By Eric Niderost

On the evening of May 30, 1857, Julia Selina Inglis was preparing to go to bed when she heard an urgent knocking on her door. The pounding alarmed her and she answered immediately. It was Martin Gubbins, an official with the Honorable East India Company. Gubbins was a no-nonsense individual who was not used to mincing words. “Bring your children and come up to the top of the house immediately,” he ordered.

Inglis and several other women were staying with Gubbins because his house was within the grounds of the Residency, the official British headquarters in the city of Lucknow in northern India. Because the Residency had been transformed into a garrison post, complete with armed troops, it was considered to be a place of refuge and safety.

Thousands of Indian soldiers, including sepoy foot soldiers and sowar cavalrymen, were in full mutiny against their British overlords, and the rebellious spirit was like an infection that was almost impossible to contain. The British tried to contain this growing rebellion, but efforts to nip it in the bud proved ineffectual and even ham fisted.

Lucknow, the capital of Oudh (modern-day Awadh) Province, nursed its own grievances, and it was only a matter of time before it joined the spreading mutiny. Heeding Gubbins’ command, Inglis quickly dressed herself and her children and went to the roof as fast as she could. After the rising tensions of past weeks, she had an inkling of what to expect, but was still shocked by the view.

It was 11 pm, but the inky void and its canopy of stars could not erase the terrible spectacle that presented itself. The European cantonments were on fire, with tendrils of yellow and orange flames leaping high into the air. Rebel sepoys were busy looting empty buildings before setting them to the torch. But there was fighting, too. Cannons boomed and the staccato popping of musket fire could be heard distinctly. Soon, a handful of Europeans and loyal Indians were under siege, an epic of endurance that would be long remembered even after British rule in India was only a memory.

The Great Mutiny had its roots in the political, cultural, and religious turmoil of the 1840s and 1850s. The East India Company grew more high handed and arbitrary, and its lust for wealth and territorial acquisitions more obvious and all consuming. The “doctrine of lapse” held that if there was no natural heir to a ruling family, the territory or state would be annexed by the British.

Sometimes, company dealings were even more direct and arbitrary. In the 1850s it cast covetous eyes on Oudh, a rich and prosperous state in northwestern India. Its ruler was Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, and he was deposed by the British in January 1856 on the grounds of having a corrupt administration. Many of the Nawab’s retainers and officials lost their positions, and some landowners lost their lands because they had no proof of ownership or their title was dubiously acquired.

The common people, mainly peasant farmers, were burdened with heavy taxes and feared loss of caste and religion with British rule. European missionaries meant well, but could scarcely conceal their contempt for the Hindu religion. Wild rumors circulated in northern India that the British and Europeans were dropping beef and pork pieces in drinking wells at night. Cattle are sacred animals in the Hindu religion, and pork is forbidden to people of the Muslim faith.

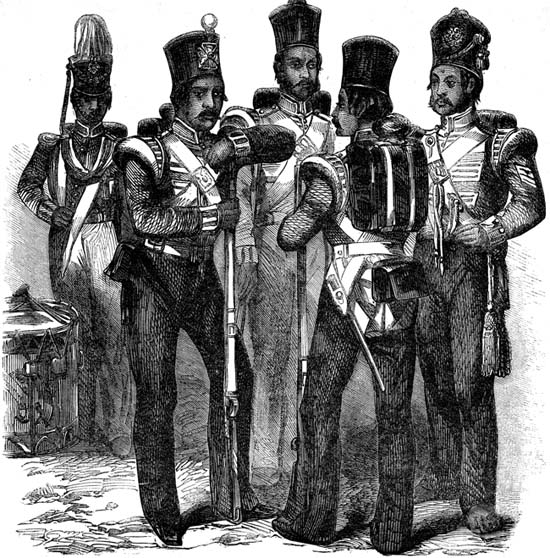

The company’s Bengal army had its own grievances. Many Bengal army sepoys were recruited from higher castes like the Brahmins, and they were very conscious of their privileges. Fearful of losing caste if they traveled overseas, Bengal sepoys initially were exempt from such deployments. The British grew impatient with such arrangements and started to introduce soldiers who were available for foreign service, men like Sikhs from the Punjab and Ghurkas from Nepal. Bengal soldiers resented this seeming loss of prestige.

Conservative Indians intensely disliked the changes the British were introducing into the subcontinent. The railroads and telegraph, seemingly works of the devil, were strange and alien in concept. The British also allowed widows to remarry, tried to suppress female infanticide, and abolished sati, the customary practice of a widow throwing herself on her husband’s funeral pyre. These reforms, and the suppression of sati, were deeply resented. Sati was not widely practiced, and other reforms may have had minimal impact on most Indians, but that was not the point. The point was foreign meddling with time-honored Indian customs that were centuries old.

Many Indians regard the Great Rebellion as India’s first war of independence. This is perhaps overstating the case; the deposed rulers and threatened upper classes had their own axe to grind, and common Indian farmers were oppressed and feared for their culture and religion. But it is true that the Great Mutiny planted the seeds of a true Indian nationalism that sprouted later in the century.

The Great Rebellion of 1857 also was called the “Devil’s Wind,” and it is an apt description. Partly though misplaced idealism, partly through arbitrary and high-handed politics, partly though cultural and racial arrogance, the British sowed the wind and would soon reap the whirlwind.

The Enfield rifle was introduced in India in the spring of 1857, but rumors spread that its cartridges were greased with the fat of cows and pigs. The cartridge controversy was the spark that soon had all of northern India ablaze.

It began at Meerut, where elements of the 3rd Bengal Light Cavalry refused to accept the cartridges when drilling. No fewer than 85 were court-martialed for their disobedience, and most were sentenced to hard labor. The next morning, which was a Sunday, the remainder of the 3rd Cavalry openly revolted and freed their imprisoned comrades. Other Indian units joined the growing rebellion, and soon no European was safe.

Rebel sepoys killed the British officers who tried to stop them, and before long European homes were attacked. Men, women, and children were killed without mercy, and the death toll included 50 Indian servants who tried to conceal or otherwise save their employers. The mutineers, triumphant and nearly ecstatic with joy, marched to Delhi 50 miles away.

Delhi had great symbolic significance, especially because it was the capital of the moribund Mogul empire. Delhi fell to the mutineers, a psychological blow to the British that simultaneously boosted rebel hopes and aspirations.

Brigadier General Sir Henry Lawrence had been chief commissioner of Oudh Province for only a few months when the storm broke. Level headed, experienced, and fair, he did his best to calm the troubled political waters and make things right, but he ran out of time. When he heard of the events that occurred at Meerut and Delhi he knew that Lucknow would be targeted by the insurgents sooner or later.

When Lawrence took a survey of the Lucknow area, he did not like what he saw. Troop locations were scattered, often miles apart. The main soldier cantonments were at Muriaon, three miles away from the Residency, and consisted of three regiments of native infantry, the 13th, 48th, and 71st, two batteries of native artillery, and one battery of European artillery.

At Mudkipur, about a mile and a half farther, the 7th Light Cavalry and two regiments of irregular cavalry, the 4th and the 7th, were south of the River Gumti. The loyalty of all these regiments was problematic, but Lawrence hoped that his recent attempts to make things better might calm an increasingly volatile situation.

Lawrence had only one full European regiment on hand, the 32nd Regiment of Foot. It had been in Lucknow for about a year, and its troops were acclimated to India’s temperature extremes. Lt. Col. John Inglis, a seasoned officer who had served with this regiment for many years, commanded the regiment.

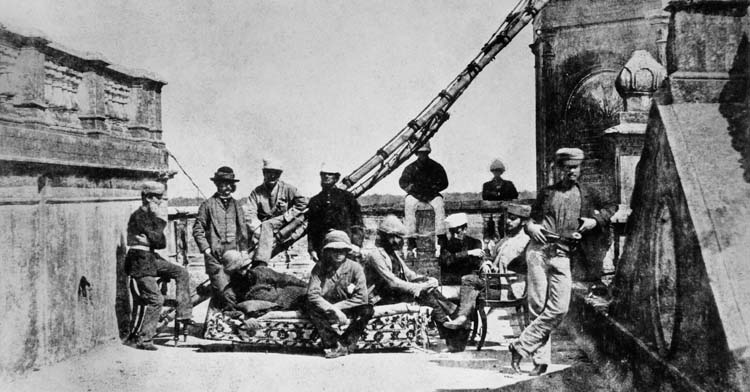

One of the commissioner’s first tasks was to fortify the Residency, his political and administrative headquarters. The Residency was actually part of a complex of detached buildings that included a banqueting hall, post office, treasury, storerooms, and individual houses. Many of the existing structures had been built by the Nawabs of Oudh and were meant for royal pleasures or ceremonial occasions. None of the buildings had been erected for military purposes. The compound was located on higher ground near the Gumti River, with Lucknow, a sprawling metropolis of 600,000 souls, spread out beneath it.

Necessity was truly the mother of invention, and gradually a defensive perimeter took shape that was roughly pentagonal in shape. There were at least 28 buildings in the compound, of which perhaps a half dozen or so were vital to the coming defense. Entrenchments were dug, mounds of earth piled up, and gun batteries established. There were simply too many buildings to defend, so many of the outlying structures were pulled down, partly to provide a better field of fire for the defenders and partly to prevent insurgents from using them as cover.

Several formerly private residences within the Residency compound were converted into strongpoints. One example was Anderson’s Post, the home of Captain R.F. Anderson of the 25th Native Infantry. Anderson pulled down a garden wall and in its place dug a moat-like ditch that was filled with a prickly hedge of pointed bamboo sticks. A wooden stockade and a mound of earth completed Anderson’s defenses.

Germon’s Post was another key point, formerly the Judicial Commissioner’s office. It was defended by Captain R.C. Germon and his loyal sepoys from the 13th Native Infantry, supplemented by junior civil servants. These civilians, essentially volunteers, also had their families sheltering there.

The post was a two-story building largely built of red brick, like many in the compound. The house itself was barricaded on all sides with boxes and furniture, and a wall of earth was supplemented by fascines, rough bundles of brushwood bound together.

Two batteries, one in the north, and one in toward the south, provided much needed firepower. The half-moon-shaped Redan Battery, which boasted two 18-pounders and a 9-pounder, was named after a famous battery in the recently concluded Crimean War. In contrast, the Cawnpore Battery consisted of an 18-pounder and two 9-pounders. The Cawnpore Battery, which was in a dangerously exposed position, depended on flanking fire from the Martiniere Post and Brigade Mess to be tenable. Indeed, the Cawnpore Battery was considered so dangerous it was relieved daily by a captain and men of the 32nd Foot.

The Residency building was the heart of the defense. It was a three-story brick building with a main entrance that featured a beautiful double-columned portico. The roof boasted an Italianate balustrade, and the façade’s large picture windows were shaded from the harsh Indian sun by elegant venetian blinds. But these features were meant to impress and to provide comfort, not for military considerations.

Converting a small palace into a makeshift fort was no easy task. Large stacks of firewood were arranged into a semicircle to protect the front of the building. The wooden wall formed an embankment about five feet high, with embrasures cut into it for 4-pounders. The rampart was strengthened by mounds of dirt, which gave the illusion that it was of a more solid construction that it really was.

By the end of May, Lawrence thought it advisable to call in all European families from outlying areas and have them shelter in the Residency compound for safety. This made sense but resulted in instances of terrible overcrowding. When their Indian servants eventually ran away, the women would get a taste of real hardship.

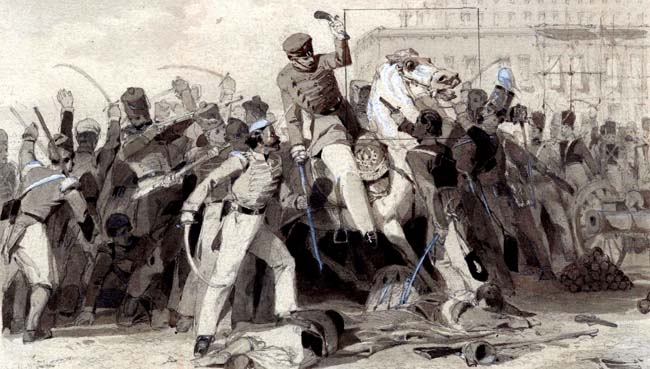

The long-anticipated mutiny at Lucknow began on May 30. It unfolded when sepoys, mainly from the 72nd Native Infantry, finally rose up against the British East India Company. They set fire to the European quarters and killed several British officers foolish enough, or perhaps unlucky enough, to be in the immediate vicinity. Lawrence gathered enough men to confront them; after some desultory fighting, the mutineers were expelled from Lucknow. They would not return in force for another month.

Martial law had been declared, and a number of mutineers had been captured. The prisoners were put on trial; if evidence was lacking, the suspects were released. The few found guilty were promptly hanged.

Goaded by Financial Commissioner Martin Gubbins, who insisted inaction was tantamount to cowardice, Lawrence decided to take the offensive on the last day of June. It was an ill-planned, ham-fisted affair and nearly led to disaster. It began when word was received that a body of rebels were at Chinhat, only eight miles from Lucknow.

Lawrence left Lucknow with a small force composed of 300 men of the 32nd Foot, 230 loyal sepoys, 100 Sikhs, and a small detachment of civilian volunteer cavalrymen. One of the horsemen was a Calcutta businessman named L.E. Ruutz-Rees, who left one of the more compelling and candid memoirs of the mutiny period. It was Ruutz-Rees who gave a detailed account of the Chinhat confrontation.

The advance to Chinhat was badly managed, with the troops marching when the sun was already high and blazing down with full intensity. Indian water carriers quickly decamped when they felt the insurgents were nearby, which did not help the column’s growing needs. Lawrence’s column also marched out without adequate food, and hunger was added to the tormenting thirst.

The Indian insurgent forces, led by the skillful commander General Barhat Ahmed, numbered 5,000 and were supported by 10 guns. The Lawrence column also had artillery, and British guns were unlimbered to start an artillery duel. The 32nd Foot also advanced, boldly exchanging musket fire with the insurgents

But suddenly things began to fall apart. Indian artillerymen and a native police unit deserted to the mutineers, and some began firing at their former employers. The British attack faltered, in part due to the extreme heat and lack of water. The Lawrence column fell back, but the orderly retreat soon turned into a rout.

Lawrence was emotionally devastated by the massive defeat. “My God!” a soldier heard him exclaim. “And I have brought them to this!” The British had brought along an 8-inch howitzer nicknamed “The Turk,” and the massive gun was pulled by an elephant. When things started going bad the elephant handlers cut the traces and took off with the pachyderm, leaving the howitzer behind. It was captured by the insurgents, who made good use of it during the coming weeks.

During that anxious time it seemed that British rule in India was coming to a swift and abrupt end. The first week of June saw rebellions erupt in Sitapur, Faizabad, Sultanpur, and Salon. The entire province of Oudh was now in rebel hands, with British authority reduced to the tiny patch of ground around the Residency.

In the end the important princely states of Hyderabad, Mysore, Travancore, and Kasmir decided to stay out of the insurrection. The smaller states of the Rajputana also stayed neutral. The Sikhs of the Punjab—who had little love for Hindus or Muslims—actively helped the British. They had a warrior tradition and were among the best soldiers the subcontinent ever produced, so their aid was crucial.

But these developments had little immediate effect on the Lucknow siege. The defenders hoped and literally prayed for relief, but the mutineers were a well trained and powerful enemy. It would be some time before the British could mount a counteroffensive that would have any chance of succeeding. The only thing the Lucknow defenders could do was hope for the best while preparing for the worst.

When the siege began there were slightly fewer than 3,000 people at the Residency. There were 1,720 armed defenders, a number that included British soldiers, loyal sepoys, and civilian volunteers. They would provide the backbone of the defense. But a detailed tally included 237 women, 260 children, 50 boys from the Martiniere College, 27 non-combatant Europeans, and 700 noncombatant Indians.

The 32nd Regiment of Foot was the only full-strength European formation at Lucknow when the disturbances began. A weak company of the 84th Foot was also on hand. The traditional red coat was still worn on active service, but more and more it was being replaced by khaki. The men of the 32nd wore summer khaki shell jackets and blue trousers. A Kilmarnock round cap, complete with cover and curtain to protect the back of the neck from the sun, completed the uniform. Ironically, the 32nd was armed with the model 1842 percussion musket, not the more accurate Enfield rifle-musket, the gun that sparked the mutiny.

The civilians were whipped into martial shape during the relative lull that occurred in June. A sergeant of the 32nd Foot was assigned as drillmaster, but most of the men were junior civil servants or businessmen who were not used to using firearms. In the early stages of the siege they often missed targets when the insurgents launched attacks. As the weeks went on, those who survived death by wounds or disease did seem to get better as soldiers; hard lessons were learned by a literal baptism of fire.

Perhaps the most unusual Residency recruits during the siege were boys from the Martiniere School. The student body consisted of European and Eurasian boys, and the school had a sterling reputation. School Principal Schilling, six masters, and 67 boys made their way into the Residency on June 18. The younger boys rode elephants while the older boys formed a rear guard and were armed with muskets.

Any boy capable of bearing arms was given a musket and some rudimentary training on how to use it. The armed recruits were between the ages of nine and 15. But the boys also did a variety of tasks, including tending the sick and wounded, washing clothes, bearing messages, and working the punkah fans. Some of these jobs were usually assigned to Indian servants, almost all of whom fled.

The insurgents began the month of July with a furious bombardment, a veritable hurricane of shot and shell. It was determined that the Machi Bhawan, the dilapidated fortress about three-quarters of a mile from the Residency, could not be held given the large numbers of casualties sustained in the Chinhat fiasco. There was too much enemy gunfire for runners to be sent to the old fort, so a makeshift semaphore was constructed on the Residency roof. It was said that the Martiniere boys had a hand it its design and operation.

After one or two abortive attempts the semaphore did manage to convey the message: spike the guns, blow up the fort, and retire to the Residency at midnight. As midnight approached, Colonel Palmer opened the gates and began the trek to the Residency. Luck was with them, and their 15-minute journey was undetected by the insurgents. After their safe arrival, a slow-burning fuse reached the 240 barrels of powder and 594,000 cartridges and blew them up with a deafening roar. It was a cataclysmic blast that shook Regency buildings and blew out many windows.

It was soon discovered that the buildings were still largely unsafe, in spite of all the sweat and toil that had gone into transforming them into makeshift fortresses. On July 2 a shell crashed into the Residency’s second floor, tearing off the leg of 19-year-old Suzanna Palmer, who was said to be engaged to a company officer. Palmer and a few other women had elected to stay on the second floor, probably because the lower rooms were crowded and stifling almost to the point of suffocation.

Palmer begged medical staff not to remove what remained of her leg, but Dr. Joseph Fayrer insisted, and the operation proceeded. The young woman died in great pain two days later. She was the first civilian casualty, and a foretaste of what was to come. Lawrence had a near miss a day earlier, when an 8-inch shell crashed through a window and landed in a room where he and his staff were staying. The shell failed to detonate, and the commissioner downplayed the incident to his staffers.

Tragedy struck the next day. Weary after long hours of inspections, Lawrence finally decided to take a break by lying down on a bed on the Residency’s second floor. While the commissioner was resting, Captain Thomas Wilson stood nearby reading a report to him.

Suddenly the room dissolved into sheets of smoke and flame, the blast accompanied by a deafening roar. An 8-inch shell had once again crashed through, but this time it detonated and mortally wounded Lawrence. A shell fragment smashed the upper part of his thigh and fractured his pelvis. A tourniquet staunched the blood flow, but little else could be done for him.

The commissioner appointed Major John Banks as his political successor and tapped Lt. Col. John Inglis to take care of military affairs. He was given chloroform to ease his pain, but infection must have set in because his agony grew more intense with each passing hour. Some were unnerved by his tormented moans and piercing screams of agony, and after much suffering he died two days later.

Though forgotten in most histories, the British had a formidable Lucknow opponent in Begum Hazrat Mahal, wife of the deposed Nawab. She was known for her beauty, but also for her efficient rule and keen intelligence. A kind of Indian Boudica, she was a politically savvy warrior queen with a sound strategic sense. Her fiery speeches inspired her soldiers, and it was said she actually led them in battle.

The day after Lawrence died the Residency defenders could hear music and festive noise coming from the city proper. The Begum was in the process of installing her son, Birjis Qadar, as the new Nawab of Oudh. Since the lad was only 12, the Begum continued to hold power as a kind of regent.

The European women fought their own battles, conflicts of a more immediate and personal nature. Hour after hour, day after day, week after week, they grappled with terror and despair, with little more than their own courage and religious faith to sustain them. Katherine Bartum found herself assigned to the ironically titled “Ladies Quarters,” which she describes as dirty and uninviting. Initially, she and her two-year-old son were crowded into one room along with 15 other women and children.

Bartum’s diary details her struggle to keep her son alive as conditions worsened and unsanitary living conditions spread disease. Some of the women and children contracted cholera; there also were outbreaks of smallpox. She recorded her emotional ups and downs; for example, chronicling how her son survived dysentery and a near-fatal fever.

No place was really safe. Bartum was horrified when a little girl she watched playing in the courtyard was suddenly hit in the head by a cannonball. She fainted from the sheer shock of seeing such a bloody demise, but in time such scenes of death and destruction grew commonplace. The noncombatant casualties mounted, rivaling the number of male battle deaths.

In some respects the women did have the worst of it. Once the fighting began, the terror was amplified by the fact that they were literally and figuratively in the dark. The underground rooms, known as tykhanna, had little or no natural light. “There would come the cry of all lights out; the children would cry at being in the dark, and the women would be trembling in fear lest the enemy attack proved successful and the sepoys should get in,” recalled Bartrum.

Sounds of battle would filter into the rooms, a chaotic cacophony that included the crash of shells and rattle of musketry, the screams of the wounded, and the shouts and cries of men engaged in the fight of their lives. Women never knew if a door would suddenly open and mutineers might rush in to kill all inside.

By mid-July the Residency compound was reeking with a sickening stench, an amalgam of smells from human waste and the decomposing bodies of men and animals. During lulls in the fighting the musket was exchanged for a shovel as every effort was made to bury the decaying flesh before pestilence spread. The work was exhausting in the innervating heat and only partly successful. Many of the graves were so shallow that the reeking cemetery was avoided as much as possible.

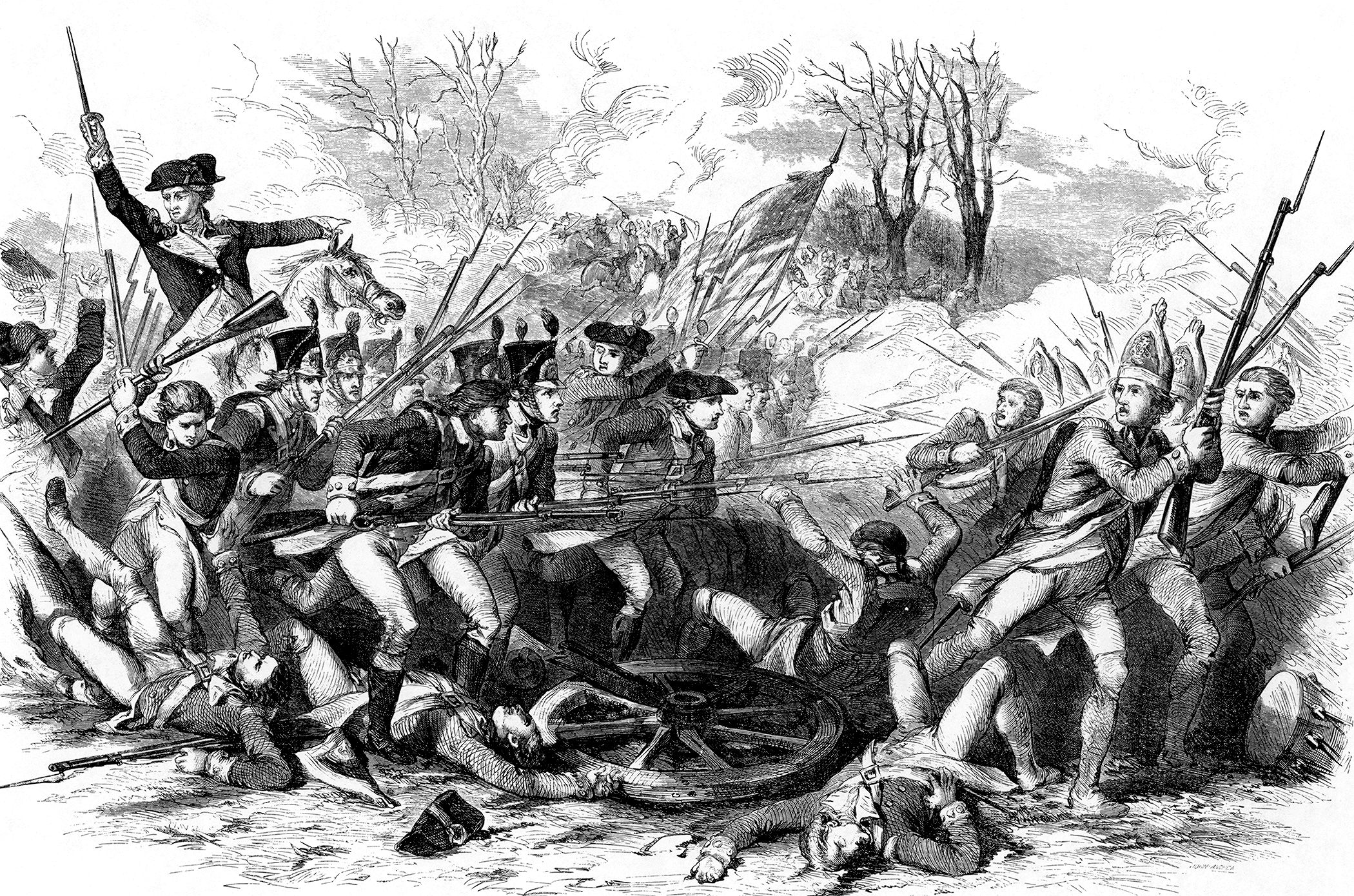

The insurgents launched an all-out assault on July 20. Ruutz-Rees was busy cleaning his musket when suddenly the loud cry of “To Arms!” caused him to pause in his labors. Large numbers of rebels had been seen massing, so every man had to report to his post. Ruutz-Rees started running out of the building when an explosion erupted near the Redan, a blast so powerful the ground beneath his feet shook.

The insurgents had tunneled underground and planted a mine in hopes of blowing up the Redan. Once a breech in the fortifications was deemed practicable, the insurgents hoped to pour into the Residency compound before the defenders could respond; however, the mutineers had miscalculated, and the Redan was intact. The smoke from the explosion obscured the battery, and the insurgents were not aware of their error until the attack was well underway.

The Redan’s guns opened up as soon as the enemy was in range, discharging lethal blasts of grapeshot that shredded and lacerated the oncoming ranks. The rebels paused at the Redan but soon renewed their attacks at other posts. Gubbins’ post was one of their targets, a building so battered by days of artillery fire that its upper story was reduced to a shattered, pock-marked ruin.

Sensing an opportunity, insurgent sepoys climbed into the Gubbins building to engage the defenders. They were bayoneted for their trouble, and swarming groups of insurgents just below were kept at bay by hand grenades. Lieutenant Gregor Grant proved particularly adept at lobbing grenades but handled one whose fuse was so short it exploded prematurely. The lieutenant’s hand was blown off, and a nearby officer was wounded. Grant’s hand was amputated, but he died from the effects of the wound.

Some of the heaviest fighting that torrid July day came from around the area on the Innes post, a house on the northwest side of the compound once owned by Lieutenant McLeod Innes. A mixed group defended the post, including loyal sepoys of the 13th Native Infantry, some soldiers of the 32nd Foot, and civilian volunteers such as Ruutz-Rees.

At one point Ruutz-Rees recalled, “Our men, seeing the rebels swarming thick as bees, and nothing but one sea of heads and glittering weapons before them, thought of retreat.” The commander of this post was Lieutenant Loughnan of the 32nd Foot. “Give a shout, my boys, a loud and strong one!” he said. The men complied, lustily yelling with all of their might, “Hurrah! Hurrah! Hurrah!”

The insurgents, almost as if on cue, suddenly stopped dead in their tracks. It seems the mutineers thought that the long awaited relief column had finally arrived. The column had not arrived, but the pause gave the defenders renewed courage and perhaps a laugh. Momentarily checked, the rebel advance began again, and some managed to get to the base of a wall where the defenders’ gunfire could not reach them.

Insurgent attacks were accompanied by drums, bugle calls, and fierce exhortations by their leaders to kill the Europeans. Yet in all the excitement they had forgotten to bring scaling ladders. “Bring the ladders!” the insurgents shouted in their native tongue over the din of battle. Parties of three brought scaling ladders, but in so doing they came within range of defender muskets.

The soldiers and civilians poured a surprisingly accurate fire on the ladder bearers, and as one fell dead or wounded, the other two dropped their burden and retreated with their stricken comrade. The scaling parties decided to forego the use of ladders and simply climb the ramparts. Some of them did succeed in getting to the top but were quickly bayoneted for their trouble.

Since the Innis post defenders lacked hand grenades, and numbers of insurgents still huddled at the base of the wall, they improvised a solution. They threw bricks and mortar and other missiles of an impure nature—perhaps bottles of urine or beef entrails—at the heads of their attackers and quickly dislodged them.

As July turned to August hopes for relief started to fade. “As for death it stares one constantly in the face,” wrote Ruutz-Rees. “Not daily, not hourly, but minute after minute, second after second, my life, and every other’s, is in jeopardy. Balls fall at our feet, and we continue the conversation without a remark; bullets graze our very hair, and we never speak of them.”

There was enough food to stave off starvation, but nothing more. Bartum recalled the rations included flour, rice, peas, salt, and meat. Rees noted in his dairy that the beef ration was usually studded with flies. “These scamps flew into my mouth, or tumble into the plate, and float about in it, impromptu peppercorns,” he wrote.

In the underground rooms, conditions grew worse by the day. Vermin multiplied, and women and children crawled with lice, which the women called “light infantry.” Rats and mice scurried about, and at night their scampering over faces interrupted many a victim’s fitful sleep. By July the monsoon season was in full swing, but the rains brought more misery than comfort. The air might momentarily freshen, but then the dampness produced a stultifying humidity that sapped strength and weakened resolve.

August was ruefully dubbed the “Month of Mines” because the insurgents persisted in trying to blow up the defenders with subterranean explosives. Men on sentry duty were told to listen for the sounds of digging, and it got so that enemy tunneling became kind of a grim joke. “So hurrah, my friend, for a celestial trip in the air!” as one defender laughingly told Ruutz-Rees.

survivors to safety.

The defenders were fortunate to have a resourceful engineer in their midst. Captain Peter Fulton sought out enemy tunnels before they could be finished and planted with mines, a job he performed with considerable success. The defenders dug shafts as deep as 30 feet. After that, they tunneled horizontally to carve out galleries in the direction of the enemy’s tunnels. Luckily, the soil in the Lucknow area was firm, so little or no shoring up was needed, and the tunnels were short enough not to need ventilation.

Accompanied by a devoted Sikh assistant who carried blasting powder, Fulton would find insurgent tunnels then blow them up. One time he actually broke into a rebel tunnel while the workers were digging. The sudden appearance of the Englishman so surprised the enemy miners that they fled immediately. It was also fortunate that the 32nd Foot hailed from Cornwall because the men had ample experience in mining in their native region.

The long-awaited rescue came on September 27 when a relief column under Maj. Gen. Henry Havelock and Maj. Gen. James Outram arrived in Lucknow. It had been more than 12 weeks since the siege began, and the defenders were beginning to lose hope. The doors of the battered Bailey Guard Gate, entrance to the Residency compound, were thrown open to allow the Highlanders, Madras Fusiliers, and turbaned Sikhs to enter.

“Oh, what welcome! What joy!” exclaimed defender Henry Metcalfe. “Comrades shaking hands … and rough soldiers embracing and kissing little ones.” The elation was genuine, but the rescue was more apparent than real.

A third of the relief force had been killed or wounded during the arduous march, and soon the British found they did not have enough men to fully break the siege. The relief force ended up reinforcing the original garrison but little more. The first siege had lasted 87 days; the second would be another 61 days.

The Lucknow Residency was finally relieved in November 1857 by troops under Lt. Gen. Sir Colin Campbell. Not wanting to be trapped as his predecessor Havelock had been, Campbell evacuated the Residency in a general retreat that took place over several days. The mutineers were not even aware of the withdrawal until it was too late. The British returned to Lucknow the following year.

The British Union Jack British had flown day and night during the siege, shot torn and tattered, but still defying its enemies. As a special dispensation, unique in the British Empire, a British flag continued to fly there until Indian independence in 1947.