By Vince Hawkins

In the Age of Reason, even wars were fought reasonably. Well-ordered marches, carefully dressed ranks of impeccably turned-out soldiers, and elaborately sketched battle plans were the order of the day in the so-called “lace wars” of the mid-18th century. The War of the Austrian Succession was no exception, although its bewildering array of diplomatic alliances may have seemed somewhat more confusing than usual, even for the various nations involved.

The eight-year war was the result of a simmering dispute over the rightful heir to the Hapsburg Empire. Charles VI of Austria, having succeeded to the throne on the death of his half-brother, Emperor Joseph I, and having no male heir himself, established the Pragmatic Sanction, a hierarchical understanding by which he laid down precisely the order of succession to be followed after his death. The Pragmatic Sanction specified that the Austrian crown should pass into the hands of Charles’s eldest daughter, Maria Theresa, and her rightful heirs.

The Fight for the “Cockpit of Europe”

Upon Charles’s death on October 20, 1740, Maria Theresa duly ascended to the Hapsburg throne, only to have her reign immediately disputed by Elector Charles Albert of Bavaria, King Philip V of Spain, and King Augustus III of Saxony, each of whom maintained his own legitimate right to the throne. In a swirl of claims and counterclaims, a coalition consisting of Austria, Great Britain, the Netherlands, and Russia formed to fight in favor of Maria Theresa against the allied forces of France, Prussia, Spain, and Sweden.

In April 1744, France officially entered the conflict by declaring war against Austria and her allies. Under the personal supervision of King Louis XV, a French army of some 90,000 men prepared to invade the Austrian Netherlands. At first things went well for the French, but in August Louis suddenly fell ill and all operations were halted, the army subsequently going into winter quarters. By the spring of 1745, the main French army, now under the command of Marshal Hermann Maurice de Saxe, was ready to try again. Saxe was determined to take the offensive and force the Pragmatic army into battle. In early May he took the main French army, some 74,000-strong, and invaded Flanders, the much-fought-over “cockpit of Europe.”

Constructing a Campaign Army

Saxe had spent months planning and overseeing every aspect of the forthcoming campaign. He had paid particular attention to his own army and its commanders. The French army, to date, had proven itself to be largely undisciplined and incompetent. After being mishandled repeatedly in battle, the army’s morale, even in the best of circumstances, was problematical. Saxe therefore had spent the better part of the autumn of 1744 training the army to a high state of readiness. He had drilled his troops as no French troops had been drilled in decades, driving them through repeated military maneuvers, target practice, and foraging details and transforming a previously inept army into a well-disciplined force.

In building his army for the campaign, Saxe had requested 120 first-line and 50 second-line battalions. Instead, he received only 89 first-line and 54 second-line battalions, many of the latter being composed of militia and local gendarmerie, troops of debatable fighting quality. Even though this put him at a numerical disadvantage in infantry, Saxe nevertheless was satisfied with the number of battalions at his disposal. He was even more pleased with the cavalry, 160 highly trained and well-mounted squadrons, which gave him a distinct superiority in that arm of the service. Going against established practice, he also employed several “free companies” of light, irregular troops, called Grassins, who were experts in the unorthodox tactics of skirmishing and guerrilla-style warfare. Although these units were universally regarded by most commanders with disdain and repugnance, Saxe was ahead of his time in recognizing their intrinsic value. He understood the effectiveness of their tactics and put great store in their fighting abilities. Finally, Saxe acquired 90 pieces of artillery and a corps of 2,000 sappeurs (combat engineers) to complete his army.

Of equal if not greater concern to Saxe was the quality and reliability of his generals, particularly the junior commanders. At age 47, Saxe was himself the youngest marshal in France and, as such, he often had to deal with older and more experienced, if not necessarily more qualified, subordinate officers. Many of these were hereditary nobles who, as “princes of the blood,” were entitled to the rank of lieutenant general; others were nothing more than the usual social parasites and hangers-on found in every royal court in Europe. The majority of these men were little short of useless and completely unreliable in all things military, but because of their station Saxe could not dismiss them outright and had to show due deference in his dealings with them. Fortunately, he was able to acquire the services of several capable and reliable commanders with whom he could offset the detriments of the royal layabouts. The most notable of these was General Count Ulrich Von Löwendahl, a Danish soldier of great experience and ability, whom Saxe appointed his second in command.

Outmaneuvering the Pragmatic Forces

In planning the upcoming campaign, Saxe had decided to undertake various ruses to lure the enemy into a situation militarily advantageous to him. Knowing that it would take the Pragmatic forces until June to marshal their entire army, Saxe moved quickly, reaching his headquarters at Maubeuge on March 31. The fact that Saxe was in Maubeuge raised many eyebrows at allied headquarters in Brussels. The Pragmatic leaders had believed that the French would first attack the fortress at Tournai which, along with Mons and Charleroi, was one of the key fortresses protecting the interior of the Austrian Netherlands, as well as forming the outer ring of defenses for the capital at Brussels. Although Maubeuge lay closer to Mons than Tournai, the allies could not afford to lose Mons, any more than they could afford to lose the other two fortresses. The French army, however, was positioned not toward Mons, but west of Maubeuge, stretched out in a semicircle that ended just beyond the French frontier. This seeming contradiction left the allies puzzled as to Saxe’s real intentions. To further obfuscate matters, by mid-April two French columns were detected marching toward Mons. To the allied council, this movement was a clear indication that Saxe intended to attack Mons—and soon. Accordingly, on April 23, the Pragmatic army marched out of Brussels to counter the French thrust.

The Pragmatic forces in Flanders consisted of British, Dutch, Hanoverian, and Austrian troops, totaling over 70,000 men in 103 battalions and 107 squadrons. The Dutch contingent was commanded by the Prince of Waldeck, the Austrian and Hanoverian contingent by Count Königsegg. The British contingent, as well as overall command of the army, was in the hands of Prince William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland. Cumberland was the second and favorite son of England’s King George II and, at the tender age of 23, held the imposing rank of captain-general, a title previously held by the great Duke of Marlborough. Unfortunately, Cumberland, despite his personal zeal and unquestioned courage under fire, had neither the military experience nor the tactical acumen necessary to command such a force, let alone the capabilities of a brilliant general such as Marlborough. King George II could, by royal decree, lavish distinctions on his favored son, but he could not make them a reality. The young Cumberland was about to test his mettle against one of the greatest military minds of the age.

As the Pragmatic army marched headlong toward Mons, Saxe, who had kept his forces in motion to deceive the allies, suddenly changed direction and swiftly moved the main army toward Tournai, his real objective all along. The French arrived outside Tournai on April 30 and promptly invested the fortress. By the following day, they had opened the first trenches and built pontoons across the Scheldt River. Saxe’s maneuvers had been so swift that the 8,000-man Dutch garrison was completely taken by surprise and caught unprepared. The governor of Tournai, who had been in Brussels conferring with Cumberland, was unable to return to his post before the French began their siege.

The allied army, having fallen for Saxe’s carefully planned deception, was left “swinging at the air” and chasing a decoy. Informed of the French presence at Tournai, Cumberland reluctantly realized that he had been duped and that his army was now out of position. He immediately moved to the garrison’s rescue, but with no good road from his current position to Tournai, he was forced to take his troops on a long, fatiguing cross-country march to reach the fortress. This unforeseen delay gave Saxe the time he needed to prepare the next phase of his master plan.

Setting up the Field of Battle

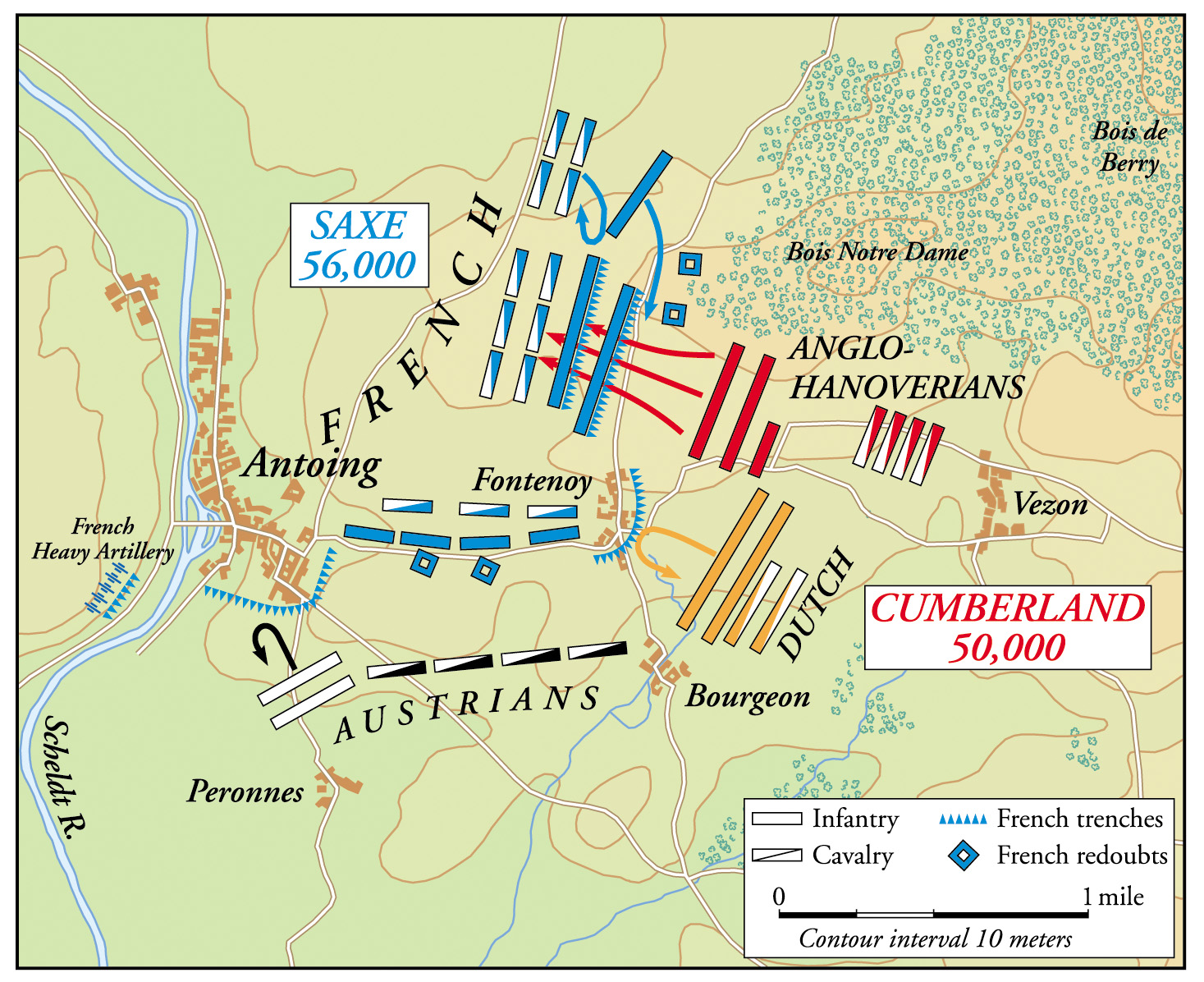

As Saxe had anticipated, the threat of besieging Tournai had roused the Pragmatic forces to the offensive. Confident that his operations against Tournai would bring the enemy to him, Saxe left 27 battalions and 17 squadrons—22,000 men in all—to continue the siege while he took the remaining 52,000 and moved to block Cumberland’s advance. He intended to position his army in such a way as to force the enemy to attack him at a disadvantage. Knowing that Cumberland would have to take one of two roads to reach Tournai gave Saxe the always crucial advantage of being able to choose the battlefield of his liking.

Saxe chose his ground with great care and deliberation, selecting an area near the village of Fontenoy, four miles southwest of Tournai. The plain around Fontenoy consisted of open, rolling meadows bracketed on one side by the Scheldt River and on the other by the Bois de Barry, a thick stand of woods. Saxe anchored his left flank at the village of Ramecroix, protected to its front by some swampy ground and the Bois de Barry. He placed his right at the village of Antoing, on the Scheldt, and his center around Fontenoy. Saxe’s line ran west from Antoing, facing south, along the road to Fontenoy, where it then turned sharply north, then west, to the Bois de Barry and eventually the village of Ramecroix. The natural obstacles of the Bois de Barry and the village of Antoing created a kind of funnel, channeling approaching troops into the plain and directly toward the village of Fontenoy. This disposition, however, meant that the French had their backs to the Scheldt, a dangerous position should the army be forced to retreat. The seeming vulnerability of the position was a calculated risk on Saxe’s part, a gambit he hoped would entice the British to attack directly into his guns.

To further solidify his line, Saxe ordered his 2,000 sappers to build five redoubts along the front of the French position. These redoubts, square wooden stockades, were each supplied with four cannon and a contingent of infantry and positioned in such a way as to break up an enemy attack. They were also placed far enough apart to allow French troops to counterattack between them. Three of these redoubts were between Antoing and Fontenoy, positioned to secure the line between the two towns. The fourth redoubt lay at the corner of the Bois de Barry to cover the area between the woods and Fontenoy. The fifth was positioned near Ramecroix to protect the approach through the Bois de Barry and support the fourth redoubt. The fourth and fifth redoubts were the most important. Named respectively, Redoubt d’Eu and Redoubt Chambonas, after the unit occupying them and the colonel commanding, they were situated along the edge of the Bois de Barry, their guns sighted to enfilade the flanks of any advancing force. The woods in front of Redoubt Chambonas had been cleared to allow its defenders an unrestricted field of fire, and the felled trees were used to create abatis.

Antoing and Fontenoy were also carefully prepared for defense. As Fontenoy lay in Saxe’s center and was therefore of major importance, much of the town was leveled and fortifications constructed amongst the rubble. The guns placed in the redoubts and the towns would bring any approaching enemy under a devastating crossfire. Saxe had another reason for building these fortifications, that of steadying and encouraging his inexperienced troops, especially against the renowned and lethal musketry of the British.

The French Lines of Battle

By May 8, Cumberland’s exhausted force had finally arrived and was taking a much- needed rest in a temporary camp. Meanwhile, his own lines prepared, Saxe marched his army into position, deploying his 66 battalions, 129 squadrons, and 90 guns to meet the enemy. Cognizant of both British military tradition and Cumberland’s seniority, Saxe knew that the British troops would be deployed on the Allied right, the post of honor. He therefore positioned his best troops on his left. On the far left of the line he placed a small regiment of Corsicans, followed by six battalions of the “Wild Geese” Brigade, Irish mercenaries in French service, with eight guns. The Irish, deployed behind wooden breastworks between the Chambonas and d’Eu redoubts, were positioned to either prevent the British from debouching outside the Bois de Barry or, if necessary, form a reserve for the exposed French center.

In the Bois de Barry, Saxe placed some of his light, irregular troops, the Grassins, a mixed regiment of horse and foot. They would block any attempts to penetrate the woods and harass the flank of any troops marching past the woods. Next to the Irish were the battalions of the Swiss Guard. In the center, Saxe placed seven battalions of the French Guards along a sunken road. Since the Guards would bear the brunt of the main attack, Saxe placed a second line of five additional infantry regiments behind them as support. As further insurance, Saxe put a special detachment of four battalions in the village of Rumignies, under the command of Count Löwendahl. At the Scheldt River bridgeheads he positioned seven battalions and four cavalry squadrons. Along with these two special brigades Saxe placed 12 guns. The bulk of his cavalry, some 60 squadrons, was deployed in two lines behind his center and left.

The French line hinged on the village of Fontenoy, and this important linchpin Saxe packed with artillery supported by elite troops. The line from Fontenoy to Antoing was protected by three of the redoubts into which Saxe previously had placed cannon and infantry. Instead of connecting the redoubts by means of trenches, which he personally abhorred, Saxe deployed 19 squadrons of cavalry to hold this part of the line. Lastly, across the Scheldt and positioned to enfilade any force attacking the right of his line, Saxe placed a battery of six 12-pounder field guns near a mill.

Saxe’s Distractions

With his dispositions complete, Saxe normally would have focused all his attention on the upcoming battle, but he had been presented with another paramount concern—that of the royal personage. King Louis XV had arrived in camp on May 7, along with his son, the 15-year-old dauphin, Louis. The king had also brought with him a contingent of Swiss Guards, a swarm of court lackeys, valets de chambre, a large baggage train, and several important state officials, not least of whom was the Duc de Richelieu. While the presence of the king gave a welcome morale boost to the troops, it proved somewhat more problematical for their commander. Saxe now faced the added distraction of protecting Louis from injury or capture, both a distinct possibility in the present circumstances. He also had to tolerate the annoyance of having his battle plans and orders questioned and critiqued by the king’s retinue of failed commanders and amateurish court generals, seemingly all of whom were predicting a major military disaster.

To compound these concerns, Saxe was suffering terribly from dropsy, an illness that causes the limbs to swell with fluid and induces profound lethargy. Unable to comfortably mount a horse, he had to be carried about the field in a wicker chair. In the past months, he had twice undergone the painful procedure of having his abdomen punctured to drain the excess fluid and reduce the swelling in his limbs. Despite all this, Saxe had completed his preparations and stood ready for the coming battle.

Cumberland Assembles his Forces

Cumberland, unsure as to the exact strength and location of the French army, rode out from camp on the evening of May 9 with his staff to ascertain the enemy’s whereabouts. A post-battle account by an unidentified British officer in Gentleman’s Magazine described the duke’s nighttime scouting foray: “The generals went in the evening to observe them, and could discern easily several of their squadrons, which were separated from our army by a country divided by a little rivulet on our left, and by underwood, copses, and hedges, which they had filled with their pandours and grassins, and supported them by several little squadrons drawn up on the plain, which rose by an easy ascent to within a little distance from their camp, which was situated at the top of that rising, beginning at Antoin[g], leaving the village of Fontenoy in their front, and extending itself toward their left near a large wood, which was beyond the village of Vezon towards the center of our right. This village was also possessed by the enemy, and covered by small squadrons, placed at little distances from each other. As we could not get into the plain, which was between their camp and the defiles on our side, without first driving them from their little posts; and as it was late, it was then resolved to put off this attempt till next morning.”

On the afternoon of May 10, Cumberland’s army left camp and began its advance on the enemy. French pickets occupying the outlying villages immediately set fire to houses and barns, a sure sign that the enemy was approaching. The smoke alerted Louis XV of the approaching danger, and he immediately ordered the army into motion.

Cumberland was somewhat surprised to find that the French were not falling back before him, but apparently had decided to stand their ground. He was convinced, however, that the superiority of British firepower would win the day, as it had at Dettingen two years earlier. Besides, aware that Louis XV was on the field, Cumberland saw a God-given opportunity for personal glory in both defeating the French and capturing their king. He therefore ordered detachments to clear the plain of French troops so that the main army could deploy for battle. The anonymous Gentleman’s Magazine account described this maneuver: “Accordingly on the 10th, six battalions and twelve squadrons, with 500 pioneers, six pieces of cannon, and two howitzers, were commanded from each wing for this service, which was performed with great ease, the enemy having been driven to the very top of the rising near their camp where they stood drawn up, as well to observe us, as to cover the dispositions they were making behind that line; his royal highness, the marshal and prince Waldeck, went upon the plain, and having examined the ground, we returned in the evening to our camp, after we had seen the enemy burn a little village somewhat short of Fontenoy, which they had fortified. We left the detachments at the posts they had taken, and the order was given for attacking the enemy in the morning.”

The right wing had taken fire from the irregular forces in the Bois de Barry, and Lt. Gen. Sir James Campbell strongly advised the duke to clear the woods of enemy troops before attacking the following morning. veteran field marshal Königsegg, recognizing the strength and advantage of the French position, counseled against such an attack, urging Cumberland to withdraw instead and attempt to outflank the enemy. Cumberland refused both suggestions. Clearing the Bois de Barry could take all day, and he had no intention of becoming embroiled in forest fighting, apparently recalling Marlborough’s nightmarish struggle for the woods during the Battle of Malplaquet in 1709. At the same time, he adamantly refused to retire in the face of the enemy, resolving instead to drive them from his front. Cumberland was further advised to launch a massive cavalry attack around the Bois de Barry and strike at the French left flank, but he cancelled this plan when allied troops drew fire from the southern edge of the woods. Cumberland was resolute—or supremely stubborn. The army, he said, would attack early the next morning.

Day Break Opens with Cannon-Fire

Cumberland ordered the main attack to begin the next day an hour before dawn. Not having had time to form the entire army before striking out for Mons, Cumberland’s force for the battle numbered only 46,000 men in 56 battalions, 87 squadrons, and 78 guns. Although Cumberland fancied himself a great soldier, his plan of attack was incredibly simplistic. The attack would be a three-pronged assault against the French position. Brig. Gen. Lord James Ingoldsby, with four good battalions and three 6-pounders, would attack and clear the Bois de Barry, then take Redoubt d’Eu on the right. The Dutch, under the Prince of Waldeck, would attack the village of Fontenoy in the center and, supported by Field Marshal Königsegg’s Austrian cavalry, take the village of Antoing on the left flank. On the right center, Lt. Gen. Sir John Ligonier’s British and Hanoverian infantry, screened by 15 squadrons of Lt. Gen. Sir James Campbell’s cavalry, would form two lines and launch a massed attack against across the open ground between Fontenoy and the woods. If Cumberland could pierce the French center, he could then attack Fontenoy from behind, roll up Saxe’s line, and trap the French against the Scheldt. Essentially, Cumberland was going to do exactly what Saxe had prepared for and march straight into the mouth of his waiting guns.

Cumberland had the army up and on the march by 2 am, moving out of their camp in three great columns. The first, comprised of cavalry, marched by the road to Mons along the Wood of Vezon. The second, made up of infantry, marched through the village of Vezon. The third moved over the plain between Fontenoy and Antoing. The three columns were very slow in forming, and French artillery “incommod[ed] them extremely.”

Dawn broke at around 5 am on May 11 to find the fields around Fontenoy shrouded in a gray morning mist. French gunners, however, had a clear enough view to open the battle by firing on the British cavalry forming to their front. The first hint of what lay in store for the British that day then occurred. Richard Davenport of the British Horse Guards recalled: “We marched from our camp, which was about two miles from the enemy … at the break of day, the right wing, viz. the British and Hanoverian troops, through Vezon, which was a village we had taken possession of the night before, and formed in a plain to the left of it. The enemy’s artillery played very briskly for some hours from three batteries whilst the troops were forming and General Campbell had his leg shot off.” Mortally wounded, Campbell was taken from the field without ever having informed any of his subordinates of Cumberland’s orders. Without their commander and with no orders to withdraw, the British cavalry stolidly stood their ground for over an hour while French gunners raked them with fire.

Eventually, General Ligonier formed his infantry into the two lines and returned fire on the French. Cumberland ordered seven cannon advanced to the head of the brigade of guards, which managed to silence the moving batteries of the French. The British artillerists also scored an early triumph of their own, shooting off the legs of the Duc de Grammont, who died about an hour later. While the death of the vainglorious Grammont, a colonel of the French Guards, was of minor consequence to Saxe, the same fire also killed his most trusted artillery commander, Henri du Baraillon du Brocard.

The artillery duel raged until 9 am, by which time Ligonier told Cumberland that he was ready, if the duke approved, to attack the enemy as soon as Prince Waldeck marched into the village of Fontenoy. In his journal, the prince recalled the difficulties encountered by the British: “Since the English and Hanoverian detachments were not sufficiently advanced the previous day, they had such a narrow front that it was a very long time before they could be put into battle. Thus I had to retire two battalions on the right of our second line and sent them to fill the gaps which were still on the left, and it was only around 9 o’clock that I urged general Ligonier to go forward with the right wing, and then I made the left wing march, after they had fixed bayonets. Around 9 o’clock, all our army moved off at the same time; our right was going to attack the left of the enemy and the first redoubt which was at the point of the wood of Barry; our center, where the Hanoverian infantry were, and the twelve Dutch battalions that I led myself, was to attack the village of Fontenoy, and the remainder of the left wing advanced with M. Cronström until they were within long musket range of the enemy. The right wing pushed the enemy first, chasing him from the sunken road, and seized a few pieces of cannon, but the fire from the redoubt that they could not take, and from one of the batteries of Fontenoy that took them in flank, obliged them twice to retire.” Waldeck’s account is supported by the French Journal, which reported: “The cannonade lasted until nine o’clock, when they moved to attack us. They began by making two successive attacks upon the village of Fontenoy in both of which they were vigorously repulsed.”

The Pragmatic Forces Falter

Saxe’s plan was working to perfection, the enfilade fire from the guns in Redoubt d’Eu and Fontenoy mercilessly hammering the British lines. Davenport confirmed the devastating effectiveness of the French artillery. “Our cannons fired briskly on their batteries, which appeared to be silenced and the troops marched up to their entrenchments in good order and with a seeming appearance of victory,” he wrote. “Suddenly the French opened with two fresh batteries, one from a wood to the right and the other from the village of Fontenoy to the left, which played incessantly during the whole engagement and destroyed great numbers, the two batteries being less than a mile from one another. The Horse were equally exposed to the cannon with the Foot.”

Cumberland, seeing his attacks repulsed and his right flank exposed to a terrible enfilade fire from the Bois de Barry and the redoubt that Ingoldsby should have taken hours earlier, rode off in a fury to find the dilatory general and demand an explanation. Ingoldsby, who had attempted to follow Cumberland’s orders to “take that redoubt yonder at the point of the Wood,” had his advance greeted by severe fire from Saxe’s Grassins, hidden in the Bois de Barry. The Grassins excelled at this type of irregular skirmish warfare and so confounded Ingoldsby that he angrily exclaimed, “God knows how many of them!” Their deadly accurate fire, combined with that of the artillery in the redoubts, shattered Ingoldsby’s advance, and he fell back to the safety of a hollow on the outskirts of the woods. It was there that Cumberland found him, cowering with his men under the guns of Redoubt Chambonas.

Ingoldsby knew that if he tried to advance into the ground between the two redoubts his men would be torn to pieces. No amount of berating or threats from Cumberland could induce him to advance. Redoubt d’Eu would continue to stand and pour its deadly fire into the front and flanks of any troops advancing across the open ground near Fontenoy.

Things fared no better with the rest of the army. The Dutch and Austrians were also repulsed at the front with great loss of life. Prince Waldeck had an equally difficult task in attacking Fontenoy. “They had put entrenchments around the cemetery of this village, of which the situation was already very advantageous,” he recalled. “In that cemetery, there were four batteries of cannon and some infantry, and behind this village several lines of infantry. Between Fontenoy and the borough of Anthoing [SIC], they had built three fleches [redoubts] which were furnished with artillery. In front of those fleches ran a sunken road, almost from one village to the other; the depth of this road, which was filled with infantry, diminished on approaching Fontenoy…. The center first cleared the enemy from every house that was around the cemetery, upon which were made several useless assaults. While the assault was in progress, I sent one of my aides de camp with orders to M. Cronström, who was on the left of our infantry, to advance with the eight battalions and to chase the enemy from the road which was in front of the fleches, in order to give an opening to our cavalry to attack the enemy position. The terrific fire that emanated from those fleches and from the village of Fontenoy, which took them in the flank, prevented them from advancing. I ran there to oblige them to advance and so ordered M. Cronström, who began to move off; but since the main thing was Fontenoy, I returned there in order to encourage this attack, and in order to make it with more success, the battalion of my first regiment came from the reserve and someone also sent the Scots Highlanders.” These Highlanders were the newly raised Black Watch, the 43rd Regiment of Foot. The Highlanders, who were engaging in their first battle, attacked with the Dutch against Fontenoy of their own accord. Despite their courage and tenacity, this second attack also failed to take the village.

In the meantime, Austrian cavalry on the left wing made a move to attack the French right, but they had been so rattled by enemy cannon fire that the first movement of the French cavalry caused them to retire in great disorder. Meanwhile, the Dutch and Austrians attacking Antoing were repulsed so badly that they fell back behind a hill line and remained there, out of the fight, for the rest of the day. These two futile attacks cost Waldeck some 1,450 casualties.

These failed assaults, for the most part, can be blamed on Cumberland’s inexperience. The allied artillery, with a few minor exceptions, had remained largely silent all day. Cumberland had not had the foresight to bombard the French positions, their redoubts, and the fortified villages of Fontenoy and Antoing before sending in the infantry. Consequently, the allied troops had been subjected to a fierce French artillery bombardment that had been raging almost ceaselessly since 5 am.

Saxe Commands from the Front

Saxe, who had been carried about the front all morning in a wicker chair, had started the battle feeling extremely ill and had been forced to suck on a metal musket ball to slake his burning thirst. He now sat smiling, noting with satisfaction that his positions, especially at Fontenoy, had held up well against repeated enemy attacks. Saxe knew, however, that the battle was far from over, and he brushed off congratulations for having repulsed the Dutch attacks at Fontenoy, stating, “All is not said; let us go to the English, they will be harder to digest.” Abandoning his chair, Saxe painfully mounted his horse and rode to the center of the French position to personally direct operations.

With his original plan shot to blazes, Cumberland was left with only two options, neither particularly palatable: either continue to advance under severe flanking fire or withdraw and seek a better opportunity later. Ever headstrong, Cumberland opted to attack again and set about launching one last massive assault against the French center. A central breakthrough spearheaded by 17 British battalions, the best units in the army, utilizing their superior firepower, would surely be able to force a hole in the French line, he reasoned. Cumberland drew his British troops up into two lines, 10 battalions in the first and seven in the second, with the remnants of Ingoldsby’s battalions securing their right flank and a few manhandled guns accompanying the column. The Hanoverians, lacking for space on the left of the English, were forced to make up a third line to the rear. They were followed in turn by the cavalry, which also had no room to deploy forward.

Despite the vigorous protestations of Ligonier and Königsegg, Cumberland resolved to vacate his position as commander-in-chief and personally lead the attack. Once again, his inexperience caused him to chose martial ardor over military soundness. As if to underscore this point, he set a deliberate cadence for the advance, barely 1,000 yards per hour, and ordered the men not to return fire until they were within 30 paces of the French. It almost seemed as though he were daring the French gunners to shoot down his men.

The French Counterattack

At around 1 pm, Saxe realized that the battle had reached its climax. With the British stalled deep within the French lines, out of range of support from the rest of their army, and totally on the defensive, now was the time for the counterattack. Turning to Löwendahl, Saxe called out: Right! Now for the final heave!” Assembling every available regiment whose morale could still be relied upon, Saxe threw the seven battalions of the French and Swiss Guards, along with the five Irish regiments of the “Wild Geese” Brigade into the counterattack. A battery of four guns from the reserve was also brought forward to pound the front of the British “box,” which now was taking artillery and musket fire from all sides.

With a furious rush, the French troops went for the British, charging straight into the boxed formations with bayonets lowered. Prominent amongst them were the members of the Irish Brigade, who had a distinct score to settle with their longtime British antagonists. With thunderous cries of “Cuimhnigdh ar Liumneac! [Remember Limerick!],” the self-described “Exiles of Hope” threw themselves against the British with a ferocity born of pure vengeance. Stunned by the savageness of the counterattack and worn to the point of exhaustion by over nine hours of fighting, during which time they had been remorselessly pounded by artillery and harassed by cavalry attacks, the British finally gave way around 2 pm and began to fall back.

A Fighting Retreat

Although they were now in retreat, the British still did not completely break. The iron-disciplined battalions stood firm and covered the retreat, delivering fierce, point-blank volleys into any French units that pushed them too closely. The withdrawal was also well covered by the British cavalry, particularly the Life Guards and the “Blues” of the Household Cavalry, who finally had room to maneuver and rushed to make up for lost time. As the British infantry began their withdrawal, the commander of the Life Guards, the Earl of Crawford, told his men, “Gentlemen, mind the word of command and you shall gain immortal honor.” The Command was to charge, and the Life Guards and Blues did so repeatedly, holding in check the pursuing French army until the British infantry was safely away. Afterward, Crawford removed his hat, saluted his men, and thanked them, saying, “You have acquired as much honor covering so great a retreat as if you had gained the battle.”

In spite of the last-gasp valor of the British it was clear that Saxe and the French were the undisputed masters of the battlefield. On the other side of the field, Prince Waldeck was also trying desperately to withdraw his forces in the face of the French advance. “I ordered first the removal of the artillery, but most of the horses had been killed or ran away, so taht it was necessary to reclaim it by hand, a very lengthy and difficult piece of work, since the terrain was very uneven,” he recalled. “In the meantime, I received a small note from the Duke in which were these words: ‘My Prince, I retire beneath the cannon of Ath;’ signed; ‘William.'”

The Cost of Battle

Learning that Cumberland was retreating toward Ath, Saxe immediately sent the Hussars and Grassins galloping after him. The horsemen fell on the British rear guard without pity, driving it before them in complete disorder and carrying off a great number of wounded officers whom they found abandoned in houses alongside the road. Lt. Gen. James Campbell, the most senior casualty, was discovered lying dead in the village of Bauginn. When Cumberland at last reached the safety of Ath, he burst into a violent fit of crying. His French counterpart had a similar reaction to the outcome of the battle. When Louis XV went to congratulate Saxe on his stunning victory he found the marshal prostrate in the dirt, his lips awash with yellow sputum, weeping piteously. After he had recovered sufficiently to speak, Saxe fell to his knees before the king and, blinking back tears, exclaimed, “Sire, now you see what war really means.”

When asked later why he did not further pursue the shattered British infantry, Saxe said simply, “We had had enough.” Casualties for both sides were high. The allies lost around 10,000 killed and wounded, of whom about 7,500 were British and Hanoverians, while French losses were 7,200 killed and wounded. Cumberland’s command staff was also hard hit, with one major general and one lieutenant general killed, and one major general, two brigadier generals, and two aides de camp wounded.

One of the wounded brigadiers, Ingoldsby, would face a court-martial for failing to execute Cumberland’s order and take Redoubt d’Eu. Ingoldbsy would be found guilty of a gross failure of judgment and receive a three month suspension from service. At the end of that time, he was to be reinstated and given his commission as major general, which the king had already signed. Upon his return to England, however, Ingoldsby found that he had been stripped of his standing majority in the guards, and he was required to sell his infantry company at a loss- all without so much as the pretense of a second trial.

The French Army Revitalized

Following the battle, it was noted by many in the French army that the last time a French king and his son had served in the same battle was at Poiters in 1356, an English victory. Fontenoy was the first time a French king had presided over the defeat of an English army in the field. Saxe, too, had won the day, achieving heroic status in France and establishing a permanent reputation as one of the age’s leading military commanders. His brilliantly conceived offensive plan had gained him the initiative and enabled him to set the pace and course of the campaign from the very outset. Cumberland’s only option was to react to Saxe’s initiative and dance to his opponent’s tune.

Fontenoy was the spark that gave the French army a much-needed burst of momentum. After Fontenoy, Saxe swept through Flanders, capturing several key cities by the end of the year. Shortly after his triumph at Fontenoy, Saxe wrote to his brother, with understated satisfaction, “It is very sweet to win battles.” A classic example of the technical style of 18th century warfare, Fontenoy remains best known for its epic grandeur. It was, without a doubt, the epitome of the century’s “lace wars,” an ironic combination of rationality and violence which made the Age of Reason also, sadly, the Age of Battles.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments