By Peter Zablocki

At around 9:30 p.m. on August 25, 1939, a German Opel staff car burst into the courtyard of the temporary headquarters of the Abwehr (German Military Intelligence) near the Slovakian and Polish border. The young staff officer, Heinrich Gaedcke, nodded at two plainclothes agents as he entered the inconspicuous country home.

The orders to cancel the invasion of Poland, Fall Weiss (Case White), set to begin at 4:30 a.m. the following day, had come through to Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, chief of the supreme command of the German armed forces, personally from Adolf Hitler just a couple of hours earlier. The phone switchboard operators worked frantically, passing the orders down as far as local regimental and battalion levels. But circumstances and world events were changing at a rapid pace. Hitler had received the bad news at 6 p.m. that his hope of a continued British and French policy of appeasement had evaporated. After being notified of a new British and Polish treaty guaranteeing the former’s help should Germany attack the latter, a furious Führer ordered Keitel to “Stop everything at once!”

While Keitel’s staff reached all military units in time, the HQ could not get Abwehr Secret Service Director Wilhelm Canaris because of his intelligence agency’s clandestine method of operations and frequent relocation. Canaris oversaw the Brandenburgers—the German special forces tasked with secretive and delicate sabotage missions across the Polish border.

“The Fuhrer has called off the invasion of Poland on political grounds,” the panting young man blurted to Canaris. “You must do everything possible to halt your combat teams!”

The man who would soon turn against Hitler and funnel top-secret information to the Allies seemed unfazed. By September 1939, Canaris had already made up his mind to resist the Nazi leader’s world conquest, a decision that would lead to his execution in 1945. Canaris was pleased at the prospect of Hitler indefinitely postponing his plans to attack Poland in light of the British resolve. The cancellation order went out immediately, but in the rush one Brandenburger group was missed—with historical consequences.

When Canaris was informed later that Lt. Dr. Hans Albrecht Herzner’s covert operation across the Slovakian and Polish border had already left, Canaris sent his scouts to find Herzner and his commandos before an international incident was created.

Miles away, Herzner jotted down a message in his notebook. “Generalkommando VIII, Crossing Polish Border…at 00.30 hours, near point 627 north-northwest of Cadca.” Dr. Herzner and his band of 24 irregulars were going to war—on their own.

Hitler’s attack on Poland was a foregone conclusion as early as 1938 when he introduced his policy of “Heim ins Reich” (Back to the Reich). The Nazi leader made clear his goal to reclaim all ethnic Germans living in other countries, particularly those in Eastern and Central Europe, which gained land at Germany’s expense after World War I. After the annexation of Austria and the Sudetenland, followed by the occupation of Czechoslovakia, Nazi attention turned to Poland. Hitler was sure the British and the French wanted no repeat of the Great War. In his mind, they would never risk a global conflict over the Central European nation, just as they had not stopped him from carrying out his Heim ins Reich policy up to that point.

