By Peter Zablocki

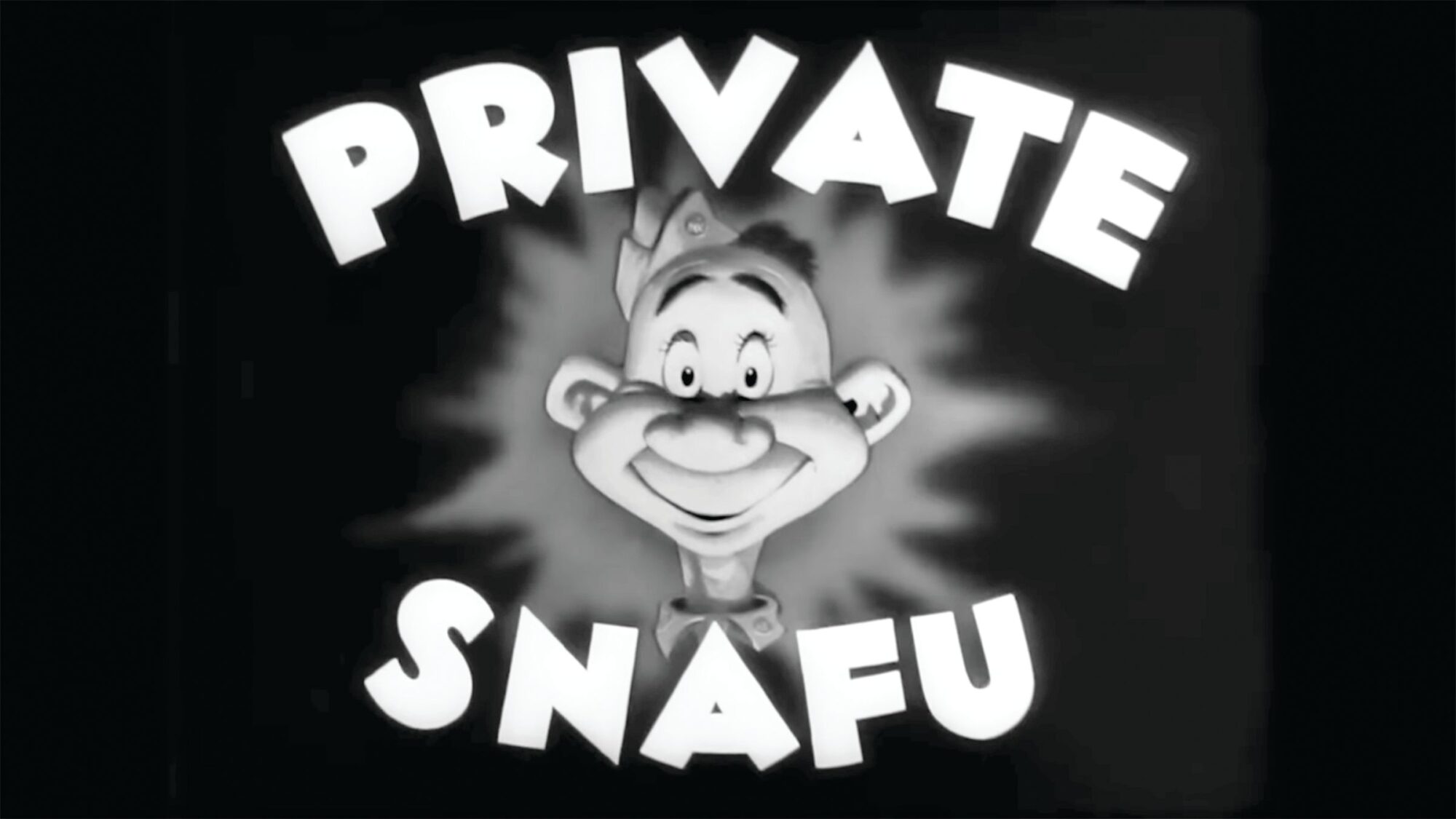

Bumbling Army Private Snafu was the title character of a series of 26 short cartoons sanctioned by the U.S. War Department, produced by Frank Capra, and written by Theodor “Dr. Seuss” Geisel between 1943 and 1945. Instructional, ironic and humorous, these animated shorts set out to teach new soldiers about security, sanitation habits, and the pitfalls of general stupidity and misconduct. More than anything, Private Snafu was able to unite the troops in coping with the emotional distress of fighting in the greatest conflict the world has ever seen.

Thousands of patriotic young Americans jammed military recruiting offices the day after Pearl Harbor. Though impressive, the five million volunteers would not be enough for the challenge of fighting a two-front war in Europe and the Pacific. Anticipating entrance into the conflict, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the U.S. Congress had passed the Selective Service Act of 1940. Activating the first peacetime draft in American history added 10 million soldiers between 18 and 45 to those volunteers.

Now the federal government had to plan the best way to house them, train them, and make them battle-ready. The first was easy, but the latter proved an obstacle. There was much more to basic training than teaching a citizen-soldier how to stand at attention, march for miles on end, handle a rifle, or follow orders. What was needed was an all-in attitude, dedication, grit, and compliance.

Courtesy of Capra and Geisel, the Army introduced American GIs to the tongue-in-cheek Private Snafu (an acronym for “Situation Normal, All—Fouled Up”), a short, bald, motor-mouthed example of what a soldier should not be. The depiction of Snafu catching tropical diseases, leaking classified information, and dying from general negligence, taught the troops the downside of being naïve, careless, and continuously amorous.

Most importantly, the soldiers picked up their essential subtext—that compliance, brotherhood, empathy, and sometimes plain common sense meant survival.

The series was initially designed to educate young soldiers with limited education in military topics and improve their morale after being taken away from their homes and everyday lives. According to the National World War II Museum, the low level of education of many enlisted men was one of the biggest hurdles in assimilating them into the armed forces.

Seventy percent of all men accepted into military service had dropped out of school, with 500,000 having less than a fourth-grade education, and 4.4 million having less than an eighth-grade education. College graduates made up less than five percent of the Army’s ranks, with some estimates showing the mental age of the average soldier to be between 13 and 14 years old.

Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Army assigned Brig. Gen. Frederick H. Osborn, a social science researcher before the war, to spearhead the Army’s Information and Education Division. While its most known propaganda project—Capra’s “Why We Fight” series—was a perfect overview of the seriousness of war, it was not until the Private Snafu shorts that the unit reached its first real success in educating new recruits.

Before the first episode of Private Snafu was shown in 1943, the Army instructed its troops on security, proper sanitation, and other military subjects essential to proper soldiering via 11 pre-planned lectures in large group settings. Converting hundreds of thousands of civilians with minimal education into military specialists seemed nearly impossible.

Together with Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall, Osborn had an idea of combining indoctrination with instruction into a single effort. Warner Bros. Studios, with its already blatantly anti-Nazi sentiment present in their feature films, seemed a logical choice.

The studio’s Daffy Duck and Bugs Bunny cartoons, shown before feature films, were a massive hit. And, although after 1941, the cartoons often carried strong pro-war and anti-fascist messages meant to arouse public involvement, they managed to stay entertaining, lighthearted, and relatable. The Army saw that a similar format would be the perfect way to reach a newly conscripted audience of varying educational backgrounds.

To create their own indoctrination and social engineering experiment preparing soldiers for what lay ahead, the U.S. Army Signal Corps turned to the famed animated studio Warner Bros.—home of Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies, featuring Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, and Porky Pig, all voiced by the iconic Mel Blanc. The Snafu shorts were directed by American animation legends Charles “Chuck” Jones (12), Isadore “Friz” Freleng (8), Frank Tashlin (4), and Bob Clampett (2).

Not taking any chances, the Army placed Capra, an award-winning movie maker responsible for such Hollywood classics as Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) and, after the war, It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), at the helm of the project.

After the Italian-born Capra came up with the name “Private Snafu,” the team went to work creating a character known for committing blunders and infractions, then learning from the consequences of his mistakes—or dying as a result. Considered “for-military-use-only” and even classified at the time of their creation, each episode served a double purpose of having a plot about specific instructional material at its core while sneakily inserting underlying indoctrination messages.

The silly stories had the desired effect of teaching soldiers the facts of military life. In the episode titled “Fighting Tools,” Snafu neglected the upkeep and maintenance of his advanced weaponry, which led to his death at the hands of a German soldier. And in “Gas,” Snafu is saved from the vicious gas monster only after he finally embraces his gas mask training with the mask having female facial features and being cuddled and cared for by the idiotic private.

In “Booby Traps,” Snafu learned of dangers other than gunfire and staying vigilant at all times in the field. Even after his negligence sent him to heaven, he’s plagued by booby traps.

There was also the issue of personal hygiene, best exemplified in “Private Snafu vs. Malaria Mike,” which saw a malaria-armed mosquito kill the foolish private after he carelessly ignored military instruction.

Ironically, most of the instructional cartoons had more to do with the right attitude and the less obvious but ever-present subversion. While “Hot Spot” stressed the importance of a proper diet on a given march, “The Chow Hound”story centered on not wasting food.

The plots of “Three Brothers” and “Infantry Blues” focused on rumors that other service branches were safer or more glamorous. In the former, Snafu wishes he had the easier posts of his two brothers—a carrier pigeon caretaker and a K-9 dog-unit trainer—only to realize that their jobs required as much dedication and alertness as his own.

