By William E. Welsh

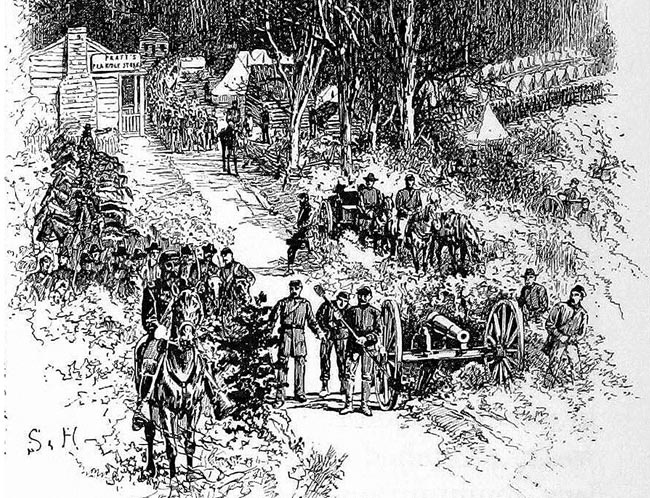

Union artillery shells burst in the trees at the north end of Cross Timber Hollow as Confederates in gray and butternut-colored uniforms creeped through the tangled underbrush on both sides of Telegraph Road. Shell and case shot from the Union guns ripped through the leafless trees, showering the Rebels with heavy branches and razor-sharp splinters. The Iowan gunners maintained a brisk rate of fire from a section of 6-pounders that Colonel Eugene A. Carr had placed near the southern exit of the hollow to sweep the road.

The well-served Union guns forced Maj. Gen. Sterling “Old Pap” Price’s infantrymen to scuffle along the steep sides of the gorge, where they slipped on loose rock and patches of snow and ice. The isolated fight near Elkhorn Tavern on the east side of Pea Ridge in northeastern Arkansas was well underway by late morning on March 7, 1862.

Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn, who commanded the Trans-Mississippi District, had rallied the Rebels who had withdrawn from Missouri into northeastern Arkansas in winter 1861-1862, owing to a lack of popular support in the state. Arriving in Little Rock, Arkansas, in late January to take his new command, Van Dorn combined Brig. Gen. Ben McCulloch’s division of Deep South soldiers and Price’s Missouri troops to form the Army of the West, numbering 16,000 men.

Van Dorn led the Army of the West north from the Boston Mountains on a grueling, 55-mile forced march conducted in a late winter snowstorm. He planned to whip Brig. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis’s Army of the Southwest and retake Missouri. The Rebels, who consumed the last of their rations on the march, hoped to soon be dining on captured Union provisions.

Having been forewarned that the Confederates were headed his way in force, Curtis entrenched his 10,500 men on the bluffs on the north bank of Little Sugar Creek to await the Rebel onslaught. To their rear was Pea Ridge, a two-mile-long elevation with granite outcroppings. Situated perpendicular to the ridge on its east side was Cross Timber Hollow. Telegraph Road traversed the heavily wooded hollow. The southern terminus of the telegraph wire was a two-story inn known as Elkhorn Tavern, which was situated about two miles north of Little Sugar Creek.

Van Dorn correctly reasoned that Curtis had a long and vulnerable supply line, and he intended to conduct an elaborate envelopment of the Union army by a wide flanking march to the west. Leaving their camp fires burning on the night of March 6 in an attempt to deceive the Yankees, the Confederates tramped north through the dark night.

Price’s division led the way on the Old Bentonville Road, and McCulloch’s division followed close behind. McCulloch, who had the shorter route, would turn off first, heading southeast to gain the Union right rear on the west side of Pea Ridge. As for Price, he would continue around Pea Ridge to the north and then make a sharp turn south into Cross Timber Hollow in order to strike the Union left rear. Van Dorn accompanied Price’s Missourians to ensure that they stayed on schedule.

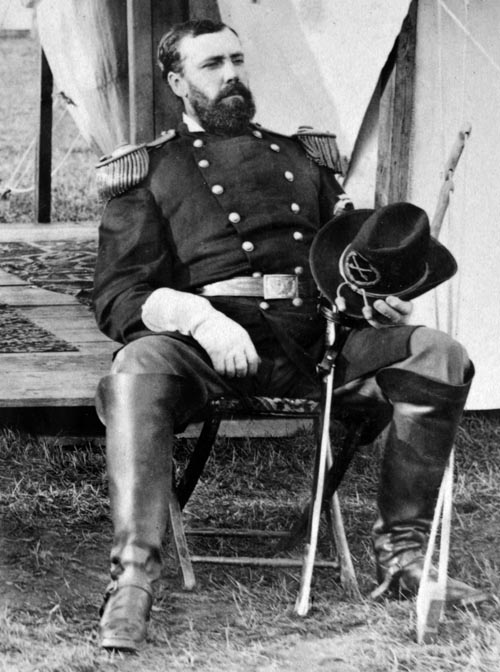

New York-native Eugene M. Carr graduated in West Point’s Class of 1850. He had extensive experience in the pre-war U.S. Cavalry fighting Indians. His commanding officers on the frontier had found him to be an ill-tempered and quarrelsome subordinate. Yet they respected the leadership and courage he demonstrated in battle. His dark facial hair and intense expression while in the saddle prompted his fellow officers to nickname him the “Black-Bearded Cossack.”

On the eve of the Battle of Pea Ridge, Carr commanded the 4th Division in the Army of the Southwest. Carr’s division comprised Colonel Grenville Dodge’s First Brigade and Colonel William Vandever’s Second Brigade. Each brigade had an artillery battery. Captain Junius Jones, 1st Iowa Light Artillery, supported Dodge’s infantry, while Captain Mortimer Hayden’s 3rd Iowa Light Artillery was assigned to Vandever’s brigade.

The 1st Iowa Light Artillery, which would play a crucial role in the unfolding clash near Elkhorn Tavern, had been mustered in Burlington, Iowa. It transferred to St Louis in December 1861, where it received its four 6-pounders and two 12-pounder howitzers. The artillery unit joined Curtis’ army in the field the following month. The artillerymen received their baptism of fire that day.

Carr’s mounted scouts informed him at 10:30 a.m. that a Confederate force of unknown size was entering Cross Timber Hollow. Curtis assumed that the threat from the north was a diversionary attack. The Union army commander would not know for sure, though, until he dispatched a reliable subordinate to assess the situation. He rode to Carr and informed him that he should march his troops north to contain the Confederate attack on the Union rear. “[You will] clean out that hollow in a very short time,” Curtis said optimistically.

On the assumption it was a small Confederate force, Curtis initially held back Vandever’s brigade. This left Carr with just Dodge’s 950 infantrymen and 310 cavalrymen to fight Price’s division. Dodge’s brigade consisted of the 4th Iowa, 35th Illinois, 24th Missouri Cavalry, and 1st Iowa Light Artillery.

Upon arriving at the south end of the hollow, Carr dispatched Dodge with the two infantry regiments to deploy along Huntsville Road, which ran east from Telegraph Road at the south side of the hollow. Carr placed the 24th Missouri cavalry and one company of infantry from the 35th Illinois on the west side of Telegraph Road to cover another north-south defile known as Tanyard Ravine. As for Jones’ battery, he divided it into three sections. He sent a pair of 6-pounders with Dodge to buttress his right wing, he retained two 6-pounders at the point where Telegraph Road exited the hollow, and he sent a pair of 12-pounder howitzers to Elkhorn Tavern to hold in reserve.

Price’s troops had straggled badly on their various marches. By the time he began deploying for battle on March 7, he had 5,000 men on hand. These were still heavy odds, as Carr would soon discover.

Price soon had his troops in a long battle line. Colonel Henry Little’s 1st Missouri and Colonel William Slack’s 2nd Missouri brigades both arrayed their troops into battle lines.

Colonel William Slack’s 2nd Missouri brigade advanced south into Tanyard Ravine west of Telegraph Road, while Colonel Henry Little’s 1st Missouri Brigade began moving south astride Telegraph Road. Further east, the Missouri Guard units formed up to assail Dodge’s two infantry regiments. The roar of battle increased substantially at 11:30 a.m. as the Confederate infantry made initial contact.

Carr initially intended to fight a defensive action, but he soon realized that he was heavily outnumbered. He sent a courier to Curtis requesting Vandever’s brigade immediately because he was hard pressed. Curtis agreed. Carr reasoned that it would be an hour or more before Vandever’s infantry arrived.

Carr decided on a bold tactic. He would accompany Jones with the two 6-pounders in the center of his line into the hollow to thwart the Confederate advance as long as possible. The two limbered guns rolled 300 yards downhill into the hollow. Carr ordered Jones to unlimber on the right side of Telegraph Road in such a way that the guns could sweep the road. The guns were squarely pointed at Little’s 1st Missouri.

When the Iowans opened fire with their two 6-pounders, some of the Confederate regimental commanders ordered their men to lie prone. The Union artillery fire prompted Van Dorn to rush forward the Confederate batteries at the back of the column. This took time. The first to go into action was Captain Henry Guibor’s Battery, composed of two 6-pounders and two 12-pounder howitzers. The Confederate counter-battery fire grew in intensity as more batteries went into action on a shelf at the north end of the hollow.

Jones’ artillery crews had a hard time firing downhill. Even though most of their shot did not land amidst the infantry and the Confederate casualties were light, the Confederates chose not to advance directly down the road. Instead, the foot soldiers moved slowly along the slopes on each side of hollow; however the half- frozen landscape with its slick slopes bedeviled the Rebels.

Confederate shells inflicted horrific wounds on some of the Iowan artillerists. A dozen of Jones’ artillerymen received severe wounds. One had his left leg sheared off, another was struck by a ball in the groin, and yet another was struck in the mouth by shrapnel. A spent shot struck Jones in the leg, compelling him to hand over command to Lieutenant Virgil David. “We stood in the tempest of death,” wrote Union artillerist Sam Black. “I believe every man at the guns had made up his mind to die there, for it did not seem possible that any of us could get out alive.”

Despite the carnage, the intrepid Iowans maintained a brisk fire as Carr watched from a position nearby. Carr had called for the two 12-pounder howitzers held in reserve to be brought forward to help offset the steep odds he faced as Price’s troops brought more batteries forward. Although Carr’s place should have been behind the infantry, he was determined at all costs to retard the Confederate advance until such time as Vandever’s blue-coated infantry arrived.

The Confederates eventually had 21 guns in action against Jones’ four artillery pieces. The Confederates scored direct hits on two caissons, which produced enormous explosions. The horses on another caisson raced away, tipping over a third caisson. Carr was wounded three times while supervising the forward artillery position in the hollow. Although not life-threatening, the three wounds were exceedingly painful. He was struck in the wrist, neck, and ankle.

Carr summoned Colonel Gustavus Smith to bring forward a portion of his 35th Illinois to furnish support for the beleaguered artillerymen. On the right of Carr’s line, the Missouri Guard struck Lt. Col. John Galligan’s 4th Iowa. Fortunately, Galligan’s foot soldiers stood their ground and repulsed two determined attempts to turn their flank in the early afternoon. It soon became imperative for Carr to make adjustments so that Dodge’s troops would not be cut off from the rest of the army.

By 12:30 p.m., the Rebel gunners had silenced three of the four Iowa guns contesting the passage of Rebel infantry along Telegraph Road. When Vandever’s brigade arrived to reinforce his position, Carr ordered the shattered 1st Iowa Light Artillery to withdraw to Elkhorn Tavern. Orders were issued for the Union gunners to detonate the overturned artillery chest before withdrawing. Meanwhile, Vandever sent his lead elements into action on the Union left to check the advance of Slack’s 2nd Missouri troops, who were making good progress through Tanyard Ravine. The 3rd Iowa Light Artillery unlimbered its guns to cover the withdrawal of its fellow artillerymen. At that point, Carr moved to establish a division command near Elkhorn Tavern. Not long afterwards, Price’s troops switched to the defensive, for Old Pap was convinced he could not displace Carr’s division.

Carr was promoted to brigadier effective the date of the Battle of Pea Ridge, in which he performed so heroically. He went on to command the Fourteenth Division of the XIII Corps at Vicksburg in 1863. In the final stages of the war, he commanded Union troops in Arkansas. After the war, he returned to Indian fighting on the western frontier. He retired from the regular army with the rank of brigadier general in 1893.

The following year, Congress decided to award him the Congressional Medal of Honor for his outstanding performance at Pea Ridge. Carr “directed the deployment of his command and held his ground, under a brisk fire of shot and shell in which he was several times wounded,” stated the citation. It was a most deserved and fitting tribute to one of the Union army’s best generals during the War Between the States. Carr was 80 years old when he passed away in 1910 in Washington, D.C. He was buried with honors in West Point Cemetery.