By Victor Kamenir

By January 1967, the buildup of Communist forces in the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) convinced Gen. William Westmoreland that a large-scale incursion by North Vietnam’s People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) was only a matter of time. As the commander of the Military Assistance Command—Vietnam (MAC-V), Westmoreland found himself critically short of available combat formations to bolster defenses of northern provinces in the I Corps Tactical Zone south of the DMZ.

The two-division III Marine Expeditionary Force (MEF) responsible for the I Corps had its hands full and Westmoreland tasked his chief of staff, Maj. Gen. William Rosson, with creating plans for a provisional three-brigade Army task force. Rosson, who grew up in Oregon and graduated from the University of Oregon, designated the new formation Task Force Oregon, after his home state. A World War II veteran, Rosson was an old hand in Vietnam, having served with the French forces as part of the U.S. Military Advisory Group-Indochina in 1954.

Rosson earmarked three infantry brigades for the task force—the 196th (Light), 198th and 11th. Additional artillery, aviation, and engineer assets would provide Task Force Oregon with the capabilities of a full infantry division. Since the 198th and the 11th were newly activated units still in training in the U.S., the 1st Brigade (101st Airborne Division), and the 3rd Brigade (25th Infantry Division) would serve in their place until they got to Vietnam. Frequently acting as a fire brigade, the 1st Brigade (101st AD) had earned the nickname, “The Nomads of Vietnam.” Until the task force activated, The stand-in brigades would continue with their normal assignments until the task force was activated.

Enemy pressure in the I Corps Tactical Zone came from two directions. In the North, Communists could launch conventional offensives across the DMZ. While from the west, the enemy attacks came from camps in Laos and the mountainous interior, with a scant Allied presence other than several American Special Forces camps.

Increasing Viet Cong and PAVN attacks immediately south of the DMZ prompted Westmoreland to issue orders on April 12, 1967, for the 3rd Brigade (25th ID) to go to Duc Pho, a district capital in the Quang Ngai Province, two miles inland from the South China Sea. At the same time, Westmoreland redeployed the 196th Infantry Brigade to Chu Lai Marine Corps Air Base in the Quang Ngai Province, 40 miles up the coast from Duc Pho. Elements from the 196th Infantry Brigade established Landing Zone Baldy at the intersection of Highway 1 and Route 535, some 20 miles northwest of Chu Lai. Soon expanded, LZ Baldy was redesignated as a Fire Support Base, a major combat and logistics hub.

On April 20, Westmoreland activated Task Force Oregon at Chu Lai under Rosson’s command, under III MEF’s operational control.

The arrival of the Army task force freed Marine ground units to shift north closer to DMZ, leaving Marine Aircraft Group 12, equipped with A-4 Skyhawks, and Marine Aircraft Group 13, with F-4 Phantom IIs, to operate from Chu Lai. Elements of the South Korean 2nd Marine Brigade and the Army of the Republic of Vietnam’s (ARVN) 2nd Division filled the gap between the two U.S. Army bases.

The base at Chu Lai rapidly expanded to a sprawling complex alongside sandy beaches framed by palm trees. The idyllic scene greeting soldiers newly arriving in Vietnam was interrupted by outgoing artillery and the roar of Marine jets taking off from the airfield. After a few days of training at the Combat Center, the replacements were assigned to their new units and thrust into the brutal reality of jungle warfare.

The coastal provinces in the I Corps Tactical Zone—the region nearest North Vietnam and adjacent to the DMZ—had been under almost total Communist control since the First Indochina War in the 1950s. Except for the American base at Chu Lai, the enemy controlled most of the coastline of the two provinces, bringing in supplies and weapons by boat from North Vietnam.

At the heart of the area, straddling the Quang Tin and Quang Ngai Provinces and extending 25 miles inland, is the Que Son Valley. From its mountainous western end to the coastal lowlands, rice farmers eked out a living in villages and hamlets on low hillocks among rice fields crisscrossed by thick hedgerows. Two roads, Route 535 and Route 534, ran west from coastal Highway 1, joining at the district center of Hiep Duc at the valley’s west end.

The local Viet Cong forces and the PAVN 2nd Division used the valley as a logistical area and base of operations. Senior Col. Le Huu Tru commanded the 6,000-strong veteran PAVN division, composed of the 3rd, 21st, and 31st Regiments, with anti-aircraft assets, 120mm rockets, and mortars. The constant clashes between allied and Communist forces were described by a journalist as, “beyond the coastal highways, the [Americans] are interlopers, fighting a frustrating, dirty war against an enemy they rarely see.”

Rather than fight conventional battles, the PAVAN/VC tactic was to infiltrate an area, establish defensive positions, then ambush the Americans—inflicting as many casualties as possible before withdrawing.

Arriving Army battalions took over from the Marines the task of locating enemy bases and supply caches in an inhospitable terrain full of mines, booby-traps and snipers. Success was measured in body counts and captured enemy weapons and equipment. Rosson immediately launched a series of aggressive operations in conjunction with the South Vietnamese and South Koreans, named after eastern Oregon counties: Malheur, Hood River, Benton, and Cook.

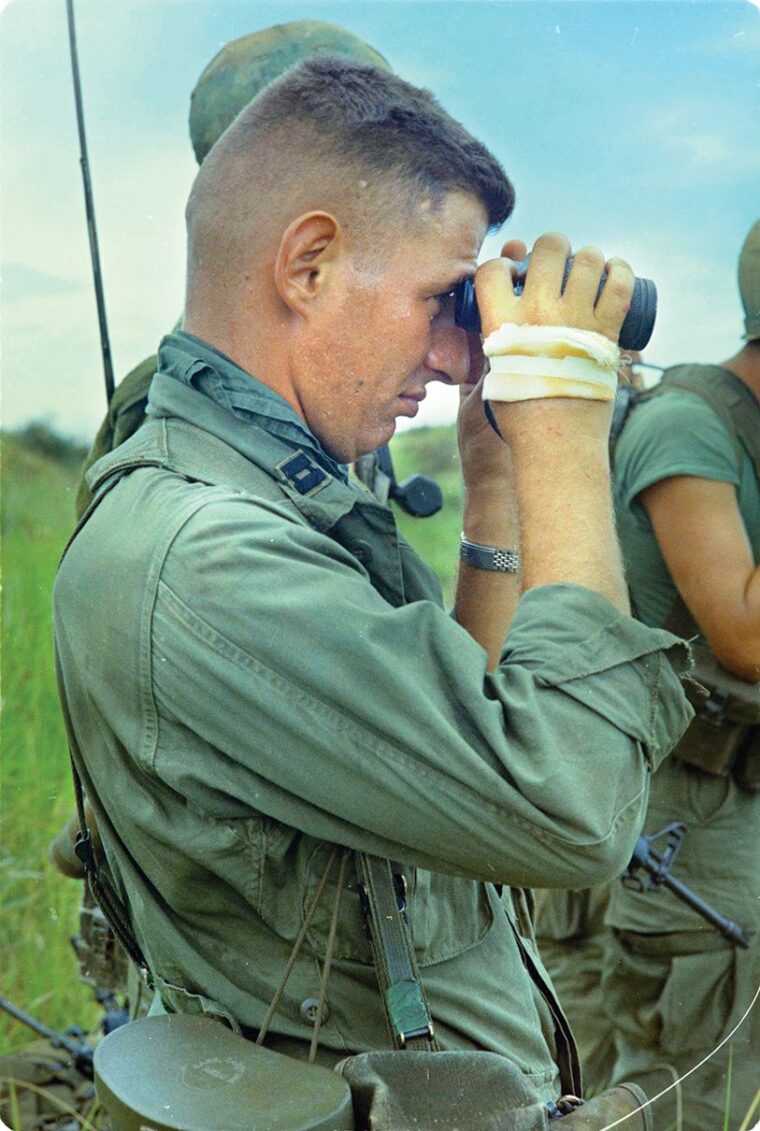

In the field, U.S. infantry companies typically operated within a two-hour march apart for mutual support. Individual platoons had their own objectives within a company’s area of operations, but stayed close to reassemble rapidly if needed. Troops carried rations and ammo for three to five days because they might be in the field for extended periods and supplies dropped by helicopter could give away their position.

At first, the Army brigades had success as the North Vietnamese, used to Marines with few helicopter assets, were accustomed to moving around even during the day without being observed. The U.S. Army’s ubiquitous UH-1 Iroquois “Huey” gunships exacted a heavy toll on the Communist troops before they adjusted their tactics and operations. The PAVN quickly developed effective countermeasures, utilizing heavy 12.7mm and 14.5mm machine guns in the anti-aircraft role.

The enemy was everywhere and nowhere in the hostile and alien terrain. A GI might come across a statue of Buddha sitting serenely in a clearing—never hearing the sniper’s shot, or worse, hearing the sickening “click” of an activating booby trap. The Viet Cong were careful to mark mines and traps so their troops and local villagers would not walk into them. Allied patrols tried to get cooperation from villagers before sweeping an area, but it was rarely possible, as they might be Viet Cong sympathizers or too terrified to cooperate.

In a typical operation, U.S. infantry inserted by helicopter would surround a hamlet or a village and sweep it for Viet Cong cadres and sympathizers, weapons, and supplies while armored vehicles set up blocking positions to prevent escape. Villagers were then allowed to take what they could carry and moved to refugee camps. Then the village was burned, becoming a free-fire zone where U.S. firepower could be brought to bear without fear of killing civilians.

The 1st Brigade (101st AD), arrived at Duc Pho in May and immediately began patrolling west of the town. On May 15, a company of paratroopers was ambushed by an estimated battalion-size force of PAVN regulars fortified in a bunker complex. Maj. Charles Kettles, a flight commander in the 176th Aviation Company, 14th Combat Aviation Battalion, volunteered to lead a flight of Hueys to bring in reinforcements and evacuate the wounded.

Kettles twice led flights to the landing zone, where heavy enemy fire hit soldiers before they had a chance to leap out of the helicopters. In the afternoon, a call came in to evacuate the remaining 40 infantrymen, as well as four crewmembers from a shot-down helicopter from Kettles’ company. Kettles led the choppers back to the fight for the third time that day, the soldiers scrambling aboard as machine guns peppered the helicopters. On the return leg, Kettles was advised that eight men had been left behind, cut off by heavy fire. Without a thought, Kettles flew back and rescued the missing soldiers, his damaged helicopter barely making it back to base. For his actions, Major Kettles received a Distinguished Service Cross in 1968 and a Medal of Honor in 2016 after a special act of Congress. “We got the forty-four out. None of those names appear on the wall in Washington. There’s nothing more important than that,” Kettles said.

In July 1967, Rosson was promoted to lieutenant general and took command of the 1st Field Force, a corps-level formation. Task Force Oregon was turned over to Brig. Gen. Samuel Koster, a veteran of World War II and Korea.

By the end of August 1967, the 1st Squadron, 1st Cavalry Regiment, 1st-1st Cavalry, composed of three armored cavalry troops equipped with M113 Armored Cavalry Assault Vehicles, finished deploying to Vietnam and joined Task Force Oregon.

On September 11, Koster commenced “Operation Wheeler,” named for another Oregon county, in the southern part of the Que Son Valley. Under the command of Brig. Gen. Salve Matheson, 1st Brigade (101st AD) established their headquarters near Tam Ky, the capital of Quang Tin Province, on Highway 1. The goal of Operation Wheeler was to conduct a series of search-and-destroy missions against the 2nd PAVN Division, which has been operating in the area since 1966.

On September 25, 1967, Westmoreland issued orders converting Task Force Oregon, a division in all but name, to an actual numbered division, the 23rd, the seventh U.S. division fighting in Vietnam. At the same time, Koster received his second star, and the 3rd Brigade, 25th Infantry Division, was redesignated as the 3rd Brigade, 4th Infantry Division. In addition, Westmoreland temporarily shifted the 3rd Brigade, 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) under Col. Hubert Campbell in early October north from the II Corps to assist with Operation Wheeler.

First activated in May 1942 on the Pacific island of New Caledonia, the 23rd Infantry Division became known as “Americal” (American, New Caledonian Division), even in official correspondence.

Arriving in the I Corps Tactical Zone, the 3rd Brigade (1st Cav) established Landing Zones Leslie and Ross on the west end of the Que Son Valley by the village that gave the valley its name.

On October 3, Campbell’s Brigade launched “Operation Wallowa” (another Oregon county) from Landing Zone Baldy to form the northern prong of Operation Wheeler. At the same time, Koster reinforced Matheson with a battalion from the 3rd Brigade, 4th Infantry Division.