In the latter episode, a tired Snafu marches through rugged terrain, fantasizing about how much better, simpler, and safer the other military branches had it.

A Technical Fairy, First Class—a side character that plays the part of a “sergeant godfairy” granting Snafu’s wishes—shows up and allows the private to experience the unpleasant aspects of being a sailor, a pilot, and a tankman. The episode ends with Snafu back slogging through his march in the desert but now much happier and more content with his situation.

One constant message that often appeared throughout the series was that spies were everywhere and nobody was to be trusted. “Loose lips sink ships” was especially the motto in “Spies,” “Rumors,” “Snafuperman,” and “Going Home.”

In “Spies,” Snafu blabs about his everyday military life to everyone he meets and they pass it on to the enemy. As a result of his actions, a German submarine sinks the very transport ship Snafu is on, killing him and all others on board.

In “Rumors,” the focus is on the damage of disreputable gossip when the bumbling Snafu took someone’s suggestion of the skies being perfect for a bombing and turned it into a morale-hurting rumor that deterred the entire camp and saw the private locked up in an insane asylum.

In “Snafuperman,” the private, graced with superpowers by the Technical Fairy, brags about his powers and advantages only to have the enemy use his boasting to plan a more precise bombing of American military targets. The message was simple—information, when misused or used without caution, was detrimental to the war effort.

While cringe-worthy by today’s standards, the prejudiced depiction of Snafu’s enemies was exactly what the soldiers at the time wanted to see. Although humorous, the cartoons made it very obvious that the Germans and Japanese were formidable foes and should be treated as such. The characters were often physically larger than Snafu and very determined to use that advantage to kill him.

The enemy was also dangerous because of his cunningness and bullying, not so much because of his strength. The writers and artists managed to ridicule and belittle the Axis powers while simultaneously making them appear just dangerous enough.

The animated shorts depicted the Japanese with racial stereotypes: slanted eyes, buck teeth, deformed heads, and large ears. They had no natural intelligence but used deviousness and scheming—and Snafu’s blundering—to gain an advantage. Similarly, the Germans were often big brutes and buffoons quick to surrender to American military superiority.

“Oh, no—what a rifle!” screamed a huge German soldier who cowers after facing the GI’s weapon. The young men whom the Army was sending into battle might have been intimidated by the Japanese and German forces—but Snafu cleverly eased some of those fears by presenting their foes as weak and morally inferior.

Although packed with much information, Snafu’s stories still managed to include the same type of slapstick humor that made their Warner Bros. cousins back home so popular.

Forever careless, the young private never did anything right and always had to pay the ultimate price for his stupidity. He was the worst soldier in the Army, to whom the young men watching never wanted to be compared.

The public ridicule that resulted from Snafu’s blunders served a perfect double purpose—it made the soldiers laugh while cautioning them against suffering the same fate.

Yet, the writers were always aware of the seriousness of their project and the impact it would have on the lonely young men thousands of miles from civilian normalcy.

The possibility of death was always present for Snafu. After all, non-compliance and stupidity got him killed in six out of the first thirteen episodes, with the remaining adventures having him end up in a German prison, a military jail, and the psych ward.

Unlike Daffy or Bugs, when Snafu died, he was dead for that episode. Although humorous, the cartoons had to be sensitive to the real fears that came with military life—they had to be educational, funny, and most importantly, authentic to the troops in the audience.

What endeared Snafu to the young soldiers was that, like them, the lonesome private was always overworked, uncomfortable, dirty, bored, exhausted, and all-too-close to danger. Accepting Snafu’s fate when he did what he should not have, allowed the American GIs to see all the training and hardships they had to endure as essential to their survival. Together with Snafu, they learned that maintaining discipline and doing their duties, while seemingly trivial at the time, enabled the military to run accordingly, keeping them safe.

Private Snafu finished with the end of the Second World War. It had completed its intended mission of instructing less-educated young men in proper military safety and procedures. Yet it managed to do so much more. It allowed a citizen army to see the larger picture of why they were fighting and what needed to be done for that fighting to stop so they could all go home.

Weary of war, they were ready to go back to civilian life and rejoin their other favorite cartoon characters that stayed behind—Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, and Porky Pig. To the men, Snafu was left behind along with their uniforms, rifles, and gear—a much-needed tool of war, no longer necessary in the time of peace.

Peter Zablocki is a historian, author, and educator living in Denville, New Jersey. Visit www.peterzablocki.com.

The article comments on the Japanese appearance as racial bias but SNAFU was not an accurate depiction of an American soldier. The cartoons of that time depicted everyone different than a real person would look. I do not think Freddy Fud looked normal so give me a break with the PC stuff.