By Eric Niderost

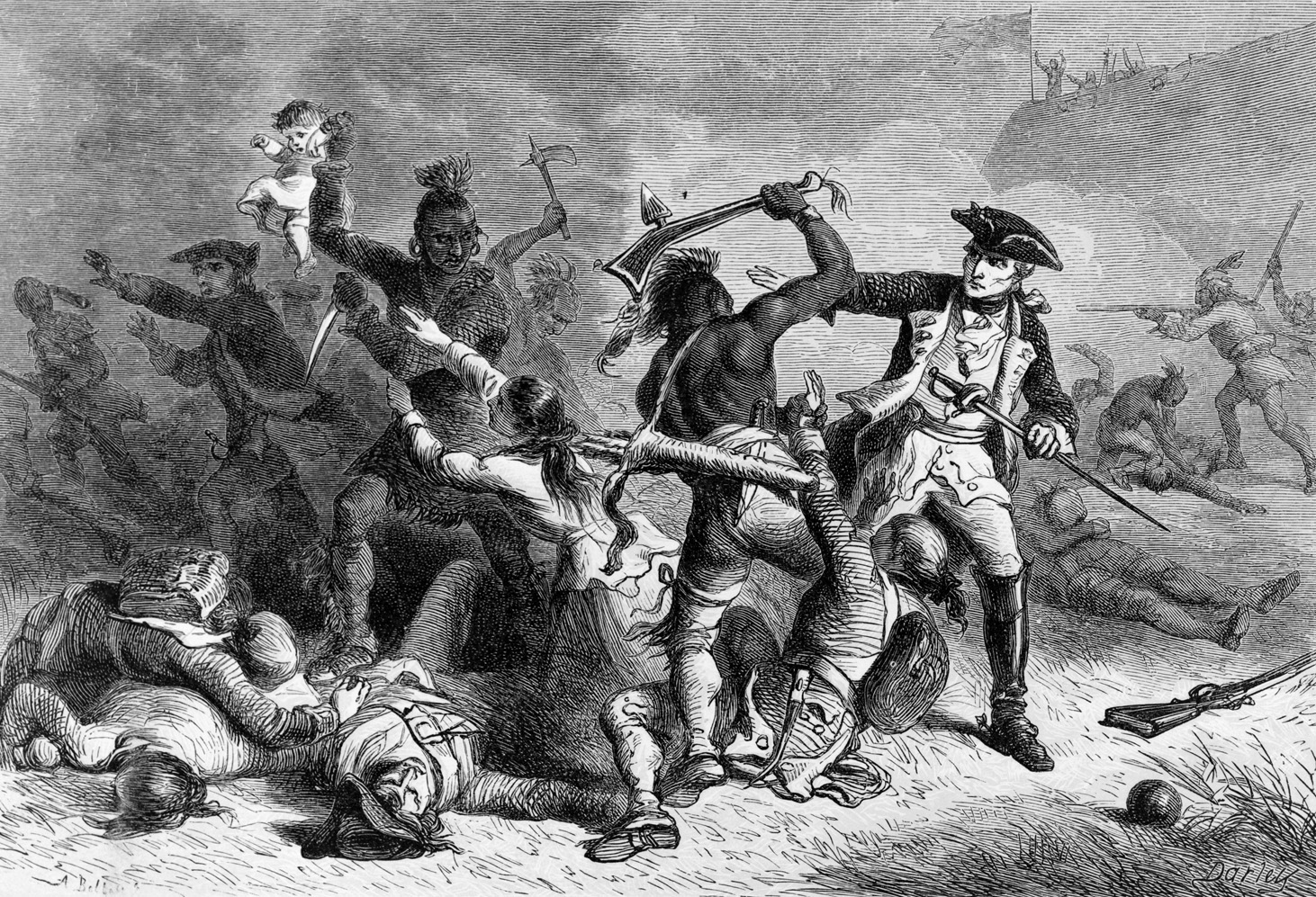

Sometime around 10 o’clock on the evening of August 1, 1798, spreading flames reached the magazines of L’Orient and ignited the tons of powder stored there. The French flagship was ripped asunder like a child’s toy, her massive hull seemingly vaporized in a wall of noise, smoke and flame. Tongues of fire leaped skyward, and the sheer force of the blast sprayed pieces of the ship far and wide.

A French officer’s sword was hurled from L’Orient, cascading through the air until it hit the bay with the speed of a javelin.

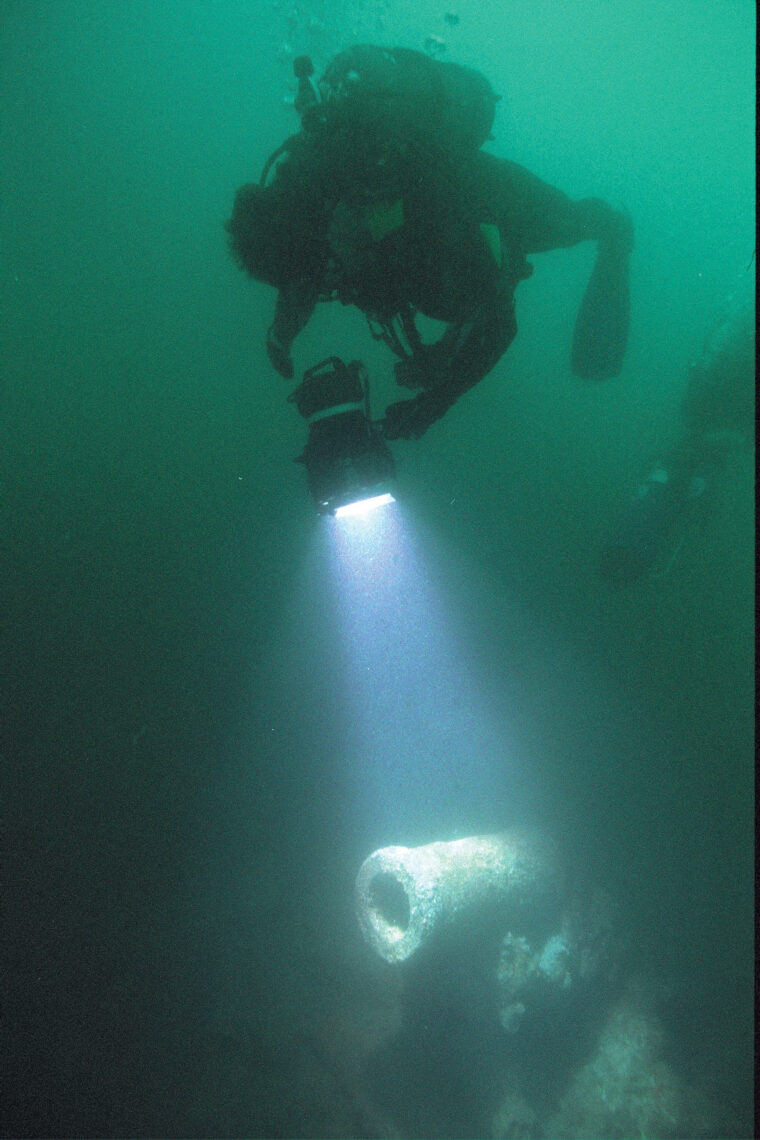

Slicing through the water with terrific speed, it hit the seabed with such force only the hilt and an inch or two of blade remained above the surface.

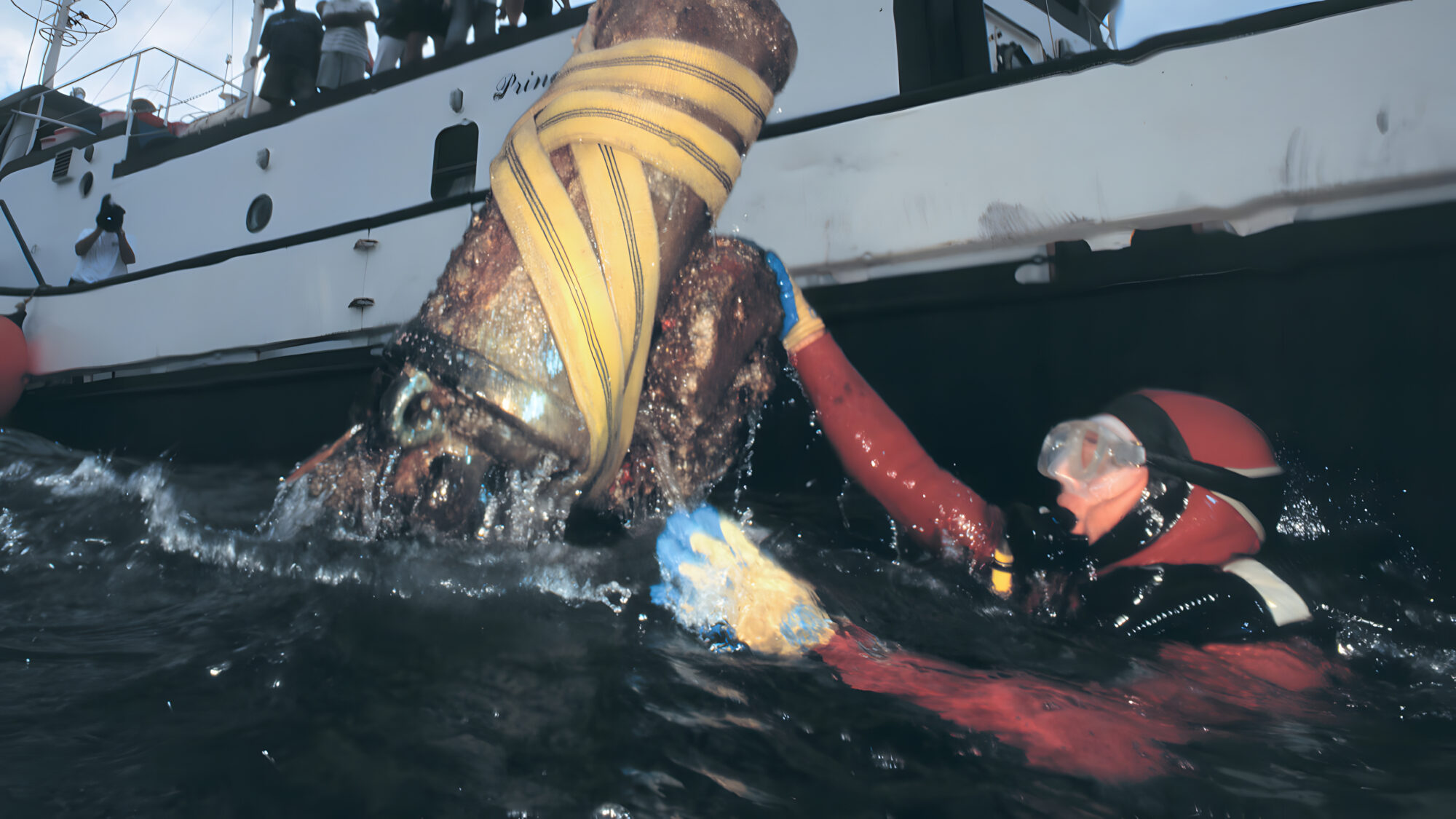

The sword remained in place for two centuries, encrusted with sea growths but still recognizable, until discovered by French marine archaeologists during the summer of 1998. The recovery of such relics as the sword provides new information on a famed sea battle that could be obtained in no other way. History is made more compelling because such objects are tangible links between us and the people of the past.

The project was an outgrowth of pioneering explorations conducted by the late marine explorer Jacques Dumas in 1983. Working with the French navy, Dumas managed to locate Napoleon Bonaparte’s flagship L’Orient and the frigate Artemise 40 feet below the surface of Aboukir Bay. His explorations were cut short by his untimely death, but the unfinished task was taken up by a young colleague, marine archaeologist Franck Goddio.

In some ways Goddio was uniquely qualified for the job. As he writes in the Foreword of the book Napoleon’s Lost Fleet: Bonaparte, Nelson, and the Battle of the Nile (Discovery Books, 1999), “My own fascination with this battle began when I was a boy growing up in France, where I used to spend vacations in the family home of descendants of Admiral Aristide Aubert Dupetit-Thouars, commander of the ill-fated Tonnant.”

In 1998 the Egyptian Supreme Council for Antiquities asked Goddio, now head of the European Institute for Underwater Archaeology, to return to the site. Goddio accepted, opening a whole new chapter on the study of the battle.

The wreck of L’Orient is spread over a quarter-mile square. Pieces of gilded wood give hints of how magnificent the stern must have been, and the skeletal remains of her great rudder, 36 feet long, convey an impression of how large the ship loomed. Cannon lay about the sea floor like tree trunks of a drowned forest, and 36-pounder shot is still stacked as if ready for use. In a remarkable example of survival, archeologists discovered rope still coiled around one of L’Orient’s bilge pumps.

Perhaps of even more interest are the personal effects of officers and men, objects that shed light into 18th century naval life. Officers were people of privilege as well as of responsibility, as L’Orient’s numerous artifacts plainly show. The finest French silverware was uncovered, as well as high-quality ceramic dinnerware. A brass bed warmer was found that must have warmed an officer’s bed during a chill night at sea, and a gold watch and chain obviously came from a man of some wealth and status.

Marine archaeologists uncovered some objects that have direct links to Napoleon Bonaparte himself. The general installed a printing press aboard L’Orient, and some of its lead type letters were found by divers. No doubt some of these very letters formed the words of Bonaparte’s grandiose proclamations; Napoleon’s first salvo in Egypt was with printer’s ink, not gunpowder.

Goddio and his team also uncovered a large number of gold, silver and copper coins. There were coins from France, Venice, Spain, Portugal and the Ottoman Empire. Some of the horde no doubt was loot taken from Malta, but there were even pre-Revolutionary French coins bearing the likeness of King Louis XV and King Louis XVI.

During the course of the underwater investigations, a number of new facts came to light. We now know, for example, that there were not one, but two almost simultaneous explosions aboard L’Orient that fateful night. When the large aft magazine exploded, it poured flaming debris on an auxiliary supply of powder in the bow. L’Orient’s bow and stern were pulverized in the twin blasts, leaving a shattered center section to fill with water and sink to the bottom.

Some crew remains were also found, including a cavity-ridden jawbone. The poor teeth bear mute testimony to the state of 18th century dentistry, and perhaps of diet as well. The remains will be buried on Aboukir (now Nelson) Island, where two hundred years ago the dead of both sides were interred. The French and British sailors will remain there, foes in life but reconciled in death.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments