By William E. Welsh

An event of great significance in early medieval Europe occurred in 753, when newly ensconced Pope Stephen II decided to journey north to Metz to confer with Frankish King Pepin III (known as “The Short”). Although previous popes had traveled east, none had ever journeyed into what the Italians regarded as the hinterlands of northern Gaul.

The reason for the pope’s journey was the dire threat that the Lombards posed to Rome. At the urging of Byzantine Emperor Constantine V, Stephen had first gone to Pavia to reason in person with Lombard King Aistulf regarding his aggressive moves against Rome, as well as his conquests in the Byzantine exarchate of Ravenna.

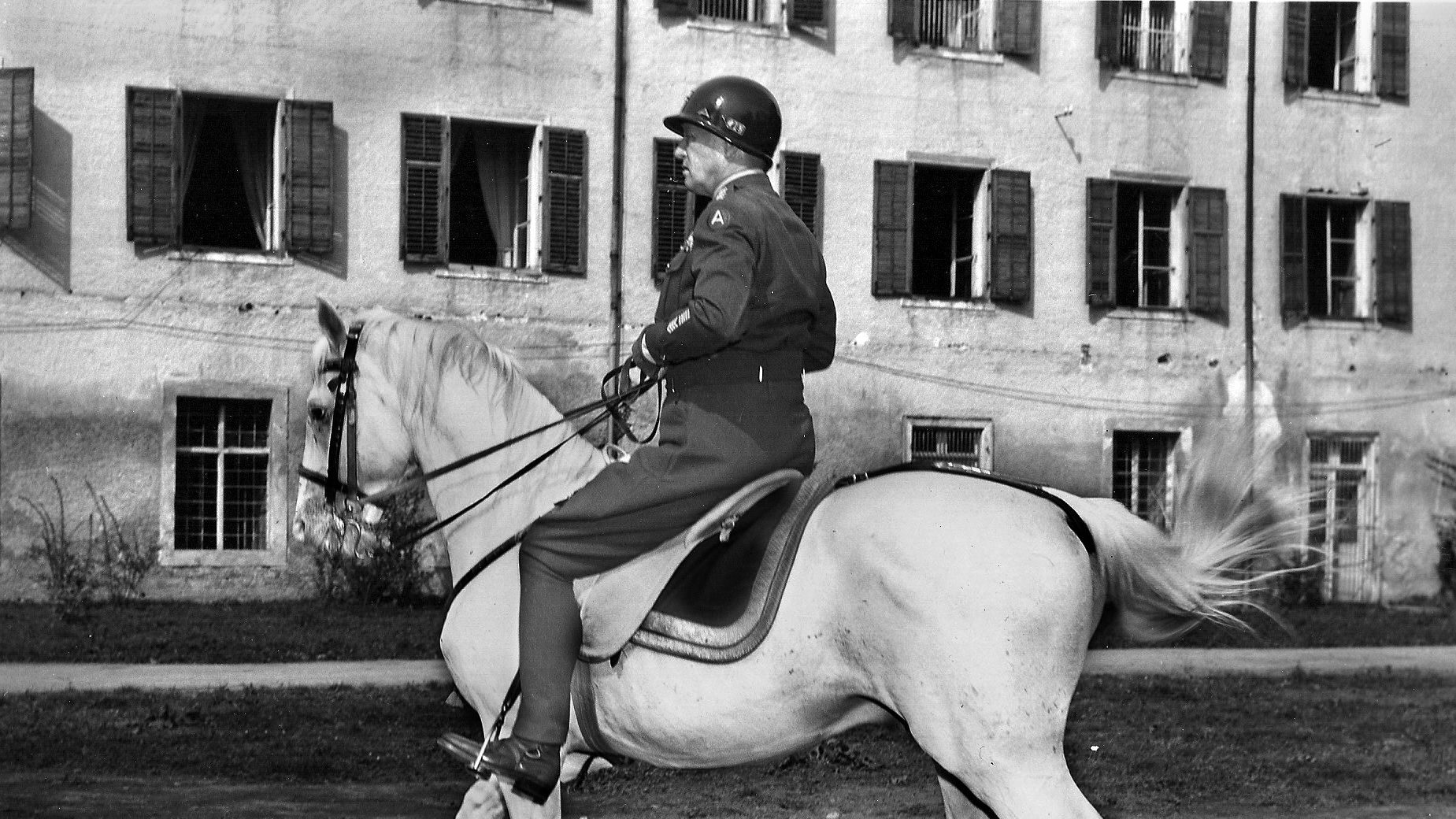

After reaching an impasse, the pope and his curia then set out for Francia. They crossed the Great Bernard Pass through the Alps, arriving before the onset of winter at St. Maurice-in-Valais. Pippin’s eldest son, Charles, who would one day become Charlemagne, met them there, and he escorted the pope to Ponthion. Arriving at this destination on January 6, 754, the pope began a series of productive meetings with Pepin.

The Salian Franks had won control of nearly all of Gaul in the early 6th century under the leadership of the third ruler of the Merovingian Dynasty, King Clovis, who succeeded in driving the Visigoths from most of southern Gaul, except for Septimania. His conversion to Catholic Christianity at a time when most of the Germanic rulers were nontrinitarian Arian Christians greatly enhanced his reputation among the elites of Southern Europe. By the late 7th century, however, the Merovingian kings were bankrupt and bereft of royal estates. In contrast to the kings, the mayors of the palace had increased their power substantially, and they had become the de facto rulers of the expansive Frankish realm. The mayor of the palace was the top official in the Merovingian royal court; as such, he supervised dukes and counts, presided over the royal court, and commanded the Frankish army.

Mayor of the Palace Charles Martel had fought tirelessly during his lifetime to broaden his authority over Austrasia, as well as the adjoining regions of Neustria, Burgundy, and Aquitaine. The Frankish kings were puppets, and he was the de facto monarch. Indeed, he ruled Francia for many years with no king on the throne at all. Charles won lasting fame for defeating Muslim raiders at Poitiers in 732. In honor of his triumph at Poitiers, Charles received the sobriquet “The Hammer.”

Before his death, Charles the Hammer drew up plans to divide his realm among his three sons. His two older sons, Pepin and Carloman, though, decided to disinherit their half-brother Grifo, who was still in his minority—so they locked him away in a monastery. Pepin became the mayor of the palace for Neustria, Aquitaine, and Provence, and Carloman held the same position for Austrasia, Thuringia, and Alemannia. The two brothers ruled during a three-year interregnum, eventually installing a monk on the throne who shared blood with previous Merovingian kings. This individual, who became King Childeric III, was nothing more than a figurehead, as usual.

The two brothers endured constant warfare to maintain the hard-won military and political gains of their father. Rebellions erupted in the duchies on the perimeter of Francia almost immediately on their ascension to power. The dukes of Aquitaine, Bavaria, and Alemannia terminated the agreements which they had made with Charles the Hammer during his reign and forged an alliance against the Frankish brothers. To tamp down the rebellions, Pepin and Carloman conducted both solo and joint campaigns to vanquish the rebellious Frankish vassals.

During his quarter-century reign, Charles the Hammer had succeeded in establishing overlordship over Duke Hunoald of Aquitaine, but the duke attempted to assert his independence immediately upon Charles’ death, encouraging his warriors to rebel against the Franks. Pepin and Carloman responded swiftly to the Aquitanian revolt, sending armies to ravage northern Aquitaine in 742. The Franks captured strongholds, imprisoned garrison troops, and amassed large amounts of loot. Afterwards, Carloman invaded Alemanni territory, cornered its army on the Danube River, and forced it to surrender. He then made its leaders acknowledge him as their suzerain.

The following year, the two brothers teamed up again to wage war against the rebellious Duke Odilo of Bavaria, who fought back with an army reinforced with Alemanni, Saxon, and Slav mercenaries. In a pitched battle fought near the Lech River, the Franks inflicted a crushing defeat, after which Carloman executed his prisoners to instill fear in the vanquished Bavarians. To punish the Alemanni for assisting the Bavarians, Carloman installed two Frankish counts to administer their lands. When Duke Hunoald of Aquitaine rebelled again in 745, Pepin defeated his army and forced him to accept Frankish overlordship. Hunoald found the idea of being Pepin’s vassal too humiliating to bear and abdicated in favor of his son Waiofar.

Carloman informed Pepin the following year that he wished to retire from military life and become a monk. He departed for Italy in 747 and entered the Benedictine monastery at Monte Cassino. Carloman had requested that Pippin take his adolescent son Drogo under his wing and relinquish Austrasia to him when he reached his majority.

But with Carloman gone, Pepin began plotting to disinherit Drogo and depose Childeric so that Pepin could take the crown of Francia for himself. He realized that to successfully depose Childeric, he would need the support of both the nobility and the Catholic Church in Rome. As for Drogo, when he eventually obtained his majority and demanded his inheritance, Pepin simply locked him away in a monastery.

Pepin had second thoughts about his treatment of his half-brother, Grifo. He freed him in 747 and bestowed upon him a substantial duchy comprising 12 Frankish counties, which would serve as a border march between Neustria and Aquitaine. Grifo, however, was not inclined to serve as a subordinate official in the government of his half-brother Pepin. Setting off with a small group of Frankish followers for Eastphalia, Grifo formed an alliance with Saxon leader Theodoric, one of the many rebellious Frankish vassals.

Pepin soon marched against Grifo and Theodoric in a multi-pronged invasion of Eastphalia. To support his army’s thrust into Eastphalia from Thuringia, he arranged for his Frisian and Slavic allies to invade Eastphalia from the north. Pepin and his allies crushed Saxon opposition, while Grifo escaped to Bavaria, where he hoped to ally himself with Duke Odilo. Odilo, however, had recently died, and since Odilo’s seven-year-old son Tassilo was too young to rule, Grifo appointed himself the Bavarian regent.

Pepin faced a major crisis with the steady increase of Grifo’s power. A small number of disaffected Frankish warriors had joined Grifo in Bavaria, so Pepin invaded it for the sole purpose of driving Grifo from power. Grifo escaped again, this time to Aquitaine, but his luck finally ran out when he was assassinated.

Pepin had first approached the papacy about the matter of taking the crown of Francia for himself in 750, when he’d sent envoys to Rome to discuss the subject with Pope Zacharias. The Pope had responded favorably: “It was better to call him king who had royal power than him who did not,” observed Zacharias.

After he disposed of King Childeric, Pepin prevailed upon the Frankish nobility in 751 to elect him as their new king. Archbishop Boniface of Mainz anointed him in a coronation ceremony held at Soissons, making Pepin the first of the Carolingian kings.

At Ponthion in January 754, Pope Stephen anointed Pepin a second time and designated him and his sons as “patricians of Rome.” In return, Pepin agreed to compel the Lombard Aistulf, either by diplomacy or by force, to relinquish his conquests in the exarchate of Ravenna, which the Byzantines themselves were unable to reconquer.

Pepin was reluctant to intervene militarily in Lombardy, as he had no intention of conquering the region. He sent four delegations to try to persuade Aistulf to return the lands he had taken from the Catholic Church. He even offered Aistulf a large sum of money to withdraw from the exarchate of Ravenna. When all of Pepin’s diplomatic efforts failed, he assembled 40,000 troops for an invasion of Lombardy.

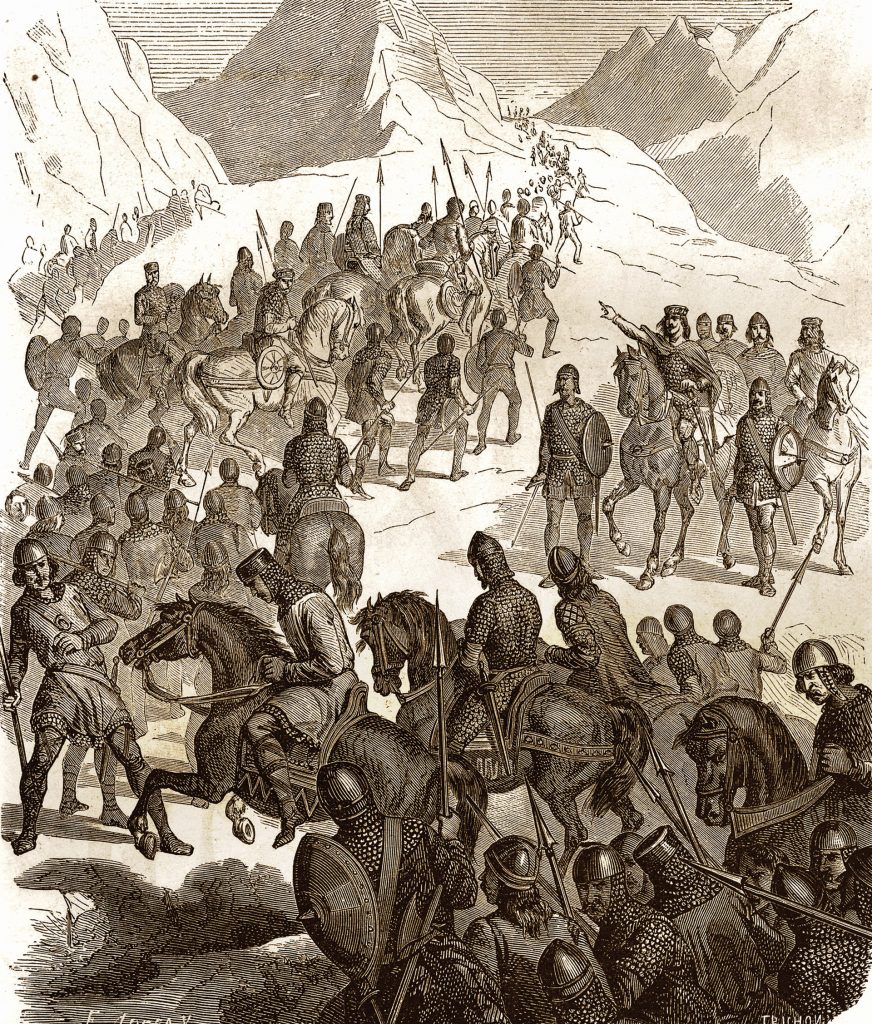

The Lombards had long ago fortified their frontier to block hostile armies from crossing the key mountain passes. When Aistulf learned of the route by which the Franks were marching, he rushed to Susa in Piedmont to block the Franks. When the Frankish host arrived, he left the protection of his fortifications and attacked Pepin’s vanguard as it marched through a defile.

The Franks formed themselves into a phalanx and repulsed the Lombard attack, nearly succeeding in killing Aistulf in the process. The Lombard king withdrew to his heavily fortified capital at Pavia. Pepin invested the town, severing its communications and supply lines with other Lombard towns. Aistulf surrendered after a short siege. As part of the surrender terms, he agreed to return the Byzantine territory that he had taken. Rather than returning these lands to Byzantium, though, Pepin gave them to the Church of Rome.

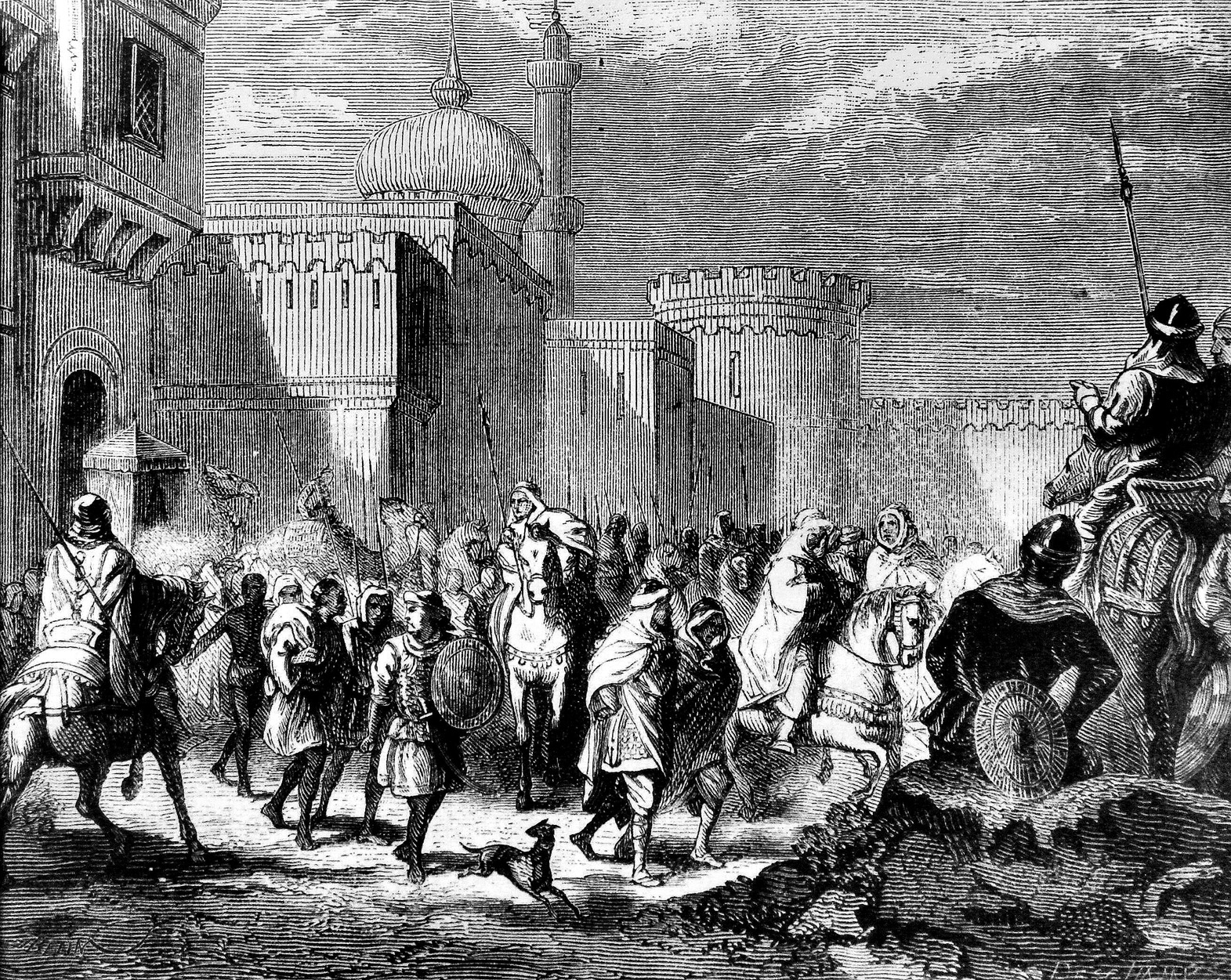

Not long after Pepin had returned home, Aistulf reneged on his pledge. In January 756, the Lombard king attempted to storm Rome, but its defenses proved too strong. He sent his soldiers to ravage papal lands in Campagna.

Pepin returned to Italy later in the year and successfully besieged both Pavia and Ravenna. Once again, Aistulf capitulated and accepted Pepin’s terms. This time, Pepin made him agree to pay a hefty tribute to the Franks. When Aistulf died later that year from a hunting accident, his successor Desiderius reneged on the treaty with the Franks. Pepin, though, believed he had performed his obligation to the papacy, and he refused to make any more expeditions to war-torn Italy.

Pepin spent the last decade of his life campaigning in Aquitaine; his goal was to integrate the duchy into Francia. One of his greatest successes occurred in 762, when he masterminded a brilliant campaign to capture the duke’s capital at Bourges. He planned a two-pronged invasion. An army from Austrasia with a lumbering siege train would approach Bourges from the east. To ensure that the Aquitanians did not attack the slow column, Pepin made a feint towards the lower Loire River with his Neustrian army to distract Duke Waiofar. The ruse worked, and the Austrasian army was able to begin investing the heavily fortified town before Waiofar figured out Pepin’s actual objective. Pepin then led his Neustrian troops to Bourges to participate in the siege. He had a total of 25,000 troops, which was the equivalent of four Roman legions.

The Franks established fortified encampments and siege walls to cut off supplies and reinforcements to the garrison. Pepin arrived at some point early in the siege to take charge of the siege operations. The Franks had developed trebuchets in the 8th century after studying their use by both Muslims and Byzantines, and employing them now, they knocked down parts of the walls of Bourges. In the third month, the Franks fought their way into the town through the breaches their siege engines had made in the walls. Although Pepin suffered significant losses, he captured the town. He permitted most of the surviving garrison troops to depart home, but he forced the Gascons, who were good soldiers, to join his army.

Waiofar decided afterwards not to fight a static defensive battle from his fortified towns, instead undertaking a war of maneuver. This strategy did not work, however, because the Frankish army was simply superior to the Aquitanian army. By 768, Pepin had fought his way to the Gironde River. He had captured numerous towns in northern Aquitaine, the most important of which were Bourbon, Clermont, Limoges, and Thouars. That same year, local troops in the pay of Pepin assassinated Waiofar in the forests of Perigord.

Pepin ruled Francia with the proverbial iron hand. His enemies found him a remorseless and determined foe. He excelled in battle tactics, siegecraft, logistics, and leadership. His victories over the rebellious dukes on the eastern and southern frontiers of Francia, as well as his conquest of Aquitaine, set the stage for his son Charlemagne’s wars of conquest in northern and central Italy, Saxony, Carinthia, and the Spanish March south of the Pyrenees. Without Pepin’s groundwork, it is unlikely that Charlemagne would have become the emperor of the Romans.