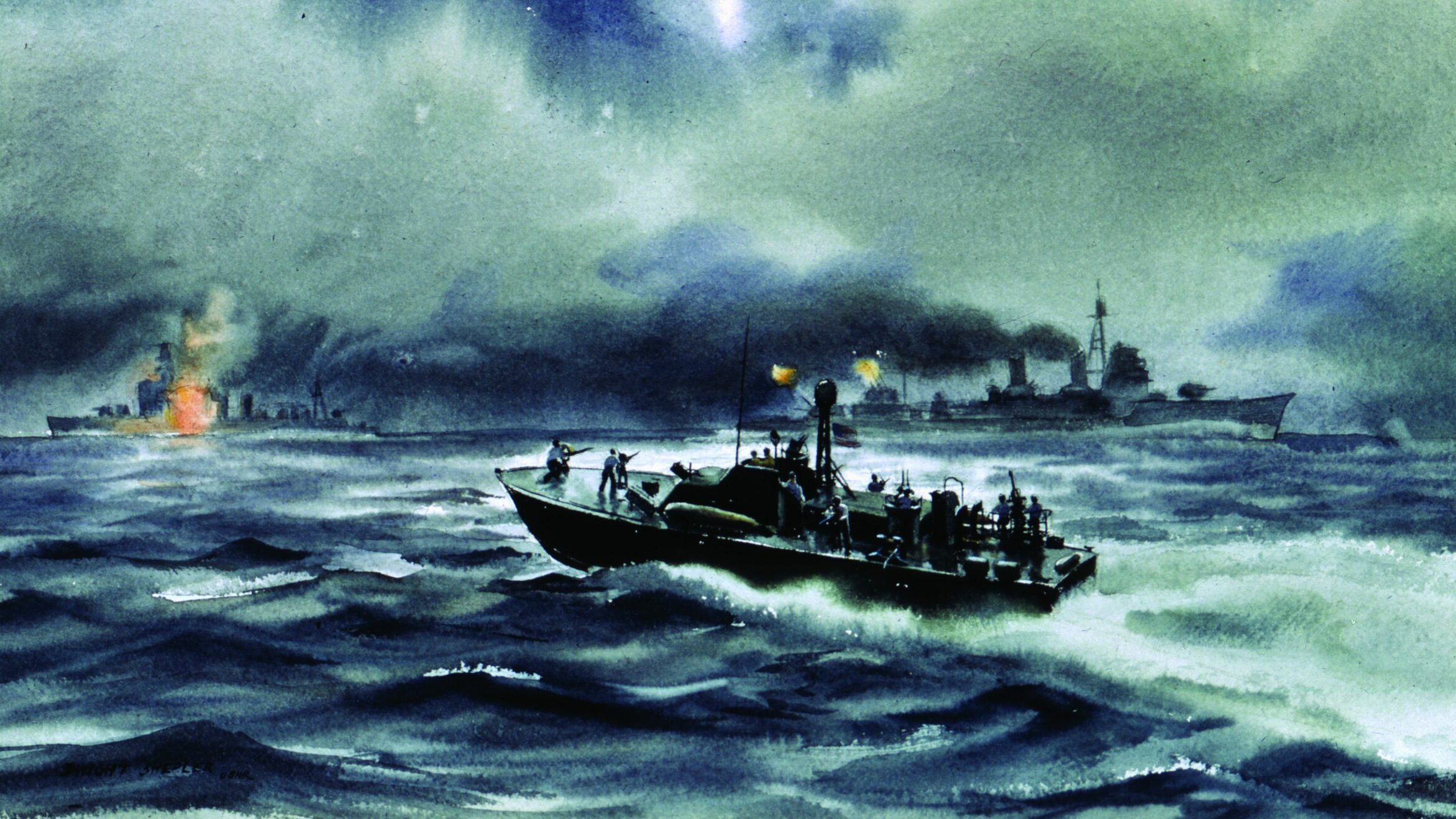

Hitler’s last assurance of an unimpeded takeover came to fruition on August 23, 1939, with the German-Soviet non-aggression pact openly suggesting that the Soviet Union would remain neutral during any German incursion into Poland. The secret protocol calling for a division of the nation shortly after the German invasion would ensure that. The orders to prepare for a full-scale attack on Poland went out to the Army, Navy, and the Luftwaffe that same day. Fall Weiss would see German forces attack Poland on multiple fronts. By the morning of August 25, 1.5 million men awaited Hitler’s final directive to strike: Army Group North, eastward from Germany and south via East Prussia, and Army Group South northward through German-occupied Slovakia. The orders finally came through at 3 p.m.—the attack on Poland would commence at dawn on August 26, 1939.

The news of the Anglo-Polish treaty reached the Reich Chancellery later that afternoon, causing Hitler to falter. After a 7:30 p.m. meeting, the Fuhrer canceled the invasion of Poland. It would have to wait in light of the new British resolve.

As Hitler deliberated in Berlin, Herzner was briefing his commandos near the Slovakian-Polish border. Tough and smart, the young officer had earned his doctorate years before being hired on as a research assistant at the German Army High Command in 1938. Unbeknownst to his new employers, at the time he began his new career the young intellectual was already a member of a right-wing resistance group whose main goal was the assassination of the leader of the Nazi Party, Hitler himself. The main impetus for the secret plot was the fear that the Fuhrer would bring the German nation into a world conflict that, according to Herzner and his friends, the country was unprepared to wage.

In the end, Hitler’s political maneuvering and signing of the Munich Agreement in late September 1938 eliminated the perceived threat of imminent war. The pact with the Allies caused Herzner’s group, which lacked a clear plan of action, to disband. Thoughts of assassination long forgotten, Herzner found himself recruited by the Abwehr to lead one of its secret commando groups.

The Brandenburger units drew personnel from ethnic German minorities in Eastern and Central Europe. Not regular army men, they were highly trained, rugged, and dangerous individuals leading covert sabotage operations. With the orders to enter Poland on the eve of the general German invasion across three fronts, Canaris’s commandos, composed of many Polish-speaking irregulars, split the infiltration and disruption responsibilities between three units. Two were to smuggle in high explosives and sabotage vital military and communications targets directly across the Slovakian and Polish border. The third group, led by Herzner, had a more delicate and most important mission.

It was nearly midnight when Herzner’s commandos, dressed in civilian clothing with swastika armbands as the only indication of their allegiance, listened attentively to the last debrief. Wearing his full Wehrmacht uniform, he gave a single automatic weapon, a pistol, and four ammo magazines to each of the 24 men. Trucks were already waiting outside to take them to the Polish border. Once there, Herzner’s men would proceed on foot through the Beskids Mountains and toward the Jablunkov Pass. Their goal was to go hours ahead of the German invasion and, after regrouping, capture a railway station and a tunnel at the town of Mosty, three miles inside the Polish border. With the area secured, Herzner and his men would wait until dawn for the leading German units of the Army Group South.

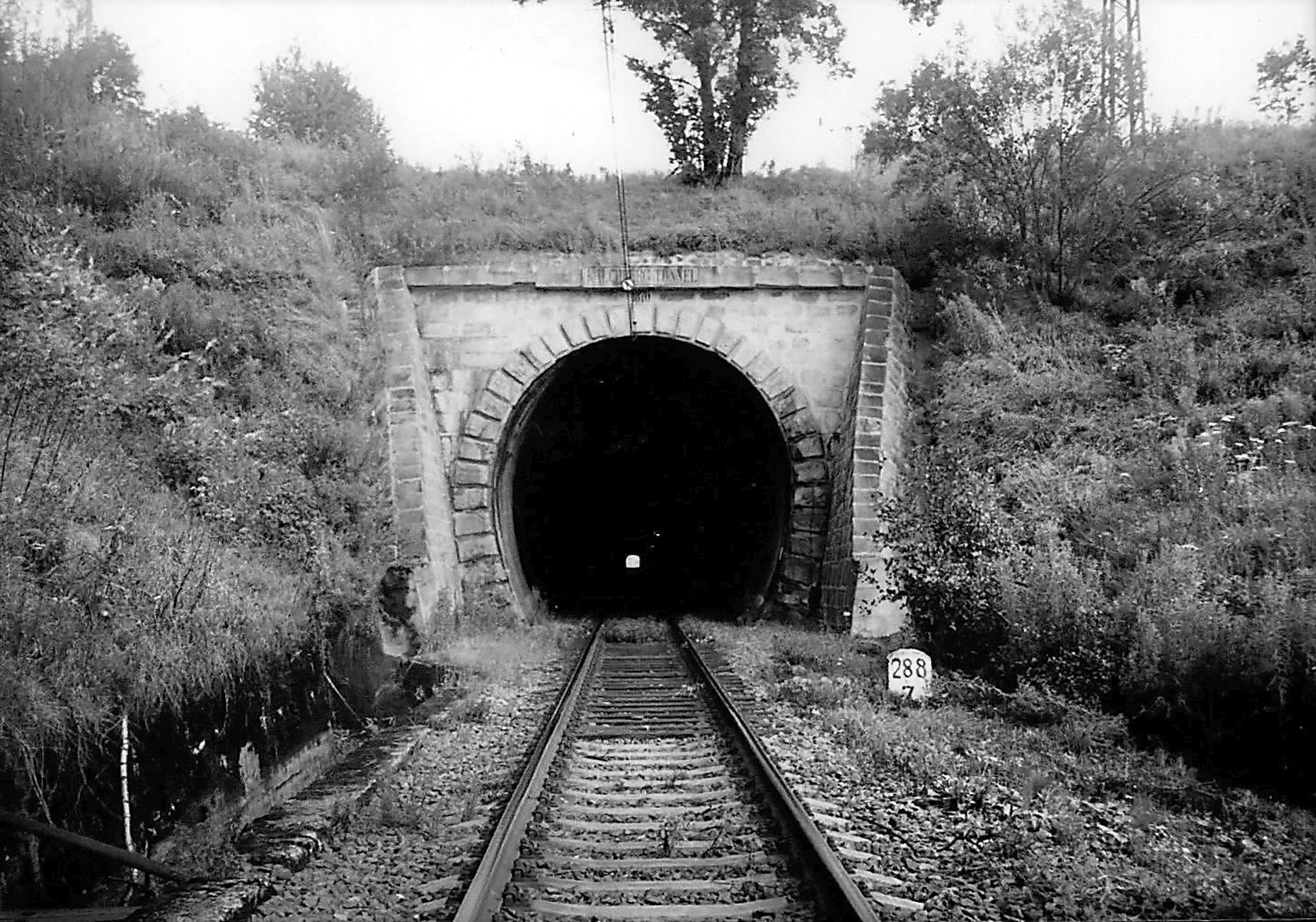

The Mosty station was the last on a rail line running through the nearby tunnel of Jablunkov Pass that linked German-occupied Czechoslovakia and Polish Silesia. Securing the station and the tunnel was imperative to the success of the Nazi invasion of Poland as it provided the shortest route for Hitler’s troops and supplies coming from Vienna toward Warsaw, the Polish capital city. It also opened up the defenses of Cracow, Poland’s ancient city and one-time capital, where Army Group South was expected to contain most of the Polish forces before driving north to Warsaw.

Herzner and his men emerged from the woods that formed a natural border between Poland and Slovakia shortly after midnight and began their secret trek up the mountains toward their target. Most were ethnic Germans born in Poland or individuals who, after the Treaty of Versailles, found themselves on the wrong side of the border. They needed little urging to strike at the Poles whom they saw as oppressors, a view strengthened by Nazi propaganda.

Herzner led one of the assault units as he and 12 men avoided Polish sentries. The latter’s numbers seemed to multiply the closer the Germans got to the Mosty station. As agreed during the mission debrief, his group was to meet the other team at 3 a.m. on a hill overlooking the station. And while Herzner and his commandos arrived 15 minutes ahead of schedule, the other unit was nowhere to be seen. Unknown to Hersner, they had lost their way inside the thick Polish forests only to be found by one of the Abwehr sentries and recalled to Slovakia.

Knowing the significance of the Jablunkov Pass, the Poles had mined the 1,000-foot-long tunnel months earlier, according to spies. The missing assault team was to approach the tunnel further down the rail line as Herzner’s detachment took care of the Mosty station. It now seemed likely that his unit would have to secure the first target without alerting the tunnel guards while hoping for the arrival of the second team before moving on to take the tunnel. The brightening sky made this the only choice.

At 4 a.m., Herzner and his commandos swept down the hill, firing their weapons. The element of surprise had been lost. Besides, Herzner believed that armored reconnaissance cars of the main invasion force would be there any minute to help secure the tunnel. He also believed other teams had sabotaged the area’s telecommunications buildings and telephone network.

The Polish border police, regular army troops, and railway workers put up a staunch defense but were no match for Herzner’s highly trained and well-armed commandos. The Germans promptly surrounded the station building and a few others nearby. White tablecloths soon fluttered from the structures’ windows. Speaking in Polish, one of Herzner’s men ordered whoever was in charge to officially surrender the building. A frightened middle-aged Polish colonel came through the door with his hands up. Herzner, the only man dressed in a German military uniform, lowered his pistol and approached the Pole. “What’s the matter? Aren’t Germany and Poland at war?” As one of the commandos translated, the Pole replied, “No, they aren’t. You can find out for yourself.”

“Wie?” (How) Herzner asked, undoubtedly already suspecting the worst.

“By calling your base on our telephone,” the Polish colonel replied.

The German lieutenant did not need the translation and he now knew his situation was worse than he already thought. Minutes later, the young Polish woman sitting at the desk with the military communication equipment in the rail station’s basement bowed to the tall German officer as he entered. There could not have been any doubt in Herzner’s mind that she had already done her duty and notified the tunnel security of the attack on the station. At that very moment, one mile down the road sappers were finishing arming the explosives while the Polish border patrol set up machine-gun posts at each end of the tunnel.

Herzner was initially reluctant to break any radio silence. Yet, an almost immediate attack by the advanced Polish guard units from Jablunkov Pass, who came to assess the damage at Mosty station, convinced the lieutenant to do otherwise. At nearly 5 a.m. and after repelling the Poles’ advances, Herzner had the Polish woman make the phone call. Still, to his aggravation, the operator from the closest telecommunications building refused to patch the call through. Now desperate for information and worrying about why the Army Group South units were nowhere to be seen, the German officer ordered one of his men to confiscate a locomotive and take it back across the Slovakian border toward division headquarters.

The frightened Polish woman promptly handed the telephone to the German officer when it rang. Herzner had been pacing back and forth inside the small windowless basement and now rushed to grab it from her. The divisional intelligence officer screamed through the receiver. The lost assault team had been found and recalled; there was no attack on Poland on this day. The Fuhrer had canceled it. “Retreat at once! Release your prisoners, vacate the station building, and return by the quickest route.”

Herzner rounded up his men, telling them reinforcements were not coming. The group might have carried out its mission, but there was now nothing left to do but disappear into the mountains. With an armed Polish detachment close behind, the commandos finally snuck back across the Slovakian border early in the afternoon. At Polish headquarters, there was no longer any doubt of Hitler’s plans for Poland in 1939.

Following the August 26 incident, the Poles secretly stepped up their mobilization campaign. By the time of Hitler’s attack five days later, they had activated three-quarters of the Polish armed forces. Meanwhile, the German government did not acknowledge the incident, and the Poles, under a gag order from the British and French, chose not to pursue any official countermeasures.

German General Eugen Ott, the commander of the 7th Infantry Division stationed across the border from Mosty, sent an official apology to his counterpart in the region, Polish Gen. Josef Kustron of the 21st Mountain Infantry Division. Ott claimed a crazed individual acting on his own was responsible for the Jablunkov Incident. It was a veiled excuse and the Poles knew it was only a matter of days before the Germans invaded.

The situation on September 1, 1939, would be much different. Having wavered in his resolve for a few days after the announcement of the British pact with Poland, at 12:40 p.m. on August 31, Hitler reinstated his order to invade Poland. “Since the situation on Germany’s eastern frontier has become intolerable, and all political possibilities of the peaceful settlement have been exhausted, I have decided upon a solution by force,” the Fuhrer would explain. Hitler began his war with another covert operation, this one a bit more known to history. Mere days before Herzner’s invasion, the German leader told his military commanders, “I will give a propagandistic cause for the release of war, whether convincing or not. The winner is not asked later whether he said the truth or not.”

In line with the Jablunkov Pass and Mosty mission of August 25-26, the new operation was launched less than a week later. This time a small commando unit would give Hitler his cause for war with a mock attack on a German radio station in Gleiwitz by SS units dressed as Polish insurgents. Leaving behind a planted dead body of a Pole as proof of the Polish presence and deception, the commandos broadcast a message in Polish. “Attention! Here is Gleiwitz! The radio station is in Polish hands!”

When the Germans finally crossed the Polish borders in the early hours of September 1, 1939, Herzner was still debriefing from his successful, albeit failed, mission. He was nominated for an Iron Cross, but rejected because his August 25 skirmish took place before the war began. Ironically, what his men accomplished, the main invasion failed to repeat—the Poles detonated explosives blocking the Jablunkov Pass less than an hour after the September 1 hostilities began.

Following his actions in the fall of 1939, the Abwehr promoted Herzner to lead the “Nightingale Battalion,” a pro-German volunteer Ukrainian unit tasked with sabotage and diversion, first against Poland and later the Soviet Union. His clandestine actions finally won him the Iron Cross shortly before being severely wounded on the Eastern Front in late 1941. After months of rehabilitation in a German sanatorium, the avid swimmer was found drowned in one of the complex’s pools on September 3, 1942. His death, like his otherwise obscure life, were all but lost to history like his untimely invasion of Poland in the late summer of 1939.

Very interesting. As much as I’ve read about WWII over my lifetime, and it’s a lot, I’d never heard of this incident until today.