By Flint Whitlock

Forming the very tip of the Allied spearhead that thrust onto the heavily fortified Omaha beachhead at Normandy was the U.S. 1st Infantry Division’s 16th Infantry Regiment. On D-day, the men proved that, when everything began to go terribly wrong, there was no substitute for the courage of the individual combat soldier.

It seemed almost too much to ask of a mortal man.

In addition to his weapon, ammunition, grenades, rations, and 50 pounds of equipment, each man carried a small flyer signed by the Supreme Commander reiterating the importance of his mission: “You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you. The hopes and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you.”

A pitiful, ragged line of tiny landing craft, each crammed to the gunwales with some 30 to 40 seasick, shivering, soaking-wet soldiers, was heading toward one of the most heavily defended coastlines on earth.

They were riding into hell, their mission to crack Hitler’s vaunted “Atlantic Wall,” reputed to be impenetrable, along the northern coast of France. Nazi Germany had held a tight grip on the Continent ever since France fell in June 1940, and the British Expeditionary Force subsequently was pushed into the English Channel at the French port of Dunkirk. It was June 6, 1944, and it was payback time.

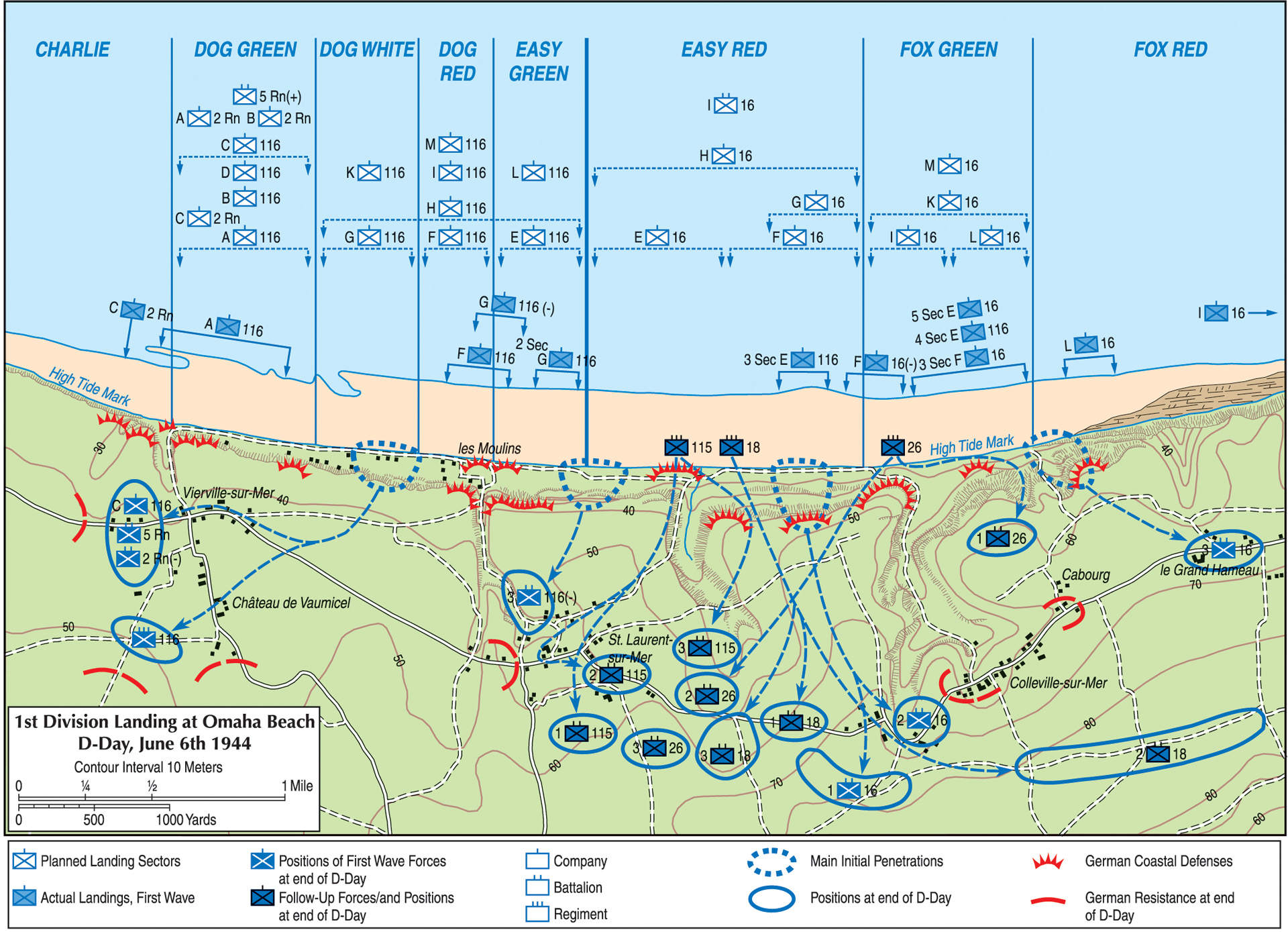

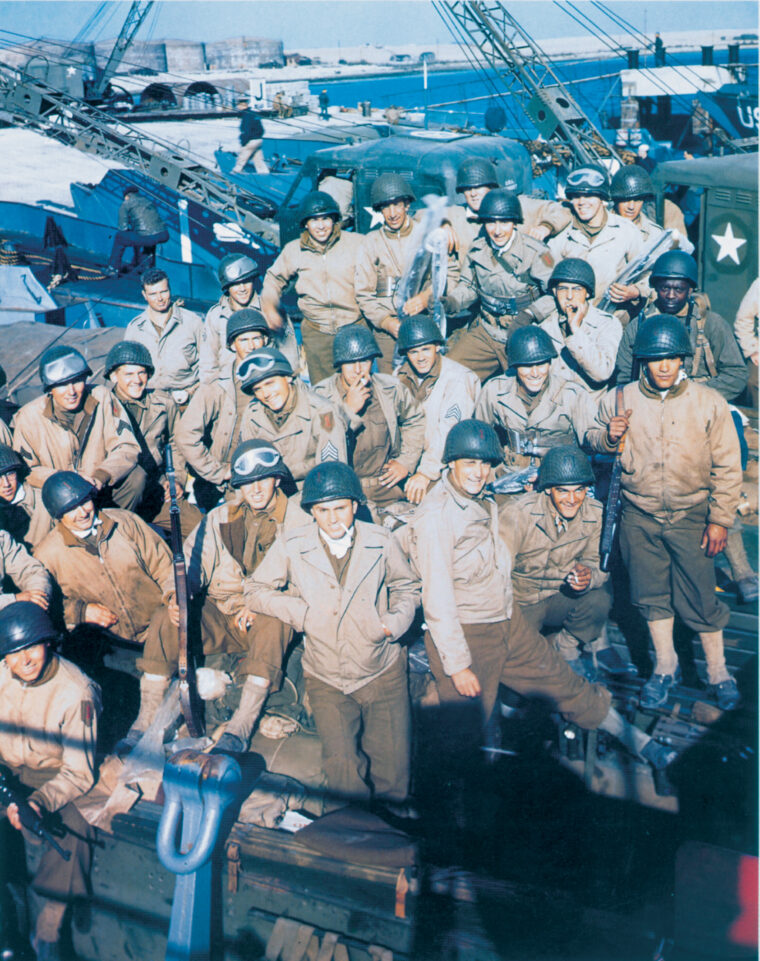

The troops in this first wave, known as Force O, were the 16th Infantry Regimental Combat Team of Maj. Gen. Clarence R. Huebner’s 1st Infantry Division—the Big Red One—which had already seen plenty of combat in North Africa and on Sicily. Attached to the 1st for most of the first day of this operation, known as “Overlord,” was the 116th Infantry Regimental Combat Team of Maj. Gen. Charles Gerhardt’s 29th Infantry Division—a well-trained division that had not yet experienced combat. The 16th, commanded by Colonel George A. Taylor, was scheduled to land on “Easy Red” and “Fox Green” beaches, two sections of a five-mile-long beachhead code-named “Omaha”; the 116th’s assigned sectors, just to the west of the 16th’s, were designated “Dog Green,” “Dog White,” and “Dog Red.”

Four attack transports—the USS Samuel Chase, USS Henrico, USS Dorothea M. Dix, and HMS Empire Anvil—had carried the 1st Infantry Division to a rendezvous point (dubbed “Piccadilly Circus”) in the middle of the English Channel. From there the assault troops transferred into smaller landing craft for the long run into shore. Companies E and F of the 16th Regiment’s 2nd Battalion were scheduled to hit Easy Red Beach a minute after the 32 amphibious Sherman tanks from A Company, 741st Tank Battalion reached shore at H-hour, 0630 hours. At the same moment, on Fox Green, the easternmost sector of Omaha Beach, Companies I and L would swarm ashore. The troops on Easy Red would be reinforced a half-hour later by the arrival of Companies G and H, while Fox Green would be backed up by Companies K and M. About an hour later, Lt. Col. Herbert C. Hicks, Jr.’s2 2nd Battalion would hit the shore, followed by the four companies of Lt. Col. Edmund F. Driscoll’s 1st Battalion and the guns of Lt. Col. George W. Gibbs’ 7th Field Artillery Battalion. Next would come Force B, Colonel George A. Smith, Jr.’s 18th Infantry Regiment and the attached 115th RCT from the 29th. In the early afternoon, Colonel John F.R. Seitz’s 26th Infantry Regiment would come ashore at Easy Red and Fox Green. That was the precisely timed, well-rehearsed plan but, as anyone who has ever been in combat will testify, the battle rarely sticks to the script.

In the predawn darkness aboard HMS Empire Anvil, 21-year-old Private Steve Kellman, a rifleman in L Company, 16th Infantry, felt the crushing weight of the moment: “In the hours before the invasion, while we were below decks, a buddy of mine, Bill Lanaghan—he was as young as I was—said to me, ‘Steve, I’m scared.’ And I said, ‘I’m scared, too.’”

Then, at about 3 or 3:30 that morning, an officer gave the order and Kellman and Lanaghan and the nearly 200 men in L Company began to climb awkwardly over the gunwales of their transport and descend the unsteady “scramble nets,” just as they had done in training so many times before. “The nets were flapping against the side of the vessel, and the little landing craft were bouncing up and down,” said Kellman. “It was critical that you tried to get into the landing craft when it was on the rise because there was a gap—the nets didn’t quite reach and you had to jump down. That was something we hadn’t practiced before. We had practiced going down the nets, but the sea was calm. This was a whole new experience.”

Staff Sergeant Harley A. Reynolds was on USS Samuel Chase with the rest of B Company, 16th Infantry. “When it came time to load into assault boats,” he noted, “we had to climb down cargo nets and drop into the boat. The water was rough from a storm; some men were injured when they dropped in…. We left the Chase for the last time and went in single file to our rendezvous area, following the little light on the stern of the craft ahead of us. The light would disappear, then reappear as we rose and fell with the waves. I thought several times we would crash into the craft ahead as we came up on them and would have to back off. I could see the trail of phosphorus the craft was leaving behind and I thought that the Germans must be able to see it, too, and pinpoint us….”

The heavy-set, bearded Ernest Hemingway, writing an article on the invasion for Collier’s magazine, was in an LCVP with members of a company of the 16th Infantry. He wrote, “As the boat rose to a sea, the green water turned white and came slamming in over the men, the guns, and the cases of explosives. Ahead you could see the coast of France. The gray booms and derrick-forested bulks of the attack transports were behind now, and, over all the sea, boats were crawling forward toward France. As the LCVP rose to the crest of a wave, you saw the line of low, silhouetted cruisers and the two big battlewagons [the battleshipsTexasand Arkansas] lying broadside to the shore. You saw the heat-bright flashes of their guns and the brown smoke that pushed out against the wind and then blew away.”

“We circled in our landing craft for what seemed like an eternity,” recalled Kellman. “The battleships opened up, and the bombers were going over. Every once in a while, I looked over the side, and I could see the smoke and the fire, and I thought to myself, ‘We’re pounding the hell out of them and there isn’t going to be much opposition.’ As we got in closer, we passed some yellow life rafts and I had the impression that they must have been from a plane that went down, or maybe they were from the amphibious tanks that might have sunk; I don’t know. These guys were floating in these rafts and, as we went by, they gave us the ‘thumbs up’ sign. We thought, ‘theydon’t seem very worried—what the hell do wehave to be worried about?’ But, as we got in closer, we could hear the machine-gun bullets hitting the sides of the vessel and the ramp in front.”

“While in training, we were told of all the things that would be done in order,” recalled Harley Reynolds. “But to see it all come together was mind-boggling. The size of it all was stunning. We were trained to keep our heads down until time to unload but, … I felt it better to know what was going on around us. I looked over and ahead many times and what I saw was terrifying.”

What Reynolds saw was a heavily fortified, enemy-held beachhead that had barely been touched by Allied bombs and shells. The tremendous air and naval bombardment (“drenching fire,” the Allied planners had called it) that the troops had been assured of in their briefings and rehearsals would blow gaps in the minefields and beach obstacles, turn the pillboxes and casemates into dust, and annihilate the defenders who were thought to be only low-grade troops unfit for duty on more active fronts had not materialized.

The bombers, flying above low overcast, had released their bombs too far inland, causing casualties only among Norman cows. The Navy, fearful of hitting the disembarking infantry, also overshot the target. Underwater demolition experts had gone in early to blow gaps in the obstacles and mark safe paths to the beach, but most of them were either dead, wounded, or had lost all their specialized equipment in the rough surf. All but five of the 32 amphibious Sherman tanks, which were supposed to have reached Easy Red and Fox Green before the infantry, had sunk, carrying their crewmen to their deaths. Even specially fitted landing craft carrying an arsenal of rockets close to shore missed everything. There was not so much as a single bomb crater on the beach in which to hide, and the German gunners were all alert and zeroed in on the narrow strip of beach. The largest and most carefully planned and rehearsed invasion in the history of warfare was on the verge of disaster—and the troops had not even reached land.

Even if a hot reception awaited them, the men in the small landing craft known as LCVPs or Higgins boats could not wait to reach the shore. Most of the men had been unable to sleep all night, June 5-6, 1944, thanks to preinvasion jitters. The troops in the first wave had eaten breakfast shortly after midnight, then were loaded from their transports in the middle of the English Channel into the pitching craft. The last vestiges of a storm that had delayed the invasion by a day were still passing through the assembly area, and the sea was extremely rough. The run-in to shore was a long one; it would take most of the boats three to four hours. Those three to four hours were unremitting misery to the troops on whom the success of the greatest amphibious assault ever mounted depended. Not only were the little boats rocked up and down on the big waves, but they were also pitched side to side. It was, one of the men commented, “like being trapped on a never-ending roller-coaster ride.” Another described it as “like being inside a washing machine.”

The heavily laden men tried to maintain their balance on the slick decks, only to be thrown into the men in front, back, or on either side of them. Great waves came out of the predawn darkness and smashed into the flat bows of the boats, sending cascades of icy sea water onto the helpless soldiers, who were now wading in their own vomit as well as that of their comrades. “We had been issued a puke bag for seasickness but, as it turned out, one wasn’t enough,” remembered Pfc. Roger Brugger, K Company, 16th Infantry. “After the LCVPs were lowered, we kept going around in circles, rendezvousing. By this time, everyone in the boat had used their bag and were throwing up on the deck of the boat.”

For many of the men in the rocking, bouncing, jolting boats, seasickness overrode their fear of death or injury. Signal Corps cinematographer Walter Halloran recalled, “I don’t think that fear was a recognizable element. We were so seasick, our only thought was, ‘We’ve got to get off this boat.’”

“It was literally a choice between the devil and the deep blue sea,” said one 1st Engineer Combat Battalion officer. “We all agreed we’d rather face the devil.”

The Germans had done an outstanding job of fortifying the northern coast of France from enemy attack. From Cherbourg to Calais, the entire coastline was a gigantic steel-and-concrete nightmare for the attackers. Virtually every foot of ground was covered by direct- and indirect-fire weapons—rifles, machine guns, mortars, 105mm guns, and the dreaded 88s. Likely invasion beaches were studded with underwater and beach obstacles designed to rip the bellies out of landing craft or blow them to bits with mines.

Mines, too, were profligate under the beach sands and backed by thickets of barbed wire. Beyond the wire were concrete foxholes, elaborate trench systems, and concrete bunkers and gun emplacements sited to scythe down any invaders with enfilading crossfire. And all that was before the tall bluffs that rose above the beachhead and had their own interconnected series of defensive positions and strongpoints. The entire enterprise was under one of Germany’s most able commanders, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, who, above almost everyone else in the German High Command, was a genius at waging successful war even when outnumbered.

On January 15, 1944, Rommel had become commander of Army Group B, whose area of responsibility included the coast of northern France. In this role, he was also commander of the 7th and 15th Armies, but with severe limitations on his operational capabilities. Rommel had been working the troops to exhaustion for five months to improve on Hitler’s Atlantic Wall—including the installation of over four million mines between Cherbourg and Calais—for he sensed the great invasion was imminent. Despite the improvements, Rommel feared it would not be enough.

While the physical aspect of the defense was impressive, the manpower was lacking. Many of Germany’s finest soldiers were no longer available for the defense of the Reich; they had been killed or maimed during nearly five years of fighting at such places as El Alamein, Sicily, Monte Cassino, Crete, Leningrad, Stalingrad, and a thousand other battlefields. With the Soviets pressing the Germans hard on the Eastern Front, what was left to defend Normandy were a few understrength, over-age, static regiments and battalions with only bicycles and horses for transport. Unknown to most of the Allied planners, a reconstituted motorized infantry division, the 352nd, had been brought up to reinforce the thinly spread 716th Coastal Defense Division in the Omaha Beach area. Marginally better manned and equipped than the 716th, the 352nd, recently mauled on the Eastern Front, was not considered a first-class fighting force; still it gave the Germans 10,000 more men at Normandy than the Allies thought were there.

Only the panzer divisions could be considered a real threat to the invasion, and these were kept well back from the coast by 67-year-old Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, Commander-in-Chief, West, to prevent their being destroyed by Allied air superiority. Worse, Rommel did not have operational control of these panzer units; they could only be released for action upon personal authorization of Adolf Hitler, and Hitler was convinced the real invasion would come at Calais, not at Normandy. To compound the problems of the German units in Normandy, many of their commanders were absent from their posts on the crucial night of June 5-6, away at a map exercise in Rennes, 90 miles to the southwest or, in Rommel’s case, off in Germany to plead directly with Hitler for more authority to conduct the defense of the coast in the manner he saw fit, and to visit his wife on her 50th birthday.

The first wave of landing craft—transporting the 2nd Battalion of the 16th Infantry Regiment—somehow managed to slip through most of the falling shells and sea obstacles to deposit the men close to shore, but the initial landing at Easy Red Beach was anything but easy. Because of a strong west-to-east current, nearly every boat was landed a half-mile or more east of where it was supposed to be. Men who had been carefully trained for months to recognize landmarks on shore now had no idea where they were. Officers and NCOs leading their men out of the boats were among the first hit; units were scrambled, cut off, lost. Leaderless, and being subjected to a tremendous pounding, the seasick, shaken survivors waded ashore and headed for a thin strip of small, rounded rocks, known as “shingle,” at the high-tide mark and huddled together, waiting to die.

On Fox Green Beach, things were as bad as on Easy Red. Five boat sections of F Company, 16th Infantry were scattered across a thousand yards of sand. Two sections of the company did manage to land close together in front of enemy positions, but were decimated by machine guns and mortars as they departed from their LCVPs. Six officers and half of the company became casualties in a matter of minutes. The remaining boat section of E Company, 16th Infantry reached the shore where water and sand were spouting in an endless flurry of artillery and mortar explosions.

Four boat sections of E Company, 116th Infantry also drifted into the area and experienced the same, terrible greeting. Men discarded their equipment in the water and scrambled for the safety of the shore, but it was no better than the sea. Minefields and machine guns were in front of the invaders, and a steadily encroaching tide was behind them. All around was death, destruction, carnage, and chaos. Among those who had somehow made it to the beach, there was a very real sense that no one was going to come out of this debacle alive.

