By Christopher Miskimon

It was dark and difficult to see on the night of April 18, 1966, but the U.S. Navy was counting on that. The aircraft carrier USS Kitty Hawk prepared three aircraft for launch from its powerful catapults. A Soviet intelligence-gathering ship was nearby, so the planes operated under radio silence. A pair of A-6 Intruder attack planes quickly rose from the carrier’s deck accompanied by an E-2A Electronic Warfare aircraft for later communications. Commander Ron Hays, executive officer of Squadron VA-85, piloted the lead plane with his bombardier-navigator Lieutenant Ted Been seated next to him. Lt. Cmdr. Bill Yarbrough and bombardier-navigator Lieutenant Bud Roemish flew the other A-6 as their wingmen.

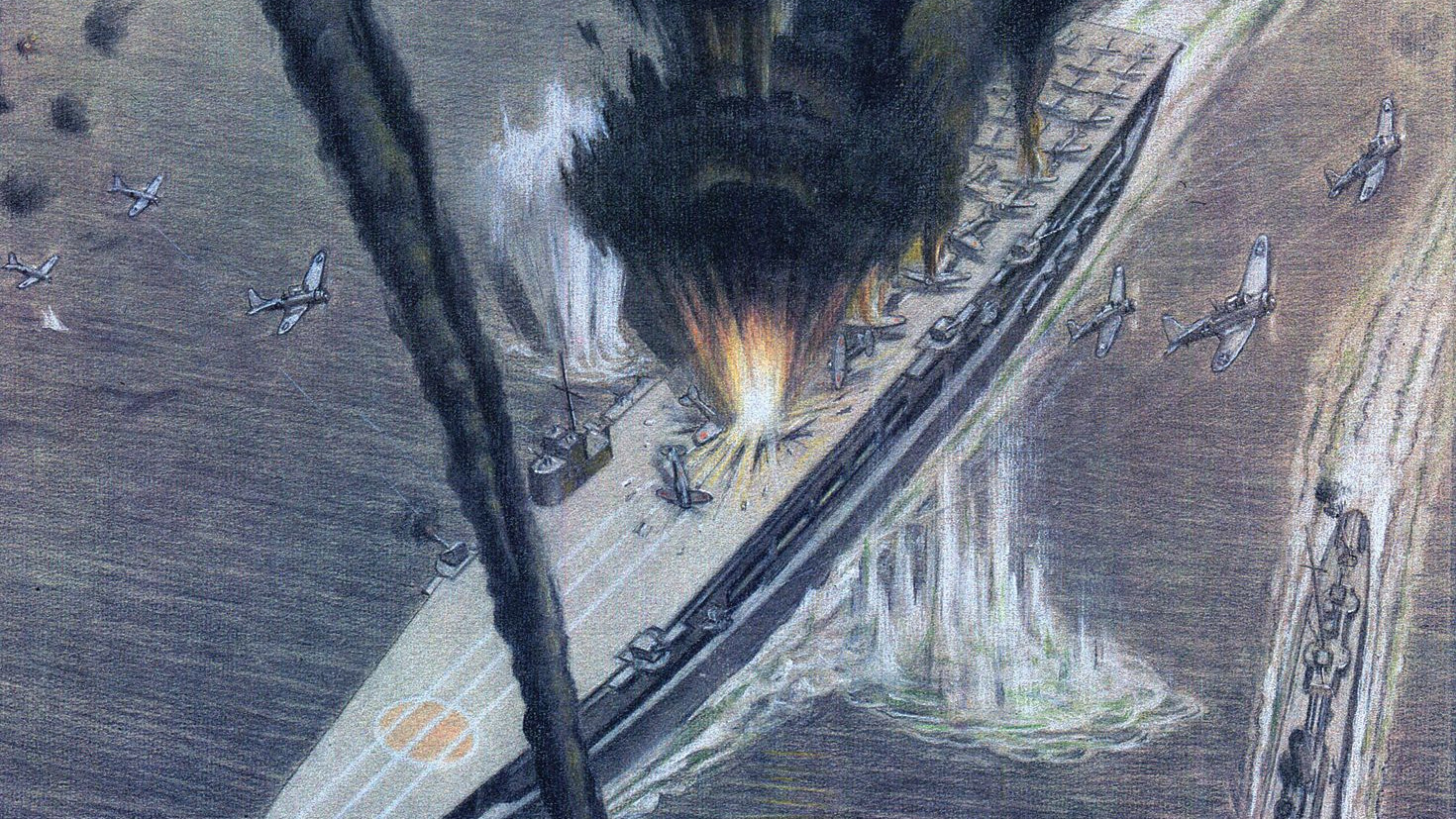

Their target was the Uong Bi powerplant, 12 miles north of Haiphong, a port city in Communist-controlled North Vietnam. The Intruder’s crews rendezvoused soon after takeoff and leveled off below 500 feet, staying low to avoid enemy radar detection. They stayed that way until about 25 miles from the target and then began a slow climb to 1,800 feet, where they could safely release their bomb loads. Each A-6 carried 13 Mk. 83 1,000-pound bombs. Soon the powerplant, sitting on the northeast side of Uong Bi, appeared below. The pilots separated their aircraft laterally before Hays made his run, releasing all his bombs onto the target. The second plane had problems with its release mechanism but the bombardier-navigator was able to manually drop his entire load as well.

The North Vietnamese were taken by surprise that night. By the time they began firing their antiaircraft guns both Intruders were already on the way home. A later damage assessment counted at least 25 bomb craters in the target area with heavy damage to the plant. The next day the North Vietnamese released a press statement in which they attributed the destruction to the B-52 Stratofortress. This was because the North Vietnamese were not yet fully aware of the payload and night attack capabilities of the newly introduced A-6 Intruder, but in the coming years they would learn this lesson, much to their detriment.

The A-6 Intruder had only been in service a few years when it was deployed to Vietnam. The design arose from a Navy requirement for a medium attack aircraft capable of flying in all weather and carrying out night operations. Before this the Navy’s ability to carry out attacks at night was severely limited by the available aircraft and technology. Targeting systems were primitive and many pilots operated more by moonlight or flares to find their targets. Skyraiders and A-4 Skyhawks carried out the light attack function while the larger A-3 Skywarrior filled the heavy attack role, including using nuclear weapons. The medium attack function really came to embody the concepts of all-weather and nighttime operations. Most jets of this era carried no more than 2,000 pounds of ordnance, and the new plane had to carry more.

The requirement was sent to 13 aircraft companies. Grumman’s A2F-1 won the competition from a field of eight submissions. In an era where jet aircraft were usually sleek with pointed noses and slim fuselages, the Grumman design had a large, blunt nose and a thick middle that tapered to the rear. Although it was dubbed the “Flying Drumstick,” Grumman officials asserted that they were focused on engineering performance and not on aesthetics. The plane was to be a bomber, and it was engineered to fulfill that specific role.

The thick nose held new ground-mapping and targeting radars necessary to bomb accurately in the dark and under the adverse conditions envisioned for the plane. The cockpit layout seated the pilot and bombardier-navigator next to each other, increasing the fuselage width but allowing them to work together more effectively. The A2F-1 carried the Litton Company’s ASQ-651 digital integrated attack navigation equipment, which enabled the crew to fly at night over rough terrain at low altitudes. It could do this in most weather conditions. “All-weather” is something of a misnomer as some weather is too severe for any flying. It was a complicated system that gave occasional trouble but was still a leap ahead in flying technology. The Navy also noted the Air Force had nothing similar in service. The system proved accurate enough that other attack aircraft often flew alongside the A-6 and dropped their ordnance at the same time.

The A2F-1 was standardized as the A-6A in late 1962 and entered active service in February 1963. The A-6A had a wingspan of 53 feet and could carry up to 18,000 pounds of ordnance on five external hardpoints. Typical loads consisted of 500-, 1,000-, or 2,000-pound bombs. While it had a combat radius of 900 miles, the Intruder was not a fast plane, with a maximum speed of only 685 mph compared to the supersonic aircraft of the day. The plane was not intended for speedy maneuvering, though. Its job was to put bombs on a target.

As the Intruder entered service it replaced the aging Skyraiders, with 10 squadrons converting to the A-6. Another pair of original A-6 squadrons were also formed. Ten of the 12 saw action in Vietnam. The Marine Corps also adopted the new plane and equipped six squadrons, with four of them serving in Southeast Asia. Marine Corps air crews flew the A-6 from both Da Nang and Chu Lai, as well as from carriers.

The A-6 suffered a high initial loss rate in Vietnam due to a mixture of mechanical failure, pilot inexperience, and enemy action. It is worth noting that accidental aircraft losses during the early years of carrier jet operations were higher than in the 21st century. A few days after the attack on the Uong Bi powerplant, a number of planes and aircrew were lost, with several men falling into North Vietnamese hands as prisoners, but there were also instances of success and heroism.

An A-6 from Squadron VA-85 was attacking barges north of the city of Vinh on April 27, 1966, when it was hit by enemy fire. A bullet struck the pilot, Lieutenant Bill Westerman, causing severe wounds. Bombardier-navigator Lieutenant Brian Westin reached across the cockpit to take the controls. There was no way to land safely so he pointed the plane out to sea. Bailing out over land meant probable capture by the North Vietnamese, but if they could get farther out to sea, it was more likely the Navy would find them first. Westerman was drifting in and out of consciousness, so after jettisoning the canopy Westin had to reach over and pull his friend’s ejection handle before pulling his own.

A helicopter soon arrived and pulled Westin from the water. The bombardier-navigator directed the rescuers back down the Intruder’s track until they found Westerman afloat. There was no diver on the helicopter to help the stricken pilot into the rescue sling, so Westin dove back into the water and hooked Westerman into the sling before waving the helicopter off to get the wounded pilot to treatment. Another helicopter arrived five minutes later to again rescue the bombardier. Brian Westin would be the first of 14 Intruder crewmen to be awarded the Navy Cross for heroism.

Despite the loss rate, the A-6 acquired a reputation for single-plane night attacks flown at very low altitudes. In most instances, the Intruder could penetrate heavily defended enemy airspace, drop its payload with precision, and exit the area before an effective response could be mounted. Even when the North Vietnamese did detect the plane and fire at it, the increasingly skilled aircrews could often get through and get away again.

One example is an attack carried out by Lt. Cmdr. Charlie Hunter and his bombardier-navigator Lieutenant Lyle Bull on October 30, 1967. They took off from the USS Constellation and flew through the darkness toward Hanoi. Their target was the Red River ferry docks and their A-6A carried 13 Mk. 83 1,000-pound Snakeye cluster bombs. A single plane night attack was risky. Bull recalled the area was protected by 20 SA-2 surface-to-air missile sites and 600 antiaircraft guns. An earlier attempt to destroy the docks using a large number of planes failed due to the heavy defenses.

The Intruder reached the coast north of Vinh and headed northwest toward Hanoi with Hunter using the terrain to mask their approach. Bull was using the radar, marking their path using its returns. At about 20 miles from the target the plane left the covering terrain features and was immediately targeted by antiaircraft guns followed by missiles, even though they were flying below 500 feet. “Intelligence reported the SA-2 couldn’t track below 1500 feet,” recalled Bull. “We were disturbed to see that their assessment was incorrect.” Hunter carried out a high-speed barrel roll that threw the missiles off target and took the A-6 as low as 50 feet.

Gunfire continued to flash at the A-6 as it reached the docks. Despite the incoming fire, Bull managed to drop his bombs on target and then Hunter flew them out of the engagement area. The Intruder made it safely back to the USS Constellation. Hunter and Bull received the Navy Cross for their actions. Both men stayed in the service and rose to the rank of rear admiral.

Once commanders and planners realized the Intruder’s strengths, the squadrons flying them began to get commensurate assignments. The night attack capability came as an unpleasant surprise to North Vietnamese troops moving along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a logistics line used to move supplies and soldiers into South Vietnam through Laos and Cambodia. The Intruder’s targeting system also included a device called the moving target indicator, which helped target these moving troops at night. The North Vietnamese generally did not move during the day to avoid be spotted and targeted, but they were very comfortable travelling at night.

Entire convoys were bombed with practically no advance warning. The Intruders would often drop cluster bombs first, which punctured fuel tanks and set off ammunition, starting fires the pilots could use for followup attacks. Often the North Vietnamese would fire tracers into the air despite the low chance of a hit, just to warn the convoys in the area that American aircraft were overhead.

The Navy and Marine Corps refined strike tactics to improve the crew’s chances. If an attack involved multiple planes, flying in a column, one after the other, it allowed antiaircraft gunners to better target the following aircraft. Instead, the A-6s flew in from different headings a few seconds apart. To reduce the chance of mid-air collisions, the planes would come in at different altitudes, timed to be a few seconds apart. This minimized the opportunity for gunners to shoot at them, and some aviation experts even compared the tactic to the precision flying done by the Navy’s demonstration unit, the Blue Angels.

The side-by-side crew configuration proved to be a great benefit to the aircrews. Marine Corps pilot Bruce Byrum flew more than 3,000 hours as an A-6 pilot and praised the role his bombardier-navigator played. He monitored the radio and watched airspeed, power settings, attitude, and rate of descent. The bombardier-navigator also oversaw the plane’s place in the landing pattern as Intruders returned to their carrier. “He had as much to do with the pilot’s success as the pilot,” Byrum recalled.

This relationship created a great sense of teamwork and camaraderie. “With two guys sitting side by side, you could communicate with hand gestures, if need be,” said Commander Robert “Rupe” Owens. “You could simply look at the other guy and nod.”

On February 26, 1967, Intruders of VA-35 flew from the deck of the nuclear-powered carrier USS Enterprise to drop aerial mines in two rivers. They were the first unit to drop such mines since World War II. VA-35 lost one A-6 in its tour during a strike against Hanoi during Ho Chi Minh’s birthday on May 19, 1967. An A-6 flown by Lt. Cmdr. Gene McDaniel and bombardier-navigator Lieutenant Kelly Patterson was hit by a missile during the attack. Both men ejected. Patterson died in captivity while McDaniel spent six years in prison. He was later awarded the Navy Cross for his leadership while a prisoner.

One of the blackest days for the A-6 came a few months later. On August 21, 1967, four A-6As of VA-196 launched from USS Constellation for a day attack against the Duc Noi railroad yard north of Hanoi. The weather was bad, with thunderstorms and heavy cloud cover over most of the country. On the way in, one plane was hit by flak, but the crew felt they could press on. As the Intruders moved in for the attack, another strike by U.S. Air Force planes was in progress nearby and they were taking fire as well, losing a pair of F-105s. The resulting large amount of emergency radio traffic made coordination even more difficult.

As the aircraft started their dives, a surface-to-air missile struck the Intruder flown by Commander Leo Profilet, a well-respected Korean War veteran. The plane burst into flames and Profilet ejected along with his bombardier-navigator Lieutenant Bill Hardman. Their fellow flyers saw their parachutes as they flew out of the target area. Both men survived but spent more than five years as prisoners of war.

The remaining three planes raced toward the coast but became separated in the bad weather. Only one plane returned to the USS Constellation; the other two were missing, but their fate was soon discovered. The Chinese government announced via radio it had shot down two U.S. Navy planes after they flew over their border. Bombardier-navigator Lieutenant Robert J. Flynn survived the ordeal. He was taken prisoner by the Chinese and held for more than five years, undergoing solitary confinement for most of that time. It was a dark day for the squadron and the Navy, losing three A-6s in one mission and even worse, seeing all the crews either killed or captured.

As the war progressed, new variants of the Intruder appeared. The A-6B was an initial attempt at a fire suppression aircraft specializing in attacking enemy radar and surface-to-air missile sites. A few A-6Bs would accompany A-6 squadron to assist in this role. The B model would eventually be replaced by the EA-6B Prowler, a specialized suppression aircraft that entered service toward the end of the Vietnam War and flew until March 2019.

The A-6C was fitted with a special pod carrying low-light and infrared cameras to further improve its ability to strike targets at night. A tanker variant, the KA-6D, also joined the Intruder squadrons to provide carriers with an improved air-to-air refueling capability. The A-6E was an improved attack version with better radar and navigation systems. The E model would serve the Navy until 1997, a victim of post-Cold War defense reductions.

The rugged A-6 also acquired a reputation for toughness despite the heavy losses Intruder squadrons sometimes suffered. Byrum recalled a daylight mission where one of his squadron’s planes took a hit that left a barrel-sized hole in the right wing. Although the pilot could not see it, the bombardier-navigator could. Since they were still over enemy territory, the bombardier-navigator chose not to tell the pilot about the damage, hoping to at least get to a friendly air base. Because the A-6 was not leaking fuel or hydraulic fluid, Byrum also decided not to inform the pilot.

The damaged A-6 made it safely to Da Nang and Byrum landed after it. By the time Byrum taxied over, the pilot of the damaged plane had shut down his engines and gotten out to inspect the damage. As Byrum watched, the shocked pilot knocked his bombardier-navigator to the ground, unhappy the man had not told him the truth. Byrum chose discretion and kept his cockpit shut so the enraged flyer would not try to do the same to him. “I don’t know what he would have done differently,” said Byrum. “He surely did not want to eject.”

Of the Intruders lost in combat in Southeast Asia, two were lost to MiGs, 10 to surface-to-air missiles and 36 to antiaircraft guns with more lost to accidents and mechanical failures. This was a small number of losses considering the Navy and Marine Corps flew 35,000 A-6 combat sorties over hostile territory that bristled with the most extensive air defense network in the world at the time. Worse than the loss of aircraft was the loss in lives. The Navy and Marine Corps lost 92 A-6 aviators and 53 other A-6 aviators became prisoners of war.

Rear Admiral James Seely placed great value on the Intruder’s contribution. “In my opinion the A-6 was the most effective strike aircraft the U.S. Navy had during the Vietnam War,” said Seely. “It could do day missions as well as any other aircraft, and was much superior at night. We had system problems with the A-6A, but it was in fact the only true all-weather aircraft in the fight.”

Some of the most demanding missions of the war were assigned to Intruder crews and they carried them out with courage and determination. Many A-6 crewmen would go on to command positions after the war, seeing the aircraft’s service through the remainder of the Cold War.