By Jim Foral

Along with the news of the American battleship Maine’s suspicious sinking in Havana harbor in February 1898 came the unmistakable scent of war. A northwest breeze wafted it into the particularly keen and receptive nostrils of every red-blooded male of military age in the United States. For two generations, dormant patriots had been denied the experience of combat, and there was a great hunger for the sting and glory of battle. So many wanted to enlist that not all could be accommodated, and grown men shed real tears of disappointment at recruiting booths across the country.

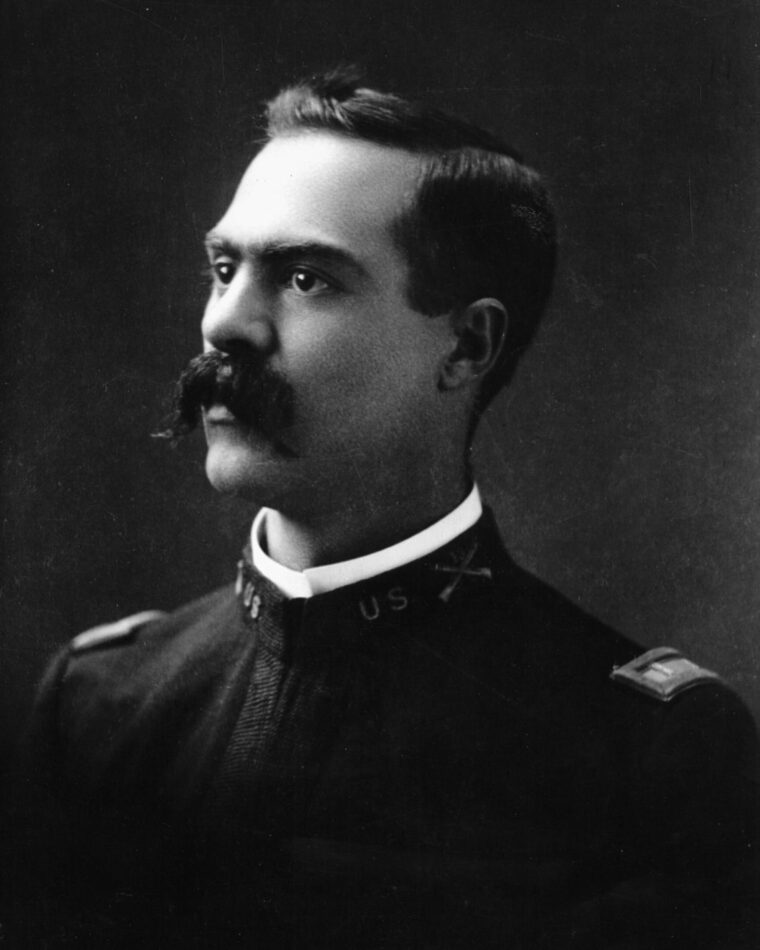

Not to be denied his part in the victory that lay ahead was a plucky, assertive young Army lieutenant who would take his destiny into his own hands. John Henry Parker had visions of Gatling guns cranking in his head, and he had a plan to make that vision work. Parker was born in Tipton, Mo., in 1866. He grew up on a farm, but at a young age he went to work for a printing company as a “devil,” or errand boy, and soon was publishing his own weekly newspaper in Calhoun, Mo. Wanting a taste of Army life, Parker turned the paper over to his partner, passed the entrance examination to West Point, and entered the United States Military Academy as a cadet in June 1888. Four years later he graduated 49th of 62 with the class of 1892. Ambitious and gifted, he applied himself to the study of law while still at the academy and was admitted to the Missouri bar in February 1896.

As a second lieutenant, young Parker paid his dues at obscure posts and continued his military education as a student officer. He joined the 25th Infantry Regiment at Tampa, Fla., on April 26, 1898, waiting impatiently with the rest of the invading Fifth Corps for the embarkation order to Cuba. Everyone had ample time to waste or use, according to his whim. Parker invested his idle hours in thinking and planning. He agreed with the prevailing military wisdom of supporting an infantry charge with artillery. At the time, the world’s armies still relied upon draft animals to haul and position the big guns—something not always possible given time, terrain, and mobility constraints. Looking ahead to Cuba, Parker considered the steamy, overgrown, up-and-down jungles of the semi-tropics and the logistical unfeasibility of getting bulky guns into action. He reached the conclusion that a new policy incorporating machine guns was needed to take the place of artillery at battle ranges closer than 1,500 yards. In 1898, this was quite a radical thought. Rapid-fire guns were nice to have protecting one’s position from assault, but in their all too brief history of actual combat they had yet to be offensively deployed.

For months before the war, Parker had written letters to the highest levels of the War Department, advancing his theory concerning the machine gun’s possibilities. Now, in Tampa, Parker conceived a plan to organize a special body of Gatling gun-equipped troops. He envisioned a mobile unit with the capability of supplying concentrated and controlled fire in a variety of offensive and defensive applications. To advance his plan, Parker proceeded up the customary chain of command. Unsurprisingly, he was passed from one skeptically unenthusiastic officer to the next, until he was granted an audience with Colonel Arthur MacArthur (father of World War II legend Douglas MacArthur), who happened to be in temporary command. Explaining the overlooked tactical possibilities of the Gatling, Parker offered to attend to the details of organizing his proposed unit. Somehow he was able to sell McArthur on the “moral effects” of such a unit’s presence in the field. After a brief deliberation, a few guidelines were set forth, and MacArthur gave Parker the authority to establish a new Gatling Gun Detachment.

Fifth Corps officially authorized Parker’s detachment on May 27, assigning him two sergeants and 10 privates. The hazardous nature of their duty was explained to the men, and they were given with the opportunity to withdraw. None did. The newly formed unit was given a warehouse to use for indoor drill. Despite the nightmarish logistical confusion and wholesale ineptitude of the Quartermaster Corps, four crated Gatlings were located on the seemingly endless string of box cars containing Fifth Corps’ supplies and delivered to the warehouse. Parker’s gun-handling drills consisted of repetitiously mounting, dismounting, and recrating the weapons until the troops were thoroughly proficient at the ritual. Instructions were given on loading and firing the piece.

Shafter Assembles His Gattling Gun Detachment

This familiarization and discipline continued until orders to board ship arrived on June 6. Parker felt that he was understaffed to inflict serious damage on the Spanish enemy, and brazenly asked corpulent commanding general William Rufus Shafter for an additional 20 men. Not only did he ask for the men, but he requested the privilege of selecting them himself. Remarkably, Shafter granted both requests. All members of the Gatling Gun Detachment were Regular Army, each chosen by Parker for their good character and sober habits. Many of Parker’s peers considered the new Gatling gun unit to be a crack-brained idea not worth the time or resources. Such authority handed to a subordinate lieutenant was the source of widespread resentment within the Tampa encampment. Some sneered that the Gatling gunners had received preferential treatment, and they weren’t wrong. Parker’s small detachment, now numbering 37 men, assumed the guise of an independent command. They ran their own well-provisioned mess, kept their own records, and answered only to General Shafter himself.

The disembarkation for Cuba proceeded in spite of itself. Despite only a four-hour notice, Parker had his guns dismantled, crated, and entrained on schedule while the balance of Fifth Corps was still milling around in the chaotic confusion that seemed to characterize the entire war. Parker’s crew boarded the Cuba-bound transport Cherokee, and the Gatlings were mounted on deck to afford the gun details further drilling opportunities during the wearisome journey. Another reason was precautionary: They might be needed to help repel anticipated attacks by Spanish torpedo boats.

No such attacks occurred, and the crossing was uneventful. Once in Cuba, difficulties in getting the Gatlings expeditiously unloaded and ashore were compounded by Parker’s low rank. The demands of superior officers took precedence. When Cherokee was ordered to remove herself from the wharf to make room for other vessels, Parker protested. Rather brashly, he sent word to Shafter that if he wanted to see the Gatlings unloaded, he would have to see to the matter himself. At 8 am the following morning, much to the consternation of the general’s staff, Shafter betook his 300-pound bulk dockside to attend to the unloading, just as Lieutenant Parker had demanded.

Once on land, the Gatling gunners suffered in the brutally oppressive Cuban climate and swampy, overgrown terrain. They were stung by Spanish bayonet plants and pinched by the ubiquitous sand crabs. One man fell victim to a scorpion. The detail cleared, by machete, a path for their mule-drawn gun carriages on washed-out foot trails that had never seen a wheel. After safely passing through the bad spots, Parker and his men impatiently waited for orders that might draw the detachment into the thick of the fighting to come.