On October 22, leading elements from the 198th Infantry Brigade under Col. Louis Gelling began arriving at Duc Pho from Ft. Hood, Texas.

On November 8, the 3rd Regiment (2nd PAVN) sprung an ambush with 75mm recoilless rifles on a column of tracked armored vehicles from the 1st Cavalry Division near LZ Ross. The ambush cost the lives of 10 American soldiers, with 46 wounded. In response, artillery and air strikes pulverized the area. The infantry companies inserted the following day found three 75mm recoilless rifles and forty-five enemy bodies. A captured soldier disclosed that the 68th PAVN Artillery Regiment, armed with 122mm rockets, was in the area.

Unable to employ conventional artillery in the mountainous wooded terrain, Communist forces extensively utilized Soviet and Chinese-made 105-pound portable rockets, frequently fired from improvised bamboo launchers up to seven miles away.

Koster ran extensive helicopter hunter-killer operations to find and destroy Vietnamese rockets. Aero-scout White Teams attempted to locate enemy positions and call them in for aero-weapons Red Teams to pounce upon. When the two teams operated in tandem, they were called Pink Teams. Afterwards, a flight of four troop helicopters, each carrying a Blue Team–a six-man infantry aero-rifle unit—was inserted to conduct mop-up operations and evaluate the effects of an attack.

These missions flew so low and close that the Americans aboard helicopters and the Communist soldiers on the ground could see each other’s eyes. On multiple occasions, the choppers returned to base with enemy blood on the outside of their windshields.

On November 11, to facilitate command and control, Koster merged operations Wheeler and Wallowa into one, conducted primarily by the 1st Brigade (101st AD) and the 3rd Brigade (1st CD).

On November 13, automatic weapons fire shot down a Blue Team Huey. As additional U.S. helicopters arrived to rescue the downed aircrew, several concealed enemy 12.7mm machine guns unleashed a fury of fire. One chopper exploded in the air, and two more crash-landed. In response, American artillery and aircraft pounded the reported enemy positions. Then three rifle companies from Lt. Col. Robert Kimmel’s 1st-35th Infantry established a defensive perimeter around the downed aircraft.

Kimmel was up the next day in bad weather directing the search-and-destroy operation from a command-and-control helicopter when it was hit by enemy machine gun fire and crash landed in a rice paddy. Another aircraft picked Kimmel up, and he was back in the air an hour later. Kimmel returned the next day when inclement weather forced the pilot to fly low to the ground. After enemy 12.7mm rounds peppered the chopper, it lost its tail rotor and exploded on impact, killing all aboard. Lt. Col. Marion Ross and his 2nd-12th Cavalry took over the mission. After failing to establish contact with the elusive enemy for two days, Ross terminated the operation. In the wake of the incident, the Americal Division command changed tactics by requiring ground units to secure the area before attempting rescue by helicopter.

After additional in-country training, the 198th Infantry Brigade moved from Duc Pho to Chu Lai to relieve the 196th, which shifted to the southern sector of the Wheeler/Wallowa operation. The 1st Brigade (101st AD) temporarily moved south to II Corps Tactical Zone.

On November 22, a U.S. signals intelligence detachment intercepted transmissions that appeared to come from the headquarters of the 3rd PAVN. Triangulation pinpointed the suspected headquarters to Hill 63, a small hill four miles east of LZ Ross.

At the time, Major Gilbert Dorland, the executive officer of the 4-31st Infantry Regiment, 196th Infantry Brigade, led a mixed infantry-armor patrol in the area. The 29-year-old West Point graduate, on his second Vietnam tour, led two companies from his battalion, two platoons of armored personnel carriers from Troop F, 17th Cavalry, and four tanks from Troop A, 1-1st Cav. It was too late in the day to act on this intelligence, and Dorland’s small task force went into a nighttime laager.

The following day, under heavy rain, Dorland’s two infantry companies approached Hill 63 from two directions, with the armored vehicles in reserve. As the U.S. soldiers began moving uphill around 7 a.m., a withering hail of small arms and machine-gun fire struck one of the companies. In minutes, four Americans were dead and eight wounded. The second company moved up and became heavily engaged as well. Judging by the fire intensity, Dorland estimated the enemy numbers to be roughly battalion-strength.

At Dorland’s command, M48 tanks and M113 armored personnel carriers charged forward to support the infantrymen. The armored vehicles advanced so fast that Dorland remembered some PAVN scrambling out of their spider holes practically from under the vehicles’ tracks.

Enemy recoilless rifles opened fire from short range, scoring hits on two tracked vehicles. Dorland, riding on top of his APC, was thrown off when a hit on his vehicle killed the track commander. Not seeing Dorland on the ground, the driver backed over the major as he maneuvered to shield infantrymen behind the vehicle. Although seriously hurt, Dorland was still able to move. He refused medical care and evacuation and remained in the field to direct the fight.

With the weather clearing, Dorland called in artillery and air strikes on enemy positions. Marine F-4 Phantoms from Chu Lai pounded the area with napalm and 500-pound bombs. Despite Americans’ overwhelming firepower, the PAVN soldiers refused to surrender or withdraw from their well-fortified positions. The M48 Patton tanks blasted enemy bunkers at point-blank range and crushed the spider holes with their tracks while infantrymen got in close to drop grenades and C-4 into tunnels.

Aware of the brutal fight on Dorland’s hands, the 196th Brigade dispatched two more infantry companies, delivered by helicopters from the 14th Combat Aviation Battalion. Despite Dorland’s reluctance to leave the fight, he was ordered to do so and was replaced by LTC Thomas, commander of the 4-31st Infantry.

When the enemy finally withdrew the following day, U.S. soldiers found 128 bodies identified by captured documents as belonging to the 2nd Battalion, 3rd PAVN Regiment. American casualties were 7 dead and 84 wounded in the fight for Hill 63. Major Dorland received the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions.

In the afternoon on December 5, U.S. observation helicopters spotted enemy soldiers between two mountaintops north of LZ Ross. Responding gunships attacked the group with devastating results. A rapidly inserted Blue Team killed several more, bringing the total to 17 enemy KIA. Among the North Vietnamese killed were the 2nd PAVN Division commander, Colonel Tru; the Division’s political commissar Nguyen Minh Duc; deputy chief of staff; chief of rear services; chief of operations and intelligence, chief of combat operations and training; and commanders of the 31st and 21st Regiments, as well as several battalion commanders.

Documents found on officers’ bodies showed plans for a division-sized attack against Ross. Based on captured documents, American intelligence believed the attack would occur around the end of December.

After the American troops withdrew from the scene of the attack, the 2nd PAVN Division’s Deputy Political Commissar Bui Duc Tung led a small patrol to recover the bodies. “When Nguyen Chon [Commander of the 1st Regiment] and I went uphill from Son Phuc, the enemy has withdrawn,” Tung remembered. “The scene was desolate, the trees were ruined, the bodies of comrades were no longer intact. I assigned soldiers to bury each person at the foot of the mountain, and local people volunteered to protect the graves.” After the war, Colonel Tru’s body was recovered and identified by his silver tooth.

On December 9, White Team helicopters located a large body of PAVN troops three miles north of LZ Baldy. Gunships and artillery blanketed the area as companies from the 1st-35th Infantry hurried to engage on the ground. The day-long fight resulted in more than 120 enemy dead and 10 taken prisoner. Interrogated prisoners revealed efforts by the 2nd PAVN Division to accumulate food stores to sustain significant operations in the Que Son Valley.

In mid-December, in the south of the I Corps, the 198th Infantry Brigade launched “Operation Muscatine” to secure the immediate vicinity of Chu Lai within the larger scope of Operation Wheeler/Wallowa.

On December 20, the 11th Infantry Brigade under Brig. Gen. Andrew Lipscomb arrived in Duc Pho from Schofield Barracks, Hawaii, and immediately began in-country training. Once deemed ready, the 11th Infantry Brigade took over the mission of Operation Muscatine from the 198th.

As a prelude to the Tet Offensive, Senior Colonel Giap Van Cuong, a new commander of the 2nd PAVN Division, received orders to destroy the 3rd Brigade (1st CD). On December 26, three North Vietnamese defectors reported an imminent attack against LZs Ross and Baldy. On January 1, 1968, all radio traffic by the 2nd PAVN Division stopped, typical of previous enemy operational patterns.

On January 2, General Koster launched a preemptive sweep near LZ Ross. A company from the 2nd-12th Cavalry rapidly established contact with the enemy west of the landing zone. Reinforced by another company, the cavalry troopers accounted for over 20 enemy KIA. Two enemy prisoners revealed the arrival of additional reinforcements, anti-aircraft machine guns, and a battery of six 122mm rocket launchers.

Before dawn on January 3, battalion-size units from the 2nd PAVN Division attacked U.S. firebases in the Que Son Valley. Landing Zones Ross and Leslie bore the brunt of the assault, coming under 82mm and 120mm mortar fire, 122mm rockets, and 75mm recoilless rifles.

Two battalions from the 3rd Regiment attacked LZ Ross from the west, while one battalion from the 21st Regiment came from the south. A sheet of fire sliced into the enemy as U.S. artillerymen lowered the gun barrels to fire practically in the faces of the oncoming PAVN troops. At LZ Leslie, an enemy company-size sapper element armed with satchel charges and flamethrowers breached the perimeter before being wiped out. By 6 a.m., the enemy fell back at the cost of 18 American dead, 137 wounded, and more than 300 North Vietnamese killed.

Throughout January 4 and 5, infantry companies from the 196th Infantry Brigade became hotly engaged with elements of the 1st PAVN Regiment in the vicinity of LZ West, six miles south of LZ Ross. As Company C (2nd-1st Infantry) was preparing night laager positions, it came under a heavy attack that killed the company commander and one of the platoon leaders. By the time another company arrived four hours later to drive the enemy back, 16 Americans lay dead, with 56 wounded. During the week’s fighting, enemy heavy machine guns in an antiaircraft role damaged thirty-two American helicopters, destroying six.

The official newspaper of the North Vietnamese Army claimed victory over one of the battalions of the 196th Infantry Brigade. “When the enemy arrived at the battle area, our two 12.7mm weapons lowered their barrels and fired at the U.S. infantry forces. The Regiment’s strong firepower subdued the enemy artillery,” the newspaper described the actions of the 3rd Regiment, 2nd PAVN Division. “Along with cover fire, the regiment formed many prongs of attack of the enemy, cutting off the rear area, and attacked the enemy’s flank, cutting the enemy forces into small clusters in order to destroy them,” the Communist narrative went, “the battle quickly resulted in victory. The 3rd Battalion, 196th U.S. Brigade, was basically put out of action. Two Companies were destroyed, and one company suffered heavy losses.”

In mid-January, the 2nd PAVN Division withdrew, having failed in its mission to destroy the 3rd Brigade (1st CD) and losing more than 1,100 men killed and about the same number wounded.

In the southern sector of the Americal Division’s area of operations, in the heavily populated Quang Tin and Quang Ngai provinces, more troops were needed to defend all population centers. Rural mountain areas were largely ceded to the enemy. Strong local Viet Cong forces controlled most of the Quang Ngai Province and fortified every hamlet and village under its control with formidable multi-layered defenses. The enemy presence was particularly heavy in the Batangan Peninsula. Two battalions from the 198th Infantry Brigade began patrolling the peninsula, relieving the South Korean Marines who moved to the Quang Nam Province.

The PAVN’s 3rd Division maintained a heavy presence in the Quang Ngai Province, where the 196th Infantry Brigade and the 3rd Brigade(4th ID) conducted sweeping operations along the Quang Tin-Quang Ngai boundary. With help from South Vietnamese forces, most population centers were relatively secured by the end of November, and the 3rd PAVN Division withdrew south to the II Corps Tactical Zone.

Without slowing down the operations tempo, General Koster shuffled the units under his command, sending the 196th Infantry Brigade to the North and replacing it with the 11th Infantry Brigade.

By the end of January, clashes with Communist forces steadily escalated, with both American brigades conducting constant battalion-sized operations. Heavy fighting and overwhelming American firepower reduced many villages to ashes, exacerbating the severe refugee problem.

When a major Communist offensive kicked off on January 31, at the start of Tet, the Vietnamese Lunar New Year, base camps of the Americal Division came under attack. An intense rocket and mortar attack hit Chu Lai Air Base. An unfortunate hit on a bomb storage facility caused a catastrophic explosion, destroying three aircraft and damaging twenty-three others. Once their bases were secured, Westmoreland moved the 3rd Brigade (1st CD) and the 1st Brigade (101st AB) to Hue to assist the Marines fighting to liberate the ancient Vietnamese Imperial Capital. In the fighting west of the city, the 2nd-12th Cavalry suffered heavy casualties.

After the Tet offensive was defeated, Westmoreland withdrew the 3rd Brigade (4th ID) from the Que Son Valley, shifting it south to Binh Dinh Province by the end of February. This left only the 196th Infantry Brigade to continue Operation Wheeler/Wallowa in the North of the I Corps. At the same time, a fourth rifle company was formed in each battalion of the 196th and 198th Brigades.

The fighting continued unabated. In the Que Son Valley, the 196th Infantry Brigade and the 1st-1st Cavalry continued searching for the 2nd PAVN Division. On February 26, the 1st-1st Cavalry, sweeping through the area two miles southwest of Tam Ky, made contact with a large force of local and Main Force Viet Cong units. Over the next three days, cavalry troopers, reinforced by an infantry company, killed more than 200 Viet Cong guerillas.

In early March, intelligence reported that elements of the Communist Division came down from the mountains to gather provisions. On March 4, the 196th Infantry Brigade and the 1st-1st Cavalry encountered a large force from the 3rd PAVN regiment. Over the next week, in a series of running firefights, U.S. soldiers killed 400 North Vietnamese soldiers.

On March 16, Company C, 1st-20th Infantry, 11th Infantry Brigade was on a sweep south of the Batangan Peninsula, an area under almost complete Viet Cong control for most of the war. Despite encountering no enemy presence or resistance in the hamlet of My Lai, American troops massacred between 350 and 500 unarmed Vietnamese civilians, ranging in age from infants to the elderly. Although aware of the event, General Koster made little effort to thoroughly investigate the tragedy, which remained unknown to the American public for another year.

From April to November 1968, when Operation Wheeler/Wallowa ran its course, the Americal Division conducted several smaller scope operations under the Wheeler/Wallow aegis. From April 8-19, the 11th Infantry Brigade conducted Operation Norfolk Victory, a series of area sweeps in the Nghia Hanh District, Quang Ngai Province, resulting in forty-three enemy and five Americans killed.

The 198th Infantry Brigade carried out Operation Burlington Trail in the Quang Nam Province to keep Route 533 open in the Que Son Valley. By the time Burlington Trail ran its course in December, Communist losses came to over 1,900 killed at the cost of 129 American lives.

In June, having served a year in command, Koster returned to the United States and Maj. Gen. Charles Gettys became the second commander of the Americal Division on June 23.

During most of July, Gettys conducted Operation Pocahontas to secure the west end of the Que Son Valley with a provisional task force of five U.S. infantry battalions and supporting South Vietnamese units. Despite extensive patrolling and sweeps, the operation only killed 127 enemy troops while losing 18 U.S. soldiers.

Elements from the 3rd PAVN Division, from the Binh Dinh Province in the II Corps Tactical Zone, were active in the southern Quang Ngai Province. In September, the 11th Infantry Brigade conducted Operation Champaign Grove against the 3rd PAVN Division, inflicting 378 enemy KIA while losing 41 Americans. The Brigade then shifted into Operation Vernon Lake in November, the last action under the Wheeler/Wallowa umbrella, eliminating 435 enemy soldiers and losing 35 of their own.

On November 16, just five days after terminating Operation Wheeler/Wallowa, Maj. Gen. Gettys flew to inspect a captured PAVN base camp. On board the general’s UH-1 helicopter was the Division’s Assistant Chief of Staff, Maj. Colin Powell, future Chairman of Joint Chiefs of Staff. During landing, the chopper’s rotor blade struck a tree, causing the machine to drop from the height of three stories. Despite suffering a broken ankle, Powell pulled the injured Getty and two other officers from the wreckage while a door gunner rescued other occupants. Because the crash was not a result of enemy action, Power received a Soldier’s Medal, an award for bravery not involved in actual combat contact with the enemy.

Despite the ultimate sacrifice made by more than 220 American servicemen and more than 10,000 claimed PAVN and Viet Cong killed, Operation Wheeler/Wallowa ultimately failed to gain control of the three southern provinces in the I Corps Tactical Zone. While the Communists scored a significant propaganda victory during the Tet Offensive, their forces suffered grievous losses in men and materiel. No longer able to engage the Americans in the “battle of big battalions,” the PAVN and Viet Cong forces continued the guerilla warfare unabated.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments