By Don Hollway

In the face of disaster, few military commanders in history maintained the British stiff upper lip as well as Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington. In mid-June 1815 he attended a ball given by Charlotte Lennox, Duchess of Richmond, in her Brussels home. Her guest list included all the highest nobility and military commanders of the city: Prince William of Orange-Nassau; Frederick, Duke of Brunswick; Lt. Gen. Sir Thomas Picton; right down to 18-year-old Lord James Hay, heir to the Earl of Erroll. “With the exception of three generals, every officer high in the army was to be there seen,” wrote Lady Katherine Arden, daughter of Richard, Baron Alvanley.

If the Richmond home was practically a military headquarters, it was with good reason. In March Napoleon Bonaparte, the former Emperor of France and would-be conqueror of Europe, had escaped exile on Elba. From the Mediterranean to Paris, the heart of Europe rang once more with cries of “Vive l’Empereur!” And that very day reports indicated that France’s 130,000-strong Army of the North had invaded Belgium.

“When the Duke [of Wellington] arrived, rather late, to the ball I was dancing, but I went to him to ask about the rumours,” wrote the duchess’s 17-year-old daughter, Georgiana. “He said very gravely, ‘Yes, they are true; we are off to-morrow.’” As supreme commander of the combined armies of England and the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, which at the time included modern Holland, Belgium, and Luxembourg, Wellington would face death in the days ahead. But that was no reason for him to miss the duchess’s ball that evening.

Guests arrived into the night. Colorful gowns and resplendent uniforms swirled across the ballroom floor. The Gordon Highlanders performed a sword dance and reels. Around midnight a messenger arrived with urgent news. Wellington conferred with Prince William, who begged leave to depart. One by one the other officers also began slipping away. “Those who had brothers and sons to be engaged openly gave way to their grief, as the last parting of many took place at this most terrible ball,” wrote Lady Katherine.

Sitting beside Lady Georgiana, Wellington indulged in food and conversation until around 1:30 amand then retired to his guest quarters. Before taking leave he inquired of his hosts if there was a good map in the house. In the study, behind closed doors, he compared field reports to the terrain. The duke had won fame in the Spanish Peninsula as a master of defensive tactics who had fought in nearly 60 battles and never lost; however, he had never fought Bonaparte. He had cantoned the Anglo-Dutch army to the southwest, around Nivelles, to protect his supply line from England, but the French had taken Charleroi, due south, and were just 13 miles from Brussels. “Napoleon has humbugged me, by God; he has gained 24 hours march on me,” Wellington famously declared.

Across the border, another great general was also trying to keep up with Bonaparte. Marshal of France Michel Ney had risen from the ranks in every major battle his country fought, from Valmy in 1792 to Leipzig in 1813. He had commanded the French rear guard on the retreat from Moscow, even though at one point completely it was cut off from the main army. At the final escape across the Beresina River he became renowned as “the last Frenchman on Russian soil.” His men knew him as Le Rougeaud for his ruddy complexion and fiery disposition. Napoleon himself called Ney the “Bravest of the Brave.” He had promoted Ney to Marshal of France and titled him Prince of Moscow.

Yet it had been Ney who, after the surrender of Paris, led the Revolt of the Marshals, refusing to fight on. What is more, when Napoleon went off to exile on Elba Ney joined the royalists. But on Bonaparte’s return, it was Ney whom fat, gouty King Louis XVIII sent to bring him to heel. “Sire, I hope I shall soon be in a position to bring him back in an iron cage,” said Ney.

Ney stormed south but along the way lost his resolve and his royalism. “Embrace me, my dear Ney,” Napoleon told him at their meeting. “I am glad to see you. I want no explanations. My arms are ever open to receive you, for to me you are still the bravest of the brave.” Ney changed sides again, and so did France. On March 19, Louis fled the country, and less than 24 hours later Napoleon rode into Paris.

Austria, Russia, and Prussia agreed to contribute 150,000 men each alongside the English, Dutch, and Belgians, a Seventh Coalition to crush Napoleonic aspirations once and for all. “Thus France was to be attacked in the course of July by six hundred thousand enemies,” wrote Bonaparte’s aide-de-camp, General Gaspard Gourgaud. “But, at the beginning of June, only the armies of Generals [Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von] Blucher and Wellington could be considered as prepared for action. After deducting the troops, which it was necessary they should leave in their fortresses, they presented a disposable force of two hundred thousand men on the frontiers.”

But Napoleon intended neither to wait for the Allies to invade France nor fight them all at once. Preparation for war went on without Ney, who for six weeks awaited a command. “Send for Marshal Ney and tell him that if he wishes to be present at the first battles, he ought to be at Avesnes on the 14th,” Napoleon ordered on June 11. “My headquarters will be there.”

Ney and his aide-de-camp, Colonel Pierre-Agathe Heymes, arrived in Avesnes-sur-Helpe, on the Belgian border, on the evening of June 13. Forced to scrounge horses and places to sleep, they tagged along with the army like camp followers as it moved up. Before dawn on June 15, the II Corps under General Honore Charles Reille, supported by I Corps under General Jean-Baptiste Drouet, Count d’Erlon, crossed the border and pushed a Prussian battalion out of Charleroi. By noon nothing lay between Bonaparte and Brussels. He finally summoned Ney to his headquarters and revealed his battle plan.

The emperor expected impetuous Blucher to attack from the east, where Napoleon would knock him out of the war with his main force. All Ney had to do was prevent Wellington from coming to the Prussians’ aid until Bonaparte wheeled about. Together they would defeat the Anglo-Dutch in turn. The Allies would sue for peace before Austria and Russia even entered the fight. “Take command of the 1st and 2nd army corps,” Napoleon told Ney. “I am giving you also the light cavalry of my Guard, but don’t use it yet. Tomorrow you will be joined by [cavalry general François Etienne de] Kellermann’s Cuirassiers. Go and drive the enemy back along the Brussels road and take up a position at Quatre Bras.”

Quatre Bras, which means four arms, was a farm hamlet 10 miles north of Charleroi, where the road to Brussels crossed the route from Nivelles to Namur. By holding it, Ney would block Wellington’s path to Blucher. “Depend on it,” Ney assured Napoleon. “In two hours we shall be at Quatre Bras, unless all of the enemy’s army be there!” And with the same martial spirit he had shown his king, he hurried off in the service of his emperor. “But he forgot that there is nothing worse for a general than to take command of an army the day before a battle,” wrote Heymes.

Ney caught up with Reille’s II Corps at Gosselies, about seven miles short of Quatre Bras. With several hours of daylight left, he called upon the Guards Light Cavalry Division under General Charles Lefebvre-Desnoettes to follow him up the Brussels road to Frasnes, halfway to their objective. When they topped a rise overlooking the village, they came under cannon fire. A battery of horse artillery and a battalion of troops held the town.

Two squadrons of the 2nd Light Horse Regiment of Lancers of the Imperial Guard, General Pierre David de Colbert-Chabanais’s famous Red Lancers, rode around Frasnes in full view of the defenders. “As they observed that we were maneuvering to turn them, they retired from the village where we had practically surrounded them with our squadrons,” wrote Lefebvre-Desnoettes.

The enemy fell back not to the east, but to the north. These were not Prussian troops. They were Dutch: the 2nd Battalion, 2nd Nassau-Usingen Brigade, and the 2nd Netherlands Infantry Division. They withdrew toward Quatre Bras, knowing the entire brigade, four battalions under Colonel Prince Bernhard von Saxe-Weimar, was coming down the Brussels road.

“General Colbert even reached within musket shot of Quatre Bras on the high road, but … it was impossible for us to carry it,” wrote Lefebvre-Desnoettes. The Red Lancers spotted the main body of Netherlanders descending on them. Colbert elected not to take on the entire brigade himself but abandoned the town and rode back to Frasnes. By 7 pm,Saxe-Weimar had 4,500 men and six cannons in Quatre Bras.

Given a few more hours, Ney might have organized two divisions to clear the town in a night assault. But the 17,800 men of II Corps were strung out halfway back to France. The 5th Infantry Division under Brig. Gen. Gilbert Desire Joseph, Baron Bachelu, was at Frasnes, 21/2miles to the rear. The 9th Infantry Division under General Maximilien Sebastien, Count Foy, and the 6th Infantry Division under Napoleon’s younger brother, Prince Jerome Bonaparte, were twice as far back, in Gosselies. And d’Erlon’s entire I Corps was still farther south, around Charleroi. Bringing them all up via the one road to Frasnes by night would be quite the exercise in traffic control. With the troops available Heymes estimated they had not one chance in 10 of taking Frasnes before dawn.

So Ney prepared to carry out his orders in the morning. Meanwhile, Wellington’s commanders disobeyed his orders. Overnight, Saxe-Weimar sent word up the road to Nivelles, alerting his division commander, Lt. Gen. Henri Georges, Baron Perponcher-Sedlintsky, of the French invasion. They elected to ignore Wellington’s command to concentrate at Nivelles and to fight instead at Quatre Bras.

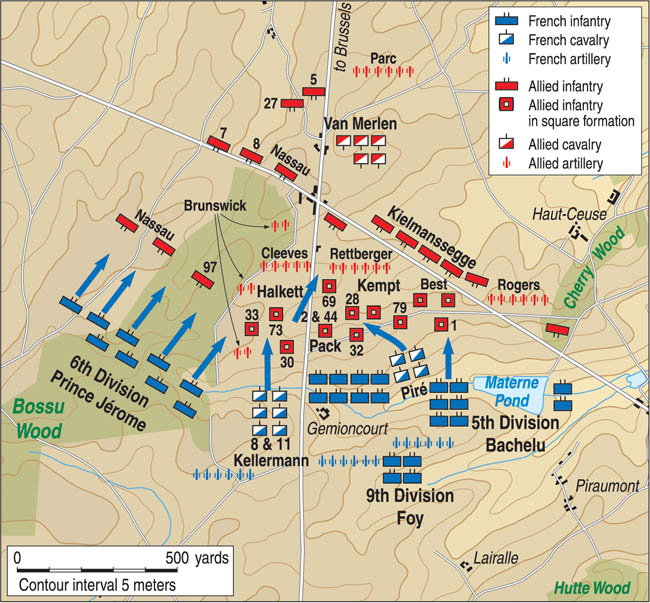

The battlefield was a rough triangle, pointed upward, with the crossroads at its apex. The Bossu Wood stretched southwest, offering cover for defenders and attackers alike. Likewise, the Namur road led through a defile to the southeast, past the village of Piraumont, toward Ligny and the Prussians. The Brussels-Charleroi road ran up the middle, across a shallow, rolling valley full of undulations and folds of dead ground carpeted with tall fields of wheat, corn, barley, and rye. Centered in the triangle was a large farmstead, Gemioncourt, which consisted of several buildings and a courtyard enclosed by brick walls, a natural fortress commanding the field. Perponcher and Prince William of Orange-Nassau, arriving before sun up with reinforcements, intended to hold it all with just 8,000 infantry and 16 guns.

“The enemy showed many men outside the wood, around the houses of Quatre Bras and on the Namur road,” wrote Count Foy. Ney’s command totaled nearly 50,000 men, but by noon he had on hand only two divisions of Reille’s II Corps, about 10,000 foot, 2,000 horse, and 30 guns. Ney, Foy, and Reille had all fought Wellington on the Peninsula and well remembered the duke’s use of terrain to mask his true strength. “Reille thought that this might well be like a battle in Spain, where the English troops would only show themselves when it was the right time and that it was necessary to wait and only start the attack when everyone was concentrated and massed on the ground,” wrote Foy.

Wellington, who had arrived around 10:00 am, as yet had no reinforcements to hide but saw only a small force of French troops opposing him, their mere presence requiring the English and Dutch to block their way. He took the opportunity to ride down the Namur road to meet Blucher. “If, as seems likely, the division of the enemy’s forces posted at Frasnes, opposite Quatre Bras, is inconsiderable, and only intended to mask the English army, I can employ my whole strength in support of the Field-Marshal, and will gladly execute all his wishes in regard to joint operations,” wrote Wellington.

At Ligny, Napoleon was preparing to attack the Prussians when a messenger arrived from Ney advising that the Allies were massing in Quatre Bras. The emperor had thought the town already in French hands. He immediately fired off fresh orders, in writing and in the strongest terms. “Concentrate the corps of Counts Reille and d’Erlon and that of Count [François Etienne de Kellermann, 2nd Duke de] Valmy, who is just marching to join you. With these forces you must engage and destroy all enemy forces that present themselves.”

D’Erlon’s corps was still far to the rear. “One o’clock came, and still the first corps did not arrive,” wrote Heymes. “There were no tidings of it, yet it could not be very distant. The marshal therefore did not hesitate to begin the battle.”

At Ligny, Wellington and Blucher had climbed up into a windmill from which they could see through a telescope innumerable French troops gathering and even Napoleon himself. They concluded the main battle would be there, and that only a token force faced Wellington. The duke agreed to come to the Prussians’ aid, but as he and his party headed back up the road they could hear cannon fire at Quatre Bras.

Ney’s opening barrage forced back the scant Dutch batteries around Gemioncourt. With that, hundreds of French skirmishers, tirailleurs, poured down into the man-high grain fields. Their counterparts in Lt. Col. Johann Grunebosch’s 27th Dutch Jäger Battalion withstood them only briefly. An Allied soldier on the campaign remembered the enemy sharpshooters well. “Their fine, long, light firelocks, with a small bore [the .69-caliber Charleville musket], are more efficient for skirmishing than our abominably clumsy machine [the .75-caliber India Pattern Brown Bess],” wrote the soldier. “The French soldiers, whipping in the cartridge, give the butt of the piece a jerk or two on the ground, which supersedes the use of the ramrod; and thus they fire twice for our once…. It was astonishing to find how galling the fire of the enemy proved to be, and how many men we lost.”

As the jägers fell back at 2:30 pm, Ney launched his main assault. On the right, 4,300 men of Bachelu’s division advanced on Piraumont and the key Namur road. In the center, 5,500 men of Foy’s division started up the Brussels road directly toward Quatre Bras. In the face of such numbers Grunebosch’s 750 jaegers fell back on Gemioncourt. French snipers harassed them all the way, targeting enemy officers and horses.

Perponcher ordered Lt. Col. Jan Westenberg’s 5th Dutch Militia Battalion into the fray. Only about 20 of its 450 men had ever seen action. They immediately received the full attention of the French artillery and, out in the high corn around the farmstead, hidden tirailleurs. They fell back in disarray. French cavalry commander Lt. Gen. Hippolyte Pire unleashed the chasseurs and lancers of his 2nd Cavalry Division on them. The rattled young militiamen barely responded in time. “After we had formed square, we noticed that some men from one company or platoon were mixed with those of other companies and wanted to restore proper order, then Lieutenant-Colonel Westenberg told us we did not have to be so precise,” wrote one soldier.

The French horsemen launched four separate attacks but, confronted with a hedge of enemy bayonets and coming under direct cannon fire, were unable to break the Dutch square. Behind them, Foy’s division had bogged down in soft ground and high grain, and without infantry support Pire’s cavaliers were obliged to fall back.

On the right, though, Bachelu’s division found Piraumont undefended and the Namur road within their grasp. They even came within moments of capturing a small party of horsemen that included Wellington himself, on his way back from meeting Blucher. “By God if I had come up five minutes later the battle was lost, but I had just time to save it,” wrote the duke.

Across the field, at about 3 pm, Ney welcomed reinforcements. Prince Jerome’s 8,000 men of II Corps’ 6th Infantry Division, the largest in the Armée du Nord, brought the French forces to almost 20,000 infantry, 4,500 cavalry, and 50 guns. And fresh word arrived from Ligny, where Bonaparte was having a harder fight than expected. “His Majesty’s intent is that you should attack all that is in front of you, and that, after having vigorously pushed it back, you should advance toward us to assist in enveloping [the Prussians],” wrote Marshal Jean-de-Dieu Soult.

On the French left, Jerome assaulted the Bossu Wood. Tactics were impossible in the tangled undergrowth formation. The prince, more renowned as a socialite than a soldier, personally led the attack. “Prince Jerome was struck on the hip, but fortunately the ball hit the big gold scabbard of his sword first and did not penetrate, so he suffered nothing worse than a severe bruise which made him turn pale,” wrote his aide-de-camp, Captain Bourdo de Vatry. “Conquering his pain, the Prince remained on horseback at the head of his division, thereby setting for us all an example of courage and self-sacrifice. His coolness had an excellent effect.” With three times the manpower, the French cleared all but the northern edge of the forest. A number of tirailleurs reached the Nivelles road behind it, threatening the Allied rear.

In the center, Foy’s division used five-to-one odds to compel the Netherlanders to abandon Gemioncourt. The Prince of Orange-Nassau took it upon himself to lead a desperate counterattack. Waving his hat overhead, William led the remnants of the 5th Battalion and 27th Jägers forward, but the French now held the farmstead in strength and hurled them back with heavy casualties. Again Pire sent his cavalry among the disorganized infantrymen. Grunebosch’s horse was felled by a French cannonball. He continued the fight on foot, but a French sabreur slashed him about the head and arm, knocking him out of the battle.

At last the Dutch cavalry arrived. Maj. Gen. Baron Jean-Baptiste van Merlen, an ex-officer of Napoleon’s imperial guard, ordered his 6th Dutch Hussar Regiment to the rescue. Having just arrived after a nine-hour ride, the hussars launched a hasty, ill-formed charge, easily repulsed by Pire’s horsemen. The Prince of Orange-Nassau was nearly captured, breaking out of a knot of French cavaliers to the safety of a square formed by the 7th Belgian Line Battalion. He gave their color bearer the embroidered star of the Military Order of William, torn from his own breast, saying, “My brave Belgians, take it, you have won it fairly. You have deserved it!”

Having all but ridden into Quatre Bras, Pire’s cavalry was overextended, disordered, and vulnerable to counterattack. All the Dutch had left was van Merlen’s 5th Belgian Light Dragoons Regiment. A quarter of their riders, including many of the officers, had previously served under Napoleon. Old friends recognized each other in opposite ranks, and several Frenchmen cried, “To us, Belgians, to us!” But the plea went unheeded. The fight devolved into a melee of slashing swords, charges, and countercharges, even more confused since both sides wore green uniforms with yellow trim. Finally, the French 5th Regiment of Lancers arrived to tip the balance. The Belgians broke and fled with the French charging hard after them, about to pursue them all the way into town and win the Battle of Quatre Bras.

Between the horsemen and the crossroads, however, rode the Duke of Wellington on his famous thoroughbred Arabian stallion, Copenhagen. Far from leading a counterattack, the duke wheeled his mount and spurred hard for the safety of the Namur road. And there, from the ditch running alongside, suddenly arose a line of men in bright red uniforms and kilts. These soldiers were the 92nd (Gordon Highlanders) Regiment of Foot. Their guns were raised and their bayonets fixed. The British had arrived.

Legend has it that Wellington called to them, “Lie down, 92nd!” The Highlanders, some of whom had been performing the sword dance for the Duchess of Richmond the previous evening, threw themselves flat, and Copenhagen carried his master over them, bayonets, ditch, and all. “On a worse horse he might not have escaped,” wrote the duke’s aide-de-camp.

It must be said that numerous historians find this story too good to be true and doubt Wellington’s leap happened at this point in the battle, or that it happened at all. “It is not true that the Duke on retiring ‘leaped the bayonets’ of the regiment that lined the hollow roadway,” wrote General Sir George Scovell. “I was with the Duke, and we were retiring before a charge of the enemy’s cavalry, when the Duke cried out ‘Make way men, make way!’ and a passage opened for us.” Accounts by officers of the 92nd mention repeated French cavalry charges but not Wellington’s leap. Nevertheless, the story has passed into Quatre Bras folklore.

The French horsemen thundered right up to the British line. “Lord Wellington, who was by this time in rear of the centre of the Regiment, said, ‘92nd, don’t fire until I tell you,’ and when they came within twenty or thirty paces of us, his Grace gave the order to fire, which killed and wounded an immense number of men and horses, on which they immediately faced about and galloped off,” wrote Lieutenant Robert Winchester of the 92nd Regiment.

Their retreat gave the beleaguered Allies a respite as reinforcements finally poured into Quatre Bras from the north. The reinforcements were the 3,500 men of General Sir Thomas Picton’s 5th Division and 4,500 black-uniformed infantrymen and 900 cavalry under Frederick, Duke of Brunswick. Wellington ordered the British to the east to secure the all-important Namur road and deployed Frederick’s Brunswickers to assist them and the Prince of Orange-Nassau, who was on the verge of losing the Bossu Wood.

“He is a rough, foul-mouthed devil as ever lived, but he always behaved extremely well; no man could do better in the various services which I assigned to him,” wrote Wellington of Picton. Wellington ordered the 1st Battalion, 95th Regiment of Foot out to bolster the Allied extreme left flank, where they took cover in several small farmhouses along the Namur road. “We remained very quietly where we were until the French, bringing up some artillery, began riddling the house with round shot,” wrote Private Edward Costello. “Feeling rather thirsty, I asked a young woman in the place for a little water. She was handing it to me, when a cannon ball passed through the building, knocking the dust about our ears. Strange to say, the girl appeared less alarmed than myself.”

At that point, the 79th Regiment of Foot, the Cameron Highlanders, emerged from the road defile. “The rye was so tall before it was broken down that we could see little more than the Frenchmen’s heads above it,” wrote Private Dixon Vallence. “As we charged, we gave them three Highland hurras, and put them to flight, as fast as their legs could carry them, yelling out the most opprobrious epithets against ‘the men without breeches.’”

The 42nd (Highland) Regiment of Foot, the famous Black Watch, received the order to fix bayonets. “There is something animating to a soldier in the clash of the fixing bayonet; more particularly so when it is thought that the scabbard is not to receive it until it drinks the blood of its foe,” wrote Sergeant James Anton. But no sooner had the 42nd routed the French infantry than the imperial cavalry was on them. The Scots had time to form only a partial square. Armored horsemen swirled around the clumps of Highlanders in the tall grass. Caught out in the open, Lt. Col. Sir Robert Macara, a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath, was wounded and captured. Recognizing the gold epaulettes and embroidered KCB of a high-ranking officer, the French ran a lance point under his chin into his brain.

Regimental command changed hands downward four times in minutes. A ricocheting cannonball clipped Picton himself, who carried on. Finally the musketry, firing over the heads of the ranks kneeling with bayonets up, proved decisive. “Riders cased in heavy armour fell tumbling from their horses; the horses reared, plunged, and fell on the dismounted riders; steel helmets and cuirasses rang against unsheathed sabres as they fell to the ground; shrieks and groans of men, the neighing of horses, and the discharge of musketry rent the air, as men and horses mixed together in one heap of indiscriminate slaughter,” wrote Anton.

Wellington ordered Frederick of Brunswick to fill the gap between the Bossu Wood and Gemioncourt. The Black Duke harbored a notorious grudge against the French, who had incorporated his duchy into a vassal kingdom ruled by Prince Jerome. His black-uniformed mercenaries, with their silver death’s-head badges, had gained a fearsome reputation during the Peninsular War, but in their exposed position the hussars and uhlans took a beating from Jerome’s artillery and tirailleurs. When French infantry advanced, they retreated. Frederick, who had been riding up and down their ranks calmly puffing on his pipe, led a cavalry charge, but a musket ball knocked him off his horse. “The deathly pale of his face and his half-closed eyes indicated the worst,” wrote an eyewitness. The duke was carried to the rear and pronounced dead. “The column of French cavalry that drove back the Brunswickers retired a little, then re-formed, and prepared to charge our regiment; but we took it more coolly than the Brunswickers did,” wrote Sergeant David Robertson of the 92nd Regiment.

Some accounts indicate that this was when Wellington made his leap over the 92nd’s bayonets, but there were so many French cavalry charges that day they were easily confused. “When the Duke of Wellington saw them approach, he ordered our left wing to fire to the right, and the right wing to fire to the left, by which we crossed the fire; and a man and horse affording such a large object for an aim, very few of them escaped. The horses were brought down and the riders, if not killed, were made prisoners,” wrote Sergeant Robertson.

Wellington ordered the 28th (North Gloucestershire) Regiment of Foot to take over for the decimated 42nd. At Alexandria in 1801, the 28th had stood in two ranks, back to back, to shoot down French cavalry, for which they were permitted the honor of wearing the regimental number both on the front and the back of their stovepipe shakos. At Quatre Bras it very nearly came to that. “Once, when threatened on two flanks by what Sir Thomas Picton imagined an overwhelming force, he exclaimed, ‘28th, remember Egypt.’ They cheered and gallantly beat back their assailants, and eventually stood on their position,” wrote Major Richard Llewellyn. Maj. Gen. Sir James Kempt, commanding Picton’s 8th British Brigade, of which the 28th was part, rode before them waving his hat. “Bravo, 28th!” he shouted. “The 28th are still the 28th and their conduct this day will never be forgotten.”

To the east the battle had flowed back and forth over the vital Namur road. French artillery and infantry drove the 95th off it; the British regrouped and pushed the enemy back again. “I was in the act of taking aim at some of our opposing skirmishers, when a ball struck my trigger-finger, tearing it off,” wrote Costello. “On my return to the house at the corner of the lane, I found the pretty girl still in possession, although there were not less than a dozen shot-holes through it. I requested her to leave, but she would not, as her father, she said, had desired her to take care of the house until he returned from Brussels.”

It was about 5 pm. Having taken everything Ney could throw at them, the Anglo-Dutch were exhausted and almost out of ammunition, but now their ranks were replenished by the arrival of 6,000 men of the 3rd Infantry Division under Lt. Gen. Count Carl von Alten. Wellington deployed its British brigade toward the Bossu Wood and its Hanoverian brigade on the left flank. With 25,000 infantry, 2,000 cavalry, and 36 guns, the Allies were ready to push back.

But at Ligny, Bonaparte had the Prussians where he wanted them. He called on Ney to deliver the coup de grace. “You must manoeuvre at once so as to envelop the right of [Blucher] and fall quickly on his rear; this army is lost if you act vigorously; the fate of France is in your hands,” ordered Napoleon. Ney was still awaiting the arrival of d’Erlon with I Corps: some 20,000 men and 50 cannons. But it was almost at this same moment that Ney learned Napoleon had already doomed any victory at Quatre Bras. “The 1st Corps, by the emperor’s order … had left the Brussels road instead of following it, and was moving in the direction of [Ligny],” wrote Heymes. The reinforcements that Ney so desperately required for victory had been marching away from him for over an hour. “The shock which this intelligence gave me, confounded me,” Ney testified after the war.

Ney immediately sent counter orders for d’Erlon to rejoin him, knowing it would require several hours. The only other reserve available was the cuirassier brigade of General Kellermann, Duke Valmy. At Marengo in 1800, these horsemen had ridden over three Austrian grenadier battalions and a dragoon regiment, the resulting French victory confirming Bonaparte in power as First Consul. Ney called on Kellermann to repeat that glory: “My dear general, we must save France, we need an extraordinary effort; take your cavalry, throw yourself into the middle of the English army, crush it, trample it underfoot.”

“This order, like those of the emperor, was easier to give than to execute,” wrote Kellermann. It meant sending 800 French cavaliers against nearly 30,000 Allied troops.

“It’s not important, charge with what you have, destroy the English army, trample it underfoot, the salvation of France is in your hands, go!” Ney told him.

Kellermann assembled his brigade and, as he wrote, “without giving them [time] to realize and reflect on the extent of the danger, led them, lost men, into a gulf of fire.” French cavalry usually charged at the trot. “Charge, at full gallop, forward, charge!” he shouted.

Their objective was the open ground to the west of the Brussels road between Gemioncourt and the Bossu Wood. Just to the east of the road, however, the 69th (South Lincolnshire) Regiment of Foot was caught deploying, not into square, but into line. The nearest squadron of cavalry turned on them. “This regiment fired at thirty paces, but without being stopped, the cuirassiers trampled it under foot, destroyed it completely and overthrew everything they found in their path,” wrote a French officer.

In the tangle of hooves, blades, and black powder, the 69th’s regimental color bearer gave his life falling on top of his banner, saving it. But the bearer of the King’s Color was ridden down by a cuirassier who tore the standard from him and bore it off, the ultimate disgrace to a British unit in the field. Several squadrons of French riders actually rode completely through the Allied lines and found themselves clattering about in the crossroads of Quatre Bras itself.

“It had completely succeeded, against all probability,” wrote Kellermann. “A large breach had been made, the enemy army was shaken … the English lines were wavering, uncertain, in the expectation of what was going to happen next. The least support of our reserve cavalry engaged on our right would have completed the success.” But Pire’s cavalry, normally called on for one all-out charge in a battle, had already made two. Their horses were spent. Kellermann’s brigade was all alone. “No longer under the control of its leaders, it was struck by the fire of the enemy, who were recovering from their surprise and fear,” wrote Kellermann.

In just a few minutes, the cuirassiers, crowded into the wedge of the Quatre Bras triangle with enemy muskets and cannons on both sides, lost 300 men. Their general’s own horse was shot out from under him. “Kellermann had the presence of mind to cling to the bits of two of his cuirassier’s horses and so avoid being trampled,” wrote De Vatry. They carried him back to the French lines.

It was the high water mark of II Corps. “If the 1st Corps, or even a single one of its divisions had arrived at this time, the day would have been one of the most glorious for our arms; it needed infantry to secure the prize that the cavalry had taken,” wrote Heymes. But there was none.

As evening came on, Maj. Gen. George Cooke arrived from Nivelles with the British 1st Infantry Division and was immediately ordered to retake the Bossu Wood. “The men gave a cheer, and rushing in drove everything before them to the end of the wood, but the thickness of the underwood soon upset all order, and the French Artillery made the place so hot that it was thought advisable to draw back … more out of range,” wrote Captain Henry Powell of the 1st Foot Guards. “A great many men were killed and wounded by the heads of the trees falling on them as [they were] cut off by cannon shot.”

“The wood of Bossu, taken and retaken three times with huge losses, was taken fourth by the enemy, who never left it,” wrote Lt. Col. Marie Jean Baptiste Lemonnier-Delafosse, Foy’s chief of staff. Among the dead, picked off by a tirailleur, was young Lord Hay, the ensign in the Foot Guards who had so enthralled Lady Georgiana at her mother’s ball. Nearly three-quarters of a century later, as 23rd Baroness de Ros of Helmsley, she still remembered “being quite provoked with poor Lord Hay, a dashing merry youth, full of military ardour, whom I knew very well for his delight at the idea of going into action, and of all the honours he was to gain; and the first news we had on the 16th was that he and the Duke of Brunswick were killed.” By Sunday night, 11 of her mother’s party guests would be dead, including Sir Thomas Picton.

All along the line, fresh Allied troops pushed the exhausted, depleted French back. In the center, they retook Gemioncourt; on the right, Piraumont. As night fell, Ney’s men stood on their original lines before Frasnes, looking out on trampled fields strewn with 4,100 French and 4,800 Allied dead. Winchester remembered he and the survivors of the 92nd Regiment “cooked our provisions in the cuirasses which had belonged to the French Cuirassiers whom we had killed only a few hours before.”

“About nine o’clock, the first corps was sent me by the Emperor, to whom it had been of no service,” Ney testified after the war. “Thus twenty-five or thirty thousand men were, I may say, paralyzed, and were idly paraded during the whole of the battle from the right to the left, and the left to the right, without firing a shot.” When King Louis returned to power, Ney was arrested, tried for treason, stood against a wall near Paris’s Luxembourg Garden, and executed by firing squad.

The entire Hundred Days campaign turned on D’Erlon’s failure to follow either Ney’s or Napoleon’s conflicting orders to join battle at Ligny or Quatre Bras. Ligny was a tactical victory but a strategic defeat as Napoleon vanquished Blucher’s Prussians but failed to knock them out of the war. Quatre Bras was a tactical defeat in that Ney failed to rout the Anglo-Dutch or even take the crossroads, but a strategic victory in that he prevented Wellington from going to the Prussians’ aid.

The two battles set the stage for the climactic clash of the Napoleonic Wars. Wellington himself predicted as much in the map room at the Duchess of Richmond’s house in Brussels on the eve of battle, when he declared, “I have ordered the army to concentrate at Quatre Bras; but we shall not stop [Napoleon] there, and if so I must fight him there,” and pointed on the map to Waterloo.