By Norman Wickman, as told to Pauline Hayton

Pauline Hayton was 52 years old before her father, Norman Wickman, talked about his life in the British Army, and what happened in Dunkirk as he saw it. It was 1999. Wanting to write a family memoir, Pauline pumped Norman for information on his childhood; his wartime stories spilled out instead. She found them so fascinating that she put the memoir to one side and concentrated on capturing his every word. This is his experience at Dunkirk as told to Pauline, supported by her research.

In 1939, I was 20 years old, married, father of a young child, and struggling to make ends meet. To improve the family’s finances, I enlisted in the Army, figuring that when my six months of national service ended I would be 21 and entitled to earn adult wages instead of the youth’s wages I was then earning—a good plan, I thought, until foiled by Britain’s declaration of war against Germany. The bad news was that my six months of army life stretched to seven years in 62 Chemical Warfare Company. The good news was that in those seven years I was involved in only seven weeks of combat. Three of those weeks were during the devastating defeat of the British Army at Dunkirk.

On April 26, 1940, truckload after truckload of Royal Engineers filed out of the camp gates, heading for the Southampton docks, where we embarked to cross the English Channel to Le Havre, France. Our job was to clear airfields of equipment left behind after British planes had been returned to England. No one was the least bit concerned that we might end up fighting Germans. After all, the British Expeditionary Force had been in France since September 1939, with not one shot fired against the enemy. We moved across France from airfield to airfield, heading toward the Maginot Line. But we never got that far.

On May 10, Germany invaded the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg, which triggered a rush into Belgium by the British Expeditionary Force and the French Army, unwittingly playing straight into the enemy’s hands. With the best British and French fighting troops diverted to the north, the way was open for the German Army to flank the Maginot Line. Achieving what was considered impossible, German Army units, with almost 2,000 tanks, made their way through the hilly, densely forested Ardennes region. Using terrifying blitzkrieg tactics, the German Army swarmed into France at Sedan on May 13, then turned northwest, heading toward Boulogne, the channel ports, and the sea.

Our 62 Chemical Warfare Company was ordered to Arras to join regiments assembling to oppose the advancing German forces. Enemy planes dropped leaflets on British troops, warning that any soldier found with poison gas would immediately be shot, as would all Royal Engineers. Despite the ominous warnings in the leaflets carried, we burst into laughter, and owing to the shortage of bathroom tissue the leaflets were put to good use.

Concerned about German threats and the deadly outcome for the men should the poisonous gases we carried be hit, our officers ordered the disposal of the lethal concoctions. At the deserted village of Lattre St. Quentin, we found deep cellars under the houses. Sappers (Royal Engineer privates) toiled for three days, burying the chemical weapons in the cellars and then imploding the buildings, safely sealing in the gases.

General Heinz Guderian’s panzers rapidly rolled west. On May 20, his army traveled 40 miles in 14 hours, taking Amiens and reaching Abbeville, cutting the Allied forces in two. Almost one million soldiers of the British Expeditionary Force, French, and Belgian armies were trapped in Belgium and northern France. Pulverized by the aggressive German advance in Belgium, our battered forces retreated toward the French border. Days were spent fighting, and under the cover of darkness we fell back behind some river or canal to prepare to fight again when daylight arrived.

My company had not yet come into contact with the enemy, nor been involved in any fighting, but this did not stop me from finding a pot of paint and decorating my water truck. “Berlin or Bust,” I advertised to the world with all the bravado and confidence of an invincible young soldier not yet baptized in battle. Before reaching Arras, 62 Chemical Warfare Company Company was ordered to Béthune. It was a slow, difficult drive along roads congested with thousands of fleeing civilians.

On May 21, Allied forces made a counterattack against General Erwin Rommel’s panzers south of Arras. The battle continued for two and a half days, but on the night of May 23 the British were forced to withdraw. However, the counterattack had not been in vain. By delaying the German advance, four British divisions and a large part of the French First Army were able to withdraw toward the channel coast. We were in Béthune. The counterattack gave us extra time to prepare for the demolition of the many bridges spanning the La Bassée Canal in order to further delay the Germans.

While the sappers laid explosives on the bridges, I was given the job of dispatch rider, carrying messages between the various army units as commanders attempted to organize a collective withdrawal before the bridges were blown. Sergeant Wellington warned us that dispatch riders were a favorite target for German snipers who were operating in the area. He ended his briefing by wishing us, “Good luck.” But good luck had not been with me that morning. Unsuccessful in delivering my dispatches thanks to a sniper’s bullet creasing my forehead and ripping my epaulet to shreds, I lay in the dirt of a country lane, playing dead.

After 30 minutes and hoping I would be safe, I jumped onto my motorcycle and tried desperately to kick start the machine. Finally, the motorcycle roared to life, and I raced back to my unit. Having reported the sniper, my thoughts turned to Ivy, my young wife, who had almost become a widow that morning.

By May 24, the enemy had taken Boulogne. Calais was cut off. German advance units had reached the Aa Canal, a mere 12 miles west of Dunkirk, the sole port remaining in Allied hands. The Allied northern forces—comprised of the British Expeditionary Force, French, and Belgian troops—had managed to withdraw from Belgium to the French frontier. To the east, west, and south, there were German divisions. Only one way was open for withdrawal, north to Dunkirk. In a situation that was rapidly becoming desperate, we were placed on half rations.

By holding back the enemy at Arras, the British Army had given us time to prepare 22 bridges for demolition around Béthune. The hordes of refugees trying to cross the bridges made the work difficult. Seeing the problems they caused and fearing fifth columnists could be in their midst, officers ordered that refugees be stopped from crossing the bridges. Turned away from one bridge, the civilians hurried north to another and another until they found one they could use to cross to safety to the east bank of the canal—a forlorn hope. The corridor of safety between the German front lines in the west and the front line in the east was a mere 15 miles. Squeezing this small pocket of safety, the German forces surrounded the trapped Allied divisions, who by now were fighting with their backs to the sea.

I Closed My Ears and Mind to the Horrific Screams of Dying and Wounded Men by Focusing on the Tens of Thousands of British Soldiers Whose Lives Depended on Us Doing Our Job.

Orders were not to blow the bridges until the enemy was in sight or the growl of tanks moving up could be heard. It was a race to stop them storming across the rivers and canals. Once the way forward was blocked to the enemy, we would fall back to the next bridge. Was it only two weeks ago when we had been pottering about on the airfields? It all seemed totally chaotic. At one bridge we barely had time to prepare the detonator and hide around a corner before German panzers started to cross. The bridge was blown. I closed my ears and mind to the horrific screams of dying and wounded men by focusing on the tens of thousands of British soldiers whose lives depended on us doing our job.

At another bridge, an advance unit of German soldiers had arrived minutes before us. Hurtling from our trucks, we hid in doorways and behind corners. All we had were rifles, machine guns, and a desperate determination to drive back the enemy. A fierce exchange of rifle fire ensued. I was at the back of the convoy and ordered to protect the rear. As I was beginning to wonder if we would be lucky enough to make it to the far bank, the bridge was captured just long enough for charges to be set while we raced across in our trucks. Then it was blown to smithereens.

The enemy was hot on the heels of our retreating Army. At one bridge, trucks raced across while under fire from enemy rifles and machine guns. Last in line with my water tanker. I had barely left the bridge before a brave soldier, driving a truck full of explosives onto the bridge, tore past me, scraping the front of the tanker. Looking in my mirror, I saw the truck screech to a halt on the bridge. The driver leaped out and ran back toward me.

By now I was reversing toward him with the passenger door swinging open. “Get in! Get in!” I yelled. The soldier needed no encouragement. Under a hail of enemy bullets, the heroic man hung onto the front passenger seat, his legs dangling outside the cab as I whisked him away to safety while 62 Company provided cover. Enemy armored cars rushed the bridge before it was destroyed. But they were too late. With a tremendous roar, the truck exploded, demolishing the bridge and the armored cars on it.

The Royal Engineer companies were to withdraw to Dunkirk, blowing bridges at Merville, Merris, and Méteren on the way. The roads were awash with the flotsam and jetsam of war in full swing. Leaderless, defeated French soldiers trudged north away from terrifying German attacks. French villagers, panicked by the sight of the defeated soldiers, abandoned their homes to join the heaving crowds blocking the roads. British troops were held up for hours as they struggled to reach the east bank of the Aa Canal to form a front line on the western edge of the escape corridor.

At Lille, the French First Army blocked the enemy advance, holding them at bay for three days, tying down seven German divisions while 150,000 trapped Allied soldiers swarmed to Dunkirk, where the evacuation was making a slow start. As I pushed north along the crowded roads, my heart went out to mothers slogging along with their children. Bodies—men, women, children and horses—lay by the roadside, among abandoned vehicles, testimony to some Stuka dive bomber pilot’s foray along the road.

The Royal Engineers, along with other specialist units, were formed into special detachments. My unit was “Pol” Force. The others were “Mac” Force and “Petre” Force (a total of 360 men). We were sent to Mont des Cats, a 500-foot hill on the Belgian border, with orders to protect the flank of the retreating army. I felt we were scrambling around like lunatics; everything seemed complete confusion.

Fighting their way north had been a bloodbath for the Royal West Kent Regiment caught in a valley by mortar fire. Suffering heavy casualties, they needed our trucks to transport the wounded to Dunkirk. Grimly, we looked on as mutilated soldiers, eyes glazed in shock, uniforms saturated in blood, were helped into the trucks. Aware that when the time came for our withdrawal we would have to cover the 22 miles to Dunkirk on foot, a thought struck me like a bolt of lightning.

“Do they think we’re not going to need those trucks because we’re not going to make it through whatever Gerry’s got for us?” I asked my best friend, Darky.

“Nah,” said Darky, with a show of bravado. “They reckon we’ll still be fit enough to run all the way to Dunkirk after we’ve sorted Gerry out.”

Crossing the fields to Mont des Cats, we walked straight into a mortar attack. Dead and wounded men fell all around. I gagged at seeing Major Thomas’s knee blown off. Captains and lieutenants urged us forward. Soldiers and medics scrambled to drag and carry the wounded toward the hill, where they were taken to the Trappist monastery on the summit. I was still shaking as we climbed the hill and settled ourselves into hollows by the roadside. Darky and I stayed close together. We both agreed it was a bad do.

So far, we had seen little fighting. Puffing on his pipe, a young lieutenant walked among us. In a calming voice, he reassured us. “Don’t worry about the Germans when they come along. We’ll just have to take them on. That’s what we’re here for. We have to hold this position for 48 hours to allow as many of our men as possible to withdraw to Dunkirk. They’re depending on you. I know you won’t let them down. In the meantime, just settle down and have a rest and a smoke.”

Darky and I felt we were up the creek without a paddle. To cheer Darky, I rashly promised to buy him a pint of beer when we returned home. There were 80 men in my area of the hill. Transfixed, we watched the German Army’s arrival on the plain below. There before us was the enemy, flagrantly displaying its superior fighting power. It was soon brought to bear on Pol Force. That first afternoon, artillery fire pinned us in our hiding places but caused little damage. With the coming of night, the guns fell silent, and we snatched what little sleep we could.

May 28 began with a dawn attack by the Luftwaffe. Roaring planes emerged from the early morning mist, dropping bombs and strafing Pol Force’s positions. Time and again they left only to return for more menacing sorties. Earth and gravel splattered us, but the planes’ inaccuracies resulted in few casualties. Morale remained high. Derisive laughter spread contagiously from hollow to hollow. “Get your eyes tested, Gerry! Can’t you get your sights sorted out?”

Throughout the rest of the morning, a tremendous concentration of firepower was brought to bear on our positions. The lieutenant bolstered us, telling us the German commanders had no idea how many brigades were entrenched on Mont des Cats, blocking their advance into the escape corridor. “They’re trying to flush us out to assess our strength. Stay calm men. So far, you’ve come through it all without them inflicting any real damage on us.”

“They’ve shot the pipe out of my mouth!”

Then came the rumble of approaching tanks. As the tanks neared, we became jittery. We hastily prepared petrol bombs and threw them when the tanks closed in. One man, leaving his hiding place to dash out and hurl the bombs, slipped and fell to be crushed beneath the squeaking tracks of a panzer. We lobbed burning bomb after burning bomb at the massive bulk of these monsters until voracious flames licked at tracks and turrets, forcing the tanks to turn and bolt down the hill.

Late in the afternoon, the German infantry appeared. We watched as they crept up the hill then opened fire, resulting in a rapid exchange. In the confusion, the lieutenant’s pipe was shattered by a German bullet. The pipe fell from the shocked officer’s mouth followed by a bellow of rage. “They’ve shot the pipe out of my mouth! Bugger that! Fix bayonets! Up and at them men! Scatter them!”

And so I was introduced to my first experience of hand-to-hand combat. We charged down the hill, yelling like Ancient Celts. We must have looked like we meant business because the Germans fell back. I ran toward one reckless soldier still charging up the hill in a bayonet attack and shot him in the head. Running past him, I was relieved to find the German had fallen face down in the dirt. I would not have to see the face of the first man I had personally killed. After only a few minutes, the German soldiers turned and ran. Triumphantly, we congratulated ourselves then returned to our hiding places.

When German troops withdrew from that part of the hill during the night, our officers seized the opportunity to order a withdrawal. “Men, you are now relieved. It’s every man for himself. Make for Dunkirk as fast as you can. Good luck.” Crossing the dew damp fields, we ran straight into a German reception committee using box formation mortar fire. I saw the pay corporal’s head blown off. Captain Chamier went down minus a leg. And I ran. I ran for six miles before stopping, one of only 87 survivors of the 360 defenders of Monts des Cats. As I struggled to regain self control, seven more survivors arrived. No one knew if Darky or any of my other close friends had escaped.

Unsure of the way to Dunkirk, we followed refugees heading north. Later that morning, Stuka pilots flew up and down the road in an orgy of death and destruction as people dived into ditches for cover. Three hours later, we rested, ate bully beef and hard tack, then dozed on blankets spread in the shadows of a farmhouse wall. A Stuka screamed down from the clouds, spraying bullets as it passed only feet above our heads. The bullets tore a row of holes in the blanket alongside my body. Two of my companions were killed where they slept.

Covering the dead with blankets, we moved on, coming across three heavily bandaged British soldiers, who had decided they were not going to sit around and be taken prisoner. Too weak to continue on foot, they were leaning against a broken down ambulance. We took turns working on the engine and handing out chocolate to tired, bewildered children passing by in the crowds. Suddenly, the engine erupted into a shaky roar. Everyone piled into the ambulance. A feeling of optimism filled the vehicle.

Then, after we had driven for a couple of miles, Stukas appeared. The attack killed five of the group, including the wounded, and damaged the ambulance beyond repair. Those of us still alive continued the march, rendering any abandoned rifles we found useless to the enemy by removing the bolts and dumping them in the rivers. We came across fields full of vehicles, weapons and equipment, burned and destroyed by our own Army so they would not fall into enemy hands. Finally, we arrived at the bridgehead at the Burgues-Furnes Canal, from where we were directed to the beaches at Bray-Dunes rather than Dunkirk, which was a burning shambles thanks to German bombing.

With twilight approaching, our small group of four stepped onto the beach at Bray-Dunes. Tens of thousands of exhausted troops congregated on the golden sands with not a spark of fight left in them. Other soldiers formed long lines out to sea. Only their determination to reach home, a mere 22 miles across the English Channel, kept them waiting patiently for rescue boats. They stood chest deep in water, oily and slick from the shipwrecks offshore. Here and there, a body floated, a remnant of the human cargo lost to German bombs. An occasional victim of strafing and shelling littered the sand. The sickly sweet stench of death lingered in the still air.

I surveyed the beach, trying to make sense of the scenario before me. Slowly, understanding dawned. Disbelief, horror, then anger welled up, followed by intense shame. Until that moment, I had believed we were an Army in retreat. Now, I realized, I belonged to a defeated army. My pride fought against accepting this fact. I still had plenty of fight left, but looking again at the thousands of dejected men, I could see these soldiers had had it. I was filled with confusion and despair.

We settled in the sand dunes, ate some hard tack and smoked cigarettes. And we waited. We had reached the coast. Now what? We soon found out. German spotter planes flew overhead dropping illuminated parachutes to light up the area for German gunners. The muffled explosions of shells hitting the beach and all areas around us disturbed the night. Mercifully, with the sand absorbing the shock of the explosions, the shelling caused little damage apart from men losing sleep. I nestled low in the dunes wondering how we had gotten into this mess.

As I tried to sleep, the day was ending with 10 German divisions pressing on the Dunkirk perimeter, now a mere 20 miles long and six miles wide. I was right. We certainly were in a predicament. It was just as well that I did not know how bad a predicament it was.

On May 17, Winston Churchill, the new prime minister since Neville Chamberlain’s resignation on May 10, had begun to consider the possibility of evacuating the British Expeditionary Force from France. He did not believe it would come to this, but every contingency had to be faced. Although nobody realized it, some groundwork had already begun. A May 14 radio broadcast called on all small boat owners to send their particulars to the Admiralty. Boat yards were building wooden minesweepers because of the magnetic mine threat. Consequently, the Small Vessels Pool, unable to obtain the boats it needed, intended to requisition private yachts and motorboats. The War Office originally felt no sense of urgency regarding plans for the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force and assured there was ample time to organize for such an unlikely event. The Admiralty put Vice Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsey in charge of the evacuation plans, codenamed Operation Dynamo.

The speed of the German advance through France to the channel ports of Boulogne and Calais took everyone by surprise. The evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force quickly became top priority. The original 36 vessels allocated to the Admiralty would not be enough. What Ramsey needed was every seaworthy craft in the nation. The Ministry of Shipping searched for vessels capable of bringing the men home — passenger ferries, barges, drifters, trawlers, coasters, dredgers, fishing boats, lifeboats, tugs, anything. Not knowing what to expect, many crews readily volunteered to go across the channel to Dunkirk.

On the morning of May 26, up to 4,000 German bombs rained on Dunkirk and the thousands of troops pouring into the area. The British government, realizing that the troops were on the brink of a catastrophe, ordered Admiral Ramsey to commence Operation Dynamo. He had 129 vessels with which to evacuate hundreds of thousands of troops. The Admiralty expected to save only 45,000 of them during the next two days. Even this modest calculation fell short as rescue vessels encountered the enemy. Damaged ships turned back or sank, sometimes with their loads of evacuated troops. By midnight on May 27, only 37,965 men had been saved.

Receiving reports about the increasing numbers of men waiting on the beaches, Ramsey desperately called for destroyers, minesweepers, everything he could get his hands on. Captain William G. Tennant was ordered to Dunkirk to organize the loading of the rescue fleet. With him went a naval shore party of eight officers and 160 men. Arriving in Dunkirk at 5:30 pm on May 27, he explored evacuation possibilities. Evacuation from Dunkirk harbor was not feasible; continual bombing had left it a blazing ruin. He decided the beaches east of Dunkirk were the best bet. He conferred with army officers, who estimated the Royal Navy had 24-36 hours before Dunkirk was overrun.

Tennant signaled Dover to send every available craft east of Dunkirk. Naval parties rounded up soldiers and sent them to the beaches. Learning that leaderless soldiers were becoming unruly, Tennant went to speak to the men and appealed for calm and discipline, reassuring them that plenty of ships were coming to take them back to England. Responding to his authority and leadership, the men calmed down.

There Were 5,000 soldiers, Mostly Without Officers or any Leadership and Degenerating into Drunken Mobs on the Beach at Bray-Dunes

Concerned that far too few men were being lifted from the beaches, Tennant requested information from his commanders. They told him the entire stretch of beach from Dunkirk to La Panne shelved so gradually that destroyers and large vessels had to anchor a mile off shore, even at high tide. They also did not have enough small craft on the scene. Destroyers were having to use their own boats to pick up the men from the beaches and ferry them to the destroyers. When the launches arrived, the scared troops rushed to scramble in from where they stood in deep water and more often than not capsized the boats. It was taking hours to lift only a few hundred men off the beaches. Back in Dover, the operations room was awash with messages from the destroyers urging them to send more small boats.

Returning to the harbor, Tennant again studied the area. He knew he could evacuate men faster if he could use the docks, but that was out of the question. Then, he noticed that the Luftwaffe was concentrating on the docks and completely ignoring the moles, two long breakwaters that formed the entrance to the harbor. One from the western side and one from the east reached out toward one another, leaving a narrow gap with only enough room for the passage of one ship. The eastern mole, 1,400 yards long, was constructed of rock with thick concrete pilings alongside it. On top, a wooden walkway with wooden railings along the edges ran the full length. It was just wide enough for four men to walk abreast.

Tennant estimated that the tides rose and fell 15 feet around the mole, which could make transferring troops at low or high tide hazardous, and berthing could be dangerous if the swift tidal currents slammed the vessels against the wooden planking. The mole was not built to take such a battering. Would it prove sturdy enough to act as a pier? There was only one way to find out.

Tennant ordered a ship to come alongside. In no time at all, this first vessel crammed 950 men on board. At 4:15 am on May 28, it set sail for England. Sadly, a German plane sank the ship less than halfway across the channel, but Tennant had made an important discovery. The mole worked. It not only worked, it could accommodate several ships at a time.

Tennant ordered all vessels to the eastern mole, a decision that would prove to be the turning point at Dunkirk and the salvation of the British Expeditionary Force. Clouds of oily black smoke, belching from the burning oil refinery, hung low over the harbor, hiding the mole from view. That day, there should be no interference from the Luftwaffe.

Informed there were 5,000 soldiers, mostly without officers or any leadership and degenerating into drunken mobs on the beach at Bray-Dunes, Tennant sent Commanders Kerr and Richardson with 40 men to Bray-Dunes. Commander Clouston, a tall Canadian, was put in charge of the mole.

Arriving at Bray-Dunes that evening, Richardson alerted Dover that he had found not 5,000, but 25,000 men on the beach and that small boats were urgently needed. In the early hours of May 29, with a storm drawing near, the seas became too rough for evacuation from the beaches. Richardson sent the troops to the mole at Dunkirk, only seven miles away, but a marathon for men at the end of their endurance and scarcely able to walk.

After being put into use, the eastern mole proved to be a great success. Destroyers picked up between 500 and 900 men in minutes and quickly took them to Dover before returning to the mole. Towering head and shoulders above the crowds, Commander Clouston shouted instructions through his megaphone, skillfully controlling the flow of troops to the streams of arriving ships. Two thousand men an hour were leaving from the mole. On May 28, a total of 18,527 men safely left France, more than double the previous day’s number.

As news of the evacuations at the mole spread, thousands of soldiers converged on the area. On the morning of the 29th, a steady stream of ships pulled in, quickly loaded, and pulled out. No matter how many men boarded, the lines of waiting soldiers continued to grow. The line stretched the length of the mole and snaked back along the beach. Brigadier Parminter, working alongside Commander Clouston, used a hat-check system. He divided the waiting men into groups of 50, gave each group a number, and as the number was called, the group stepped out onto the mole. At times, the embarkations were going so smoothly that the men trotted along the mole at the double. It was a heartening improvement.

Around 1:30 pm, a change in wind direction sent the heavy pall of smoke inland, allowing perfect conditions for the 400 German aircraft heading for Dunkirk. As the 12 vessels at the mole lost their protective cover, German pilots saw them from overhead. Bombs poured from the skies. The mole was hit. Chunks of concrete hurtled into the air. Swooping down, Stukas machine-gunned troops caught on the crowded walkway. Defenseless and with nowhere to hide, they were easy targets.

Hundreds of lives were lost and numerous ships damaged or destroyed as they frantically tried to leave the mole. Two ships sank at their berths. At dusk, after 90 minutes of continuous bombing, the raid ended. In places, the mole was left with more holes than a rabbit warren, but only the outer side of the mole was obstructed by wreckage. The inner wall was still clear. Shipping losses on this day were three destroyers and 21 other vessels, with many others damaged. Despite everything, 47,310 men returned home safely.

Responding to a public appeal, small craft were brought to Ramsgate from all over the south and east coasts and the River Thames. They came from yachting centers, boatyards, and private moorings to join the naval vessels. Owners, many only weekend sailors, insisted on going with their boats. Members of yacht clubs volunteered. Leaving their desks and places of work, civilians came from all over the south of England. Facing grave danger, these unassuming heroes risked their lives to save men caught in a desperate plight. Some used their day off work to save hundreds of lives and then returned to their desks as usual the following day.

Most small boats were towed across the English Channel. Few of these little vessels were built for use at sea, but the channel was kind to them, remaining still and calm while they plied back and forth between the beaches and the larger vessels. The small boats provided the only means by which soldiers on the beaches could reach the rescue ships moored far off shore. Some volunteers worked continuously for 48 hours at a stretch before returning to Ramsgate when fuel ran out or they had become too exhausted to carry on.

Only eight small boats were in the first convoy that set out across the channel at 10 pm on May 29. Gradually, the numbers increased until it was impossible to tell where one convoy ended and another began. Nearly 400 small craft were involved in the rescue operation. By the time Operation Dynamo ended, they had been instrumental in saving almost 100,000 men from the beaches around Dunkirk. Newspapers and broadcasters rushed to tell the story of these heroic volunteers bringing a surge of pride in the British population. Morale soared. The “Dunkirk Spirit” developed. People were energized, hopeful, and eager to be actively involved in the war against Hitler.

“The Enemy’s Pounding at the Door, and We’re Just Sitting on Our Arses in the Sand Dunes”

As the residents of Dover listened to the thunder of guns at Dunkirk and the evacuation was making headlines in Britain, I woke to a dull, cloudy day. I was amazed to see the lines of men still standing in the sea. My friends and I wondered if any were getting away. A soldier reassured us the Navy was going to rescue everyone. Although I desperately wanted to believe him, the soldiers milling around the area seemed fearful and uncertain.

Skulking in the dunes, we could see little evacuation activity. In fact, the only activity was from German Stukas flying along the beach, dropping bombs and strafing our besieged troops. “The enemy’s pounding at the door, and we’re just sitting on our arses in the sand dunes,” growled one of my companions. With glum expressions, we watched and waited.

At mid-morning an officer from the Royal Engineers stumbled across our group. Telling us we were needed to repair bomb damage to the eastern mole at Dunkirk harbor, he put me, a corporal, in charge with orders to find more sappers and report to the commander at the eastern mole. I was relieved to have something positive to do and that someone seemed to know what needed doing. We found 16 sappers to swell our ranks, and then off we marched to Dunkirk.

Coming to the outskirts of town, we looked on in disbelief as we witnessed the scene unfolding before us. Four French officers were standing with their troops when a black Citreon screeched to a stop beside them. The officers jumped in, and the car sped off down the road. We were disgusted by this abandonment of the French soldiers who were in a sorry state. Their uniforms were ragged; some men were without boots. Gaunt faces and despairing eyes testified to the horrors they had been through. With their officers gone, they became distressed and fearful, asking each other, “What do we do?” “Where do we go?” I approached the men. One or two spoke a little English. With few words and much gesticulating, they understood my message. “Go to Bray-Dunes. Find a British unit that will take you in. They’ll look after you.”

Moving into Dunkirk, we found the harbor and the eastern mole. The day’s heavy mist offered protection from the predatory Luftwaffe. There would be no air attacks in these conditions. On the mole, the atmosphere was cheerfully relaxed. Evacuations were proceeding safely and efficiently. Reporting to Commander Clouston, we were told to find whatever we could to repair the mole’s walkway, severely damaged after the previous day’s savage air attacks.

We foraged for materials in Dunkirk. This was highly dangerous. The Luftwaffe was still delivering bombs, and German batteries in Calais were firing salvoes into the town. Miraculously, the mole lay just out of reach of the guns. Choking, black smoke filled the air as we moved off through streets filled with debris, burned trucks, and downed trolley wires. Without tools or transport, we salvaged repair materials, making trip after trip, carrying beams, floorboards and doors taken from damaged buildings. It was a good day’s work, not only for the Engineers, but also the Royal Navy. A total of 53,823 men were rescued on May 30.

We worked until dark before proceeding to the beach at Malo-les-Bains, a mile to the east. Munching on hard tack, we discussed our situation. I was pleased to be busy, which kept my mind off the dilemma we were in. Others were hopeful of getting away after seeing how many men had been evacuated. I was more realistic, believing we were doing such a useful job for the evacuation we would be there until Dunkirk was taken.

We spent another sleepless night disturbed by exploding shells as we hid in the dunes. In the morning, we found a canal to wash our faces. Seeing some men were not shaving, I told them to shave to keep up standards and morale. “What’s the point?” they argued. “We’re all going to be prisoners of war soon enough.” I thought they might well be right.

May 31 was again misty and overcast, perfect for keeping the Luftwaffe on the ground. But these weather conditions did not stop the shelling of Dunkirk. Having found their range, batteries planted east of Gravelines began damaging ships berthed at the mole. For the soldiers, the dash to the waiting vessels was unnerving. During the worst of the attacks, frightened men tried to move back off the mole, but discipline was strictly enforced by the officers. The men were made to run the gauntlet, sometimes at gunpoint, sometimes without making it to the ships.

We watched as British destroyers sailed westward past Dunkirk. They fired salvo after salvo at the German batteries at Gravelines, pounding the enemy guns until they fell silent. Then we returned to the work of repairing the mole. We were more fortunate than most of the weary men around us. We still carried our rifles and rucksacks containing a few more days’ supply of hard rations. Some of the men waiting to evacuate had not eaten for days. Before the day ended, 68,014 men arrived in England.

The sun was burning off the early morning mist, promising a clear, sunny day. June 1 also promised to be a day made in hell as German bombers took advantage of this break in the weather. At 5:30 am, German Messerschmitt Me-109 fighters swept in from the east. I nudged the men awake to wash and have more hardtack for breakfast before going to the mole. Protesting and grumbling, the men were lying flat on their stomachs, stretched over the edge of the canal, about to splash water into their faces when the planes appeared. Before they could rinse the sleep from their eyes, the beaches were awash with the slaughter of troops mowed down by machine-gun fire. We looked at the bodies strewn along the beach, sickened by the carnage, the men relieved I had forced them to move.

Arriving at the harbor, we looked on in horror. Gun flashes and columns of smoke rose over Dunkirk as planes attacked the destroyer Windsor, which was berthed at the mole.

By 5 am, the Royal Air Force had 48 Supermarine Spitfire fighters heading toward Dunkirk. Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding was trying to spare British planes from further losses, so the protection was spasmodic. British fighters flew only four short patrols a day. By the time British planes crossed the channel, they had only enough fuel to engage the enemy for 40 minutes before returning home. Pilots often made four sorties each day, but to the men on the beaches who were experiencing unrelenting Luftwaffe attacks, it felt as if the Royal Air Force had abandoned them. Few soldiers saw anything of the pilots’ heroic battles taking place high above them.

The 5 am patrol brought down 10 German planes before returning to England. It would be 9 am before another patrol was sent to the French coast. During this period between patrols, the Luftwaffe ruled the skies. As destroyers and minesweepers sailed with their troops from the beaches and the mole, they were bombed by Heinkels and Stukas. When 40 Stukas appeared in the sky, every gun in the British fleet opened fire, but by 8 am, the destroyer Keith was hit. The Stukas returned for second, third, fourth, and fifth attack on the Keith before she finally sank at 9:15 am. From the mole, we saw the French destroyer Foudroyant, full of rescued troops, turn over and sink in seconds, victim of another swarm of Stukas.

German air attacks faded away when the Spitfire patrols were in the vicinity, but there were four more periods during the day when the Royal Air Force could not provide fighter cover. The Luftwaffe made the most of them, destroying or damaging 17 ships on June 1. Hundreds of men perished in the Luftwaffe frenzy. Through it all, we went about our work repairing the mole.

So, I jumped. Immediately, I Realized I had Made a Big Mistake.

Commanders in London, Dover, and Dunkirk felt increasing trepidation at the escalating destroyer losses. The decision was made to stop using Royal Navy vessels during daylight hours. At 1:45 pm, all destroyers received orders to return to England immediately.

Commander Allison of the destroyer Worcester was entering Dunkirk harbor when the message arrived. Deciding it did not make sense to return to Dover empty, he berthed at the mole. I watched as lines of soldiers disappeared onto the destroyer. Brigadier Parminter, aware this would be the last vessel until nightfall, told me to get myself and my men onto the destroyer. “We’re going to need men like you back in England to continue the fight,” he said.

Urging the men along the mole, I took a last look around, making sure everyone had gone, and then raced down the walkway. The destroyer was pulling away from its berth. I hesitated. The gap was too wide. “Jump, you silly bugger, jump!” yelled a burly sailor at the ship’s rail.

So, I jumped. Immediately, I realized I had made a big mistake. In mid-air, I glanced down. The foaming water churned wildly where the destroyer’s sharp propeller blades were waiting to chop me to pieces. Leaning far out, the muscular sailor grabbed my shredded epaulette, flapping loosely from my uniform. With a crash, I slammed against the ship’s rail. Using brute strength, the sailor hauled me over, where I fell in a crumpled heap on the deck. Unbridled joy and relief overwhelmed me. I was on the destroyer, safe and on my way home. Then, all hell let loose.

“Get up against the bulkhead,” shouted the sailor. Stunned and winded, I stumbled across the deck. As I pressed against the gray metal, I heard the planes. Stukas, 30-40 of them, dived on the Worcester time and time again. Bombs rained down like confetti all around the ship. The destroyer, so filled with troops it was top heavy, heeled over wildly at heart-stopping, stomach-lurching angles to evade the falling bombs. Bombs to the rear lifted the stern clear of the water. The massive propellers screamed until the ship crashed down again. Colossal columns of water washed over the ship. I closed my eyes and tried to make my body disappear into the bulkhead.

By some miracle, none of the 100 bombs made a direct hit on the ship. Shrapnel killed 46 and wounded another 180 before the attacks tapered off. As sanity returned, I opened my eyes and looked round. The planes had disappeared. The Worcester, with its crowded decks, was steaming across the channel to the British coast. I may have been exhausted by the day’s events, but I felt exhilarated. I was one of 64,429 men who returned home on this horrific day.

Having failed in battle, we poured off the ships, expecting a cold reception. It may have been a defeated Army coming home, but a jubilant welcome awaited us. The local populace offered friendly smiles and joyous greetings. Better still, the Red Cross and women volunteers were ready with hot cups of tea, cocoa, sticky buns, and sandwiches. Exhausted, bleary eyed and hungry if not starving, we soaked up the warm reception. We smoked the proffered cigarettes and gulped down the hot, sweet tea and sandwiches before dragging ourselves onto the waiting trains.

I pushed forward to give my name and number to the clerks, wanting Ivy to know I had made it back. Then I pushed onto the train, collapsed into a corner seat, and closed my eyes. Darky, squeezing through the crowds into the carriage, noticed me in the corner of the compartment. He stepped inside and nudged me awake. I jumped up, and we pounded the living daylights out of each other’s backs. “Had to make it back,” said Darky. “You owe me a pint.”

As we rested after our ordeal, Winston Churchill’s rousing June 4 “We shall fight them on the beaches” speech united and galvanized the people into action. The deliverance at Dunkirk had brought the troops home, but we were not in good shape to defend the country against the expected seaborne invasion. The British Expeditionary Force had lost almost all of its heavy equipment, transport and personal weapons in France. In 62 Chemical Warfare Company Company all we had was one rifle between seven men and one machine gun per section.

Of the 850 vessels, large and small, that took part in Operation Dynamo, 243 were lost and 45 damaged. The Royal Air Force lost 106 fighter planes, and the British Expeditionary Force lost almost all of its equipment, including 682 tanks, 120,000 vehicles, 2,700 artillery pieces, and 90,000 rifles. Over 68,000 men were killed, wounded, or taken prisoner. Nevertheless, in the nine desperate days of Operation Dynamo, 338,226 men were rescued.

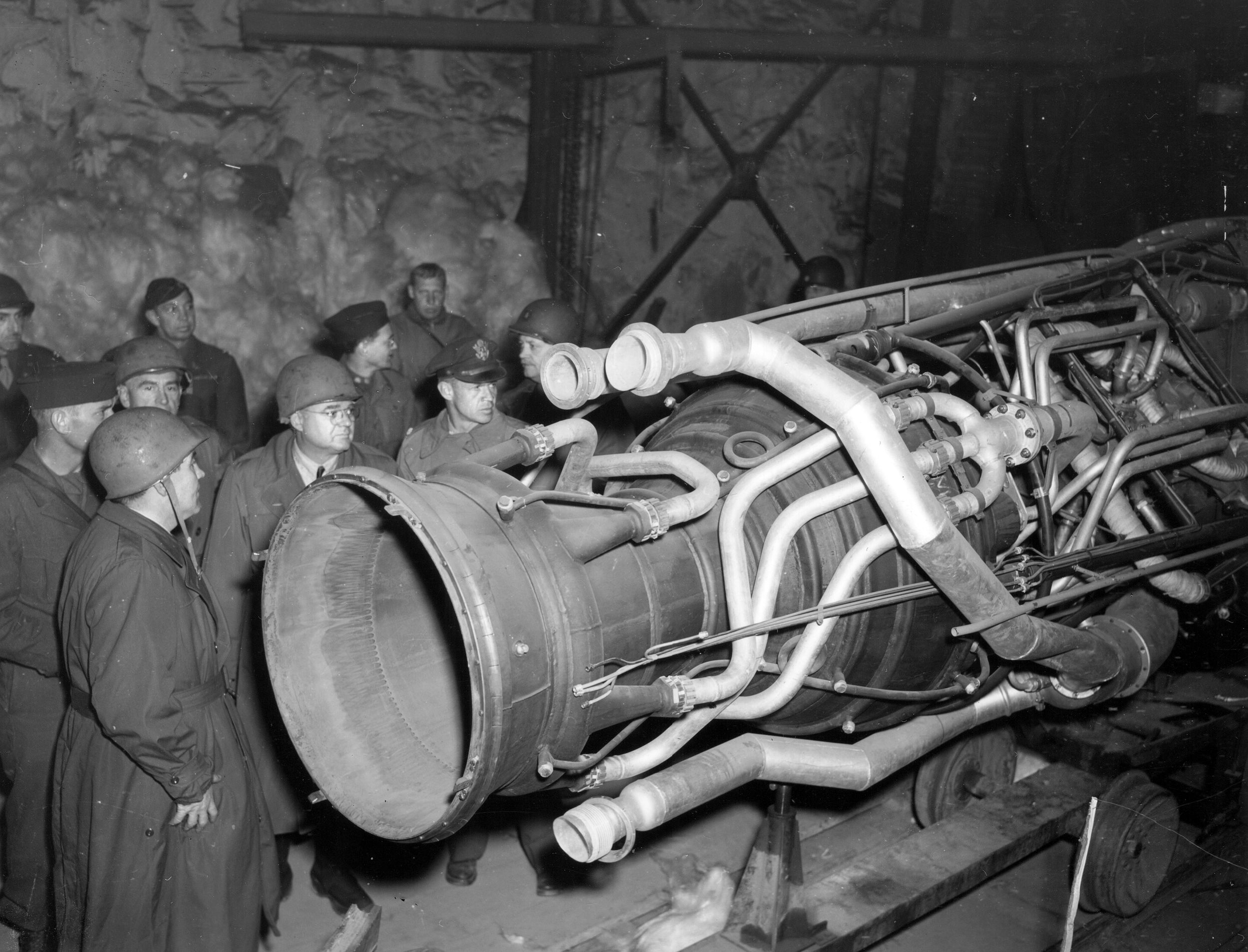

Looking at the photo of three Sappers posing triumphantly during the French campaign, I hate to tell you that that photo was almost certainly taken in Kent! The cottages in the background are definitely English, tile-hung and thus almost certainly in that part of the world.

This photo must, therefore, have been taken just before they embarked fro France, or after they were rescued from the beaches. I think the former, because they look far to chipper!

Unless, of course, it is a still from the old B&W film ‘Dunkirk’, which was all filmed in Kent rather than France (no oasthouses there!) though I doubt it, the men look far too authentic.

Cheers

I agree

My grandfather, Cpl Edwin (aka Edward) Baker 1983441 was in the Royal Engineers and was in the BEF. He was evacuated from Dunkirk but, we understand, “badly knocked about”. On return to England he requested posting to a unit which would not be sent overseas. He was assigned to bomb disposal. He was killed defusing a bomb in May 1941, in Bootle, Liverpool.

This is an extraordinary memoir. I hope to draw on it a little for a book of semi-fiction I am writing, which will include Edwin’s story.