By Flint Whitlock

In the spring of 1945, after more than five-and-a-half years of total, merciless war in Europe––and the deaths of millions of human beings on the battlefields, the bombed-out cities and in the concentration and extermination camps––the carnage and destruction in Europe had finally come to an end.

Dealing with the tremendous number of sick and traumatized liberated survivors of the concentration camps suddenly became a major priority for the U.S. Army. Many had lost everything and everyone. Of those who had lived in countries now under Soviet control, many did not want to return.

The refugees and survivors needed medical care, food, clothing and shelter. Remaining in the camps for the foreseeable future, no matter how marginal the conditions, was the only option for many. The enormous task of determining what to do with the survivors was turned over to the United Nations Displaced Persons Branch.

Defeat left Germany without a functioning government, economy, infrastructure, or a means to take care of millions of its own citizens. The victors would need to help the vanquished rebuild basic water, sanitation, and utility services; businesses, schools, hospitals, police, courts, and other institutions; civil government—and those guilty of Nazi Germany’s crimes rounded up and put on trial.

A Culture of Terror

A few weeks after Germany had surrendered, 40-year-old Ilse Koch was walking with her two little children, son Artwin and daughter Gisele, through the rubble-strewn streets of Ludwigsburg, near Stuttgart, when she was spotted by a former prisoner from the Buchenwald camp, or KLB. He went to the municipal authorities, who then arrested her and brought her in for questioning.

The red-headed Ilse Koch was the widow of SS-Colonel Karl Otto Koch, Buchenwald’s first commandant (he had previously been in charge of the Sachsenhausen camp near Berlin). The couple had lived a life of privilege, unquestioned authority, and debauchery from 1937 until he was transferred by the SS to run the camp at Majdanek, Poland, in 1941. Karl was shot by an SS firing squad in April 1945 after an investigation and trial that found him guilty of skimming funds that should have gone into SS coffers. He had even stolen gold fillings from the mouths of dead prisoners before cremation.

During the Kochs’ tenure as overlords of KL (Konzentratzionslager) Buchenwald, high on a hill overlooking Germany’s cultural capital of Weimar, unspeakable horrors were committed against the helpless inmate population.

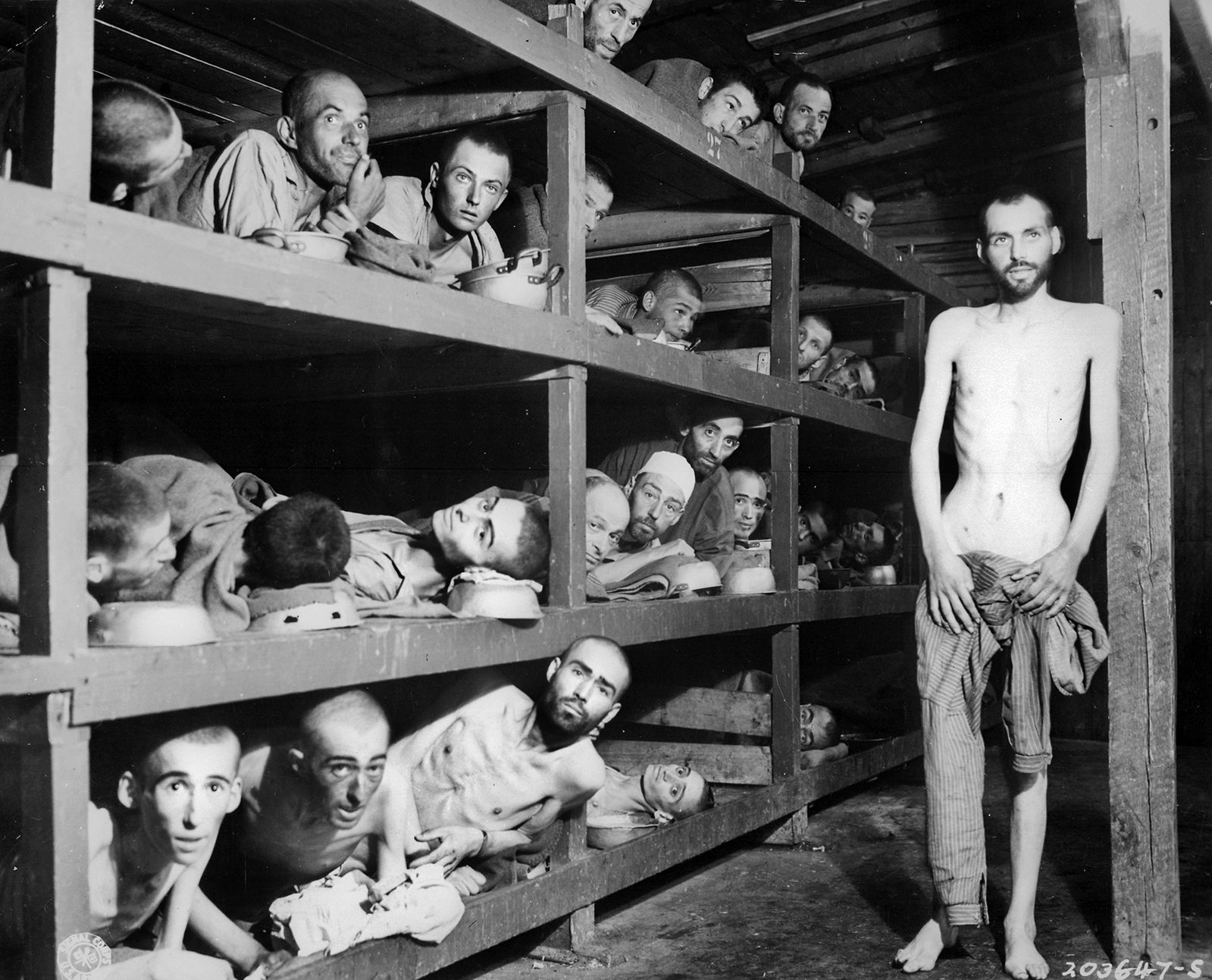

Like all the camps, living conditions were beyond primitive. Prisoners were fed a starvation diet of inedible, so-called “food.” Sanitary conditions were abominable. Inmates were forced to sleep three or four to a bunk. Backbreaking work was non-stop, and many were beaten and tortured by their sadistic SS guards without mercy. Disease was rampant, as was fear and hopelessness.

Prisoners who broke camp rules were hanged on gallows while thousands of others were forced to watch. Those who weren’t hanged were often beaten to death by an especially cruel SS man named Martin Sommer, the camp’s chief jailer.

Another SS man to be avoided at all costs was Koch’s adjutant Heinrich Hackmann, who was known to carry out extreme punishments for little or no reason. One of his favorite punishments was to tie a prisoner’s arms behind his back and then hang him by the arms from a tree or post; the pain was excruciating.

When simply inflicting pain was not enough, Hackmann supervised the random killing of prisoners. On at least one occasion, it was said, he laughingly had two inmates bend back a small tree growing at the lip of the quarry, put another inmate in the tree, and then launch the inmate to his death as though he were a missile on a catapult.

A crematorium within the camp disposed of hundreds of bodies a day.

Although the mother of two children, Ilse was no saint; she carried on an affair with one of the camp’s doctors, and orgies were a regular occurrence at the Kochs’ hill-top home.

She had her passion for horseback riding and would ride around the all-male camp where, it was alleged, she often saw inmates laboring shirtless on work parties. After spotting a prisoner with especially interesting tattoos, the prisoner would disappear. Within a few days inmates would fashion the skin into macabre household objects such as lampshades, knife sheaths, or pairs of gloves. So associated with these barbarities was Ilse that the inmates gave her a secret nickname: “The Bitch of Buchenwald” (die Schlampe von Buchenwald).

Atrocities sometimes involved animals, usually guard dogs that were sometimes sicced on inmates. According to one inmate, Colonel Koch sometimes threw prisoners into the bear den at the camp zoo, where they were “torn limb from limb.”

Ilse Koch was incarcerated, but her turn at justice would have to wait. First, a war-crimes tribunal of the leading Nazis began in the fall of 1945 in Courtroom 600 at the bomb-scarred Palace of Justice in Nürnberg––the city that had hosted the massive, emotionally powerful Nazi Party rallies in the 1930s.

Although some have criticized the proceedings as “victors’ justice,” the “London Agreement” of August 8, 1945, signed by representatives from Great Britain, France, the Soviet Union, and the United States, established the authority for the four powers to create international law and conduct tribunals for those accused of committing war crimes, or “crimes against humanity.”

Adolf Hitler, Joseph Goebbels, and Heinrich Himmler had escaped justice by committing suicide, but there were other high-ranking Nazis and military officers whose ultimate fate would be decided by an international court of law. Twenty-two of the Third Reich’s most notorious figures became the focal point of the first, and most famous, of the war-crimes tribunals, which began in Nürnberg on Monday, November 19, 1945.

In the prisoners’ dock, guarded by members of the U.S. 1st Infantry Division in white helmet liners and Class A uniforms, was a broad cross-section of the former Nazi hierarchy. Military leaders included Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, once the commander of the Luftwaffe and arguably the second-highest-ranking figure in the Third Reich; Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, former Chief of the High Command of the Armed Forces; his Chief of the Operations Staff, General Alfred Jodl; and Grand Admirals Karl Dönitz and Erich Raeder.

Others, who had been a part of the Nazi government included Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess (deemed by many to be mentally ill); former Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop; Wilhelm Frick, ex-Minister of the Interior; and Walther Funk and Hjalmar Schacht, both of whom had served as Minister of Economics and President of the Reichsbank.

Those who were implicated in the program to exterminate the Jews were Gestapo chief Ernst Kaltenbrunner; Nazi Party ideologist Alfred Rosenberg; and Julius Streicher, editor of the viciously anti-Semitic newspaper Der Sturmer. They were joined in the dock assortment of former diplomats and politicanians and Nazi goons.

The tribunal lasted 218 days, and the verdicts read on October 1, 1946. Eleven of the accused were condemned to death, seven were sentenced to long prison terms, and three acquitted.

Sentenced to death were Frank, Frick, Göring, Jodl, Kaltenbrunner, Keitel, Ribbentrop, Rosenberg, Sauckel, Seyss-Inquart, and Streicher. (Göring cheated the hangman by swallowing smuggled poison in his cell.) Martin Bormann, Hitler’s secretary, tried in absentia, was also sentenced to death. Seven men were given prison terms: Dönitz (10 years); Hess (life in prison); Funk (life); Neurath (15 years); Raeder (life); von Schirach (20 years); and Speer (20 years). Fritsche, von Papen, and Schacht were acquitted.

Even today, many Americans assume the trials of the top 22 Nazi figures wrote the final chapter to the 12-year nightmare that was the Third Reich. Such was not the case. A series of less-publicized American military tribunals also took place to prosecute Nazi doctors, judges, industrialists, and individuals.

Out of 3,887 accused war criminals, 1,672 of them later went on trial at the former concentration camp of Dachau. A tribunal for concentration-camp administrators and guards was conducted there from November 1945 through August 1948.

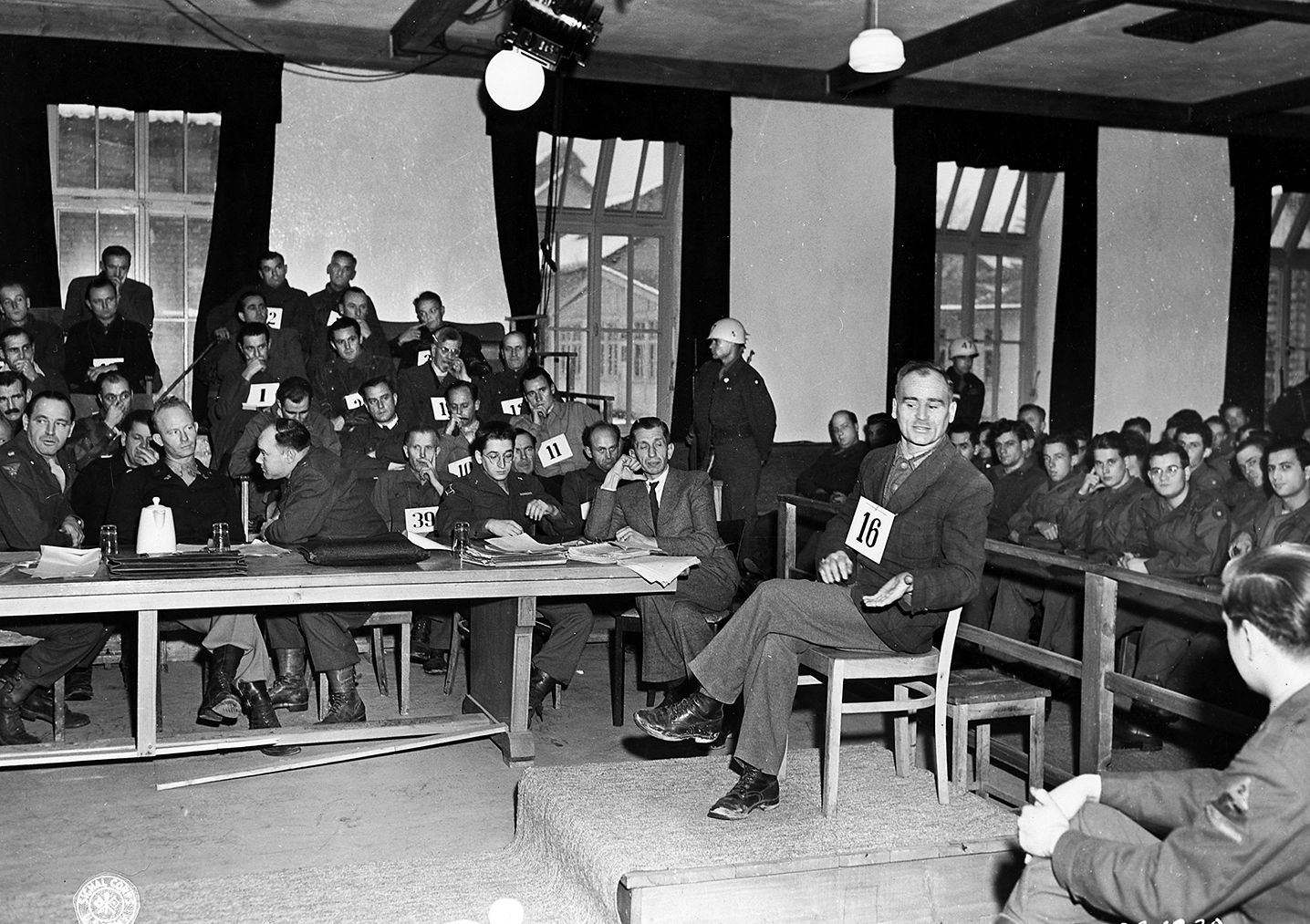

The trials, held in a former mess hall at Dachau, did not conform to customary civilian judicial procedures as practiced in the U.S. and Britain, and were, in fact, akin to military courts-martial, even though not all the accused, such as Ilse Koch, had been military personnel.

Further, those on trial were referred to as the “accused” and not “defendants”—there was no presumption of innocence. It was up to the accused to prove their innocence, not the duty of the prosecution to prove their guilt. All that was required to prove that an accused was guilty was showing that he or she was part of a “common plan,” and that he or she had some connection with the place where crimes had been committed.

On April 11, 1947, exactly two years after KL Buchenwald had been liberated, the most sensational of the Dachau-venue trials began. General der Waffen-SS Josias Erbprinz zu Waldeck und Pyrmont, the senior SS and police commander for the Fulda-Werra Main Territorial District (in whose jurisdiction KL Buchenwald lay), and 30 other defendants who had some association with Buchenwald, including the by-now-notorious Ilse Koch, were prosecuted.

Presiding over the court was 52-year-old U.S. Army Air Corps Brigadier General Emil C. Kiel, who had served as court president of the Dachau war-crimes tribunal. A panel of American military officers, led by Lt. Col. John S. Dwinnell, served as both judge and jury. The prosecutor was William Denson, a former lieutenant colonel, who had graduated from West Point and Harvard Law School.

Only 34, Denson had already prosecuted three such tribunals, and had nearly been overwhelmed by the duty of prosecuting the atrocious crimes.

“The most difficult part of the trial was trying to present a case that the court would believe,” he said, “because the court certainly entertained the same incredulity when they heard my witnesses as I did when I first heard those witnesses. It was absolutely incredible. I didn’t believe it.”

Denson’s first trial took place in November 1945 with the case of 40 accused former KL Dachau personnel, followed by a trial of 61 from Mauthausen (known as the “Altfuldisch trial”), then 45 from Flossenbürg. Although he was on the verge of nervous exhaustion, Denson agreed to prosecute the Buchenwald accused.

Representing the Buchenwald accused as defense counsel were Major Carl Whitney and Captain Emanuel Lewis. Like all the tribunal defense attorneys appointed to defend their clients, they had the impossible task of proving that their clients, accused of participating in some of the most heinous acts imaginable, were innocent or, at the very least, should be shown leniency by the court.

The Trial of Ilsa Koch

The trial of the Buchenwald accused included gruesome evidence—a shrunken head, pieces of tattooed human skin, etc. There was a parade of former inmates on the witness stand who delivered damning testimony about the abuses they saw, heard about, and experienced first-hand that connected the accused to crimes. Lewis and Whitney did their best to poke holes in the testimony, but theirs was a losing battle.

The part of the tribunal that packed the courtroom with reporters and observers was, not surprisingly, Ilse Koch’s testimony, for everyone wanted to see and hear the woman whose name had been associated with such horrific crimes.

Several months pregnant after a sexual liaison with a fellow prisonerat Dachau, she coolly deflected every attempt by Denson to place her at the center of the prisoner abuses. She adamantly claimed to know nothing about what her husband and the other SS personnel at the camp might have done to the inmates, had never instructed anyone to hurt or humiliate any prisoner, and had never requested that any prisoners with tattoos be killed.

She was, as she tried to convince the court, nothing more than an innocent wife and mother whose sole duty in life was to look after her little children 24 hours a day, seven days a week. She was innocent of all charges.

In the end, however, the testimony of former inmates was just too overwhelming and she, along with the other 30 accused, were found guilty in August 1947. Many were sentenced to death, and a few even executed, but Ilse was given a life sentence.

On October 29, 1947, Ilse Koch gave birth in prison to a son she named Uwe, who was turned over to a German child-welfare agency and raised in an orphanage.

In the late 1940s, relations between the Western powers and the Soviet Union worsened. The West was eager to enlist West Germany in the bulwark against the growing influence of communism. Lt. Gen. Lucius Clay, military governor of Allied-occupied West Germany and commander of all U.S. forces in Europe, was tasked with trying to contain the advances of the Soviets short of going to all-out nuclear war.

Clay was also the reviewing authority of all the German war-crimes trials and he was presented with a petition for clemency that said that there was insufficient proof that Ilse Koch had played any role in the operation of Buchenwald or in the alleged selection and execution of tattooed prisoners. The petition called for the reduction of her life sentence to four years, including time served.

In September 1948, General Clay announced the reduction of Ilse Koch’s sentence and 11 months later she was released from American custody. Almost immediately, she was re-arrested by West German authorities and jailed in Augsburg. She was tried again, this time for crimes against German citizens while she was living at Buchenwald. On January 15, 1951, she was once more pronounced guilty and sentenced to life at the women’s prison in Aichach, Germany. A later appeal failed to overturn the Augsburg verdict.

In 1966, 19-year-old Uwe Köhler (Ilse’s maiden name) began showing up at the prison for weekly visits but on September 2, 1967, he was told that she had hung herself in her cell that morning.

Twenty-eight years later, on April 23, 1995, Andrew Rosner, a survivor of the Buchenwald subcamp at Ohrdruf, said to the assembled veterans of the 89th Infantry Division in a ceremony in Wichita, Kansas: “There are those who would tell you World War II veterans of the 89th Division that what you saw at Ohrdruf and at other camps never happened the way you said it did. But—we were there. I, the victim. You, the liberators. I, the survivor. You, the witnesses. And together we must, in our golden years on this earth, again do battle with the forces of man’s worst evil so that what I saw and you lived through almost 50 years ago—what we saw—will not be tossed aside as insignificant in the annals of man’s history. It must be made so important that no one can ever say it didn’t happen that way, and therefore they could be allowed to repeat it.

The camp atop the Ettersberg did not disappear following its liberation. Located on the east side of the “Iron Curtain,” the Soviet government turned the camp into a ready-made place for the incarceration, from 1945 to 1950, “of persons who had served the National Socialist regime in an official capacity,” but also included victims of arbitrary arrest.

In September 1958, the National Buchenwald Memorial (Nationale Mahn-und Gedenkstätte Buchenwald) was established under the auspices of the East German government. A monumental complex, designed and built by the East Germans, has been established near the entrance to the camp.

Sadly, the lessons of the Holocaust seem to have largely been forgotten. Perhaps, by bringing to light the details of such horrendous examples of “man’s inhumanity to man” as perpetrated at Buchenwald and elsewhere, the world can begin to understand how such terrible things can happen and do everything possible––to include pre-emptive war––to ensure that they will not happen again.

This article was adapted from The Beasts of Buchenwald Trilogy and Buchenwald: Hell on a Hilltop by Flint Whitlock, editor of WWII Quarterly.

She deserved the death sentence, pure and simple.