.” But the Long Range Desert Group’s heaviest fighting and losses lay ahead.

Operating mainly as a commando unit, the LRDG went on to see action in Italy, Yugoslavia, Albania, and the Dalmatian islands. In a throwback to its surveillance role, it performed valuable coast watching as it searched for German convoys along the Aegean and Adriatic coasts; one patrol spent 17 days on the Greek island of Naxos evading a 650-man German garrison to report on German shipping in the harbor for the Royal Air Force to attack.

The LRDG killed 50 Germans at a roadblock ambush in Greece, 80 at another in Albania. But while the force had lost 16 killed and 24 missing and captured in the whole Middle East campaign, it had 41 killed in a raid on the Greek island of Levitas in October 1943, and a month later Bagnold’s successor as LRDG commander, Jake Easonsmith, was killed and 50 were captured on the nearby island of Leros.

With the end of the war against Nazi Germany, most of the LRDG, though eligible for demobilization, volunteered for the Pacific. However, the offer was refused and the Long Range Desert Group was disbanded in August 1945. Ralph Bagnold continued his desert research, once having an uncomfortable meeting with Count Almasy at an experts’ conference in Cairo. Bagnold lived to see the work that had been used for war put to another purpose. His study of desert sand was used by NASA in designing its Mars landing probe.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments