By Joshua Shepherd

Late on the evening of June 5, 1967, a flight of Sikorsky S-58 helicopters sped low above the sands of Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. Aboard the aircraft was a hand-picked force drawn from Israel’s 80th Paratroop Brigade. Among the best-trained and well-equipped men in the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), the paratroopers had been tasked with a daring night assault of heavily defended Egyptian artillery positions behind Umm Katif.

As soon as the helicopters touched down, paratroop commander Colonel Dani Matt’s men were on the move. They had succeeded in landing just two miles from the objective, and Matt was astounded that their presence remained undetected, but as the paratroopers trudged toward the enemy position, bedlam erupted. “Suddenly, the sky lit up with hundreds of illumination shells, followed by the crash of explosives as mortar fire landed on our approach route,” recalled Matt.

Despite the noisy reception, it became apparent that the paratroopers still held the initiative as the shock of the initial barrage faded. The Egyptian fire was poorly directed, and it was obvious that they were firing blind. As the emboldened Israelis rushed the last remaining yards toward their target, they found the Egyptian artillery park unprotected by minefields or barbed wire. Wildly spraying the enemy with sub-machine-gun fire, the Israelis stormed the position in a chaotic fight for control of the guns.

“Ammunition bunkers exploded into fiery infernos,” Matt wrote afterwards. “The noise became overwhelming, the smoke and dust suffocating.” For Matt and his men, the fight was a life and death struggle in the sandy wastes of Sinai. For the IDF, this operation was vital to the success of one of the largest armored attacks in the history of the Middle East and critical to victory in the Six Day War.

By the summer of 1967, the modern state of Israel laid claim to a short but bloody history. After declaring independence in spring 1948, the nascent Jewish state was invaded by a coalition of Arab nations bent on the destruction of Jewish settlements. Following a brief but fierce war that saw the death of nearly one percent of its population, Israel secured a grudging armistice with the Arab belligerents. The agreement brought an end to large-scale fighting, but failed to secure Arab recognition of Israeli independence, making further conflict inevitable.

In less than a decade, Israel once again found itself locked in a shooting war with its largest Arab neighbor. In response to Egyptian blockades of the Suez Canal and the Gulf of Aqaba, Israel launched an invasion of the Sinai Peninsula on October 29, 1956. The attack was coordinated with the British and the French, who dropped airborne forces near the Suez in the hopes of seizing the canal.

The affair ended in an embarrassing foreign-relations disaster for Great Britain and France as they were forced to accept a cease-fire due to pressure from the United States and the United Nations. Israeli forces had been stunningly successful during the ground campaign, seizing Sinai in short order. The IDF, though, had not been able to capture one of the most heavily defended of the Egyptian positions, the strategically vital high ground near the seemingly insignificant crossroads of Abu Agheila. The position was taken only after being abandoned by the Egyptians.

That brief war, though, was not without long-term ramifications. The fact that Britain and France had been forced to withdraw their troops due to political pressure only emboldened the Egyptians, and anti-Israeli rhetoric ramped up in the years that followed. As a result, the peacekeepers of the United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) were garrisoned in Sinai in order to keep the belligerents at arm’s length.

At the time, Egypt was experiencing a wave of nationalist fervor, largely due to the ascendance of Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser, one of the most charismatic leaders in the Middle East. Nasser had assumed the presidency of Egypt in 1954, just two years after he had helped orchestrate a successful coup. Nasser used powerful rhetoric that espoused greater unity for the Arab world, retribution for displaced Palestinians, and the reduction of the State of Israel.

Nasser’s magnetic charm also crossed national boundaries, and his promotion of pan-Arab unity found a wide audience across the region. By the mid-1960s, Nasser’s mounting influence in the Arab world was a source of grave alarm to Israel’s intelligence services. By 1964, IDF analysts predicted that a renewed war with an emboldened Egyptian army would likely occur as early as 1967.

Due to his previous professional contacts within the Egyptian Army, Nasser promoted a number of personal cronies to the highest ranks, chief among them Field Marshal Abdel Hakim Amer. Former vice president of Egypt and overall commander of Egyptian forces, Amer had seen extensive combat service. First commissioned in the Egyptian army in 1939, Amer had served against Israel in both 1948 and 1956 and had commanded Egyptian troops that intervened in the North Yemen Civil War.

