By Bob Gordon

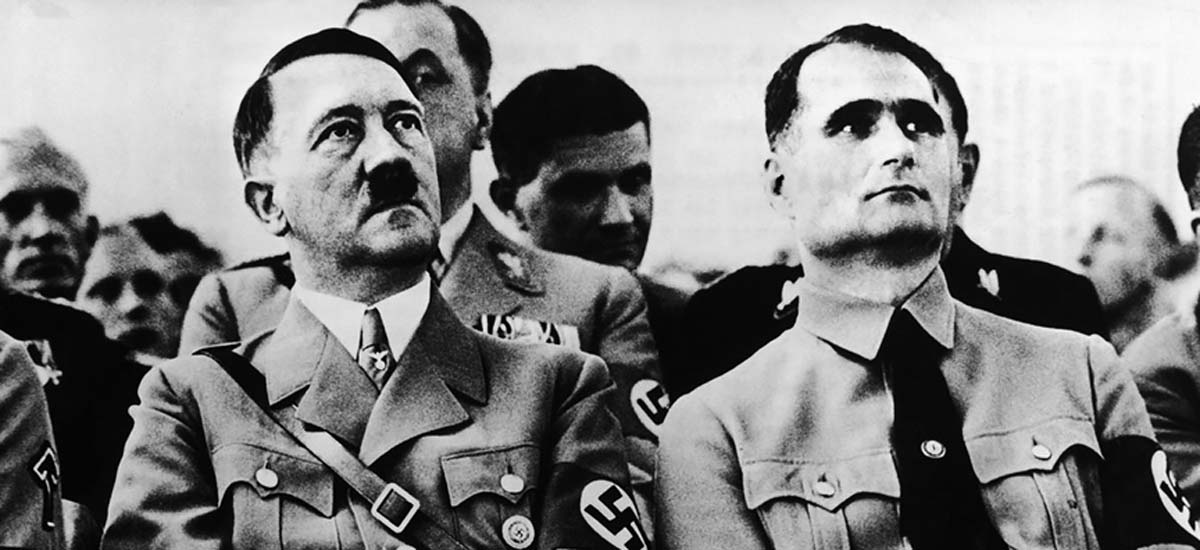

In October 1939, British Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill famously described Russia as “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.” The same could be said of Rudolf Hess, the Nazi leader and Nuremberg war criminal who spent the last four decades of his life in Spandau Prison in Berlin. In the 15 years following World War I, he rose from being a shy and introverted but brilliant university student to the height of power in Nazi Germany as deputy Führer, second only to Adolf Hitler himself. He ended his life at age 93, a feeble, captive, old codger.

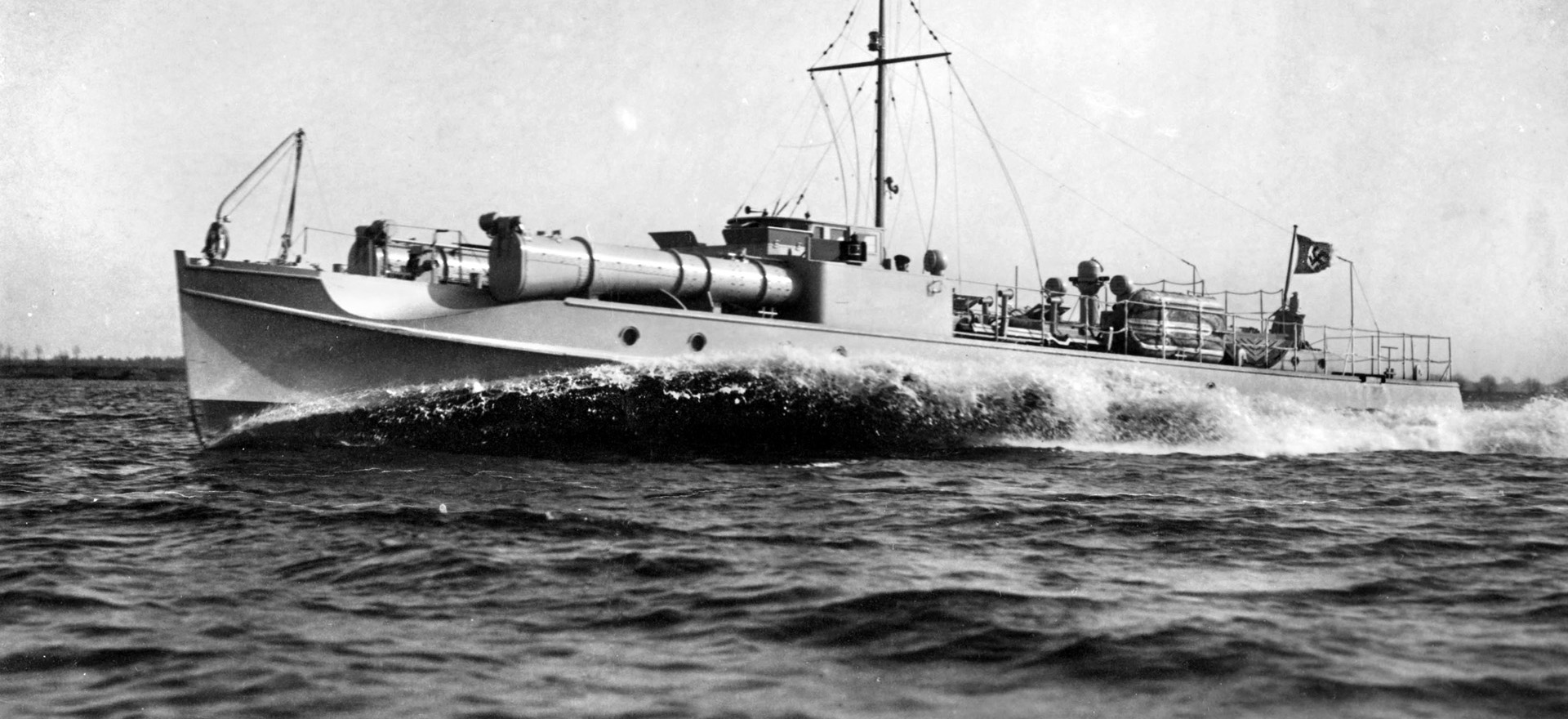

On May 10, 1941, only weeks before Operation Barbarossa, the planned German invasion of the Soviet Union, he flew from Augsburg to Scotland, apparently on a freelance diplomatic mission. He planned to make peace with Great Britain and avert the age-old German specter of a two-front war. Needless to say, he was singularly unsuccessful and imprisoned until transferred to Nuremberg for the war crimes trials held after the war. Since that fateful Saturday, the first anniversary of the German invasion of France, myths and misinformation have shrouded this undeniably eccentric Nazi.

Hess’s Obsession with Astrology, Ghosts, Telepathy, and Mesmerism

His curious diplomatic mission is only the tip of the inexplicable iceberg that is Hess. Prior to his flight, his companions regarded him as extremely odd, even mentally unbalanced. Herman Göring described him as “mad,” and Hitler often mocked his reliance on astrology, ghosts, telepathy, and mesmerism. Ernst “Putzi” Hanfstaengl, a German-American businessman close to Hitler, recalled that Hess “would not go to bed without testing with a divining rod whether there were any subterranean water-courses which conflicted with the direction of his couch.” Others remembered watching him hang magnets over his bed. Even in the Führer’s circle of “bohemians and condottieri,” to use Hitler biographer Ian Kershaw’s colorful turn of phrase, Hess stood out for his peculiarities.

Dr. Kelley S. Douglas, the official U.S. government psychiatrist who examined Hess during the war crimes trials, concluded pithily, “Diagrammatically, if one considers the street as sanity and the sidewalk as insanity, then Hess spent the greater part of his time on the curb.” In all seriousness, Hess asserted to Lt. Col. Eugene K. Bird, U.S. commandant of the Spandau Allied Prison from 1964 to 1972, that if his mission had succeeded, he would have received the Nobel Peace Prize! In this century, psychiatrist Dr. Joel E. Dimsdale reassessed the accused at Nuremberg, concluding Hess exhibited “consistently abnormal behavior, which extended over years, spanning events before, during, and even after the trial.”

Questions arise, thus, such as who was Rudolf Hess? What were his beliefs and intentions? What were the forces that animated his psyche? His personality? These questions must also be considered in an existential sense, because it has been posited that the prisoner in Spandau was not the man born Rudolf Walter Richard Hess in Alexandria, Egypt, on Thursday, April 26, 1894. Only recent research published earlier this year has resolved this fundamental issue.

Finally, and as is only fitting, there are significant questions surrounding his death on August 17, 1987, at the age of 93. It was ruled a suicide. However, as is always the case with Hess, questions remain. Many, including his late son Wolf Rutiger Hess, believed it was a politically motivated assassination. Even in death, Rudolf Hess remains a mystery.

Finding Relief in War in 1914

Hess was born in Egypt, his father operating an import/export business in Alexandria. He was raised in an affluent environment and educated at the Protestant School in Alexandria. At 14, he was sent to the Evangelical School in Bad Godesberg in northern Bavaria, close to the family’s summer home in Reicholdsgrün. His father insisted that he prepare to join the family business, Hess & Co. Against his will and the recommendation of his teachers, his father compelled him in 1911 to study at the École Supérieure de Commerce in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, and then apprentice himself at a trading company in Hamburg.

Forced into a career path he resented, driven by a distant and domineering father, Hess greeted the declaration of war in 1914 with relief. He immediately enlisted in the 7th Bavarian Field Artillery Regiment, and on November 9, 1914, transferred to the 1st Infantry Regiment. In January 1918, he transferred to the Deutsche Luftstreitkräfte (German Air Force) and completed training, earning promotion to Leutnant der Reserve, although the war ended before he flew any combat missions. He survived the war and was awarded the Iron Cross 2nd Class, having suffered multiple wounds. (Read more about the exploits of WWI—from both sides of the fighting—inside the pages of Military Heritage magazine.)

Most importantly, Hess felt crushed, shamed, and angered by Germany’s defeat in World War I and believed that his country had been humiliated by the Treaty of Versailles. According to his future wife, Ilse Pröhl, he “was a string taut to the point of snapping, on which the fateful song of Germany’s distress was unendingly played.” He joined the Aryan fantasists in the Thule Society, many of whom were future Nazis, and on May Day 1919, while fighting Spartakusbund (Communist) paramilitaries with Freikorps Epp in the streets of Munich, he was wounded again.

Slavish Submission to the Führer

His impotent rage became transformed when the young veteran, now a student of geopolitician Karl Haushofer at the University of Munich, heard his fellow veteran Adolf Hitler speak for the first time. He raved about the man to his fiancée. Contemporaries report that his entire demeanor changed. Unrelievedly somber, they noted that he smiled again and voiced optimism for Germany’s future. After a single dose of Hitler’s oratory, Hess was enthralled, so on June 30, 1920, he joined the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP). His membership number was 16, immediately preceding Julius Streicher, the infamous Nazi Jew baiter and publisher of the racist newspaper Der Stürmer.

In terms of submission to the Führer, Hess quickly emerged as number one, and the Führer reciprocated. In September 1920, Hess wrote ecstatically to his parents, “I spend nearly every day with Hitler.” The next spring, he told a cousin, “A splendid person!… He comes from a humble background, and has acquired a vast knowledge on his own, which I greatly admire.” Universally, his Nazi contemporaries commented on his slavish submission to the Führer.

German historian Volker Ullrich describes Hess as one of the first “Hitler disciples.” British historian Ian Kershaw asserts that Hess was “besotted” by Hitler. Still a student, he entered a University of Munich essay contest in the fall of 1922 in which he asked, “What qualities will the man have who leads Germany back to the top?” Hess’s answer to this question won by his descriptions of Hitler’s “deep knowledge in all areas of the life of the state and its history, the ability to learn lessons from them, belief in the purity of his own cause and in ultimate victory, and an untamable strength of will that give him the power of captivating oration that makes the masses celebrate him.”

Even during his imprisonment in Landsberg after the failed Munich Putsch in 1923, he maintained an almost religious belief in his Führer, writing to his wife, “Hitler is the man of the future in Germany, the dictator whose flag will fly sooner or later over public buildings in Berlin. He himself has faith enough to move mountains.” At Nuremberg a quarter century later, American psychologist Dr. G.M. Gilbert characterized his hyperbolic loyalty as “doglike devotion.”

For a future dictator already fully dedicated to his own personality cult and who valued loyalty and obedience above all else, Hess was the perfect acolyte. Winnifred Wagner, the granddaughter of composer Richard Wagner, wrote, “Wolf [Hitler’s nickname] is so attached to Hess—he’s constantly singing his praises.” Hitler would stand as best man at Hess’s wedding and become godfather to his son, Wolf. Significantly, he allowed Hess to address him with the intimate “du” rather than the more formal German form of address “Sie,” a familiarity Hitler extended to very few.

The 1923 Munich Putsch attempt and its aftermath illustrates their closeness. Hess played a leading role in the attempted coup. He was assigned to make the arrests in the Bürgerbräukeller, including Bavaria’s ruling triumvirate of State Commissioner Gustav Ritter von Kahr, Generalmajor Otto von Lossow, and Munich police chief Hans Ritter von Seisser. He held them hostage while the putsch collapsed, briefly hid out at Karl Haushofer’s apartment, and then fled to Austria. He only surrendered to German authorities after Hitler was sentenced to Landsberg Prison, where he happily joined him.

Despite the spurious but widely repeated myth, Hitler did not dictate Mein Kampf to Hess. This erroneous report by a guard is easily explained. Often on Saturday evenings, Hitler would read completed chapters to his fellow Nazi prisoners. He was not dictating to Hess. That said, Hess played an important role in the book’s genesis.

The concept of Lebensraum (living space) was a theme of Haushofer’s that Hess, his student and personal assistant, introduced to Hitler. Hitler may not have read Haushofer, but Hess would most certainly have shared Haushofer’s theories and concepts of geopolitics. In this view, vital space is essential, and dynamic nations expand into it, aiming at autarky—economic self-sufficiency. Conflict is inevitable, and victory is indicative of a healthy, dynamic nation. In the case of Germany, Haushofer concluded that this vital space was the Ukrainian breadbasket and the oil fields surrounding the Caspian Sea. The closeness of the Haushofers and Hess cannot be overstated and, consequently, neither can Karl Haushofer’s indirect influence on Hitler. His theories, delivered through Hess, gave Hitler’s thinking on Germany’s destiny to expand eastward an intellectual veneer.

Hess was Hitler’s amanuensis also. He wrote, “Hitler regularly reads to me from his book. Whenever a chapter is done, he takes it to me. He explains it to me, and we discuss the odd point.” Hess also assisted in other more mundane tasks. “My daily routine begins as follows: at 5 AM, I get up and make cups of tea for Hitler (who is writing his book) and myself.” Finally, he copyedited the final draft of the manuscript. Evidence of Hess’s obeisance to the Führer abounds within the devotional narrative of his imprisonment together with his beloved Hitler.

This close, symbiotic relationship persisted through the decade between the putsch and Hitler’s seizure of power in 1933. Hess identified a unique type of “German democracy” defined by “absolute authority directed downwards, and absolute duty directed upwards.” For Hess, this was more than a political theory: it was a deep-seated, psychological need and a sacred, personal commitment. Three months after assuming power in January 1933, Hitler rewarded him with the designation of deputy Führer. On the basis of this label, he was entitled to sit in on cabinet meetings, but he was given no official government role. His exclusive responsibility instead extended to Nazi Party matters.

Hess’s introversion, his idiosyncrasies, and his dedication to Hitler, rather than his own career, sentenced him to the periphery of power. He was bested in internecine quarrels by Luftwaffe chief Göring (who was also in charge of the Four-Year economic plans) and Himmler, who established his own military-economic fiefdom with the Schutzstaffel (SS). After the invasion of Poland, military matters increasingly took precedence over party matters, further pushing Hess to the periphery of power.

Supplanted by Martin Bormann

Compounding Hess’s difficulties, his assigned domain of authority, the Nazi Party, was an amorphous, diffuse entity not a disciplined, reliable power base as was the case with, for instance, Himmler’s SS. Orders issued by Hess from the center could easily be subverted by regional gauleiters, who could appeal directly to the Führer based on decades of personal camaraderie. According to Kershaw, “Hess’s ability to survive had less to do with his own battling nature than with the persistence and tactical cleverness of [his chief of staff] Martin Bormann.” Eventually, Bormann turned those skills on his boss in his successful drive to supplant him as an intimate of the Führer.

Albert Speer’s recollection of Hitler’s first words upon being informed of Hess’s flight says it all: “Bormann, immediately! Where is Bormann?” By the spring of 1941, the Führer was increasingly turning to Bormann when crises arose. Two days after Hess’s flight, the position of deputy Führer was abolished, and Bormann, already Hitler’s personal secretary, was appointed director of the newly established party chancellery.

It was this gradual marginalization from the inner circle that explains Hess’s quixotic flight to Scotland. It was a flight of fancy. He had persuaded himself that a personal intervention through the Duke of Hamilton would convince the British elite of Germany’s regard for the British Empire and its sincere desire for an alliance against the Soviet Union. Operation Barbarossa loomed, time was of the essence, and desperate measures were called for.

Most important to Hess was the promise of a diplomatic breakthrough bringing him back into the circle of the elect in the eyes of his Führer. He hoped that his intuitive understanding of the Führer’s goals, his commitment, and his daring would return him to the feet of the throne. Insightfully, Churchill later imagined Hess’s inner dialogue as he contemplated his mission: “I, Rudolf, by a deed of superb devotion, will surpass them all and bring to my Führer a greater treasure and easement than all of them put together.” As unlikely and even delusional as this belief was, it impelled him to act.

Remarkably, Hess had not kept his deliberations secret. His senior adjutant found out inadvertently, but kept silent. Hess had also discussed the issue with his mentor, Karl Haushofer, and Haushofer’s son Albrecht, who was a close friend. Replying to a memorandum Albrecht sent him regarding future Anglo-German relations, Hess asked who specifically in the upper echelons of the British elite could be approached about an Anglo-German rapprochement. Albrecht responded with a long list of politicians, nobility, and diplomats, concluding with the Duke of Hamilton, “the closest of my English friends.” Albrecht Haushofer and the duke had met at the 1936 Berlin Olympics. The duke was the co-author of Pilots Over Everest, which told the story of his flight above the world’s tallest peak. More specifically, he had presented a copy to the elder Haushofer, who had in turn loaned it to Hess. No mystery surrounds Hess’s choice of the Duke of Hamilton as an intermediary, although they had never been introduced. Unaware that the duke was on active service with the Royal Air Force, Hess chose Donvegal, Hamilton’s Scottish estate, as his destination when he took off from Augsburg.

Hess in British Custody

On Sunday, May 11, the Nazis with Hitler at his Alpine retreat in Obersalzburg had no idea how to spin the story. Hess had flown the coop, seemingly to negotiate peace in England, but there was no word of his fate. The next day, a brief statement was issued. Hitler had consulted only with Otto Dietrich, his press chief, who was at Obersalzburg, but not his public relations guru, Joseph Goebbels, Minister of Propaganda and Popular Enlightenment, who was not present. The communiqué mentioned “mental derangement,” described Hess as the “victim of hallucinations,” and concluded (hopefully) that he must have crashed. Goebbels dismissed the immediate response as amateurish. “It’s rightly asked how such an idiot could be the second man after the Führer,” he remarked while noting in his diary, “What a spectacle for the world: a mentally-deranged second man after the Führer.”

On May 13, the BBC announced that Hess was in British custody and, consequently, the German story had to change. By this point, Goebbels had gotten control of the German messaging, and explanations ceased following a final communiqué that evening. It asserted that Hess’s “mental distraction” was a very recent phenomenon brought on by overwork and the stress of his party responsibilities. It also held open the possibility that “Hess was deliberately lured into a trap by a British party.” Afterward, Goebbels repeatedly asserted in his diary that the affair was over.

Reports from party officials and public opinion research indicated otherwise. Particularly concerning to Goebbels was the fact that Hess had become a topic for humor: “The 1,000-year Reich is now the 100-year Reich because one zero is gone.” Goebbels had a potential public relations disaster on his hands.

While the Germans were struggling to get their messaging straight, London was also trying to understand what was going on and what should be done. The delayed and muted British response after the initial, terse communiqué followed from two discrete issues. From the get-go, the British were unsure of Hess’s competence. Churchill dismissed him as “a disordered mind” who behaved like “a mentally defective child who has been guilty of murder or arson.” His British psychiatrist, Dr. J.R. Rees, opined, “Hess is a man of unstable mentality and has most certainly been like that since adolescence.” If Hess was mentally ill, he might be unstable, unpredictable, and potentially damaging if attempts were made to use him for propaganda purposes.

This conundrum arose amid a bureaucratic free for all that virtually paralyzed the British response. It was an open question as to who controlled propaganda, psychological warfare, and the use of an asset like a captive deputy Führer. The Ministry of Information (MOI) claimed, not surprisingly, that Hess was a propaganda tool and hence in their purview. The Foreign Office (FO) insisted that this was a diplomatic issue and was clearly their responsibility. The Special Operations Executive (SOE), responsible for black ops and resistance in occupied Europe, also put in a claim. Finally, Lord Beaverbrook injected himself into the mix because he was a friend of Churchill’s, owned much of Fleet Street, and had been heavily involved in British propaganda efforts in World War I.

The net result, clearly apparent to Goebbels as his diary reveals, was that England had missed a splendid opportunity to stick it to the Reich. On May 16, he wrote, “We are dealing with dumb amateurs over there. What we would do if the situation were reversed!” Three days later he continued, “London has missed a big chance…. Hess is already scrap iron so far as London is concerned.” Goebbels realized that only British hesitancy had saved Germany from a public relations disaster.

Despite Hess’s ongoing insistence that his peace proposals were real and relevant, he largely disappeared into the tight circle of his guards and doctors for the five years following his fantastic voyage. This did not stop him from composing long memoranda entitled “Peace Proposals,” including one that he demanded to have forwarded to the duke in the fall of 1941. Despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary, Hess persisted in the belief that he was an important and influential diplomatic emissary. This unlikely assumption speaks volumes about his divorce from reality.

Hess at the Nuremberg Trials: “Hess looks crazy now. The sickest man one ever saw.”

When Hess returned to the public eye as an accused war criminal at the Nuremberg trials, his bizarre behavior and even stranger continuing fervor for his dead Führer marked him apart from the other defendants. The court psychiatrists only questioned the sanity of two defendants: Hess and the sadistic, rabidly anti-Semitic Julius Streicher. Ultimately, both were deemed fit to stand trial.

The British official artist Dame Laura Knight thought otherwise. “Hess looks crazy now. The sickest man one ever saw. Born to burn at any stake for any cause that happens along…. The eyes of a fanatic, cavernous in that emaciated, grey-white face.” His final address to the court only confirmed his continued commitment. He concluded, “I am happy to know that I have done my duty to my people, my duty as a German, as a National Socialist, as a loyal follower of my Führer. I do not regret anything.” Unrepentant, he was a true believer to the bitter end.

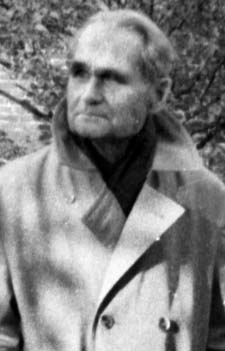

Hess was found not guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity. Convicted only of crimes against peace and conspiracy, he was sentenced to life imprisonment and transferred with the other convicted war criminals spared execution to Spandau Prison in Berlin. On September 29, 1966, architect Albert Speer and Baldur von Schirach, former Hitlerjugend leader and gauleiter, were released, leaving Hess the sole remaining prisoner, effectively condemned to solitary confinement. Despite repeated efforts by family, other interested parties, and Western governments, the Soviets vetoed any suggestions that Hess be released. Aged (he turned 80 in 1974), imprisoned alone, increasingly infirm, and only occasionally considered newsworthy on the anniversary of his flight, Hess faded from public consciousness during the 1970s.

The Murder of Rudolf Hess: How Did He Die?

In 1979, he burst back into the headlines with the publication of The Murder of Rudolf Hess. Former British Army doctor Hugh Thomas, who had examined Hess, asserted that the prisoner in Spandau could not be Hess. He assembled circumstantial evidence. The flight exceeded the range of the Messerschmitt Me-110 aircraft the pilot had flown, the prisoner refused to see his family for more than 35 years, and there was also additional “best evidence” of a medical sort. Hess was wounded in the chest during World War I, yet the prisoner had no scars, according to Thomas. It was seemingly irrefutable evidence that the prisoner in Spandau was not Rudolf Hess.

Regardless of the identity of the prisoner, he was found dead on Monday, August 17, 1987, in the summer house in the prison garden. Officially, it was ruled a suicide. Medical records, however, suggest that he was too infirm to have hanged himself, and his nurse that day concurred. The nurse also attested that unknown men in U.S. Army uniforms were present at the scene. His son, Wolf Rutiger, personally commissioned a second autopsy that concluded the cause of death was “the application of force to the neck by a cord form of instrument,” or strangulation in laymen’s terms. Rumors persist that the prisoner was murdered to prevent him from publicizing embarrassing details of wartime secrets or his real identity as a doppelganger, were he to be released on compassionate grounds before he died.

Hess was buried in the family plot in the Bavarian town of Wunsiedel. The grave attracted neo-Nazi demonstrations, causing the local Lutheran church council to refuse to extend the lease on the plot. As a result, the bones were exhumed at dawn on July 21, 2011, and cremated, the ashes scattered at sea. Many questions remained, but answers to the Rudolf Hess enigma seemed lost forever.

While the circumstances surrounding Hess’s death remain in dispute, the doppelganger theory was categorically disproved in January 2018. Forensic DNA research established that “the conspiracy theory claiming that prisoner ‘Spandau #7’ [Hess] was an imposter is extremely unlikely, and therefore disproved.” Fortuitously, a slide of a blood sample taken from Hess in December 1982 had been preserved and came to the awareness of Colonel (Dr.) Sherman McColl while he was doing a residency at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. Realizing it might provide DNA evidence to resolve the doppelganger controversy, McColl contacted Jan Cemper-Kiesslich at the University of Salzburg’s Interfaculty Department of Legal Medicine. He explained the complicated and sensitive questions surrounding selecting a lab, saying, “For the result to have most credibility it needed to come from an official forensic genetics lab. In case the result was controversial, it would best be performed outside Germany or the four powers. It was an advantage to have native German speakers, which left Austria. As for Salzburg, the chairman was one of the four pathologists on the second Hess autopsy and enjoyed the confidence of the family.”

Cemper-Kiesslich explained by e-mail that he became interested in “the application of forensic DNA testing in the course of archaeological and historical research” as a student. His work has covered “Roman and medieval times, reliquaries and the remains of holy men, historical family and noblemen’s graves.”

With regard to Rudolf Hess, based on comparison with an anonymous but verified male relative, the conclusion is unequivocal. “Prisoner ‘Spandau #7’ indeed was Rudolf Hess, the deputy Führer of the Third Reich. Hence, the conspiracy theory claiming that prisoner ‘Spandau #7’ was an imposter is extremely unlikely, and therefore disproved” [emphasis in the original].

The man that died in Spandau was Rudolf Hess, although the cause and circumstances of his death remain unclear. This has been conclusively proven, although a host of other questions about Hess’s life remain. Fittingly, Hess spent his incarceration in England at Camp Z near Aldershot, only a few miles from Ockham, birthplace of philosopher and Franciscan friar William of Ockham, whose most important contribution to science and philosophy was his insistence that, barring evidence to the contrary, the simplest explanation is most likely to be correct.

In this vein, the final word belongs to 2nd Lt. M. Loftus, a guard whom Hess grew to trust during his imprisonment at Aldershot. According to Loftus, Hess was “one of the simplest men you could meet,” dedicated to one and only one purpose, a “single-tracked, blind, and fanatical devotion to an ideal and the man [Hitler] who is his leader.”

Author Bob Gordon recently wrote for WWII History on the M-29 Weasel. He resides in Brantford, Ontario, Canada.