By David A. Norris

The U.S. cavalrymen posted at Fort Laramie in the Dakota Territory on Christmas Day 1866 celebrated the holiday with a full dress garrison ball despite subzero temperatures and more than a foot of snow on the ground. While Captain David S. Gordon of the 2nd U.S. Cavalry was mulling over whom he would choose as his next dance partner at 11 pm, a stranger wearing a heavy buffalo overcoat, pants, gauntlets, and cap burst into the ballroom.

Scout John “Portugee” Philips contrasted sharply with the soldiers in their military dress uniforms and the women in their Victorian finery. Brig. Gen. Innis Palmer summoned Gordon to the post headquarters and handed him the dispatch that Philips had carried for four days on his 236-mile ride during which he endured blizzard conditions. The dispatch from Colonel Henry B. Carrington at Fort Phil Kearny stated that three officers, 92 men, and two citizens had been massacred four days earlier near the fort. The utter destruction of the detachment, commanded by Captain William J. Fetterman, was the worst disaster to befall the U.S. Army up to that point in the Indian Wars of the 19th century.

Fort Phil Kearny sat precariously on land that was ceded by the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851. Signed by the United States and eight Indian nations, the treaty set aside parts of Nebraska, South Dakota, Montana, and Wyoming as exclusively Indian land. The U.S. Army was permitted to build forts within the treaty lands; other white intruders were forbidden.

Peace lasted until August 19, 1854, when Lieutenant John Lawrence Grattan led 30 soldiers into a Brule and Oglala Sioux village. Grattan was there because a settler complained that a Sioux named High Forehead had stolen a cow. High Forehead had simply butchered a cow whose owner had abandoned the animal because it was lame. The lieutenant’s aggressive manner ignited a quick battle in which Grattan and all of his men were killed. The incident, called the Grattan Massacre by the Army and settlers, sparked the First Sioux War.

Fighting ended in 1856. A few years of relative peace followed, although white buffalo hunters and trappers poached within the treaty lands. Conflict flared again after a promising gold strike at Alder Gulch in 1862 spurred the creation of the legendary Montana boom town of Virginia City. Despite the bloodshed in the East during the second year of the Civil War, the temptation of quick riches lured a veritable stampede of gold seekers toward Virginia City.

Avoiding the Laramie Treaty lands required long detours for travelers. Seeking a quicker path to the gold fields, frontiersmen John M. Bozeman and John Jacobs blazed a route known as the Bozeman Trail in 1863. Leaving the Oregon Trail near the North Platte River northwest of Fort Laramie, the 680-mile-long Bozeman Trail was the shortest possible route to the gold mines.

But the Bozeman Trail crossed the Powder and Tongue Rivers, slashing through the heart of the lands set aside for the Indians after the 1851 treaty. These were the richest hunting grounds left to the tribes. Deer, elk, and mountain sheep were plentiful. Wagon trains disrupted the hunting, and draft animals and livestock ate up great swaths of grassland. The Indians attacked most of the wagon trains that cut through the treaty lands.

Retaliating for an 1862 uprising in Minnesota, Brig. Gen. Alfred Sully campaigned against the Sioux in 1863 and 1864. In 1864 Sully’s 4,000 troops destroyed tipis, horses, clothing, blankets, and food supplies. As a result, the Sioux were left to face the harsh winter empty handed. Several hundred miles away, Union volunteer troops killed 150 people in an unprovoked attack on a Northern Cheyenne and Northern Arapaho village at Sand Creek in the Colorado Territory on November 29, 1864.

The Sully expeditions and Sand Creek Massacre pushed Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapahoe bands into the North Platte River country. They had ample opportunity for revenge by attacking wagon trains on the busy emigrant routes. In August 1865, Brig. Gen. Patrick E. Connor began building Fort Reno inside the Laramie Treaty lands to protect Montana-bound wagon trains on the Bozeman Trail.

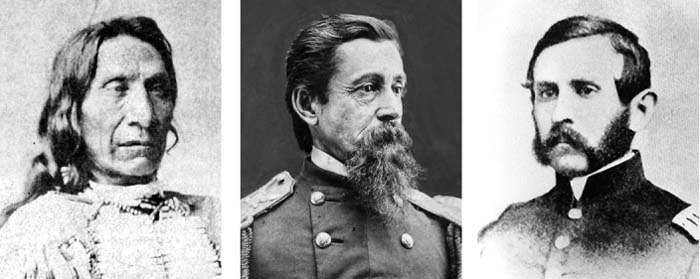

Major General Philip St. George Cooke took command of the Department of the Platte in 1866. Cooke, who was the father-in-law of the late Confederate Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, was a veteran of the Indian Wars. Cooke had served as a cavalry commander during the Peninsula Campaign and Seven Days Battles, but the awkwardness of his ties to Stuart compelled him to resign active service. After the war President Andrew Johnson nominated Cooke for appointment to the brevet grade of major general in the Regular Army.

Cooke’s General Orders No. 33, issued on March 10, authorized construction of two more posts along the Bozeman Trail. The order also designated the trail’s section of the Department of the Platte as the Mountain District. Command of the new district went to Carrington, who had been a successful lawyer in Ohio before the Civil War. Although appointed colonel of the new 18th U.S. Infantry, Carrington did not serve in the field. He wound up being transferred from one administrative duty to another during the war.

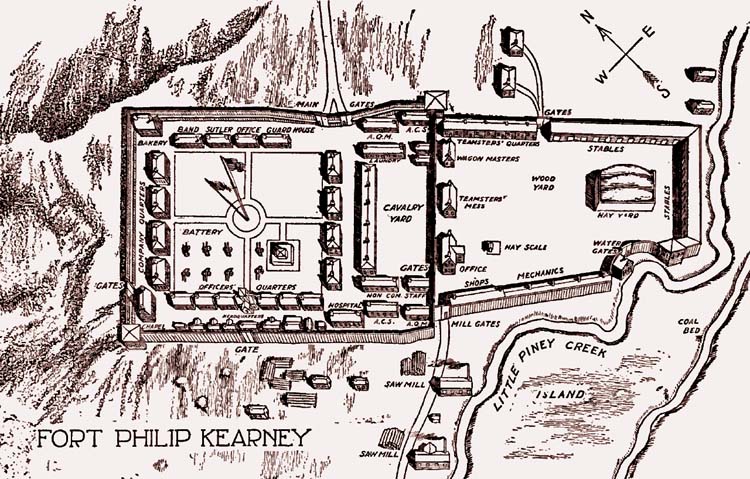

Carrington arrived at Fort Reno in June with 700 men of the 18th U.S. Infantry. Approximately 500 of them were new recruits, and there were only a dozen officers with them. He soon chose a site on Big Piney Creek, a tributary of the Powder River, which became Fort Phil Kearny. Carrington also chose a site overlooking the Bighorn River in Montana to build a third post on the trail, Fort C.F. Smith.

Not to be confused with Fort Kearny in the Nebraska Territory, which was established in 1848 and named for the famous frontier officer Brig. Gen. Stephen Watts Kearny, the new post was named for Maj. Gen. Philip Kearny, who was killed in action at the Battle of Chantilly on September 1, 1862.

Fort Phil Kearny was the largest of the Bozeman Trail posts. The original stockade was built of foot-thick logs, each 11 feet long and buried three feet into the ground. The original log walls, 600 feet by 800 feet long, enclosed more than 11 acres and about 40 buildings. Two sawmills, one water powered and the other equipped with a steam boiler, cut timbers and boards. At least 11 soldiers and civilians brought their wives; there were nearly a dozen children as well. Carrington’s household included his wife, two sons, and an African American butler.

The fort’s artillery consisted of a 12-pounder field howitzer and three mountain howitzers. Designed to fire standard 12-pounder ammunition, the mountain howitzer had a brass barrel only 39 inches long. The little guns could be dismantled and carried on a pair of mules, with another mule carrying ammunition and gunner’s implements.

Carrington sited the fort inside the “V” formed by the junction of Big Piney and Little Piney Creeks. Between the streams rose a ridge, which Carrington called the Sullivant Hills, after his wife’s family. To the north, the Sullivant Hills descended into the valley of Big Piney Creek. Beyond the Big Piney to the north rose the heights of Lodge Trail Ridge. The Bozeman Trail ran close to the northern wall of the fort. It skirted around the eastern edges of Lodge Trail Ridge, and then ran north and west toward the valley of Peno Creek. The fort stood on a commanding position with little cover offered to potential attackers. Carrington established a signal station on a rise called Pilot Hill just south of Little Piney Creek.

During the journey from Fort Phil Kearny, Carrington had met Brule Sioux chief Standing Elk. Although his people sought peace, there were Miniconjou and Oglala bands in the Powder River country that had not consented to the treaty agreements signed at Fort Laramie, Standing Elk told Carrington. He also informed Carrington that the Cheyenne and Arapaho supported the hostile Sioux.

Among the leaders seeking to eject the soldiers from their lands was 44-year-old Oglala Sioux Chief Red Cloud. Red Cloud’s band had moved in the 1830s into the North Platte River valley near the new trading post of Fort Laramie. Red Cloud gained fighting experience and an increasing degree of respect as he took part in raids and battles against Crows, Pawnees, Utes, and Shoshones. He became a chief through his proven leadership in numerous clashes, rather than from a hereditary claim.

To Red Cloud and his allies, the arrival of hundreds of soldiers working on new forts indicated that the whites meant to seize these lands. Although the land technically belonged to the Crow Indians, the Sioux had taken control of them given that they were rich in buffalo.

Red Cloud was determined not to let the summer pass without taking action. Cheyenne Chief Two Moons stated years later that he and some companions visited Fort Phil Kearny during the summer of 1866. As they scanned the fort’s defenses, they talked with the legendary mountain man and army scout Jim Bridger, who was an old acquaintance. Bridger pointed out the fort’s four guns, and Two Moons was well aware of the deadly case shot they fired. The Cheyenne scouts believed that an attack on the fort, which was well protected by the guns, would be doomed to failure.

Even without firsthand intelligence from Two Moons, Red Cloud was unlikely to try launching a direct assault on a sturdy log stockade bolstered with artillery. It was much more practical to attack isolated messengers, supply trains, livestock tenders, and hunters outside the range of the fort’s guns.

The fort’s need for fresh timber was its weakness. The closest suitable woodland was about four miles west of the fort at Piney Island where there was a stand of pines 90 feet tall surrounded by tributaries of Piney Creek. On most days, at least a couple of dozen wagons with civilian teamsters rolled along a road south of the Sullivant Hills to Piney Island. Even heavily escorted trains faced ambushes, and the timber cutters worked in constant peril. Log blockhouses protected the two timber camps. Even when the soldiers were barricaded in the blockhouses, Indians could shoot them by firing through the loopholes.

A war party slipped close to the fort on July 17 and made off with some of the Army’s livestock. Two soldiers were killed and three wounded in the subsequent pursuit. Another soldier was killed a week later when several hundred warriors blocked a wagon train coming from Fort Reno. A relief party from Fort Phil Kearny, with a mountain howitzer, drove off the attackers.

The Indians attacked eight other wagon trains in the second half of July. Over the next few months, Carrington reported 51 skirmishes in which Red Cloud’s men probed the fort’s defenses. Between August and mid-December 1866, the Indians killed more than 70 soldiers and civilians around Fort Phil Kearny. Raiding parties rode off with approximately 700 government horses, mules, and cattle.

Lone hunters or travelers were in special peril. Ridgeway Glover, an artist-correspondent for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, disappeared after ignoring frequent warnings against leaving the post alone. His body was found, decapitated and scalped, on September 17. Glover had been taking photos of the fort and the area for the newspaper. No trace was found of his camera, nor of the only photographs ever taken at Fort Phil Kearny.

Red Cloud’s campaign attracted hundreds of new allies during the summer and fall of 1866. To the U.S. Army soldiers, Red Cloud was the commanding general of an enemy army. In reality, his authority was more complicated, holding some sway over a loose alliance of essentially independent Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho bands. By and large, his reputation as a successful war leader kept 2,000 warriors following the broad outlines of his strategy during the fighting in 1866.

Amid the growing harassment by Red Cloud’s mounted warriors, Carrington had no cavalry at Fort Phil Kearny. He had to improvise with mounted infantry, but few of the men were experienced riders. In any case, all three forts were short of serviceable horses.

Most of Carrington’s men carried single-shot, muzzle-loading Springfield rifled muskets, and some mounted soldiers lacked revolvers. A number of the Sioux and Cheyenne had obtained repeating rifles or revolvers from Indian traders or by capture.

Cooke notified Carrington on August 11 that two companies of the 2nd Cavalry were going to join him. Company C of the 2nd U.S. Cavalry, which was led by Lieutenant Horatio Bingham, was the only one that arrived. Company C did not arrive until November 3. “Be very cautious,” warned Cooke. “Don’t undertake unnecessary, risky detachments.”

Arriving with Bingham was Captain William J. Fetterman of the 18th Infantry. Fetterman’s background is obscure, but he was commissioned as a first lieutenant in the same regiment back in May 1861. In contrast with his colonel, Fetterman had an active combat career during the Civil War and was brevetted lieutenant colonel for his services during the Atlanta Campaign.

At least 10 of the other infantry officers who served at the fort also had received one or more brevet promotions for gallant and meritorious service during the Civil War. Some officers chafed under the colonel’s orders that allowed only measured reactions. “I can take 80 men and go to Tongue River,” Fetterman told Carrington. The old scout Jim Bridger heard the young officer’s brash statement. “Your men who fought down South are crazy!” Bridger said in astonishment. “They don’t know anything about fighting Indians.”

Bridger had heard ominous news from some Crow warriors, whose people were yet at peace with both sides in the simmering conflict. They told Bridger it took half a day for them to ride through the camps of Red Cloud and his allies. Red Cloud tried to persuade the Crow to join him. He told the Crow that he intended by wintertime to starve the soldiers out of their forts and kill them.

Red Cloud carried out a sharp attack on a wood train two miles from the fort on December 6, 1866. Carrington sent Fetterman 35 cavalrymen and some mounted infantry to drive away the Indians and pursue them along their expected route of withdrawal through the Sullivant Hills. Meanwhile, Carrington intended to close in behind the Indians with 25 mounted infantrymen. It was the first time the colonel had ridden into action.

Carrington’s plans failed when the band of 100 warriors, who seemed to be fleeing, suddenly turned around and attacked. They surrounded Carrington’s party for several anxious minutes. Under heavy pressure, the Plains Indians routed the soldiers. They killed two men and mortally wounded another. As a result, Carrington became more cautious than ever. His garrison at Fort Phil Kearny numbered only 350 men. What is more, their supply of ammunition was down to about 45 rounds per man by mid-December.

The Plains tribes were greatly pleased with their performance in the December 6 action. Based on their success, the tribes agreed to combine for a new attempt to lure a larger party of soldiers away from the fort, and then surround and annihilate them.

Several dozen of Red Cloud’s riders again attacked a wood train on December 19. As Carrington feared, the raiders intended to lure a relief force into range of several hundred warriors hidden nearby. Captain James Powell led the fort’s response that day. Powell, who enlisted back in 1848, had years of experience in the antebellum dragoons and cavalry on the frontier. The old frontier hand drove off the attackers but did not follow them.

With the attacks on his isolated garrison growing more dangerous, Carrington decided to halt the wood-cutting expeditions. The wood train ordered to go out on December 21 was to be the last until the spring of 1867.

On the night before the final wood train, Captain Frederick H. Brown was awaiting transfer to Fort Laramie. “The night before the [massacre] he made a call with spurs fastened in the buttonholes of his coat, leggings wrapped, and two revolvers accessible,” recalled Margaret Carrington, the captain’s first wife. Brown said that he was ready for action “by day and night and must have one scalp before leaving,” she wrote.

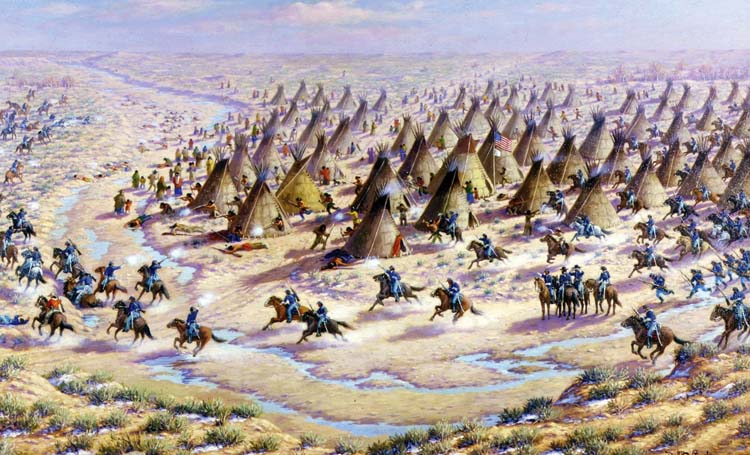

December 21 also was the date Red Cloud had chosen for his most ambitious operation yet. His plan called for an initial attack on the wood train to be followed up with an ambush of the relief party that he expected to be sent from the fort. To lure the relief party into the ambush, Red Cloud’s raiders would ride past the Sullivant Hills and Lodge Trail Ridge. Across the ridge, the ground sloped down to a narrow plain around Peno Creek and its small tributary streams. Hundreds of warriors would lie hidden in the grasses and brush of the bottom lands waiting to fall upon their pursuers.

The wood train, with 30 soldiers and 65 armed civilian teamsters escorting 35 wagons departed at 10 am on December 21. They rolled under bright blue skies on a bitingly cold day. One hour after the wagons passed through the fort’s gate, signals from Pilot Hill warned that the train was under attack.

Inside Fort Phil Kearny, Captain Powell prepared to lead a relief force to the wagons. Citing seniority, though, Fetterman went to Carrington and demanded command of the expedition. Fetterman had attained his captaincy in 1861, nearly three years before Powell reached that rank.

Carrington acquiesced to Fetterman’s demand. He placed Fetterman in command of three officers and 77 men. With them went civilian volunteers James Wheatley and Isaac Fisher. As civilian employees of the quartermaster department, both volunteers were armed with Henry repeating rifles. These breech-loading, lever-action rifles held 16 metallic cartridges.

The soldiers numbered 49 men from the 18th Infantry and 27 from the 2nd Cavalry. Lieutenant George W. Grummond and Captain Brown joined Fetterman. It would be Brown’s last chance to fight the Indians before he departed for Fort Laramie. Although an infantry officer, Grummond was placed in charge of the horsemen, as Bingham’s death left no cavalry officers at the fort.

Carrington stated afterward that his orders to Fetterman were as follows: “Support the wood train, relieve it, and report to me. Do not engage or pursue Indians at its expense; under no circumstances pursue over the Ridge, namely, Lodge Trail Ridge, as per map in your possession.” Grummond’s orders were to obey Fetterman’s commands and to stay with him. Some witnesses later confirmed hearing the orders, but others did not.

Fetterman left the fort about 11:15 am, leading the 49 infantrymen. Serviceable mounts were too few to accommodate that many soldiers, so they marched out on foot. Captain Brown could ride with them only because he had borrowed Calico, a pony belonging to Colonel Carrington’s son Jimmy. Grummond led the horsemen out a few minutes later.

As no medical officers accompanied the wood train or Fetterman’s patrol, Carrington summoned C.M. Hines, an assistant surgeon under contract to the U.S. Army. The colonel ordered Hines to accompany the wagon train and to treat any casualties he found. Moreover, he was to catch up with Fetterman if possible. Shortly after Hines departed, the Pilot Hill station signaled that the attack on the wood train was over, and the wagons had resumed their trip to the timbering site.

Although Red Cloud was not present, the looming battle was the result of his successful months-long campaign against the three Bozeman Trail forts. Fetterman’s orders were to march south of the Sullivant Hills to the wood train. With the wood train no longer under attack, Fetterman focused on the handful of mounted warriors who taunted the soldiers. Among the decoys were a number of highly respected warriors of the Northern Plains tribes, such as Morning Star, Crazy Horse, Black Shield, Big Nose, and White Bull. Some of the chiefs had extensive experience. For example, Cheyenne Chief Morning Star (known as Dull Knife to the U.S. Army soldiers) was a veteran of four decades of raiding and warfare. These great warriors would become famous in the final years of the Sioux Wars.

Believing that he outnumbered his enemies, Fetterman followed them past the eastern slopes of the hills. The warriors plodded slowly along toward Lodge Trail Ridge, rather than galloping away from the slow-moving foot soldiers. Crazy Horse even dismounted and performed an elaborate pantomime of a man tending to his bridle. Crazy Horse and his riders slowly disappeared beyond the ridge.

Fetterman marched to the Bozeman Trail itself and turned left to follow the road west along icy Peno Creek. In a short time, Fetterman could no longer be seen by lookouts from the fort. None of his men was ever seen alive again by their fellow soldiers. What unfolded next can be pieced together only from evidence found on the battlefield, stories related years later during interviews with Indian participants, and archaeological finds made many decades afterward.

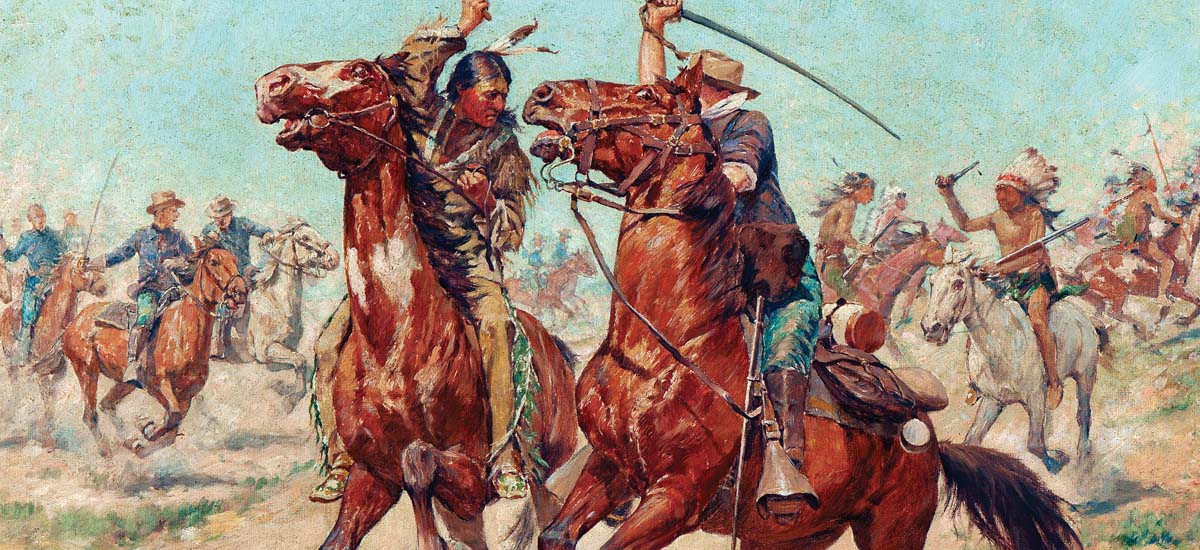

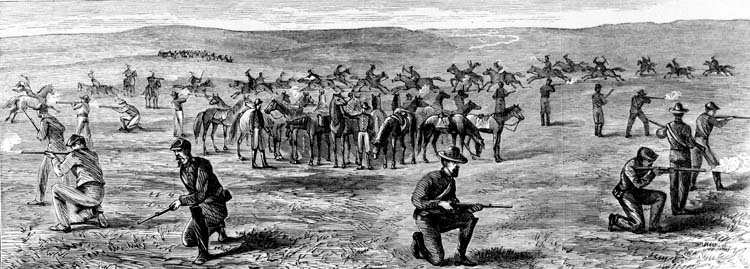

Grummond and the cavalry, with Wheatley and Fisher, rode ahead of the infantry. They opened fire, bringing down a few Indian riders. The decoys crossed the frozen ford of Peno Creek. They formed two groups and rode away from each other, but then turned and crossed their paths. Nearly 2,000 hidden Sioux and Cheyenne recognized this as the prearranged signal to unleash their ambush. Scores of warriors rose up from concealed positions in the grass and brush and let loose a barrage of arrows. They were soon joined by hundreds of other warriors.

A few Indians, emboldened enough to ride headlong among the solders, were shot dead. Wheatley and Fisher dismounted, and a few cavalrymen joined them. The two civilians, who took cover behind some large rocks and a few dead ponies, cut down warriors and their mounts with their Henry repeating rifles.

The rest of the cavalrymen made for a nearby ridge topped with rocks and boulders. Grummond never made it to the ridge. With the hilt of his saber tightly gripped in his hand, Grummond was shot and killed in the roadway of the Bozeman Trail.

A short distance behind the cavalry, Fetterman led the infantry back toward high ground, where they sought cover amid a collection of boulders on the rocky slope. Captain Brown dismounted and, after sending away his borrowed pony, joined Fetterman. Among the rocks, Fetterman’s men reloaded and fired again, their volume of fire growing weaker as the Indians picked them off one by one.

For a few minutes, Wheatley and Fisher fended off their attackers with the Henry repeaters. Soldiers inspecting the battlefield later counted 60 splashes of blood scattered on the frozen ground, giving mute testimony of the effectiveness of the Henry rifles. When their ammunition ran out, they were quickly overwhelmed and slain.

So many Sioux and Cheyenne surrounded Fetterman that many arrows missed soldiers, and flew on to hit Indians on the other side of the dwindling band. Within 20 minutes, the Indians had slain the last of the soldiers. It was obvious that desperate hand-to-hand fighting had occurred given that some of the men were obviously slain by war clubs and lances in the final moments of their doomed stand.

Carrington reported that Brown and Fetterman shot each other rather than fall prisoner. It seems possible, however, that Brown shot himself. But a post surgeon named Samuel M. Horton found that Fetterman died of violent slash wounds to his chest and throat. This matches the account of Oglala leader American Horse, who told of knocking Fetterman down and killing him with a knife.

Atop their ridge, the last of Grummond’s cavalrymen struggled across the icy surface until they found good cover amid a cluster of boulders. To the south, they saw a virtual sea of enemies. There was no chance of anyone getting back to the fort. Their horses driven away, the troopers fired into the mass of warriors pressing in on them. It was only a few minutes until the last soldier was cut down.

A barking dog that had belonged to one of the dead soldiers broke the silence. “All are dead but the dog,” said one of the victors. “Let him carry the news to the fort.” But another warrior was against letting the dog get away, so he killed it with an arrow.

Back at Fort Phil Kearny, it was just before noon when the garrison heard gunfire. “A few shots were followed by constant shots, not to be counted,” wrote Carrington. Hines soon returned with chilling news. He had been able to ride only as far as a hill some distance from the fort. He hurried back when he saw only a vast array of Sioux and Cheyenne and no trace of Fetterman’s men.

Carrington ordered 75 men under Captain Tenedor Ten Eyck to relieve the embattled detachment. Moments after Ten Eyck left the fort, the colonel dispatched 40 more men to join them. Most of Ten Eyck’s men marched on foot. When they reached the Big Piney, they had to remove their shoes and stockings to ford the ice-covered stream.

Carrington then sent an ambulance and two wagons with a few crates of ammunition to follow Ten Eyck. Forty armed teamsters accompanied them. A quick count found only 119 men left in the fort, including civilian employees and some prisoners who were released from the jail.

About three miles from the fort, Ten Eyck halted on high ground to the right of the road rather than pressing on to rescue Fetterman. This prudent step later brought denunciations and accusations of cowardice down on Ten Eyck. Neither boldness nor caution would have made the slightest difference. All of Fetterman’s 80 men were already dead before Ten Eyck’s men stepped out of the fort.

From the heights, Ten Eyck’s troopers could see only the vast Indian forces, celebrating their victory. Neither the victors nor the small army detachment moved to attack, and the Sioux and Cheyenne drifted away to the west. There would be no more fighting that day.

Moving down into the valley, Ten Eyck’s men walked into the grim horror of the silent battlefield. Following age-old custom, the victorious warriors had slashed and mutilated the dead. Everywhere the soldiers turned in the freezing wintry air they saw corpses, severed body parts, and pools of blood.

Civilian teamster Finn Burnett, one of the men who retrieved the slain soldiers, noted one exception to the violent mutilations of the dead. The body of Bugler Adolph Metzger was left untouched after his death. Near the German-born soldier’s lifeless body was his bugle. Crumpled and battered, the bugle had served Metzger as a war club in his last moments. Burnett said he found Metzger’s corpse covered with a Sioux buffalo robe, left behind as a mark of respect for his courage.

Eighty-one men from the fort and a handful of their mounts, including Jimmy Carrington’s pony Calico, lay dead. Among the slaughtered corpses of the soldiers and their dead horses was only one survivor, a cavalry mount named Dapple Dave. A dozen arrows had plunged deeply into the dying horse. The final shot of the day echoed over the bleak landscape when Ten Eyck ordered a soldier to shoot the suffering animal.

Only half a dozen soldiers bore evidence of gunshot wounds. Nearly all of the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho in the battle were armed with traditional weapons, such as bows, lances, and clubs. By one estimate, nearly 40,000 arrows were loosed in the approximately 40-minute-long battle. Red Cloud’s exact losses are unknown; however, interviews with the participants in later years indicate about 60 dead and 300 wounded.

Ten Eyck’s three wagons were able to bear only about half the dead; the rest of the slain remained frozen where they fell until they could be retrieved the next day. When the macabre procession reached Fort Phil Kearny, the state of the dead shocked and horrified everyone. The wagon loads of bodies reminded Hines of “hogs brought to market.” Young Jimmy Carrington would have nightmares for many years afterward when his dreams took him back to that grim evening.

Oddly enough, the wood cutters had reached Piney Island in peace, out of hearing range of the desperate battle on Lodge Trail Ridge. They returned safely to the fort and added their numbers to the garrison. Bracing for a potential all-out assault that might overwhelm the fort, soldiers formed wagon boxes into three concentric rings surrounding the magazine. All of the women and children were ordered to stay by the magazine. If the fort was overrun, Carrington himself would touch off the Army’s gunpowder to prevent the families from being taken prisoner.

Carrington dashed off messages and distributed them to several couriers in the hope that at least one would get through. Philips, a native of the Portuguese-owned Azores, rode 236 miles to the nearest telegraph station. Pushing on to Fort Laramie, he interrupted the post’s Christmas ball with news of the destruction of Fetterman’s command. Philips’ harsh four-day trek through sub-zero temperatures and as much as five feet of snow became a legend on the plains. It took 16 days for reinforcements from Fort Laramie to push their way through the deep snow and ice to Fort Phil Kearny; nevertheless, help did arrive before any attacks were made on the fort.

The slaughter of Fetterman’s force was the army’s worst disaster in the Indian Wars since Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair’s army was mauled by the tribes of the Western Confederacy at the Battle of the Wabash on November 4, 1791. It was easy enough for the War Department and the general public to decide that the Bozeman Trail was not worth its cost in blood. At any rate, the new Union Pacific Railroad would soon swiftly carry thousands of passengers closer to the gold fields. A new agreement, the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, gave the Sioux a large reservation that included the Black Hills of South Dakota. In keeping with this agreement, the U.S. Army abandoned its Bozeman Trail forts and closed the route to white travelers.

On July 31, 1868, the U.S. government withdrew the last troops from the treaty lands. The 120 men were buried in the post graveyard of Fort Phil Kearny. Carrington’s carefully built fort on the Little Piney was destroyed by fire. Whether the fire was set by a departing soldier or by one of the victors of Red Cloud’s war is unknown.

Peace lasted only until a gold strike in the Black Hills in 1874 brought another wave of miners and settlers through the Powder River country. This wave was even greater than the previous one. But the immediate aftermath of the Fetterman Fight and the subsequent negotiations meant that Red Cloud’s war was a rare victory for the Plains Indians in the long struggle to protect their lands and way of life from white encroachment.

Was Fetterman an arrogant and reckless officer, or simply a confident commander who ended up in the wrong place at the wrong time? He had been popular with his men, who found him brave, competent, and considerate of their well-being. The U.S. Army honored him by naming a new post, Fort Fetterman, after him in 1867. Conflicting views of Fetterman appeared after press reports in the East sought to assign blame. In the wake of the reports, political infighting engulfed the U.S. Army high command.

Cooke removed Carrington from his post few days after the battle. Carrington faced trouble from some of his former subordinates who admired Fetterman much more than they did him. His superiors proved to be even more serious adversaries. It was plain that Fort Phil Kearny was undermanned and that the Army was grossly negligent in failing to provide the endangered outpost with enough horses, modern weapons, and sufficient ammunition. As a result, Cooke and some other high-ranking officers tried to deflect blame by citing Carrington as incompetent.

Carrington in his defense painted Fetterman as an irresponsible hothead whose rash decisions doomed his men. Carrington would state time and again that he had forbidden Fetterman to cross Lodge Trail Ridge, and that the captain’s direct disobedience of orders was the cause of the catastrophe. Carrington was officially exonerated. Yet his report was suppressed for years, and he never held active command again before his retirement in 1870.

Carrington was married to two writers whose work permanently tinted the perception of the Fetterman fight. His first wife Margaret wrote of the family’s life on the frontier in the 1868 book, Absaraka, Home of the Crows. After Margaret’s death in 1870, Carrington married Frances Grummond, the widow of Lieutenant Grummond who died in the ambush. Frances Carrington’s 1910 book, Army Life on the Plains, also included the story of the 1866 battle. Both women relayed the impressions of their husband, and they helped shape the enduring image of Fetterman as irresponsible and disobedient.

Lurid accounts in the Victorian press led to the battle being labeled as “the Fetterman Massacre” and the “Fort Phil Kearny Massacre” for many years. The Sioux called it the Battle of the Hundred Slain, from a prophecy that before the clash foretold the death of 100 soldiers. The fateful clash that had unfolded on December 21, 1866, had the distinction of being the worst disaster to befall the U.S. Army during the Indian Wars since 1791. It was eclipsed a decade later by Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer’s defeat at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in June 1876.