Captain Ed Wozenski, commanding E Company, 16th Infantry, one of the first elements to land on Omaha Beach, recalled his unit’s experiences: “MG [machine-gun] fire was rattling against the ramp as the boat grounded. For some reason, the ramp was not latched during any part of our trip, but the ramp would not go down. Four or five men battered at the ramp until it fell, and the men with it. The boats were hurriedly emptied—the men jumping into water shoulder deep, under intense MG and AT [antitank] fire. No sooner was the last man out than the boat received two direct hits from an AT gun, and was believed to have burned and blown up.

“Now all the men in the company could be seen wading ashore into the field of intense fire from the MGs, rifles, AT guns, and mortars. Due to the heavy sea, the strong cross current, and the loads that the men were carrying, no one could run. It was just a slow, methodical march with absolutely no cover up to the enemy’s commanding positions. Many fell left and right, and the water reddened with their blood. A few men hit underwater mines of some sort and were blown out of the sea. The others staggered onto the obstacle-covered, yet completely exposed, beach. Here men, in sheer exhaustion, hit the beach only to rise and move forward through a tide runlet that threatened to sweep them off their feet. Men were falling on all sides, but the survivors still moved forward and eventually worked up to a pile of shale at the high-water mark. This offered momentary protection against the murderous fire of the close-in enemy guns, but his mortars were still raising hell.”

Captain Joe Dawson’s G Company, 16th Infantry approached Easy Red at about 0700. “When we landed, it was total chaos, because the first wave from … E Company and F Company had been virtually decimated. That was due to circumstances over which they had no control. In the first place, they were badly disorganized when they landed, whereas I was privileged to land intact with all of my men and my LCVP in the very point that I was supposed to land in…. I was the first man off my boat, or off of allour boats, followed by my communications sergeant and my company clerk. Unfortunately, my boat was hit with a direct hit, so the rest of my headquarters company was wiped out, as well as the [fire] control officer from the Navy, which was our communication, to give us support fire that was supposed to [neutralize] the village of Colleville, which was the objective that I was given….”

The situation was no better on the 116th Infantry’s portion of Omaha Beach. In fact, it was, if anything, even worse. On Dog Green Beach, A Company of the 116th Infantry was being systematically slaughtered even before it reached shore. One LCA took four direct hits and blew apart. Men coming off LCVPs were torn to bits; others, leaping over the gunwales of their landing craft, were pulled under water by the weight of their packs and equipment, and drowned. Every officer in A Company, and most of the NCOs, became casualties. A small, 64-man company of Rangers, following A Company, was similarly decimated. They lost half their men; A Company lost two-thirds. And they had yet to fire a shot.

Farther west, Rangers (also attached to the 1st Division) were attempting to climb the sheer cliffs to get at the casemated battery of 155mm guns at Pointe du Hoc and were taking heavy casualties in the process. The Rangers would soon discover that the guns had been removed farther inland. However, they accomplished their mission and destroyed the guns.

Some of the soldiers could not handle the horror of the beachhead. One young 16th RCT soldier barely survived a near-miss from a German shell. “When that shell burst,” he recalled, “I guess I panicked. I started crying. There was a ship to our right that had [run aground], and my buddies got me behind that ship, where I cried for what seemed like hours. I cried until tears would no longer come. Suddenly, I felt something. I can’t explain it, but a feeling went through my body and I stopped crying and came to my senses.” The soldier picked up his rifle and got back in the war.

At Easy Red and Fox Green, the leading companies of the 16th RCT were trapped on the beach. The only way to break out of the trap was for one man, or several, to risk their lives by crawling forward, armed with little more than wire cutters or Bangalore torpedoes—20-pound tubes packed with explosives—and expose themselves to enemy fire while they attempted to cut through the wire. Several brave men tried it; all were killed. Despite witnessing the suicidal nature of the mission, another soldier, Sergeant Phillip Streczyk of Wozenski’s E Company, attempted the impossible. With practically every German weapon within range zeroing in on him, Streczyk made a mad dash for the wire through a hail of bullets, snipped it, then waved for the rest of the troops to follow him.

Although E Company had taken a tremendous pounding, one of its surviving platoon commanders, Lieutenant John N. Spaulding, a Kentuckian, gathered what few men he could find. Faced with furious rifle, machine-gun, mortar, and artillery fire, and confronted by profuse minefields, Spaulding set off through the slim gap made by Streczyk in an attempt to crack the enemy positions to the east of a heavily defended exit off the beach designated “E-1.” It was a pitiful, foolhardy attempt, a handful of sick, soaked, and scared soldiers throwing themselves at one of the most heavily defended places on earth. There was no way it could succeed. But somehow, incredibly, it did.

With Dawson’s Company G providing covering fire, Spaulding and his men crept forward, leaving a path of death and destruction in their wake. As the regimental report said, “Of the 183 men [in E Company] that landed, 100 were dead, wounded, or missing.” But the survivors, led by Spaulding, “reduced the strongpoint at [map coordinates] 678897, consisting of an anti-aircraft gun, four concrete shelters, two pillboxes, five machine guns, pillbox by pillbox to wipe out the strongpoint covering the east side of Exit E-1. Extremely stubborn resistance was encountered in this strongpoint with its maze of underground shelter trenches and dugouts. A close exchange of hand grenades and small-arms fire ensued until the 1st Platoon cornered approximately twenty Germans and an officer who, overpowered, surrendered….”

