By Michael E. Haskew

The bloody fight for Guadalcanal, where the string of Japanese conquests in the Pacific had finally run its course, was a turning point of World War II. Still, the long island road to Tokyo Bay would require fighting a tenacious foe across desolate islands, through jungles, and over vast stretches of ocean for more than three more years.

The beginning of the American offensive in the Solomon Islands heralded a grand, new strategy that would accomplish three goals. First, seizing Guadalcanal, Tulagi, and the Santa Cruz Islands would provide a springboard for further operations up the Solomons chain. Second, capturing the northeastern coast of New Guinea and the Central Solomons would provide bases and logistical support for the most ambitious and significant of the three objectives. The neutralization of the Japanese supply base at Rabaul on the eastern coast of the island of New Britain in the Bismarcks was necessary for the success of future Allied operations.

The Japanese had occupied New Britain in February 1942 and established their principal forward base in the region at Rabaul. Simpson Harbor was a superb natural anchorage for Japanese naval vessels operating in the Solomons, and aircraft flying from bases at Rabaul threatened the American effort on Guadalcanal. Japanese planes were also poised to attack supply and troop convoys and potentially sever lines of communication with Australia and New Zealand.

Rabaul also served as a shield for the vast Japanese bastion at Truk in the Caroline Islands. As long as Rabaul remained operational and in Japanese hands, American progress toward the Philippines and the Central Pacific was seriously hindered.

In the summer of 1942, the American joint chiefs of staff issued a strategic directive targeting Rabaul and describing the proposed three-stage reduction of the base. General Douglas MacArthur, the commander in chief of the Southwest Pacific Area, had previously devised the Elkton Plan as a strategic template for the neutralization of Rabaul. Naval planners added a methodology, and the early versions of the Elkton Plan evolved into a strategic initiative codenamed Operation Cartwheel. The remaining two phases of Cartwheel came under MacArthur’s command after Guadalcanal was captured. Naval and Marine forces in the region were under the command of Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey, who took charge of the tactical planning for the reduction of Rabaul.

“Rabaul, a Japanese naval and air stronghold, appeared at this time to be the logical objective towards whose seizure or neutralization all efforts of both the South and Southwest Pacific Forces would be directed,” commented Halsey, grasping the strategic implications of the pending Operation Cartwheel. “Until Rabaul was seized, or at least naval and air control of the New Britain area was established, the planned advance of the Southwest Pacific Forces along the New Guinea coast was impracticable.”

The Cartwheel manifesto originally identified 13 distinct operations. On closer inspection, it was determined that its goals could be accomplished with only 10. Three objectives—Kavieng at the northern tip of New Ireland, the island of Kolombangara, and Rabaul itself—were deemed too heavily defended and costly to undertake. These would be bypassed and left to literally wither on the vine as American forces advanced.

To sustain their momentum following the victory at Guadalcanal, senior American military planners wasted no time putting the pieces of Cartwheel together. In late February 1943, the 3rd Raider Battalion and Army troops from the 43rd Infantry Division landed unopposed, taking control of the Russell Islands. On June 30, the 1st and 4th Raider Battalions, the 9th Defense Battalion, a tank platoon of the 10th Defense Battalion, Marine Air Group 22 (MAG-22), and elements of the Army’s 43rd Infantry Division began landing and air operations against the Japanese on the island of New Georgia, 200 miles north of Guadalcanal. The 12th Defense Battalion and Army units including the 112th Cavalry Regiment and the 158th Regimental Combat Team occupied the Trobriand and Woodlark Islands in conjunction with landings on New Guinea.

The 4th Raider Battalion took Segi Point on New Georgia and marched to secure Viru Harbor on July 1. Navy Seabees (Construction Battalions) moved in to construct an airfield. By the end of July, Army and Navy fighter and bomber squadrons were operational. The primary objective of the New Georgia operation was the airfield at Munda, and on August 5, Army troops and Marines captured it, following six weeks of stubborn Japanese resistance. Marine Raiders and elements of the 148th Infantry Regiment attacked the enemy barge base at Bairoko on July 20, but the defenders held out until the end of August, by which point the Japanese had determined they could not hold indefinitely and evacuated New Georgia.

The island of Vella Lavella was captured by 25th Infantry Division troops and soldiers of the 3rd New Zealand Division on September 3, and 10,000 Japanese troops were cut off and bypassed on Kolombangara. The Japanese effort to evacuate their remaining forces in the Central Solomons was a difficult undertaking, as the U.S. Navy sank a number of transports and contested the withdrawal. By the end of October, American air power was conducting daily raids on Rabaul. American aircraft from Guadalcanal, New Georgia, and Vella Lavella began pounding the base, and dogfights involving large numbers of planes were daily occurrences.

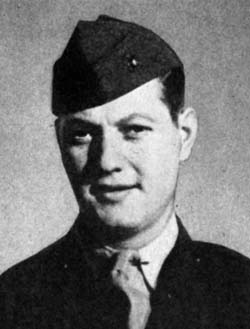

Operating from Henderson Field on Guadalcanal on April 7, 1943, 22-year-old VMF-221 pilot Lieutenant James E. Swett led a division of four Marine F4F Wildcat fighters on patrol over the Russell Islands. It was his first combat mission, and Swett spotted 15 Japanese Aichi D3A Val dive bombers flying in formation. He ordered the other Wildcat pilots to follow and swept in to attack. Swiftly, he flamed three of the enemy planes, cleared the scattering enemy formation, and attacked a second group of six Vals, shooting down another and then damaging a fifth.

Swett was credited with seven aerial victories during the single mission and received the Medal of Honor. His Wildcat was damaged by both the rear machine gunners in the Vals and friendly antiaircraft fire, forcing Swett to ditch in the waters off Tulagi. He returned to duty and later qualified to fly the new Vought F4U Corsair fighter, well known for its gull-wing construction and feared by the Japanese who nicknamed it “Whistling Death.” Swett met with further success as VMF-221 transitioned to the powerful aircraft. He finished the war with 15.5 confirmed kills and four probable kills, retired from the Marine Corps in 1970 with the rank of colonel, and died in 2009 at the age of 88.

As the air war in the Solomons intensified, the Japanese committed at least 700 planes to the campaign during five months of fighting from June to October 1943, and many of these were shot down by American pilots.

A breakdown of the Japanese command structure was laid bare at this juncture. Without unity of command, the Japanese Army and Navy failed to coordinate their efforts. Japanese forces were now decidedly on the defensive. In the end, it was clear to Imperial General Headquarters that their defensive perimeter would inevitably contract. All efforts were to be made to slow the American advance toward their obvious target, Bougainville in the Northern Solomons astride the Allied axis of advance toward Rabaul. Japanese senior commanders were also painfully aware that the effectiveness of Rabaul as a forward base was eroding with each passing day.

Considering the new reality of American successes in the Solomons and New Guinea, the Japanese began modifying their defense in the South and Central Pacific. The principal line of resistance in the late summer of 1943 became the Caroline and Mariana island groups. Thus, the Imperial Japanese Navy was not to commit major resources in further defensive efforts in the Solomons.

In addition to its proximity to New Britain and Rabaul, Bougainville was also the center of Japanese troop strength in the Northern Solomons, particularly since troops evacuated from other islands during the previous months had been concentrated there. Lt. Gen. Haruyoshi Hyakutake, who had been defeated on Guadalcanal months earlier, commanded the 17th Army at Bougainville. Including the 6th Division, his most effective combat troops, Hyakutake’s peak troop strength on Bougainville was estimated at more than 45,000.

With the completion of ground operations in the Central Solomons during the first week of October, Allied efforts then concentrated on the upcoming landings on Bougainville. The date for the invasion of the island, codenamed Operation Cherry Blossom, was set for November 1, 1943. The invasion plan was modified several times during the weeks leading up to the landings. Empress Augusta Bay was chosen as the Marine landing site because of its distance from the bulk of the island’s Japanese defenders. The closest were at least 25 miles away. The area also provided a good location for a radar station and PT-boat (patrol torpedo) base.

Senior American commanders deemed it unnecessary to capture all of Bougainville. The seizure of enough ground to construct an airfield that could accommodate shorter range light and medium bombers and fighters for striking Rabaul would be sufficient.

Although the Bougainville landings were the primary thrust of the renewed offensive, secondary operations were mounted in the Treasury Islands, southeast of Bougainville at the island of Choiseul, and in the Green Islands in February 1944. Combined with air superiority in the vicinity, these landings were intended as diversions to the main operation at Bougainville and to cut the supply lines in and out of Rabaul, contributing to the containment of the garrison until the end of the war.

Major General Alexander A. Vandegrift, who had performed brilliantly in command of the American forces on Guadalcanal, was to lead the I Marine Amphibious Corps (IMAC) in the effort in the Northern Solomons. IMAC included the 3rd Marine Division under Maj. Gen. Allen H. Turnage, the 2nd Marine Raider Regiment, and the 1st Marine Parachute Regiment. Its reserve element was the Army’s 37th Infantry Division. Vandegrift had been on his way to Washington, D.C., to assume the post of commandant of the Marine Corps when the sudden death of IMAC commander Maj. Gen. Charles D. Barrett necessitated his return to the combat zone. Vandegrift held the IMAC command until November 9, when he was relieved by Maj. Gen. Roy Geiger.

The landing beaches at Empress Augusta Bay stretched approximately 8,000 yards from Cape Torokina in the east to Koromokina Lagoon in the west. They were divided into 11 sections identified by a color. A 12th landing was scheduled on nearby Puruata Island just offshore. The 9th Marines, commanded by Colonel Edward A. Craig, and Lt. Col. Fred E. Bean’s 3rd Raider Battalion were responsible for the five beaches on the left along with Puruata, while the 2nd Raider Regiment minus one battalion, under Colonel Alan Shapley, and the 3rd Marine Regiment, commanded by Colonel George W. McHenry, were to assault the six beaches to the right.

Before dawn on November 1, naval gunfire opened the Marine effort to secure Bougainville. Shells screamed overhead while men ate their breakfast and clambered onto the decks of their transports. When the order was passed at 7:10 am, 7,500 Marines climbed down nets and into waiting Higgins boats for the 5,000-yard run to the beaches.

The first wave of landing craft fought heavy surf to reach the shoreline slightly ahead of schedule. The following waves, however, encountered serious difficulties as substantial swells tossed them into one another, throwing them off course. A number of boats were emptied on the wrong beaches, and three of the originally approved sites were abandoned as unusable. Amid the chaos, one company of the 3rd Marines ran a gauntlet of enemy fire, filtering through the zones of two other formations before reaching its assigned position.

The 9th Marines encountered little resistance, but the 3rd Marines took heavy fire from Japanese machine-gun and mortar emplacements along with a single 75mm gun at Cape Torokina. Fourteen landing craft were destroyed, and among the casualties were Major Leonard M. “Spike” Mason, commander of the 1st Battalion, 3rd Marines, and Lt. Col. Joseph McCaffery, executive officer of the 2nd Raider Regiment, who later died of his wounds.

For more than an hour, the Marines were pinned down on the beaches or took shelter in shell craters along the edges. Then, Sergeant Robert A. Owens, ignoring a serious wound, rose up and charged the bunker that housed the troublesome 75mm gun. He killed its crew but was fatally wounded in the action. Owens received a posthumous Medal of Honor for his act of courage. Elsewhere, individual Marines got moving and gained the upper hand against the defenders. As they moved inland to their initial objectives up to 1,000 yards from the shore, it became apparent that the naval bombardment had caused little or no damage to enemy strongpoints.

The Marines unloaded supplies as the sun rose, and the guns of the 12th Marine Artillery were hauled ashore. Japanese troops continued to harass the landing beaches, and enemy planes appeared overhead. An aerial melee resulted in the downing of 26 Japanese aircraft. Meanwhile, five Marines of a reinforced company of the 3rd Battalion, 2nd Raiders were killed fighting stubborn Japanese troops at Puruata Island, which was secured on November 3.

A Japanese naval force sailed from Simpson Harbor with orders to destroy the American ships off Bougainville, and during the night of November 1-2, the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay ended the threat with a decisive American victory. The Japanese lost a light cruiser and a destroyer sunk, a heavy cruiser, light cruiser, and two destroyers damaged, and 25 aircraft shot down. The Americans suffered damage to a light cruiser and a destroyer.

Although their perimeter on Bougainville was becoming well established, the Marines prepared for inevitable enemy counterattacks. They worked for a week to consolidate the beachhead and fought periodic skirmishes with the Japanese. On November 7, an enemy landing was spotted to the west between Koromokina Lagoon and the Laruma River. The landing craft were similar in construction to those used by the Americans, and one Marine antitank gun held its fire for a time as landing craft carrying 475 Japanese soldiers approached.

When the Japanese landing cut off a group of Marines, Pfc. John F. Perella swam 1,000 yards to retrieve a rescue boat that delivered his unit to safety. He received the Silver Star for his heroism. More than 30 Japanese soldiers were killed when Marines under Lt. Col. Walter Asmuth, commander of the 3rd Battalion, 9th Marines, led a company-sized assault against the enemy and called in devastating howitzer fire from the guns of the 12th Marines artillery.

The Japanese persisted, some of them yelling in English, “Marine, you die!” and the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines relieved the beleaguered 3rd Battalion just after 1 pm. During the night, Japanese soldiers infiltrated through the Marine perimeter, firing their rifles into the tents where doctors of the 3rd Medical Battalion were tending wounded men. Rear echelon Marines, including cooks and clerks, were pressed into security service, validating the assertion that every Marine is a rifleman first.

On November 8, elements of the 21st Marines had reached positions to take the offensive. Lt. Col. Ernest W. Fry’s 1st Battalion stepped off with light tanks in support, following a heavy artillery and mortar barrage. Fry unleashed his Marines in an area 300 yards wide by 600 yards deep. They advanced steadily against sporadic resistance. The preliminary bombardment had literally shattered the Japanese, blowing some men to pieces and flinging bodies into nearby trees. The bodies of more than 250 dead Japanese littered the area. During the desperate fighting of November 7-9, two Marines, Sergeant Herbert J. Thomas of the 3rd Marines and Pfc. Henry Gurke of the 3rd Raider Battalion, earned posthumous Medals of Honor after smothering live hand grenades with their own bodies to shield comrades.

Simultaneously, Marines of the 2nd Raider Regiment established a roadblock along the Piva Trail. These Marines were reinforced by other troops from the 2nd Raiders and the weapons company of the 9th Marines. An order to advance to the junction of the Piva and Numa-Numa Trails was issued, but before the Marines could move forward, the Japanese hit them hard. Hand-to-hand fighting and accurate Marine artillery fire left 550 Japanese soldiers dead.

By mid-November, the Army’s 129th, 145th, and 148th Infantry Regiments, 37th Infantry Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Robert S. Beightler, were ashore on Bougainville along with three Army field artillery battalions and their 105mm howitzers. On the 11th, a combined Marine-Army offensive went forward to seize a critical crossroads along the Numa-Numa Trail. When the Japanese sprang an ambush, the 21st Marines were locked in a vicious fight and called in air support from Marine bombers. The trail junction was secured in what became known as the Coconut Grove Battle, and the beachhead advanced another 1,500 yards in some areas.

During the last week of November, the pivotal Battle of Piva Forks led to the destruction of an entire Japanese infantry regiment. Marine patrols discovered an enemy roadblock along the East-West Trail between the two forks of the Piva River, and when elements of the 3rd Battalion, 3rd Marines had dispersed the enemy defenders, they established a roadblock of their own. A patrol then occupied the summit of a 400-foot-high ridge with commanding views of the surrounding terrain all the way to Empress Augusta Bay.

For the next four days, 1st Lt. Steve J. Cibik and a few battle-hardened Marines fought off repeated Japanese charges against the ridge’s crest. The Marines held, and Cibik received the Silver Star. The high ground was renamed in his honor as Cibik Ridge.

The rest of the 3rd Marines continued to advance. With Marine Raiders and elements of the 21st Marines and the 37th Division in support, they encountered heavy resistance, but they maintained the initiative. After falling back briefly, one Marine unit positioned a machine gun to deter further Japanese attacks. The weapon cut down 74 of 75 enemy soldiers that approached to within 30 yards. Marine patrols regularly got the drop on unsuspecting Japanese troops. One mowed down scores of the enemy as they milled about nonchalantly in a chow line.

The Marines fought the Japanese and the debilitating jungle conditions, driving the defenders from objectives their commanders labeled with the phonetic alphabet, such as Dog, Easy, and Fox. By November 23, the Americans had detected a strong line of resistance with at least 1,200 Japanese defenders in place. Artillery observers on Cibik Ridge registered their weapons, and an impressive array of heavy guns was assembled nearly wheel hub to wheel hub as the Marines prepared to cross the Piva River for the assault.

At 8:35 the next morning, Thanksgiving Day, the artillery began barking incessantly. The field guns included 155mm, 105mm, and 90mm antiaircraft weapons of both the Army and the 12th Marines. Forty-four Marine machine guns began chattering. As the American heavy weapons fired 5,600 rounds at the positions occupied by the Japanese 23rd Infantry Regiment, the enemy artillery replied.

Major Donald M. Schmuck, a company commander in the 3rd Marines, remembered, “For 500 yards, the Marines moved in a macabre world of splintered trees and burned-out brush. The very earth was a churned mass of mud and human bodies. The filthy, stinking streams were cesspools of blasted corpses. Over all hung the stench of decaying flesh and powder and smoke which revolted the toughest. The first line of strong points with their grisly occupants was overrun and the 500-yard phase line was reached.”

Schmuck continued, “The Japanese were not through. As the Marines moved forward, a Nambu machine gun stuttered and the enemy artillery roared, raking the Marine line. A Japanese counterattack hit the Marines’ left flank. It was hand-to-hand and tree-to-tree. One company alone suffered 50 casualties, including all its officers. Still the Marines drove forward, finally halting 1,150 yards from their jump-off point, where resistance suddenly ended. The Japanese 23rd Infantry had been totally destroyed, with 1,107 men dead on the field. The Marines had incurred 115 dead and wounded. The battle for Piva Forks had ended with a dramatic, hard-fought victory which had ‘broken the back of organized enemy resistance.’”

More Marine units entered the offensive, steadily stoking the momentum. On November 25, elements of the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines charged a small knoll that was known as Hand Grenade Hill from that day forward. The Marines reached within 50 yards of positions held by about 70 Japanese soldiers, who tenaciously refused to retreat and threw grenade after grenade at the Americans. In the gathering darkness, the enemy then melted into the jungle.

The anticipated limit of the previously established American defensive perimeter on Bougainville was within the Marine and Army troops’ grasp as November waned. Two thousand yards distant, near the spot where the East-West Trail crossed the Torokina River, a group of hills had to be taken to consolidate the perimeter. Hill 1000 was the focus of the Marine attack spearheaded by the 1st Parachute Regiment. A spur of this high ground soon came to be known as Hellzapoppin’ Ridge. With the help of three other Marine regiments, Major Robert Vance led his parachutists, who fought as ground troops, in capturing Hill 1000 on December 5.

Vance attacked the spur on December 9 and made little headway. The next day, two battalions of the 21st Marines and a supporting battalion of the 9th Marines renewed the attack. Brutal fighting raged for six more days. Dozens of Marines were killed or wounded. The bodies of the parachutists lay exposed for a time, serving as constant reminders to the ground troops of the tenacity of the Japanese defenders.

While the battle swirled on Hellzapoppin’ Ridge, one of the primary objectives of the Marine presence on Bougainville was realized and began to pay a huge dividend. Corsair fighters of VMF-216, the vanguard of an aerial onslaught and the command known as Air Solomons that would ravage Rabaul, had reached the operational airstrip at Torokina on December 10. Marine planes roared in on Hellzapoppin’ Ridge and dropped 100-pound bombs, some of them exploding a mere 75 yards from Marine positions. The Marine pilots flew repeated sorties for several days. The aerial bombardment was followed by a shower of 155mm artillery shells from Army howitzers set up near the mouth of the Torokina.

Finally, on December 18, two battalions of the 21st Marines advanced from Hill 1000 and executed a double envelopment of Hellzapoppin’ Ridge. Those enemy soldiers who had survived the heavy Marine pounding of the preceding days were too stunned to offer much resistance. A Marine combat correspondent related, “No one knows how many Japs were killed. Some 30 bodies were found. Another dozen might have been put together from arms, legs, and torsos. The 21st suffered 12 killed and 23 wounded.”

For five more days, the 3rd Marine Division fought to ferret enemy defenders out of holes and bunkers along the remaining high ground around Hill 1000. On Christmas Day, the Marines found the remaining Japanese positions abandoned.

With their mission on Bougainville accomplished, tired Marines, some of whom had spent nearly two months in the line, were withdrawn from Bougainville. The 3rd Marine Regiment departed on Christmas Day, followed by the 9th Marines on December 28, and the 21st Marines on January 9, 1944. Marine casualties on Bougainville amounted to 423 dead and 1,418 wounded. Estimates of the casualties they inflicted on the Japanese ran as high as 2,500.

After the withdrawal of the 3rd Marine Division, the Army’s 37th and Americal Divisions took over on Bougainville. At first, only occasional Japanese resistance was encountered. In late February and early March 1944, though, a sizable enemy offensive was defeated on the island. From November 1944 through the end of the war, the Allied presence on Bougainville was an Australian affair. The II Corps, commanded by Lt. Gen. Sir Stanley Savige, conducted operations against a Japanese presence on the island that still numbered approximately 40,000 troops.

By the time World War II in the Pacific ended, Rabaul was an operational backwater. The Japanese on New Britain did not surrender until they received notification that the war was over. The tough campaign waged by the Marines of the 3rd Division in 1943, however, had long ago made their presence irrelevant.

On December 26, 1943, a year after their long fight to take Guadalcanal ended in a major victory, the Marines of the 1st Division, now under Maj. Gen. William H. Rupertus, were again on the offensive.

After rest, recuperation, and assimilating replacements, the 1st Division was hitting the two “Yellow” beaches at Cape Gloucester on the western end of the island of New Britain, 300 miles away from the major Japanese base at Rabaul. Troops of the Army’s 112th Cavalry Regiment had made a diversionary landing at Cape Merkus two weeks earlier.

The Marine objective was control of the Japanese airfield complex at Tuluvu. General Douglas MacArthur, commander in chief of the Southwest Pacific Area, wanted the complex for several reasons. Chief among them were the possibility of Allied airstrikes that could be launched against Rabaul in preparation for a potential direct assault on the enemy base, as well as the strategic location of Cape Gloucester near the Dampier Strait, which Allied shipping would have to transit as MacArthur made subsequent offensive moves toward the Philippines.

After Operation Cartwheel was altered to strangle Rabaul rather than to capture the base by direct assault, MacArthur still believed that taking the two airfields at Tuluvu would allow aircraft to tighten the noose around the enemy bastion. Some historians, however, have criticized the Cape Gloucester operation as unnecessary.

More than 10,000 Japanese troops defended western New Britain. These were under the command of Maj. Gen. Iwao Matsuda and consisted of elements of the 65th Infantry Brigade, 51st Division, and the 1st and 8th Shipping Regiments. About 7,500 troops were defending the vicinity of Cape Gloucester.

After difficult landings on the narrow beaches due to rough surf that buffeted their landing craft, two battalions of the 7th Marines moved inland. They initially encountered more resistance from the difficult terrain than the Japanese. In a single day, a total of 13,000 troops and more than 7,500 tons of supplies came ashore. Air Solomons provided fighter cover, while bombers hit visible targets.

Supported by tanks and artillery, the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 5th Marines took the airfields on December 30. Heavy rains slowed further operations, but by mid-January surrounding high ground was in Marine hands. The 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines seized Hill 660 and held it against subsequent Japanese counterattacks.

The 1st Marine Division consolidated its hold in western New Britain during the coming days and succeeded in driving the Japanese from the area before withdrawing in two echelons during the first week of April and in early May. Troops of the Army’s 40th Infantry Division moved in to replace them.

For the Japanese defenders in western New Britain, the cost was high: 3,100 killed and wounded. Marine casualties were 248 killed and 772 wounded.

With the success of Operation Cartwheel, the American momentum in the Pacific was sustained. The great victory at Guadalcanal was consolidated, and the might of U.S. industry and manpower were beginning to wear the enemy down with telling effect. However, much difficult and costly fighting lay ahead in the Pacific Theater.

Michael E. Haskew is the editor of WWII History magazine. He has authored numerous books and magazine articles during more than 35 years as a historian. He resides in Chattanooga, Tennessee.