Unfortunately, cronyism and statist paranoia gripped much of the Egyptian senior officer corps. Amer likewise appointed personal cronies or conferred promotion based on political considerations. A number of senior officers were known to possess a greater interest in Cairo nightlife than the military arts. Intelligence operatives spent much of their time monitoring suspect Egyptian officers rather than gathering intelligence on the Israelis. Ultimately, the misplaced focus on politics ensured that the Egyptian senior command bore a greater resemblance to an elite club of uniformed sycophants than a cadre of professional combat leaders.

Despite the shortcomings of the high brass, the Egyptian military possessed a vast arsenal of fearsome weaponry due to an alliance with the Soviet Union. Nasser’s increasingly hostile stance to the Western powers made him an attractive ally to the Soviets, who regarded him as a non-capitalist revolutionary democrat. Nasser and Amer were designated as Heroes of the Soviet Union in 1964 and awarded accompanying medals.

Such symbolic honorifics were accompanied with more concrete support in the form of modern weaponry. Since the close of the Sinai conflict, the Soviets had bestowed billions of dollars worth of military aid on the Arab states. The Arabs in the region fielded 1,700 tanks, 2,400 pieces of artillery, and 500 jet aircraft. Nearly half of the armaments went to Egypt, Israel’s most dangerous foe. Greater Arab unity likewise increased the threat to Israel. In October 1966, for example, Egypt and Syria secured a diplomatic rapprochement and signed a mutual defense pact.

The explosive combination of Arab military alliance and anti-Zionist rhetoric resulted in a dangerous powder keg for the greater Middle East. Misled by erroneous Syrian intelligence that pointed to an Israeli buildup on its northern border, Nasser and his generals grew increasingly jingoistic during the spring of 1967. On May 19, Nasser made the ominous move of requesting the removal of the 3,500 United Nations peacekeepers stationed in Sinai. With United Nation troops out of the way, Egypt began preparations for an inevitable war in Sinai.

The Middle East faced an irreversible crisis when Egypt ordered the closure of the Straits of Tiran—the strategic waterway that controlled the Gulf of Aqaba—on May 21, 1967. With Israeli access to the Gulf of Aqaba denied, Israel’s southern port of Eilat was entirely cut off from international waters. Widely regarded as an act of war, the closure of the Straits of Tiran was almost certain to result in conflict, and Nasser was unambiguous regarding the intention of his decision. “It will be total, and the objective will be Israel’s destruction,” he said, referring to a possible outbreak of war.

As diplomatic efforts (including proposed mediation) continued to fail, more Arab powers readied for war. In addition to Egypt and Syria, Jordan and Lebanon began mobilizing their armed forces. Even distant Muslim states including Iraq, Kuwait, Morocco, Libya, Saudi Arabia, and Tunisia either mobilized or contributed token forces to the fight against Israel. Ahmad ash-Shuqayri, chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization, gave voice to the mounting desire for war with an ominous public statement. “We shall destroy Israel and its inhabitants,” he said. “As for the survivors, if there are any, the boats are ready to deport them.”

Despite the overall lax condition of the Egyptian Army, the Israeli high command harbored a deep respect for the fighting mettle of the average Egyptian soldier. Largely due to Israel’s experience in failing to crack the defenses of Abu Agheila in 1956, the Egyptians were particularly feared for their willingness to fight tenaciously from fortified positions. Russian military engineers helped the Egyptians construct imposing fieldworks at key strategic positions across the vast expanse of Sinai.

A virtual panic gripped the highest echelon’s of Israel’s government as the nation braced itself for what could become a struggle for survival. Because any conflict would inevitably result in the IDF waging a war on multiple fronts, Israeli military doctrine stressed initiative and aggressive tactics as a part of an overall strategy of destroying numerically superior Arab armies before they had a chance to respond. In many respects, Israeli tactics ironically copied the blitzkrieg of Nazi Germany in World War II.

In the years leading up to the Sinai Campaign in the Six Day War, the IDF was transformed into a more mobile force that gravitated toward an armor-dominated army, as opposed to an army made up of predominantly infantry. Brigadier General Israel Tal, commander of the Israeli Armored Corps, was a key developer of his nation’s armored doctrine. In large part due to Israel’s small population, Tal favored heavy tanks and firepower at the expense of lighter and faster tanks. Such an approach offered Israeli tank crews better protection, as well as the upper hand during long-range armored duels.

Due to friendly relations and consequent arms contracts with the Western powers, tanks such as the American Patton and the British Centurion fit the bill. Israeli tankers received rigorous training in maneuver and gunnery. “After the air force, armor is the factor that decides the fate of battles on land,” said Tal. “The task of armor is to carry the battle into the enemy’s territory and thus obtain a quick decision.”

In any pending conflict, though, the vaunted Egyptian fieldworks in the vicinity of Abu Agheila could not simply be bypassed. With the assistance of Soviet advisors, Egyptian engineers had constructed a substantial barrier that would stall any potential Israeli advance with a robust defense in depth.

In front of the forward base at Umm Katif, Egyptian infantry manned two mutually supporting lines of trenches. The trenches were further bolstered by artillery positions, mortar pits, dug-in tanks, and bunkers. To the north, immense sand dunes, which were deemed impassable to armor, were considered effective flank protection. The eastern approaches to the position, the most likely avenue of an Israeli attack, were protected by wide belts of mine fields and barbed wire. Abu Agheila, which commanded the central route across Sinai, was likewise the most heavily fortified position on the peninsula.

Actually, the formidable task of cracking the defenses at Abu Agheila had commanded the attention of the Israeli high command since 1956. The Israeli Command and Staff College staged exercises each year against mock Abu Agheila fortifications, and the exercises were updated each year based on fresh intelligence of the ever-evolving Egyptian defenses. Most Israeli field commanders and staff officers were consequently familiar with the Abu Agheila defense complex. In keeping with Israeli doctrine, which promoted aggressive initiative from junior officers, participants in the program were encouraged to develop their own tactics in launching assaults.

Such intensive preparation for war, paired with reckless saber-rattling across the border, resulted in a fateful decision by the Israeli cabinet. In a series of tense meetings in a Tel Aviv bunker on June 4, Israeli military officers were nearly unanimous on the need to launch a preemptive attack on Egypt, which was continuing the Sinai buildup in preparation for launching its own attack. Quite understandably, the politicians demurred.

In the corner of the conference room, Brig. Gen. Ariel Sharon brooded. Sharon, who commanded one of the Israeli divisions mustered on the Sinai Front, was worried by the political indecision that left front-line troops in the lurch. Combat units were “moving here and there, crossing each other’s paths and taking up positions, only to move back from them a day later and take up different ones,” recalled Sharon. “The army did not look as if it knew what it was doing.”

Sharon took a grimmer view of the closure of the Straits of Tiran, and regarded it as a provocation that demanded an inevitable military response. “We have the power to destroy the Egyptian Army, but if we give in on the free-passage issue, we have opened the door to Israel’s destruction,” he said. “We will have to pay a far higher price in the future for something that we in any case had to do now.”

For the frontline commanders, continued diplomatic dawdling only invited a tougher fight. Every day that passed allowed the Egyptians more time to dig in and prepare. For his part, Sharon was exasperated by the waiting game. “The Army is ready as never before,” he said. “All this fawning to the powers, begging for help, undermines our case. If we want to survive here, we have to stand up for our rights.”

By the evening of June 4, such reasoning had swayed the government’s cabinet ministers, who, at last, opted for war. “The government has determined that the armies of Egypt, Syria, and Jordan are deployed for a multi-front attack that threatens Israel’s existence,” stated the official orders. “It is therefore decided to launch a military strike aimed at liberating Israel from encirclement.”

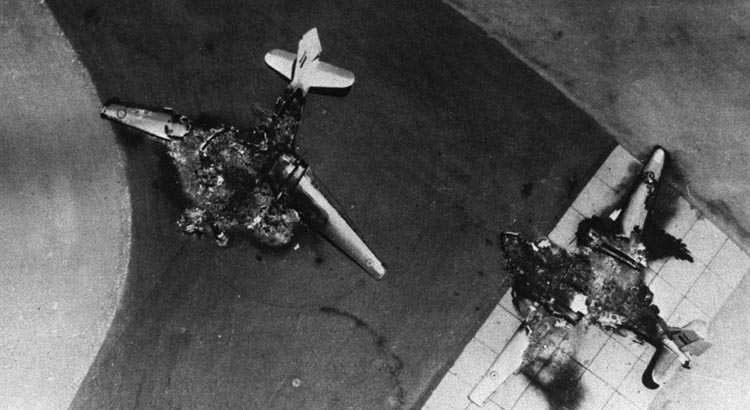

Those orders unfolded with startling force early on the morning of June 5, 1967. In a desperate attempt to neutralize Egypt’s formidable air power, the Israeli Air Force launched a stunning series of preemptive attacks on enemy airfields throughout Egypt. Known as Operation Moked, the attack caught the Egyptians entirely by surprise. In a matter of hours, approximately 200 Israeli aircraft conducted multiple attacks that eventually destroyed 338 Egyptian aircraft, most of which were never able to get off the ground. Subsequent attacks destroyed all 29 aircraft of the Jordanian Air Force, as well as 61 Syrian planes.

With the Arab air fleets out of commission, the Israelis were free to push their ground forces into Sinai free from the threat of aerial attack. Overall command of the Sinai Front was assigned to Brig. Gen. Yeshayahu Gavish. Gavish had three ugdah (divisions) at his immediate disposal. The Israeli right flank along the Mediterranean coast was commanded by Brig. Gen. Israel Tal, who led a division that was to sweep along the primary coastal route across Sinai. In the center, Brig. Gen Avraham Yoffe, a tough veteran who had seen extensive combat since he was 16 years old, led two armored brigades. On the left, Ariel Sharon commanded an imposing ugdah, the 38th Armored Division, which was a mixed outfit of four brigades that included armor, infantry, airborne, and artillery units.

A career army man, Sharon was a barrel-chested bull of a warrior to whom fighting had become a way of life. A native Israeli who had been born in British Palestine in 1928, Sharon was just 14 when he joined the Haganah militia. During the Israeli War of Independence, he served as a junior officer. Prone to lead by example, he was badly wounded in action with Jordanian troops.

Sharon was given command of a special forces outfit, Unit 101, in 1953. His tenure at the head of the commandos, though, would leave an indelible stain on his career as an officer. In October 1953, Sharon led an operation into the Jordanian West Bank that targeted Palestinian terrorists. During the fighting, more than 60 civilians were reportedly killed.

During the 1956 Sinai Campaign, Sharon commanded an elite unit of paratroopers that seized vital ground at the Mitla Pass. As a professional soldier, Sharon was regarded as a keen student and meticulous planner. On the battlefield, he earned the reputation as a hard-driving combat leader who was willing to personally lead his men into tough fighting.

Sharon’s objective was the imposing complex of Egyptian defenses around Abu Agheila, which commanded the central route across Sinai. The Egyptians were convinced that the main Israeli attack would be farther south, leading them to leave their forces spread woefully thin at Abu Agheila and the forward position of Umm Katif. Against the 8,000 Egyptians of the 2nd Infantry Division, Sharon had concentrated 14,000 Israeli troops.

Sharon also possessed a keen advantage in armor: 150 tanks consisting of a mix of Centurions, Super Shermans, and the lighter French AMX-13s. By comparison, the Egyptians could muster just 66 T-34’s. The Egyptians did possess an advantage in artillery, fielding a fearsome array of Soviet 122mm cannons and 152mm howitzers which easily outclassed the Israeli artillery.

Sharon had developed a meticulous and audacious plan for the reduction of the impressive Egyptian defenses. A keen student of military tactics, he not surprisingly opted for a massive flanking movement against the Egyptian stronghold. Following an airborne assault aimed at silencing the enemy artillery, Israeli artillery would unleash a punishing barrage on Egyptian positions. Armored columns would harass the enemy’s flanks while the main thrust, largely consisting of infantry, would strike the Egyptians from the north. The main attack would use the cover of sand dunes which the Egyptians considered impassable.

Clearly aware that Israeli troops had been stalled by the Abu Agheila defenses in 1956, Sharon had formulated an extremely complex plan in the hopes of completely overwhelming the Egyptian defenders. The success of the entire plan, though, would depend on near-perfect timing, the coordination of various columns, and a dose of good luck.

Sharon would have more than his share of good fortune in the unfolding battle. His main force crossed the border on June 5 and made for Abu Agheila. South of Umm Katif, Sharon launched a diversionary attack toward Egyptian positions at Qusaymah. Although he attacked Qusaymah with just two reserve battalions and a handful of tanks, the Egyptians became increasingly convinced that any direct attack on Abu Agheila was unlikely, and focused their attention on points south.

Taking advantage of the Egyptian confusion, Sharon put his complex plan in motion. On the right, Colonel Natke Nir’s task force struck off on one of the most crucial and dangerous parts of Sharon’s grand plan. Nir commanded an independent armored battalion, which was to swing to the north of the Umm Katif positions along an insignificant desert trail known as the Batur Track. His objectives were to reduce an Egyptian outpost at Point 181, then fall on the rear of Abu Agheila, seizing Ruafa Dam, cutting off the route of retreat and blocking the roads to any Egyptian reinforcements.

Nir commanded an assortment of heavily armed troops, which included mechanized infantry, mortar, and rocket teams, as well as reconnaissance and engineering units. The hard-hitting core of his unit consisted of 45 Centurion Mark V tanks, whose wide tracks made them well suited for the dangerous flank attack along the sandy wastes of the Batur Track. More important, the Centurions, armed with 105mm main guns, packed the necessary punch for a shooting match with Soviet-made armor.

Due to scant intelligence, Nir was unsure what resistance would be encountered at Point 181, but as his tanks approached the high ground, they received a warm reception and were driven back after fierce fighting. After calling in air support from the IAF, Nir struck again. While his infantry fixed the Egyptians from the front, Nir sent his armor on wide flanking attacks against the Egyptians.

In the face of the multi-pronged attack, Egyptian defenses at Point 181 collapsed, once again opening the Batur Track to Nir’s armor. The brutal fight for the position had cost Nir several of his subordinate officers and eight tanks.

The operation to seize Abu Agheila continued at sundown, when a daring helicopter-borne infantry attack was launched from Israeli positions. Sharon had planned for three waves of six helicopters to land 200 paratroopers in the enemy’s rear. The craft were carrying elements of the 80th Paratroop Brigade under the command of Colonel Matt. Matt’s elite paratroopers were tasked with the vital operation of silencing enemy artillery, consisting of deadly Soviet-made 130mm cannons, before the Egyptian guns could decimate Sharon’s advancing armor and infantry.

Sharon shared a special bond with his paratroopers. A former paratrooper himself, the general continued to don the red beret of the Israeli airborne. War correspondent Yael Dayan was present when Sharon conferred with Matt just prior to the attack. Sharon’s voice “changed some when he talked to the parachutists’ commander,” said Dayan. “He knew them all by first name, and they were his men, and somehow he gave me the feeling he was talking to a brother in whose hands he entrusted a hard job.”

Despite Sharon’s confidence in his paratroopers, the operation was indeed a hard job from the outset. During the flight to the landing zone, nearly half of the helicopter pilots lost their bearings in the darkness, veered far off course, and never succeeded in landing their loads of paratroopers at the designated target. After a harrowing flight over the desert, the rest of the helicopters touched down about two miles northwest of the Egyptian artillery park in terrain considered impassable to the Egyptians. Matt’s paratroopers, each of whom was laden with a heavy load of weaponry and equipment, began the arduous trek toward their target.

Although the paratroopers were highly conditioned warriors, they struggled under heavy loads as they trudged through the sand dunes. Urged on by their officers, the men pressed forward. With no warning, Egyptian artillery and mortar fire began landing on the planned route of attack, sending up great plumes of sand and dust. Matt kept his head despite the tremendous crash of artillery. “I guessed from the location of falling bombs that the enemy was firing blind, not having actually seen us, only hearing the unfamiliar noise of the helicopters in their rear area,” said Matt.

Despite the occasional burst of Egyptian illumination rounds, the paratroopers struggled to find their way in the dark; but as Matt pressed forward, the enemy position was clearly located by the telltale muzzle flashes of Egyptian artillery. Matt and his men reached the perimeter of the Egyptian artillery park at 12:00 AM. They then formed up for the planned assault.

As the Israelis rushed forward, they could not believe their luck. The artillery position they were about to assault, which had no protective minefields or barbed wire, was wide open to attack. Matt had given orders to individually assault each enemy gun, and as the paratroopers entered the position, they split up to target their objectives. The Egyptian gun crews had been taken entirely by surprise and panicked in the confusion. The Israelis likewise targeted enemy ammunition bunkers, which were soon engulfed in flames. In minutes, the Egyptian gun crews had scattered in confusion, and much of the artillery was destroyed or disabled.

A convoy of Egyptian supply trucks, illuminated by their own headlights, arrived unexpectedly at the artillery park just as the Israelis had overrun the position. The disoriented Egyptian drivers had no warning and drove into the mouth of a deadly ambush. Riddled with Israeli small arms fire, trucks careened out of control or burst into flames.

While Matt was shocked by the carnage his men had inflicted, the operation to silence the Egyptian guns had been a remarkable success. For his part, Matt had regarded his assignment as sure to result in a tough fight, and he was elated with his success. As his men mopped up and gathered their dead and wounded, Matt received a radio communication from Sharon, who ordered the paratroopers evacuated. The main attack could proceed unfettered by the threat of an impenetrable Egyptian artillery screen.

Israeli columns would make the most of the advantage. Sharon gave orders for his artillery to open fire on the Egyptians at 10:00 PM. His arsenal of firepower consisted of 105mm and 155mm howitzers, 120mm and 160mm mortars, and British 25-pounders. As he glanced across the desert, he issued legendary orders for his gunners. “Let everything tremble,” he said.

A sheet of flame lit up the desert floor as the guns opened up, raining down an unrelenting storm of fire on the Egyptian defenses. For nearly half an hour, the Israelis unleashed the most intense artillery bombardment in the history of the IDF. Even Sharon, a career soldier, was amazed by the tremendous show of firepower. “I have never seen such a fire in all my life,” he said.

In the hope that the fierce shelling had softened up the Egyptian defenses, Sharon unleashed the troops of his main assault. Thundering toward the Egyptian lines were the tanks of Lt. Col. Mordecai Zippori’s 14th Armored Brigade, containing two battalions of Super Sherman tanks mounting 105mm guns. Zippori’s task was to seize forward Egyptian observations posts and then use his armor as fire support for the infantry attack on the main Egyptian trenches. Zippori’s tankers had faced determined opposition at the forward Egyptian post at Tarat Umm Basis, which was occupied by the elite members of Egypt’s 2nd Reconnaissance Battalion. The Egyptians broke after two hours of fierce fighting, and Zippori’s brigade continued to steamroll startled enemy outposts as it drove forward.

Israeli momentum, though, soon ground to a halt. Although the IAF began launching sorties against the enemy defensive complex centered on Abu Agheila, Egyptian artillery was able to maintain a heavy and accurate fire against the advancing Israeli armor. To avoid sending his tanks into a killing zone, Zippori ordered his tank crews to stop the advance.

Earlier that afternoon, Sharon ordered his infantry, the Kuti Brigade commanded by Colonel Yekutiel Adam, to cross the frontier and move toward Umm Katif. Adam’s three battalions, one of which was a part-time reserve outfit, had ridden to the front in a curious parade of civilian vehicles. After reaching Tarat Um Basis, the foot soldiers dismounted and trudged a dozen miles through sand dunes to the north of the enemy.

Adam’s brigade, which was tasked with assaulting the lines at Umm Katif, had taken up its assault positions on the Egyptian left by 10:00 PM. Adam opted to throw his two regular battalions into the initial assault and hold back his part-time reservists as a general reserve in case of emergency. Once again, the Egyptians would be confounded by the direction of the attack, which came from sand dunes that were considered impassable. To the north of the Umm Katif position, the Egyptians had planted no mines.

Rushing in from the dunes in the black of night, Adam’s men slammed hard into the trenches, quickly folding the Egyptian left. The Egyptians, though, quickly regrouped and put up a stiff fight; brutal hand-to-hand combat ensued in the trenches. The Egyptian colonel in command of the defenses, whose command bunker was located in the second line of trenches, frantically tried to order artillery strikes against the Israeli-occupied first trench. His position, though, was overrun by the advancing Israelis, who captured the command staff.

Despite the determined defense of much of the Egyptian infantry, the tactical surprise gained by the Israelis began to tell. Israeli infantry rapidly moved through the trenches. In the confusion of the night fighting, the foot soldiers averted friendly fire incidents by use of colored signaling flashlights. Each battalion had a specific color. One was red, another green, and yet another blue. By 1:00 AM on June 6, the Israelis sat astride the central route and began assaulting the southern half of the Umm Katif defenses. Clearly sensing that he was poised for victory, Adam ordered his reserve battalion into the fight.

The situation quickly degenerated for the Egyptians. Soon after Adam’s successful assault of the trenches, Israeli engineers succeeded in opening a hole in the minefields and barbed wire to the east of Umm Katif so that Israeli armor could advance. The operation would be a difficult one, though. As a lead platoon of tanks inched its way through the gap, one of the tanks struck a mine and was disabled, blocking the path. The engineers frantically worked to widen the breach for the remainder of the tanks. Only the mounting confusion in Egyptian ranks saved the stalled tanks from annihilation. Three hours later, Israeli tanks were pouring through the gap and widening the Israeli breach of the Umm Katif position.

After a harrowing nightlong journey through the sand dunes north of Abu Agheila, Natke Nir finally succeeded in getting his Centurion tanks in position for an assault on Egyptian troops stationed at Ruafa Dam. His attack, which rolled in from the west, came as a complete shock to the startled Egyptian defenders, whose attention had been focused on the main attack coming from the east. In short order, the Egyptian position collapsed, and Nir struck east in order to link up with the Israeli main body.

At that point, the Egyptian defenses began to hopelessly unravel. For two hours, Egyptian tankers waged a determined but uncoordinated fight with the closing vise of advancing Israeli armor. By the early morning hours, only isolated detachments of Egyptians continued to fight, but they were quickly overwhelmed. The Egyptian defensive works of the Abu Agheila complex, once considered one of the strongest defensive positions in the world, had fallen in a single night of fierce fighting.

The loss of Abu Agheila, paired with startling Israeli victories farther north, brought about the entire collapse of the Egyptian defense of the Sinai Peninsula. In Cairo, a demoralized Field Marshall Amer panicked and ordered his entire army to give up the fight, make for the Suez Canal, and regroup on the west bank. By the early afternoon, Egyptian forces were in full flight to the west, with hard-driving Israeli armored columns hot on their heels.

Far from letting the Egyptians escape, the Israelis sent smaller armored forces in a mad dash for the few strategic passes through the mountains of western Sinai. Once again, decisive action enabled the Israelis to gain control of the only Egyptian escape routes. Although a good number of Egyptians escaped, the outcome of the fighting in Sinai had proved nothing short of catastrophic. The Egyptian Army had lost 80 percent of its tanks, artillery, and trucks. The Egyptians also suffered 11,000 men killed, wounded, or captured. In the Abu Agheila sector alone, the Egyptians lost 2,000 men and 60 tanks. In contrast, the Israelis lost 40 men and 19 tanks in that sector.

The remarkable victory in Sinai had outpaced the most optimistic of Israeli timetables and exceeded even the wildest dreams of Sharon. The 38th Armored Division’s remarkable success at Abu Agheila not only secured Ariel Sharon’s reputation as a cunning strategist, but also was a key factor in the crushing Israeli victory during the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, which lasted less than a week. During the conflict, later styled the Six Day War, the IDF stormed to stunning wins on every front.

In addition to occupying the Sinai Peninsula and the Gaza Strip, the Israelis crushed Syrian columns in the northeast, securing possession of the strategic Golan Heights. Israeli possession of the Golan ensured that Jewish farmers, who had faced perennial shelling from Syrian artillery on the heights, would enjoy a level of security heretofore unknown.

Similarly, the Israelis delivered crippling blows to enemy troops in the West Bank. Despite stubborn Jordanian fighting, the IDF badly wrecked Jordanian columns. The fighting left Israel in control of all territory west of the Jordan River, which included the holy city of Jerusalem, the most treasured prize in the Middle East.