Now it was Dawson’s turn to move out. “I felt the obligation to lead my men off, because the only way they were going to get off was to follow me; they wouldn’t get off by themselves … We dropped over [the shingle] and got into this minefield. There was a body of a boy who had found the minefield and unfortunately also found the mine and destroyed himself, but he pointed the way for us to go across him, which we did. Sergeant Cleff and myself, and Pfc. Baldridge, another man in my company, started up the hill…. There was a path and it seemed to generally go in the right direction toward the crest of the hill, so I started up that way. About halfway there, I encountered Lieutenant Spaulding with a remnant of his platoon. I think he had two squads and a person in a third squad, and they were the only survivors that I knew of at that time in E Company. He joined us at that time and became part of us; my men were still back on the beach.

“I told Baldridge to go back and bring the men up. I said, ‘They’ve got to get off the beach. Tell them to come up here with me.’ Well, they started up, but I had gone on ahead. Just before you reach the crest of the ridge, it becomes almost vertical for about a 10-foot drop. There was a log there and I got behind the log to see if I could see my men coming up… . I could see a single file beginning to develop off of the beach coming on up when I heard a great deal of noise just above me and, sure enough, there was a machine-gun nest up there and they were giving us a lot of trouble. I was able to get within a few yards of them…. I lobbed a couple of grenades in there and silenced them and that opened the beach up. It was a miracle. It doesn’t mean anything on my part. It was just one of those wacky things that happen, that I was on the right spot….”

While the boats in the initial waves drifted several thousand yards off course, the boats carrying I and L Companies, which were supposed to land on Fox Green at the same time E and F Companies were hitting Easy Red, were pulled more than a mile off course, almost landing on Gold Beach at Arromanches, in the British 50th Infantry Division sector. By the time the error could be corrected, Captain John R. Armellino’s L Company had lost a boat that capsized two miles off shore and was more than a half-hour late; it would take over an hour more for Captain Kimball Richmond’s I Company to reach land.

Originally scheduled to land in front of the E-3 draw, the L Company boats beached beyond the extreme eastern boundary of Fox Green, near the shelter of low cliffs that came down nearly to the water’s edge. Organizing his company in the relative safety of the cliffs, Captain Armellino saw that his unit, although it had already lost nearly half its strength, was basically intact—the only one of eight companies in this initial wave able to operate as a unit.

One of those in Armellino’s company was Private Steve Kellman: “We were trained, when you hit the beach, to never run in a straight line—you were supposed to zig-zag. When the ramp went down, some of the fellows just went straight as an arrow, and a lot of them were cut down that way. The coxswain on our boat got us right up on the beach—I don’t think the water was as high as our knees. We had a tremendous advantage—we didn’t have to wade; we could run. We just ran like hell to get up against that little sea wall. Once we got there, we were exhausted. Some of the guys in the boats behind us, where the coxswains didn’t get them close enough, they had to hide behind those obstacles that were in the water, thinking that they were going to provide them with some cover, but that was deadly.”

Armellino decided to push inland, toward the village of Le Grand Hameau. The only way up to the heights was a draw labeled on maps as “F-1,” which was guarded by not one but two strongpoints, numbers 60 and 61.

But Kellman would not make it up the draw. “On the beach, it was like all hell had broken loose,” said Kellman. “There was noise and smoke and dead bodies all over the place. We found we were not on the right beach…. As we were working our way to the right beach, an artillery or mortar round must have landed 15 feet away and the fellow that was in front of me and I both got flipped over backwards by the concussion. Then I started to crawl, and I got against the sea wall. I knew we had to move, and I used my rifle like a crutch to stand up. I got to a standing position and then fell down. I didn’t know what was wrong—I didn’t feel any pain; it was like a numbness. I tried standing again, and I fell down again. I pulled up my trouser leg, and I could see blood. I was so scared. I took off my leggings and sprinkled sulfa powder on the wound and wrapped a bandage around it.

“As the succeeding waves came in, I gave my rifle to one fellow and gave my grenades to another, so I was without anything. Then our company executive officer, Lieutenant [Robert] Cutler, came along and said, ‘Come on—we’re moving out.’ I said, ‘I can’t.’ He looked at me and said, ‘Kellman, I didn’t think I was going to have any trouble with you.’ I said, ‘I can’t walk, sir.’ He said, ‘What’s the matter?’ I showed him my leg, and he said, ‘Oh, okay. I’ll have an aid man come by.’

“The guy who had been flipped over in front of me by the shell had also been hit in the leg, and we laid there and talked while we waited for the aid man. The shells kept coming in. After the concussion of one of them, I kind of sat up and asked him, ‘How’re you doing?’ But he had been hit again and was dead.”

Now it was the turn of Captain Anthony Prucnal’s K Company to arrive at Fox Green Beach. Originally intended to be the 2nd Battalion’s reserve company at Fox Green, they were thrust into an assault role after I Company had drifted too far east. A member of the company, Pfc. Roger Brugger, recalled, “As we approached the beach, the shells were dropping in the water and machine-gun bullets were whizzing over our heads. Sergeant Robey [the squad leader] told the coxswain to run our boat right up on the beach and not let us off in four or five feet of water. He did, and we got off on dry land. I remember thinking as I ran from the boat with the bullets tearing up the sand on either side of me, ‘This is like a war movie.’ After we got to the shale wall, I looked back at the boat we had just left when an 88mm artillery shell hit it in the engine compartment and it blew up. I watched another boat come in and, as the guys came running to the wall, one guy got a direct hit with a mortar shell, and all I could see of him were three hunks of his body flying through the air. We were all sick and scared from the pounding and the ride. When we tried to throw up, there wasn’t anything left. The tide was coming in and the beach was getting smaller.”

K Company’s six boats came under heavy enemy fire, and two were blown up by mines. The officer corps was decimated in minutes. As Prucnal and his XO, First Lt. Frederick L. Brandt, were attempting to organize the remnants of the company, a shell screamed in and mortally wounded Brandt. Coming to his aid, Prucnal was killed by another shell. A platoon commander, Lieutenant James L. Robinson, attempted to rally the company only to fall dead at the hands of a sniper. Another lieutenant, Alexander H. Zbylut, was wounded while struggling ashore. Taking command of the rapidly dwindling unit, Lieutenant Leo A. Stumbaugh organized a patrol of what was left of the first and second assault sections, dashed through a blaze of enemy fire, and forced Germans holding a defensive position to withdraw. The right flank of the German line holding Omaha Beach was slowly, almost imperceptibly, beginning to crumble.

First Lieutenant Karl E. Wolf, a West Point graduate from Wethersfield, Connecticut, assigned to Headquarters Company, 3rd Battalion, 16th Infantry, recalled, “For a while, we had to dig in or lay on the beach because of enemy fire. The beach was fairly steep for about 20 to 30 yards, and at the top there was a little berm that afforded us a little protection.” Although somewhat sheltered, Wolf found that he had crawled into a nightmare. “While laying there, I noticed the soldier near me was lying on his back, and his whole leg was split open to the bone. He was in shock, but there was nothing I could do except keep pulling him up as the water rose. Nearby was half a body, the lower half having been blown away.”

More units piled up on shore. Radioman Al Alvarez, with the 7th Field Artillery Battalion supporting the 16th RCT, recalled, “After what seemed like hours, we finally left the comparative safety of these beach obstacles. Then, crawling and dragging, we emerged and hid behind a mounded row of pebbles, sort of a berm lined with hundreds of soldiers. Eddie King went back into the surf to pull in wounded, drowning soldiers, and then pointed to his head where blood trickled down his face. There in the center of his helmet was a bullet hole where a round had gone through his helmet, dead center! I had the task of sticking my hand in his helmet and feeling mush, but it was only his hair soaked in blood. It turned out to be only a crease. But then a medic was called over and sat down with his back to the enemy and bandaged Eddie, but was struck in the back. Both of us tried bandaging him and called other medics, but he died.”

It seemed that every German gun within range of Omaha Beach was firing as fast and as furiously as it could at the incoming landing craft, at the men struggling to get ashore, and at those who had already found a temporary respite on the round rocks of the shingle behind the low sea wall. Boats were torn apart by direct hits; those men too badly wounded to extricate themselves from the surf were drowned by the rising tide; and those taking cover behind obstacles were slaughtered by the unceasing storm of artillery shells and mortar bombs.

The cries of the wounded rose above the awful din, and men who tried to assist the dying and injured were themselves killed or wounded. Some of the best-trained soldiers in the world became casualties before they could even get a glimpse of the enemy. As the German fire reached a thundering crescendo, there seemed to be no possible hope for the 1st Infantry Division to establish a beachhead, let alone move inland and take its objectives. The 16th Infantry Regiment, like the 116th to its right, had been halted dead in its tracks, and annihilation seemed to be the inevitable outcome.

War correspondent Don Whitehead noted, “The invasion on Omaha Beach was a dead standstill! The battle was being fought at the water’s edge! I lay on the beach wanting to burrow into the gravel. And I thought: ‘This time we have failed! God, we have failed! Nothing has moved from this beach and soon, over that bluff, will come the Germans. They’ll come swarming down on us….’”

But the Germans did not come swarming down. The 16th’s firebrand commander, Colonel George A. Taylor, was now ashore and began inspiring and rallying the troops. Seeing men huddled where they could find the barest shred of safety, Taylor was filled with rage, both at the enemy and at his own cowering men. Technician John E. Bistrica, a member of C Company, 16th Infantry, clearly remembered one of the most heralded moments of World War II, perhaps the single moment that turned the tide for the American assault on Omaha Beach: “Colonel Taylor came in after the assault waves. He was roaming up and down along the beach. He yelled, ‘There are two kinds of people who are staying on this beach—those who are dead and those who are going to die! Now let’s get the hell out of here!’

“I says, ‘Well, somebody finally got this thing organized. I guess we’re going to move out now.’ So we started up the draw.”

From their places of safety, men who had been paralyzed with fear slowly began to emerge. Many of them, to be sure, were killed or wounded the moment they showed themselves to the enemy. But a handful of courageous captains and lieutenants and sergeants and corporals turned to the frightened men next to them and issued a brief, no-nonsense order: “Follow me.” And the men followed.

Don Whitehead wrote, “There were many heroes on Omaha Beach that bloody day, but none of greater stature than [Assistant 1st Division Commander Willard G.] Wyman and Taylor. They formed the core of the steadying influence that slowly began to weld the 1st Division’s broken spearhead into a fighting force under the muzzles of enemy guns. It’s one thing to organize an attack while safely behind the lines—and quite another to do the same job under the direct fire of the enemy.”

John B. Ellery, a platoon sergeant in the 16th RCT, witnessed firsthand several examples of leadership. “I [saw] a captain and two lieutenants who demonstrated courage beyond belief as they struggled to bring order to the chaos around them; they managed to get some of the men organized and moving forward up the hill. One of the lieutenants was hit and seemed to have a broken arm … but he led a small group of six or seven to the top. It looked as though he got hit again on the way. Another lieutenant carried one of his wounded men about 30 meters before getting hit himself. When you talk about combat leadership at Normandy, I don’t see how the credit can go to anyone other than the company-grade officers and senior NCOs who led the way. We sometimes forget that you can manufacture weapons and you can purchase ammunition, but you can’t buy valor, and you can’t pull heroes off an assembly line.”

While a seemingly unending deluge of bullets and red-hot, jagged shell fragments continued to rain down on the men lying on the beach, Sergeant Harley Reynolds, in B Company’s sector, looked up. “I could see a narrow pond ahead with marsh grass. Between us and the pond was the wire strung on the roadbed and beyond that a three-strand wire fence with a trip wire only on the front of it.”

A soldier with a bangalore torpedo managed to slip it under the barbed wire and blew a gap, then was shot and killed. Without hesitating, Reynolds and his men flew through the break in the wire and into a flooded antitank ditch beyond. “I was the first across the pond and, as I paused to take off the life preserver, I looked back to see how the men were doing. I heard my name called and looked to see Dale Heap, about halfway across the pond. Dale was gunner on one of the machine guns and the platoon comedian. He had been shot through his upper arm—a good flesh wound. He was holding his one arm above his head and pointing his gun tripod at it, saying, ‘See, I didn’t drop the tripod.’ Always the comedian, he was actually laughing. He kept yelling, ‘Stateside! Stateside!’ He handed the tripod to his assistant gunner, the first ammo carrier took the gun, and we had a battlefield promotion right there in the middle of the pond. Dale waved goodbye and headed back to the beach. He made it stateside, and that was the last we heard from him.”

At 0830 hours, a Navy beachmaster managed to signal the fleet that no more landing craft were to come ashore—there simply was no room for them, and no room for the men and vehicles they carried. At this time, there were some 50 LCTs and LCIs circling offshore, looking in vain for some place to deposit their cargo. Their skippers could see landing craft from the previous waves foundering, sinking, burning, or hung up on obstacles, with the sea around them being ripped by tremendous explosions. There appeared to be no safe passages.

The situation would remain almost unchanged for two more hours. Seeing the infantry being subjected to continual pounding, the Navy determined that its firepower, which had been less than effective thus far, must be brought to bear at close range against enemy targets, even if it meant risking the ships and their crews. A flotilla of destroyers moved close to shore and began hammering German positions.

Almost imperceptibly, and despite the best efforts of the German gunners, the thickets of barbed wire, and the innumerable minefields, the surviving invaders gradually began to chip small fissures in Hitler’s Atlantic Wall. Pillboxes and trenches were being swept away by the hot breath of the Navy’s guns. The pinned-down American infantrymen were pinned down no longer. As German fire slackened, through the barbed wire and minefields the Yanks slithered, like an inexorable, olive-drab swarm of angry, heavily armed insects, bent on overcoming all obstacles in their path.

The Germans manning the fortifications, their ears and noses bleeding from the concussions of the direct hits and near misses, and their throats choking from concrete dust and cordite, began scrambling out the steel rear doors in hopes of making it to the top of the bluffs and safety, only to be cut down in the midst of their escape attempts. The tide of battle had turned.

June 6, 1944, especially at Omaha Beach, had been a bloody affair—worse than even the most pessimistic soldiers had feared. The human cost of the operation was very high, although the exact number of casualties may never be known. Some 291 landing craft had been lost on D-day, and numerous destroyers, LCTs, LCIs, and amphibious DUKWs had been sunk.

In the 1st Infantry Division, it is estimated that 18 officers and 168 enlisted men had been killed or died of wounds on D-day; 7 officers and 351 men were missing; and 45 officers and 575 men were wounded in action. Elements of the 29th Infantry Division, attached to the 1st, had also suffered grievously, with 328 men killed or dead of wounds, 281 wounded, and 134 listed as missing in action.

Yet, many thousands more had stormed ashore over the bodies of their fallen comrades, braved the intense fire, crawled through the minefields, lobbed grenades into pillbox embrasures, battled with defenders in their trenches, and reached the top of the bluffs by early afternoon. Those who were killed on Normandy’s chilly shore had not died in vain; Hitler’s vaunted Atlantic Wall, a defensive fortification that had taken Germany years and many billions of Reichsmarks to construct, had been cracked wide open by the invaders in the span of a morning.

The first day of the Battle of Normandy had gone to the Allies, due in large measure to the selfless courage of the men of the 1st Infantry Division and the attached 29th. Nearly a year of hard fighting still lay ahead, and many of the men who survived D-day would not live to celebrate the victory. But the Allies were back on the Continent to stay, and there would be no turning back now.