By Major Dominic J. Caraccilo

On July 12, 1845, Sir John Franklin, an aging outcast in the Royal Navy, was last seen sailing with his crew from Greenland into Baffin Bay in an attempt to find the coveted Northwest Passage. For this mission, the British Admiralty had assembled the largest expedition yet; refitting two ships with steam engines and placing the seasoned if somewhat lackluster Franklin in com- mand of the 128-man expedition.

Franklin’s lavishly outfitted expedition is one of the most enduring mysteries in the annals of exploration. For years historians have pondered why the most technologically advanced Arctic expedition of the 19th century, capable of defining a navigable shortcut over the top of the world and linking the rich markets of the East and West, became, according to author Scott Cookman, “the greatest Arctic tragedy of the age.” There had been eight previous military polar expeditions since 1819 and only 17 deaths out of 513 men. The loss of Franklin’s entire crew was one of the greatest British naval disasters.

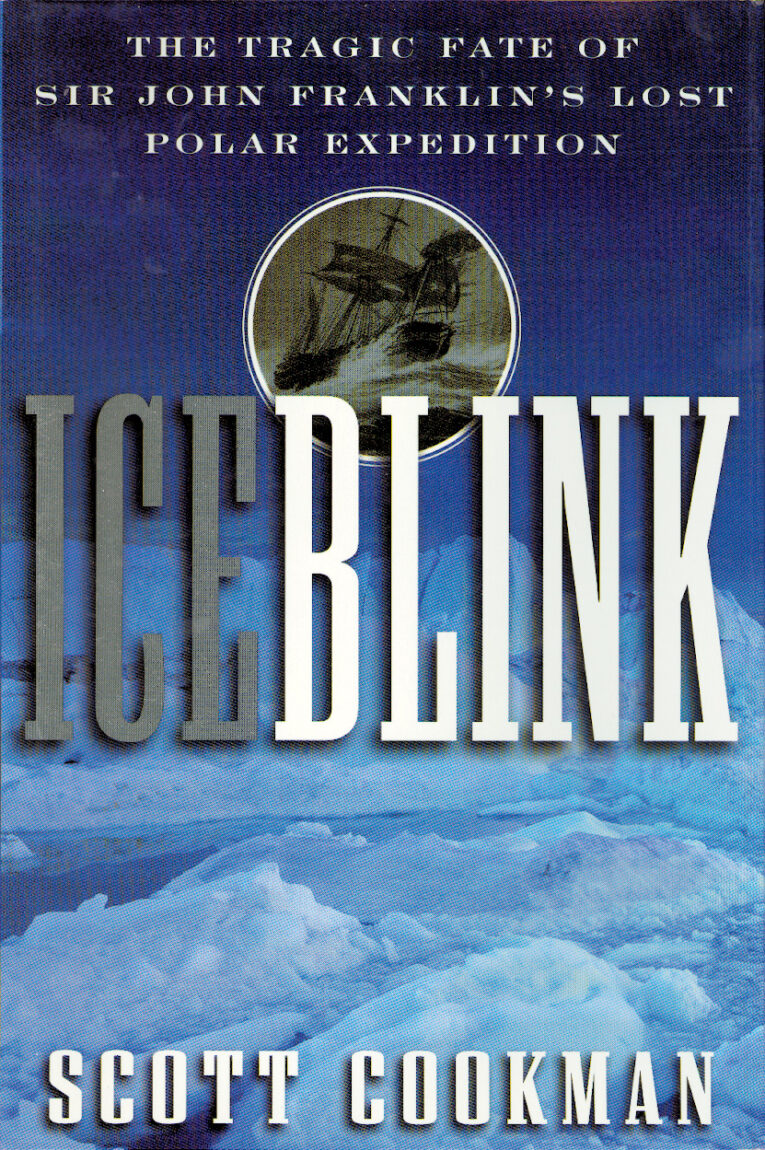

Ice Blink: The Tragic Fate of Sir John Franklin’s Lost Polar Expedition (by Scott Cookman, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 2000, 244 pages, photographs, illustrations, maps, appendices, bibliography and index; $24.95, hardcover) masterfully examines the individual errors and remarkable twists of fate that led to the demise of the crews aboard the HMS Terror and HMS Erebus. While it was perceived that the survival of the expedition hinged wholly upon what it took into the Arctic, the irony was that this viewpoint led to its demise. Tainted food supplies coupled with an ambitious crew size is Cookman’s horrifying explanation for what went wrong.