Hopes rose on June 30, when Brig. Gen. Joseph Wheeler assigned the detachment a role in support of a planned artillery bombardment of Spanish positions. The next morning, Parker’s men were atop El Pozo Hill alongside the artillerists they were ordered to reinforce. The Gatling Gun Detachment was instructed to direct the multiple muzzles of their guns in such a manner as to sweep the 2,000-yard-distant hill, reportedly infested with Spanish regulars. Once again the junior officer had to endure the contemptuous and disparaging remarks of old-school cavalry officers still clinging to obsolete battlefield theories and calculating tactics from a yellowed Civil War playbook.

At dawn on July 1, the American battery commenced the artillery bombardment of the fortified Spanish outpost on the summit of the San Juan Heights. The Spanish responded with a barrage of their own, adjusting their smokeless-powder shells on the telltale, antiquated black-powder smoke of the American guns. What began as a long-range exchange of cannon fire quickly grew into a lopsided artillery duel, and almost instantly developed into a rout. Along with everyone else, Parker was ordered to retreat. Easing his guns into the descent, he was subjected to still more insults, these from the foot soldiers en route to assemble at the base of the heights. Meanwhile, the Spanish riflemen, snug in their rifle pits, opened a galling fire on the troops below, inflicting a frightful number of casualties. Soon Parker received his next order of the day, hollered over the din of battle: “Find the best place you can, and make the best use of your guns you can.” More a suggestion than a command, it afforded Parker some leeway in the application of his own tactics. Parker saluted, about-faced, and double-timed toward the sharp crackle of gunfire.

Determined to get into the thick of the fight, Parker advanced half a mile with his mules, men, and guns and forded the Aquadores River. From a level spot nearby, the enemy works atop San Juan Hill were clearly visible. At a gallop, Parker pulled his guns nearer to the front and found an advantageous position to set up shop. Thus began what Lt. Col. Theodore Roosevelt would later call his “crowded hour.” Parker, together with Roosevelt and hundreds of other brave men, would share this concentrated span of time.

Roosevelt’s Rough Riders and fragments of other volunteer and regular infantry elements were in the process of capturing Kettle Hill, a few hundreds yards to the northeast. At the base of the adjoining San Juan Hill, Parker and the rest of the contingent were hopelessly pinned down by Spanish Mauser fire. The Gatling Gun Detachment happened to be clustered with the 71st New York, which took heavy casualties. A regular officer braved the fusillade and dashed to Parker’s position. He directed that one of the guns and its crew go with him, and ordered Parker to take a position with the dynamite gun just across the San Juan River. The detachment sprinted their mules across the river, instantly unlimbered their pieces and, partially screened by a clump of underbrush, hurriedly set up their battery.

The Spanish Could do Nothing Against the Overwhelming Hail of Bullets

Immediately, they zeroed in on a Spanish blockhouse 600 yards away. Just as quickly, the Spaniards returned fire; two men from Parker’s small command of 37 fell dead from Mauser bullets. The remainder cranked the Gatling handles methodically and unceasingly, dropping a leaden .30-caliber rain on the Spanish entrenchments despite brutal return fire from the heights. In the distance, Roosevelt detected a “peculiar drumming sound.” He studied it momentarily, and after mistaking the racket for Spanish machine guns, recognized it for what it was. In his book The Rough Riders he remembered his inspired troops cheering lustfully when he proclaimed, “It’s the Gatlings, men. It’s our Gatlings!”

Parker now had the range perfectly. For eight and a half minutes, he incessantly hammered the Spanish with his Gatlings. Inspired by the rattle of friendly guns, the American forces rose to charge. The enemy, unable to withstand the hail of bullets, broke frantically from the safety of their trenches and were cut down by Parker’s battery, which coordinated its fire so as not to jeopardize the charging men. A mass exodus of thoroughly demoralized Spaniards, vainly trying to escape, evacuated their trenches, unable to return fire or repel the ascending force. As the Amerian volunteers and regulars swept upward, Parker covered their charge until it became prudent to call a ceasefire. The Gatlings had become so hot that their barrels glowed red. Rounds in chambers still loaded cooked off. The best testimony to the Gatlings’ effectiveness in softening the San Juan Heights came from a captured Spanish officer, who recalled, “It was terrible when your guns opened, always. They went b-r-r-r-r, like a lawn mower cutting grass over your trenches. We could not stick a finger up when you fired without getting it cut off.”

As soon as the American flag had been run up the pole atop San Juan Hill, Parker relimbered his guns, ran them up the hill, and immediately repositioned them. That afternoon, Parker and his Gatlings repulsed a feeble Spanish countercharge. The Rough Riders and fragments of six cavalry regiments cheered again. For the next 10 days, the Gatlings remained atop the strategic hill, now renamed Fort Roosevelt, immediately fronting the Spanish stronghold of Santiago, the most likely launching place of a retaliatory assault. They were dismounted from their wheeled carriages and fixed in the abandoned trenches, muzzles pointed in the direction of the town. Roosevelt placed two Colt machine guns and a dynamite gun under Parker’s command, giving him a battery of seven guns. During the occupation of the San Juan Heights, Parker proved his leadership ability. Roosevelt recorded approvingly, “At no hour of the day or night was Parker anywhere but where we wished him to be in the event of attacks.”

During the siege of Santiago, the Gatlings proved useful in disabling a heavy Spanish artillery piece, negotiated at a range of 2,000 yards. This marked the first time in history that an artillery gun had been destroyed by machine-gun fire. In putting the gun out of commission, Parker’s men also killed 40 Spanish soldiers. On July 11, Parker poured a leaden hail of 7,000 shots into Santiago, causing the Spanish occupants extraordinary anxiety. General Jose Toral, in his official statement to his own government, specifically mentioned the demoralizing fire as one of the prime reasons for surrender.

“Gatling Gun Parker”

In the aftermath of the Santiago campaign, Parker recommended the Medal of Honor for four members of his detachment. He himself was awarded the Silver Star for gallantry in action. The worth of rapid-fire weaponry had been proven beyond all doubt. It was now clear that a properly manned battery of machine guns was capable of independent action without the assistance of infantry, and could also supplant artillery in certain applications. In the postwar analysis, the machine gun’s offensive possibilities were an indisputable truth for military theorists and text writers to revise and adapt for modern warfare.

On August 15, the Gatling Gun Detachment boarded the Leona at Santiago, bound for Montauk Point, Long Island. Three weeks later, the unit was officially disbanded. After the war Parker, now famous across the land as “Gatling Gun Parker,” framed a plan to organize the machine-gun battery as a separate operational branch of the U.S. Army. The following year, he published a volume detailing his experience in Cuba. Prefaced by Roosevelt, History of the Gatling Gun Detachment demonstrated ably that Parker was equally adept with a pen as a Gatling. Parker published a second book, Tactical Organization and Uses of the Machine Gun in the Field, which became an international touchstone on the subject for years to come.

Now a captain, Parker served in various commissary and quartermaster posts until January 1908, when he was detached to organize the first Provisional Machine Gun Company of the U.S. Army. Among his duties was to write the drill, prepare a treatise on the tactical uses of machine guns, and devise the proper organization of machine guns within a regiment of infantry. Promoted to major, he joined the 24th Infantry at Columbus, N.M., in 1916, where he conducted a march into Mexico during which time the first use of trucks to transport infantry on campaign was undertaken. The next year he organized and conducted a school for machine-gun instructors and compiled the official training memorandum. He was now considered to be the world’s authority on machine-gun tactics.

In 1917 Parker was assigned to the staff of General John Pershing and accompanied the American Expeditionary Force to England, where he studied French and English machine-gun methods. He attended and conducted automatic weapons schools in Europe and wrote a revised machine-gun text that immediately became the new U.S. Army standard. Parker had a last taste of fighting in 1918, taking part in 12 battles and being wounded three times. He received several French decorations, among them the Croix-de-Guerre with palm for bravery at the Second Battle of the Marne. In earlier action, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for extraordinary heroism and a pair of Bronze oak leaves for daring leadership and personal courage in the face of a German artillery barrage of the trenches.

For his pioneering efforts in the field of machine-gun tactics, Parker was given the Distinguished Service Medal. Two years later, he was promoted to colonel. In 1921, he was stationed in his home state of Missouri as commander of Jefferson Barracks and later served as director of recruiting at Kansas City. After over 30 years of Army service, “Gatling Gun Parker” retired from active service on February 29, 1924. Together with a daughter, he moved to Reno, Nev., in 1940, where he divided his time between writing, YMCA activities, and helping to train Army personnel. He died in his room at the Reno YMCA, aged 76, on October 13, 1942. Military funeral services were held at the Presidio in San Francisco four days later. The eulogy delivered by Major William Anderson summed up Parker’s career quite succinctly: “His exploits in the face of the enemy were not even excelled by Sgt. York,” said Anderson. “He didn’t know the meaning of fear.”

Just a clarification; The Silver Star was not instituted until 1918 and there were no “retroactive” medals awarded for the SPANAM War. Parker may have been awarded on during WW1, but that would’ve first appeared as a silver star device on his WW1 Victory Medal.