Ice Blink: The Tragic Fate of Sir John Franklin’s Lost Polar Expedition (by Scott Cookman, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 2000, 244 pages, photographs, illustrations, maps, appendices, bibliography and index; $24.95, hardcover) masterfully examines the individual errors and remarkable twists of fate that led to the demise of the crews aboard the HMS Terror and HMS Erebus. While it was perceived that the survival of the expedition hinged wholly upon what it took into the Arctic, the irony was that this viewpoint led to its demise. Tainted food supplies coupled with an ambitious crew size is Cookman’s horrifying explanation for what went wrong.

Ice Blink is about mismanagement, oversights, government foibles, prejudice and incompetence. In fact, an oversight by the Admiralty caused the ultimate doom of the expedition because it relied on untested technology such as the steam engine, armor plating and canned provisions. Cookman uncovers the “grotesque handiwork” of an “evil man,” Stephan Goldner, who infected the expedition with poisoning and botulism. The lowest bidding manufacturer, Goldner’s Canned Food, was the exclusive supplier of provisions for the expedition. No one in the navy bothered to check the filthy conditions at the Goldner factory. Shortcuts in manufacturing of the cans led to an infestation of a toxin so deadly that in the end the entire crew succumbed.

Ice Blink (the name sailors give the haunting mirages formed by reflections of pack ice) draws on early accounts from relief expeditions as well as recent archeological evidence. Some nine years after the voyage, search teams located numerous indications of the crew that went ashore after the ships became “beset in a maelstrom of ice in the heart of the Arctic archipelago” in September 1846. The only thing Sir Franklin left behind were two faded ship muster books, a six-foot-tall chinked stone cairn surrounded by the crew’s belongings and, probably most defining, a small, sail-rigged boat that included two skeletons.

From these sullen items, historians eventually pieced together a story of desperate survival that eventually led to cannibalism, and quite possibly, murder. Despite all of this despair, Ice Blink is also about the bravery, loyalty and the resourcefulness of the men who served on the expedition. By all accounts, they did everything they could to survive and to help each other during the difficulties that such a voyage entails.

Ice Blink is an exceptionally well written and smartly compartmentalized book. It is the type of adventure reading that instantly gains a reader’s interest. Drawing on parallels with the recent Apollo space program, Cookman expertly conveys the importance of finding the Northwest Passage. Although no one actually completed a passage until 1906, some 60 years after Franklin’s attempt, the 1845 expedition taught some enduring lessons about excursions into the unknown. In the end, Scott Cookman’s first nonfiction narrative is at once a medical thriller and well-researched chronicle of 19th century naval history.

The Nazi’s March to Chaos: The Hitler Era Through the Lenses of Chaos-Complexity Theory, by Roger Beaumont, Praeger Publishers (Greenwood), Westport, CT, 2000, 214 pages, illustrations, notes, bibliography, and index; $59.95, hardcover.

By the author’s own admission, “this study is not a technical treatise on non-linearity, but an examination of the Hitlerzeit [Hitler era] from the perspective of chaos-complexity.”

The basic premise of The Nazi’s March to Chaos is one of exploration. Specifically Beaumont, using chaos-complexity theory, questions if there are new and useful perspectives on how events unfold. The Hitler era and the actions leading to World War II are the author’s vehicle by which this experiment is conducted. In fact, if his premise is correct, his theoretical findings and concepts can be used for exploring any historical “systems.”

The Nazi’s March to Chaos explores the Third Reich as a chaotic system and the intricate causal roots of the Endloesung, or Final Solution. Topics discussed include the clash between the image of Nazi technical prowess and the antimodernism in National Socialist ideology, the Nazi propaganda machine employment of a façade of order over the inner base of chaos, and German and Nazi military tactics and doctrine as ways of coping with the chaos of war and imposing it upon the enemy. Beaumont also looks at attempts to instill the arrogance and rage of the Nazi Party’s brown-shirted stormtroops into the Wehrmacht through the National Socialist Leadership Officer program, the “Nazi Commissars.” In the end, Beaumont, Professor of History at Texas A&M University, provides sufficient analysis to answer the basic question of his thesis: “How much does looking at history through the lens of chaos-complexity theory offer new and useful perspectives on how history is crafted by historians and how it actually works?” The answer one draws from this seminal work, that amalgamates science with history, is a thought-provoking and unique way of exploring the contradictions that make up the “tachycardia of horrors” like the Hitlerzeit.

Recent and Recommended

Civil War Eyewitnesses: An Annotated Bibliography of Books and Articles, 1986-1996, by Garold L. Cole, University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, SC, 2000, 271 pages, index; $39.95, hardcover.

More than 80,000 titles studying the American Civil War exist, an average of “more than one book or article per day since [the] civil war began almost fourteen decades ago,” writes Garold Cole in this work.

In a sequel to the 1988 award-winning first volume that recounts an annotated bibliography of Civil War books and articles printed in the years 1955-1986, Cole continues his mastery of the bibliographical reference world. Civil War Eyewitness catalogs 596 firsthand accounts of the Civil War that appeared in print in the subsequent decade from the last volume, an increase of almost two-fold from his seminal work.

While bibliographies, by nature, are not exciting to read, Civil War Eyewitness is the exception. Cole’s annotations stand alone as quick, informative synopses of individual accounts. Readers of Civil War Eyewitness will find the personal narratives both appealing and scholarly. They showcase in a snapshot the totality of America’s experience with civil war.

Divided into neatly arranged sections to include “The North,” “The South” and “Anthologies, Studies, and Foreign Travelers,” each annotation includes many important facets of the work. Indicated in each is the period the document was written, the type of document, individual ranks, units involved, descriptions of the engagements and other topics of interest associated with the article or book.

As Dr. James I. Robertson, Jr. has suggested in the Foreword, precious few bibliographical guides have appeared to offer stable ground for research. Civil War Eyewitness is the anomaly. It is more than just a catalog; it is an informative book arrayed to offer a plethora of information in a concise, readable form.

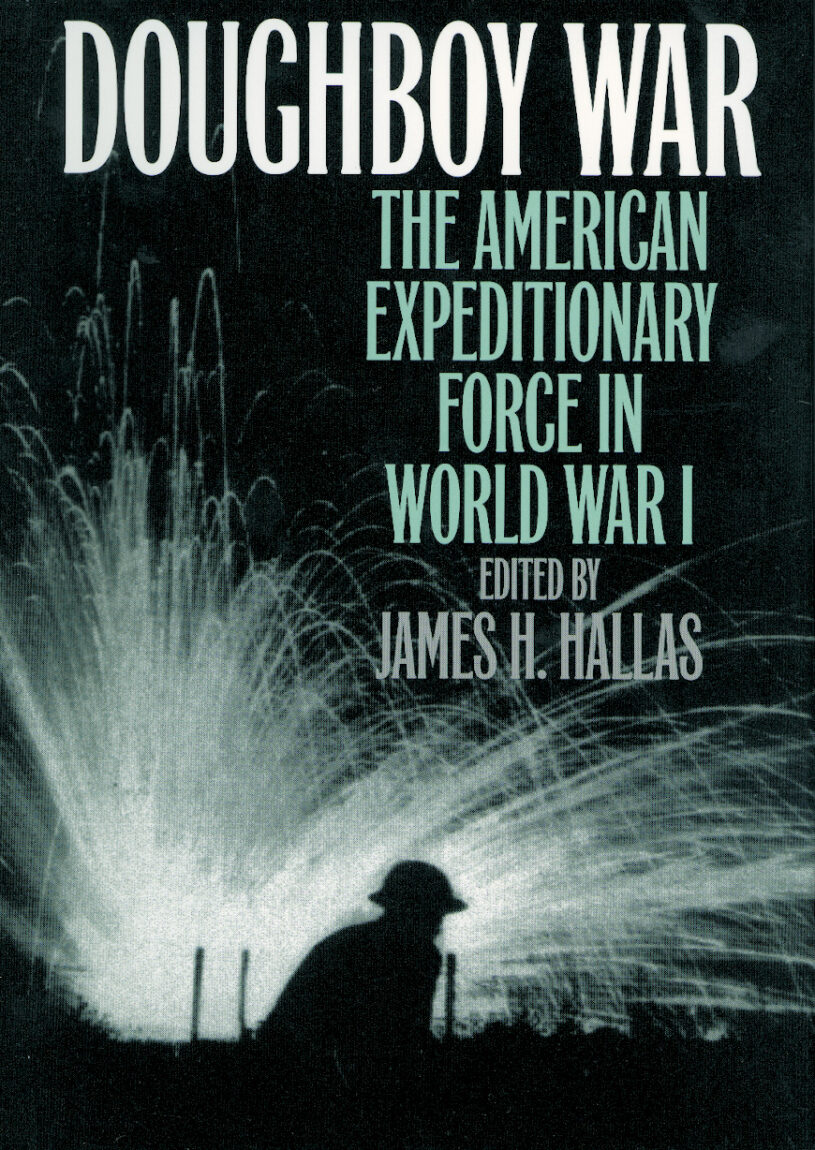

Doughboy War: The American Expeditionary Force in World War I, by James H. Hallas, Norton, New York, 1999, 298 pages photographs, bibliography, notes, $14.95, softcover.

Doughboy War: The American Expeditionary Force in World War I, by James H. Hallas, Norton, New York, 1999, 298 pages photographs, bibliography, notes, $14.95, softcover.

The “jaunty young men with quaint dishpan helmets” are gone and largely forgotten. But James H. Hallas, esteemed author of the likes of The Devil’s Anvil, offers a multilayered history of World War I’s doughboys. Gaining personal narratives, unit histories, diaries and journals from myriad sources, Hallas relates an incredible anthology of stories about men in combat. Compiling a first-person menagerie among the nearly five million Americans who served in the Armed Forces during WWI, Doughboy War captures the full flavor of the American Expeditionary Force.

The flood of American manpower arriving in France in 1918 “erased any hope Germany had for outright victory.” Surprisingly the majority of America was eager to get to France and, above all, to reach the front. “Perhaps,” as one of Hallas’s contributors stated, “we were offended by the arrogance of the German U-boat campaign and convinced that Kaiserism must be smashed, once and for all.” Doughboy War conveys this eagerness and innocence as each individual narrator portrays an unwavering enthusiasm for enlisting and contributing to the war in any way he or she could.

Doughboy War takes flight from this eagerness into a hover of anxiety as the contributors cross the Atlantic. The reader is privy to a full array of accounts of intriguing stories of travel as the doughboys reach their destination just short of the front. Then, each account of battle reveals the horrible nature of war.

From the first experiences in the muddy trenches to the bloody battle for Bellau Wood, to the violent clash on the Marne and the seemingly unending morass of the Argonne, Doughboy War is at once a tribute to the heroes of a great war and resounding evidence that war, indeed, is hell.

Order of Battle: Allied Ground Forces of Operation Desert Storm, by Thomas D. Dinackus, Hellgate Press, Central Point, OR, 2000, 175 pages, maps, photographs, tables, appendices, bibliography, index, $17.95, softcover.

An amazing amount of research not previously available is contained in Thomas D. Dinackus’ Order of Battle. Not a typical reference book, this is an intriguing study and subsequent listing of all the U.S. Army, Marine Corps, French and Arab/Islamic units that served in the Gulf War. It depicts the unique command structure between units before and during the battle.

Order of Battle is smartly apportioned to include an Introduction that depicts the purpose and methodology of the “project” and a definitive description of how the book should be used. A composite listing of abbreviations and a beautifully organized series of maps in the Prelude makes Order of Battle an all-inclusive reference source for the Persian Gulf War.

But the incorporation of a short chronology coupled with a description of forces partitioned by battle operating systems make this book more than just a reference. It is undoubtedly the best single-source resource-enriched chronicle of Operations Desert Shield, Desert Storm and the restoration campaign that ensued.

The work also identifies the major types of equipment used by each unit, and other substantial information, such as identifying the Apache attack helicopter that fired the first shots of Desert Storm and the first Patriot missile to engage an Iraqi Scud. It compares the Army and Marine Corps forces deployed to the Gulf and compares Desert Storm to Vietnam and Korea.

Anyone interested in military history or war games, as well as those stationed in the Gulf during Operation Desert Storm, will be interested in this thoroughly researched book. Order of Battle is an essential reference for military buffs, insignia collectors, and students of ground combat in modern warfare.

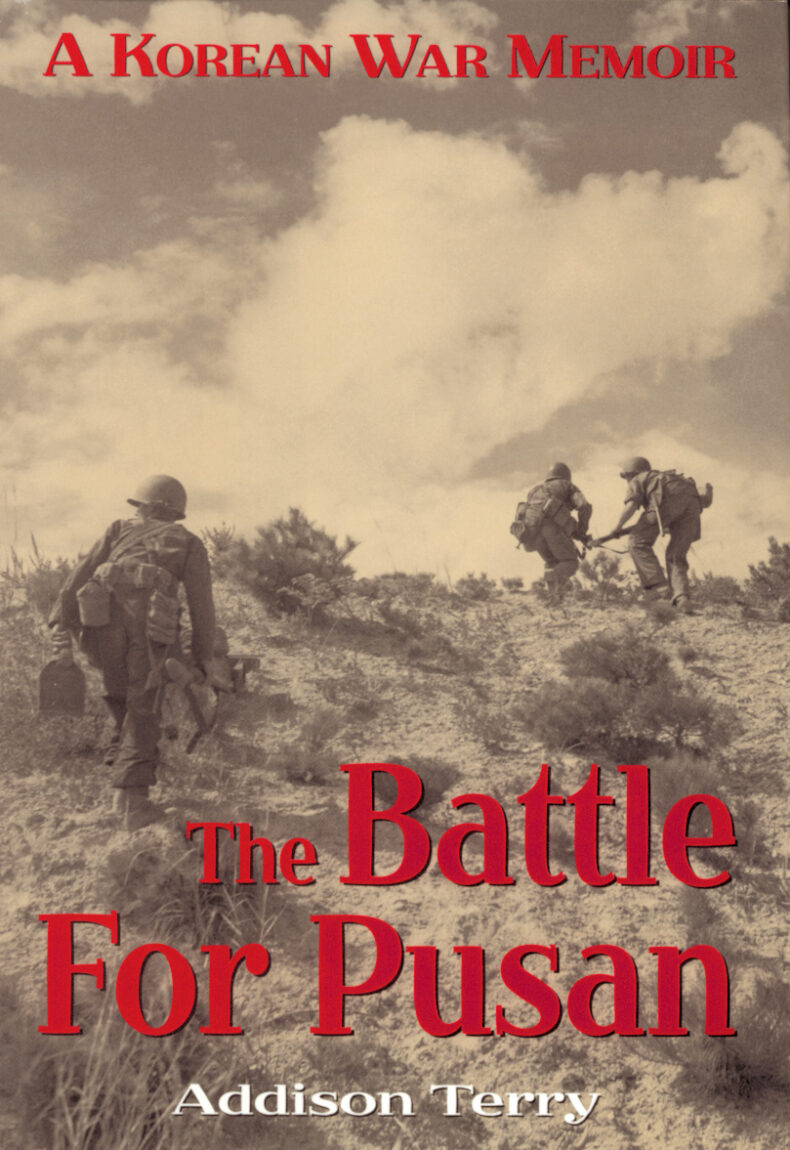

The Battle for Pusan: A Korean War Memoir, by Addison Terry, Presidio, San Marin, CA, 2000, 233 pages, maps, glossary, photographs, $27.95, hardcover.

The Battle for Pusan: A Korean War Memoir, by Addison Terry, Presidio, San Marin, CA, 2000, 233 pages, maps, glossary, photographs, $27.95, hardcover.

The Battle for Pusan was written in the winter of 1950-51 from a hospital ward in Fort Benning, Ga., while “the wounds still hurt and the young memory [was] still fresh.” Accordingly this is not just another “I was there” type recollection pieced together after 50 years of reminiscence. The Pusan Perimeter was held for 82 days, but until September 15, 1950, the day of MacArthur’s daring amphibious landing at Inchon, there was doubt about whether the American and Republic of Korean (ROK) forces could hold out.

In July of that same year, the main line of resistance from Yongdok on the east coast, to Andong, to Sangju, to Taejon and on to Kunsan on the west was in jeopardy. The perimeter was not established until the first day of August, encompassing a pocket running 85 miles north to south and nearly 60 miles east and west.

The Battle for Pusan is an accurate and engaging account of the 27th Regiment of the 25th Infantry Division and the 8th Field Artillery Battalion in the first days of the war as experienced by a 22-year old green lieutenant. It rushes readers “from hill to hill” revealing, at once, the commonality of battle and the overwhelming confusion and fear that war in the early 1950s exhibited.

Then-Lieutenant Addison Terry was entrusted with lives and missions far beyond his training. His well-written recollections document his unit’s desperate struggle to maintain the perimeter and escape an American Dunkirk. Without enough troops to defend the Pusan perimeter properly, the 27th Regimental Combat Team was used as a “fire brigade,” rushing to shore up the imperiled American defenders and “staunch the threatened breakthroughs.”

Replete with stories of friendship, professional relationships and un-timely deaths, The Battle for Pusan is a first-rate memoir. Expect to be enthralled.

In Brief

American Military Leaders: From Colonial Times to the Present, Volumes I & II, by John C. Fredricksen, ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara, CA, 1999, 926 pages, photographs, notes, bibliography, and index; $175.00, hardcover.

These are quite possibly the most aesthetically-pleasing set of reference books on the market today. American Military Leaders: From Colonial Times to the Present profiles 422 men and women in an attempt to compile a suitable text for the general lay reader. It conveys concise information in a stand-alone uniform fashion.

John C. Fredrickson has amassed an appropriate body of leaders from the standpoint of both talent and accomplishment. He has meticulously chosen the volumes’ entries from a cross-reference of leaders who were prominent in their tenure. Not each was a hero in the conventional sense, but nonetheless each made a significant contribution to the nation. Junior officers, pilots, frigate captains, rebels, commandos, journalists, heroes and scoundrels “alike grace these pages for the enlightenment of all.”

Napoleon’s Elite Cavalry: Cavalry of the Imperial Guard, 1804-1815: The Paintings of Lucien Rousselot, text by Edward Ryan, Greenhill Books (Stackpole), London, UK, 1999, 208 pages, illustrations, appendices, index, $100.00 oversized hardcover.

A lavish, large format study of Napoleon’s guard cavalry, Napoleon Elite Cavalry: Cavalry of the Imperial Guard, 1804-1815, The Paintings of Lucien Rousselot is a stunning collection of full-color plates capturing the spirit of Napoleon’s finest. Ninety-one color plates illustrate the cavalry on campaign and on parade, with supporting text detailing the men and uniforms of the prestigious horse formations.

Full-page color prints display the late Lucien Rousselot’s paintings. The original plates, housed in the Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, illustrate Napoleon’s key units, including the Dragoons, Chasseurs, Polish Light Horse and Grenadiers.

This beautiful new book brings together, for the very first time, the work of one of the most recognized authorities on French army uniforms. Integrated with Edward Ryan’s finely researched and superbly written text, Napoleon’s Elite Cavalry is a valuable and unique collector’s piece.

In My Father’s Generation, by James Martin Rhodes, iUniverse.com, New York, 1999, 379 pages, $21.95, softcover.

James Martin Rhodes’ In My Father’s Generation is an amazing work of historical fiction that reads like a Jeff Shaara story. It is a tale of the American South in the post-Civil War era as seen through the eyes of John Warren, Corey Stokes and their families, one white and one black, but each playing a significant part in building the Southern timber industry.

Complex and well written, the story begins at the end of the Civil War, in the heart of Georgia during Sherman’s march-to-the-sea. It defines the struggle the United States endured to rebuild and reinvent itself in the years between the Civil War and World War I.

In My Father’s Generation is an extremely important book. It tells of the loves and losses Southern families shared and the fighting spirit that empowered them to prevail in life. At once a historically significant chronicle and a coming-of-age story, Rhodes’ first book makes one hope there will be a second.

Bullies and Cowards: The West Point Hazing Scandal, 1898-1901, by Philip W. Leon, Greenwood Press, Westport, CT, 2000, 193 pages, photographs, notes, glossary, bibliography, and index; $55.00, hardcover.

Philip W. Leon offers an exhaustively researched story about a century-old incident at the United States Military Academy at West Point. Bullies and Cowards: The West Point Hazing Scandal, is a synopsis of the scandalous affair that nearly brought down the hallowed walls of the infamous military institute. In this volume, Leon brings the reader painstakingly through the entire story, including the resultant investigations, testimonies and enduring conclusions.

“The fellows here are brutes, and they have evil minds,” writes the meek-mannered Oscar L. Booz to his parents in describing an underlying malicious intent to force him from the Academy. After four months of constant torment that included a beating in an organized, yet illegal, boxing match and a forced consumption of hot sauce, Booz gladly resigned. Eighteen months later, Booz died of tuberculosis of the larynx, a fate Booz’s family blamed on the Academy.

After Booz’s death congressional investigations ensued, revealing a long-standing cruelty that “had become inextricably identified with the Academy.” Both the Senate and House of Representatives considered closing the Academy, but military officials ensured Congress that they had “established control of hazing.” Leon’s Bullies and Cowards provides a unique look into a cadet’s life at the end of the 19th century with insightful comparisons to that of the present day.

A War to Be Won: Fighting the Second World War, 1937-1945, by Williamson Murray and Allan R. Millett, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2000, 640 pages, photographs, maps, appendices, bibliography, notes, index, $35.00, hardcover.

Encompassing the full spectrum of battle, from the strategies that mold a war to the tacticians who fight on the land, sea and air, Williamson Murray and Allan R. Millett, two of the country’s premier military historians, present arguably the best single volume of World War II. In describing the “origins of a catastrophe,” Murray and Millet appropriately label World War II as “a clash of nations that had tumbled empires and destroyed a generation.” In the course of the 20th century and arguably the history of the world, no war looms as transformative or as destructive as WWII.

From Hitler’s dream of Anshlus to his quest for Lebensraum to the surrender of Japan, A War to Be Won is every bit a complete synthesis of the war. The book explores the causes of the war and takes the reader on a chronological, thematic and geographic tour of the battlefield. Interjecting chapters on war crimes and the “aftermath of war” makes this tightly written and comprehensively researched volume a true masterpiece. A War to be Won is quite possibly one of the best military nonfiction books of this century.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments