By Zita Ballinger Fletcher

The name Field Marshal Erwin Rommel—associated with tank warfare in Europe and North Africa during World War II—might conjure up mental images of the famous “Desert Fox” riding in a panzer, reviewing maps, or commanding battles. What one might not imagine is that in the midst of commanding frontline troops, Erwin Rommel toted a camera and wielded a lens with artistic imagination and precision amid gunshots and shell bursts. In fact, he created thousands of striking war photos prior to his death in 1944.

Rommel’s photography shows that the field marshal had an eye for irony, great attention to detail, an attraction to flowers, and a daring streak—he often tempted mortal danger to snap dramatic action pictures during battles. He was also keenly interested in his fellow soldiers. An overwhelming majority of Rommel’s photographs document simple and poignant moments in the everyday lives of his men—as well as their final resting places. Rommel went out of his way to photograph the makeshift battlefield graves of soldiers who fought alongside him and under his command. Rommel’s war photos included images he wished to publish as documentation of his campaigns as well as many private mementos. He labeled many of his pictures with handwritten captions.

Rommel took the majority of his wartime pictures during his campaigns between 1940 and 1942, although he took some during his command of Army Group B and the fortifying of the Normandy coastline in 1944. His life was brought to an abrupt end several months after the successful Allied invasion of Europe on D-Day. It is interesting to note that the photographs taken during the early stages of the war number in the thousands. However, as the tide turned against the Germans, Rommel became disillusioned and focused solely on his command duties as well as on his own growing discontent with Nazi leadership. As a result, the photographs he took during the last year of his life were strictly for military purposes—lacking the élan and spontaneity that characterizes his earlier work.

Rommel used a Leica camera for much of his photography. Some of his early war photos, particularly from his 1940 campaign in Belgium and France, were taken using a different camera.

Since photography was a passion for Rommel for many years preceding the war, he owned many lenses, camera attachments, and other photography equipment. According to his son Manfred, Rommel’s camera equipment was stolen by American GIs, who looted their rural home in 1945. In addition, Rommel’s wartime photography collection was carted off by two American counterintelligence officers, who discovered it in a trunk during a search of the house. They provided the Rommel family with a receipt for the confiscated material. However, the family later was unable to locate the officers or discover the whereabouts of the pictures.

I discovered the obscure photograph collection in the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Washington, D.C., while I was a teenager in high school doing research for a book. Afterward, I spent several years doing research on Rommel and his photos and embarked on a mission to digitally restore the pictures, which were badly damaged. My project continued throughout my college years. During that time, I wrote a letter to Manfred Rommel to inform him about the location of his father’s photo collection at NARA, in case he was unaware. I sent Manfred copies of some of his father’s photographs along with my letter. Manfred wrote back to me, confirming that it indeed was his father’s photography. He also provided me with information about a museum in Germany where I could donate the photos to be kept with the rest of his father’s estate. At the time of his letter, Manfred was suffering from a long illness and passed away in 2013.

My senior honor’s thesis at the University of South Florida focused on my restoration work with the Rommel photos. The work evolved into a book series called Erwin Rommel: Photographer, the first volume of which was published in 2015.

I moved to Germany in December 2016 after taking a job there as a foreign correspondent for a wire service. The following spring, I contacted the museum Manfred had written to me about, the Haus der Geschichte in Baden Württemberg, and arranged to meet with the museum’s staff to show them the photographs I had digitally restored. The archivists recognized immediately that the photos were taken by Rommel. They informed me that the photos I had brought matched reels of negatives that had been inside Rommel’s home, and were then in their possession. However, their reels were few and incomplete. The photos I had provided the missing pieces.

The archivists were completely astonished to behold the images. Rommel’s photographs had not been seen in Germany since before the end of the war, when a pair of American Army officers hauled away a large trunk across the gravel driveway of his home in Herrlingen in 1945. It had been 72 years since the pictures had vanished without a trace. There was an atmosphere of shock and anticipation in the museum when these images resurfaced.

The archivists were particularly fascinated by the photos Rommel took of North Africa. They informed me that photos from behind German lines in North Africa are extremely rare in Germany. They were also excited to see Rommel’s color pictures. They did not even know that Rommel’s color photography existed.

I donated electronic copies of Rommel’s photography that I had digitally restored to the Haus der Geschichte Museum photo archive in 2017, in addition to my research notes in the hope that the photos would be of educational use to any Germans who wished to view them. The images were reunited with those that had been left behind at Rommel’s home and were to be kept at the museum with his other remaining personal belongings.

Studying Rommel’s photography, I identified patterns in his work and several key themes in which he showed special visual interest. Some of these reflect his interests as a professional soldier and a general, such as those depicting troop maneuvers, fortifications, and action shots during battles. Other images reveal Rommel’s personal quirks. No matter what the subject matter, all of the images contain distinct idiosyncrasies that appear like fingerprints in all of Rommel’s images.

As a photographer, the field marshal was quite meticulous. Although he snapped most of his photographs spontaneously while leading his lightning-fast military advances, he somehow managed to create quick images with measured, mathematical precision. For example, Rommel’s focal objects always tend to be perfectly centered within the frame. Lines also always appear measured and balanced in shots in geometrically even compositions. For many photographers, such precision is difficult to achieve without practice and tends to be difficult to pull off when taking snaps on the run. Rommel, however, was both fast and exacting. Precision was a reflex for him when he composed his shots.

Rommel had an eye for drama and was drawn to overpowering shadows, stark light, and dominating lines. He often took larger-than-life images of machines, tanks, and vehicles. He also captured dramatic images of nature, knife-like sand dunes, steep craggy cliffs, and massive sandstorms. He liked to photograph people in the midst of activity; rarely are his human subjects idle or completely at leisure.

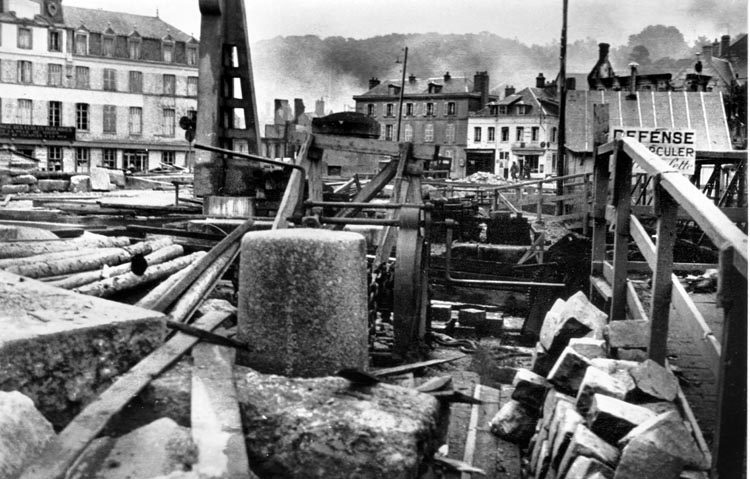

One of the most interesting aspects of Rommel’s photography was his attention to contrast and irony. When exploring areas around him, particularly in the aftermath of a battle, Rommel noticed things in his environment that created ironic contrasts or that were amiss. He would snap a single picture of these haunting or bewildering scenes as if making a note. Here is a French soldier retreating sullenly before a charging statue of Napoleon in Cherbourg. A German soldier in North Africa sits alertly with binoculars on a broken-down vehicle. A classical statue poses prettily at the end of a street beside a row of parked military vehicles. Understated ironies such as these frequently appeared in Rommel’s lens.

Perhaps Rommel’s most haunting composition style—one that seems to have been his favorite—was to capture lone human figures against vast or overpowering backdrops. In another kind of contrast, Rommel liked to capture images of small human figures, either isolated or diminutive in the frame, against overwhelming backgrounds: for example, lone German soldiers walking across wide, open spaces being totally dwarfed by nature or advancing tanks. These pictures portray the individual as a tiny speck in a world filled with motion, peril, or emptiness. The images often create a sense of loneliness and void. They give the viewer some kind of insight into Rommel’s psyche. Why, out of the many diverse approaches to photo composition available to him, did this methodical photographer choose to cast human figures in such a desolate, remote light? The answer to that question is something for observers of Rommel’s photos to theorize.

With regard to the human subjects of his photos, the field marshal tended to focus mostly on soldiers. He showed no discrimination with regard to soldiers that he chose to photograph—they could be German or Italian, English or Indian, Axis or Allied. He clearly enjoyed mingling with enlisted men because he took many pictures of them on and off the battlefield as they were engaging in a wide variety of activities. He also occasionally photographed POWs—among them a turban-wearing Sikh and a kilt-wearing Scot—out of apparent curiosity. The soldiers are usually working, pausing a moment for rest, or in the midst of traveling. There are no photographs of men lounging, playing card games, or engaging in soldierly pranks; it appears Rommel had little interest in leisurely pastimes. There are a few exceptions to this rule. He did snap a few pictures of a soldier playing guitar, and he also took some unassuming shots at social gatherings he attended. It is evident from his photography, however, that when it came to personal interactions, the general was predominantly concerned with his work.

Rommel was emotionally attached to his soldiers, which is evidenced not only by his writings, but also by his numerous private photographs of soldiers’ graves that he took in France and North Africa. Most of these are unmarked and were clearly intended as personal mementos. Rommel kept other burial photos as memorials or tributes. He wrote captions on some images, describing the bravery of particular soldiers or memorializing their sacrifices. Rommel captured images of lone gravesites and secluded makeshift cemeteries in the fields of France and the North African wilderness. Rommel’s photographs show burial services, graves covered with flowers, or German soldiers decorating their comrades’ resting places. Sometimes these German soldiers were buried in open meadows, behind buildings, or in desolate spaces not far from where they fell in France. In North Africa, the graves of the dead were a grim sight, covered by heaps of sand and rocks. Rommel’s pictures show that wooden crosses placed on these graves were frequently blown down by dust and gusting winds. The images also depict German soldiers in North Africa using desert brush to decorate graves in lieu of floral arrangements.

One of the grave photographs with a personal story related by Rommel in his writings is that of Lieutenant Most, killed at Rommel’s side in France in 1940. Most was Rommel’s aide; the two men had crossed the Meuse River together under sniper fire and survived many battles together. Most was gunned down unexpectedly as he stood near Rommel during a lull in fighting. Rommel was shocked by this and witnessed Most’s immediate death despite efforts to resuscitate him. He described Most’s death in his writings, referring to him as a “magnificent soldier.” Most’s grave numbers among those photographed by Rommel; located behind a brick wall in rural France, it is decorated with tulips and a wooden cross.

Due to the high quality of Rommel’s Leica images, many details of the graves were preserved in time, including the names, ranks, and death dates of many soldiers. Even after the passage of more than 70 years, many Germans are still waiting to learn the fate and whereabouts of their relatives who were killed or went missing in action. To assist surviving family members in locating deceased relatives, I donated digitally restored copies of Rommel’s war grave photographs to the German War Graves Commission in 2018.

Officials from the German War Graves Commission were eager to see the photographs that I offered to send to them and welcomed the donation. The work of the commission is to bury the dead and reconnect families with missing soldiers. This work is fraught with many difficulties that arise from wartime conditions and postwar scars. In many cases, German soldiers were buried in remote unmarked graves, or their cemeteries were demolished. People from former Allied and occupied countries are often unwilling or reluctant to return materials to the German families that may assist them in burying their dead. This causes suffering among the soldiers’ surviving relatives, many of whom are now elderly and wait with faint hope for news from the War Graves Commission or the Red Cross even after so many years. Due to confidentiality, it is unlikely that the world will ever learn whether Rommel’s graveside photos reunited any of his soldiers’ remains with their surviving relatives, however, I did receive a message from the German War Graves Commission conveying their thanks.

Aside from soldiers, Rommel the photographer had several other chief areas of interest, including nature, airplanes, machinery, military maneuvers, battle action, and war devastation.

Rommel’s affinity for nature found its way into his pictures. He was an intrepid outdoorsman. Like many Germans, he loved hiking, hunting, fishing, skiing, swimming, and exploring nature. His interest in the outdoors was lifelong and can be attributed to the fact that he grew up in a rural and mountainous region of Germany known as the Swabian Alps. As a young man, he often went on hiking trips, and he continued to involve himself in outdoor pursuits with other soldiers throughout his life and military career. While navigating rough and rugged terrain during his military campaigns, particularly in North Africa, Rommel managed to amass a heap of landscape photography. He photographed sunsets over tanks, rocky ravines, windswept dunes, and blossoming meadows. From the images, it is clear that he always went to great pains to neatly frame every shot. Apparently, the general also had a soft spot for flowers. He strained to take macro close-ups in color of delicate white flower petals and bright golden blooms in North Africa. Rommel’s interest in nature also extended to fauna. Camels, horses, and donkeys number among a variety of animals that Rommel captured in peaceful scenes across war-torn lands. Some camel herds were captured by his lens when he shot images as an aerial photographer.

Rommel frequently made use of a Fieseler Storch aircraft to reconnoiter North African battlefields and surrounding terrain. Most of the time, he piloted the aircraft himself. Rommel had entertained a keen interest in flying since his teens and had made efforts to study the science of flight. As a grown man, he seized opportunities to fly planes. Evidently, he was good at it, since he never crashed despite the many perilous conditions he encountered in North African skies. As usual, Rommel toted his camera along with him in the cockpit and somehow managed to snap a bevy of aerial shots even while maneuvering his plane over battlefields and rugged, windy tundra. He liked to photograph other planes from the air—sometimes as they stood motionless in airfields far below him, and many times as they glided aloft outside his window. At times, he also photographed planes flying over him as he stood on the ground.

Machinery captivated Rommel; he was a gifted engineer who showed great interest in battlefield equipment and in designing fortifications. It would be inaccurate to say that Rommel was fascinated only with tanks. Generally speaking, he photographed anything with wheels, engines, gears, or metal parts—whether intact or in ruins. He took many photos of damaged and derelict vehicles in addition to working ones. Sometimes, he photographed pieces of vehicles blown apart during battle. He had an attraction to tank treads and metal bolts, taking many moody and imposing images focusing on the undercarriages of larger-than-life tanks and their outer steel armor. He also frequently took abstract photographs of trucks and battleships.

Rommel enjoyed capturing vivid scenes of his troops advancing. He frequently accomplished this through aerial photography or by wielding his camera from a moving armored vehicle. He intended to use photos of his maneuvers to document military events that transpired under his command. He photographed scores of motorcycles and tanks speeding across France and North Africa from many striking angles and viewpoints. However, not all of the photos were taken with a military view in mind—Rommel could not resist a good shot. He snapped many oddities that crossed his lens, including goats and dogs interrupting a military march, geometric patterns left by tire tracks, and a sandstorm crossing a desert battlefield.

Battlefield chaos provided the scenes for many of Rommel’s most striking pictures. The German commander dedicated himself not only to successfully devising strategies and leading troops under fire, but to photographing the action as it unfolded. Amid bomb bursts, ear-shattering shell explosions, and gunfire, Rommel risked his life to take compelling photos of hot war zones. Photos frequently show other soldiers around Rommel ducking for cover. Other pictures show men charging forward in assaults or firing mortars and plugging their ears amid sonic blasts and curtains of rising dust. Instead of covering his own ears, Rommel was using his hands to snap Leica pictures. As shells fell, Rommel was quick to capture the explosions and fountains of dark smoke that ensued. Rather than shield himself from enemy fire, Rommel accompanied his men on the front lines and took snapshots of some of their most daring exploits in the thick of fighting.

A sizable portion of Rommel’s photography focuses on the devastation of war. These pictures form some of the strangest and eeriest in his collection. These pictures depict only emptiness and ruin—with isolated human figures making occasional ghostly appearances. Destroyed buildings, collapsed walls, shattered inanimate objects, and bomb-tossed furniture all merited single snapshots from Rommel as he passed by them. The result is a hodgepodge of destruction. Most of these spooky photographs show intellectual contradictions. For example, his photos portray order amid disorder, broken or ruined machines, or neatly intact objects among ruins. One photograph shows a shadowy staircase on fire inside a building. Another depicts a line of torched cars parked in perfect formation along a street. An orderly row of trees in North Africa stands in the sunshine beside a shattered wall. What makes these pictures unsettling is the complete absence of human presence in most of them. It seems obvious that Rommel deliberately excluded people from these scenes, likely out of respect. Doubtless, Rommel as a soldier witnessed much destruction during his career, more so than appears in his collection. Why he chose to capture these particular scenes is a mystery.

Much can be gleaned about Rommel’s personality from the types of photos he did not take during the war. During his lifetime, Erwin Rommel was a man whose personal opinions and point of view were often understated and seemingly repressed. Absence, at times, speaks louder than presence. This is quite true in the case of Rommel’s photo collection. The photographs seized were exactly as they had been in his unaltered personal collection under the care of his family.

Rommel took no photographs of dead people. This is unusual since many war photographers visually document death. Also, many American military officers in World War II took photos of dead enemy combatants. Yet not a single dead German, Italian, or Allied soldier of any type appears among Rommel’s photos.

Similarly, gore has no place in Rommel’s photos. Pooling blood, guts, and gruesome injuries—most certainly a real part of battle—are nonexistent in the field marshal’s collection. The lone exception is the depiction of a wounded German soldier with what appears to be minor bleeding injuries being carried from the battlefield by his comrades. The wounds were a rare sight.

There is a marked absence of sadism. There are no pictures of human beings in demeaning or helpless situations. Photographs of POWs show them being treated respectfully by German soldiers; there are no images of brutality or dehumanization. Inhumane images such as I have described were frequently taken by Nazi devotees or marauding German soldiers. Rommel, however, did not take any such pictures.

There are no photos of debauchery. German soldiers acquired a notorious reputation for taking risqué and bawdy pictures of each other partying in France following their occupation of that country in 1940; many photographed themselves with trophy foreign girlfriends or in the company of prostitutes. German soldiers were known to have behaved similarly in Italy, Greece, and certain areas of North Africa, and many images of this type exist as proof of their behavior to this day. Rommel was present in France, Greece, Italy, and North Africa where many of these events were occurring and must have been aware of them. However, he was clearly preoccupied with his job and made no effort to create or collect photos of revelry in conquered lands.

Rommel also took no propaganda photographs. Although he frequently allowed himself to be exploited by the German government for propaganda purposes, Rommel’s viewpoint expressed through his pictures reveals an absence of Nazi Party aggrandizement. For example, Nazi Party visual propaganda emphasized racial superiority at others’ expense and centered on the cult of Hitler’s personality, in addition to swastika images and slogans. Rommel did none of these things. He took no photographs of his soldiers performing the Nazi salute. He took no photos to stage images of “racial superiority.” Nazi Party heroes and slogans, neo-pagan symbols, and other iconography associated with the Nazi regime are missing from Rommel’s pictures. Rommel’s photography contains limited photos of the swastika; when present, the swastika appears on soldiers’ uniforms, military vehicles, and the German national flag.

In a similar vein, Rommel took no “war trophy” photography. It was typical for many German soldiers, particularly Nazi Party enthusiasts, to take gloating pictures of destroyed cultural landmarks in foreign countries or to photograph themselves striking victory poses in conquered territories. This was not the case for Rommel. His photo collection contains no pictures of himself or others performing acts of personal or propaganda-related cruelty.

In its entirety, Rommel’s photography collection provides a gripping visual history of World War II from the viewpoint of one of the most famous commanders in modern history. The photographs are valuable not only in view of the strategic military mind that created them, but are also silent witnesses to the war as Rommel, a lone figure against a background of vast chaos, experienced it.

It has been said that an image is worth a thousand words. Scenes captured in Rommel’s photography tell us more about him perhaps than any biographical conjecture written about him. A camera is like an open mind—what moments it chooses to dwell on reveal facts about the personality and will behind the shutter-release button. The pictures that Rommel created show us that he was a high-spirited person who tested danger, a keen observer of human irony, and a leader who enjoyed mixing with his troops, but who was drawn to scenes of personal isolation.

During the last year of his life, Rommel unfortunately destroyed many of the papers and writings that might have revealed more of his thoughts and personal convictions. His pictures, however, endure as visual documents of spontaneous and vivid moments that he never got the chance to revise, edit, or refine. His photography is significant and insightful because it gives modern historians a clear and candid view of a military leader who, throughout most of his life, tended to be minimalistic in expressing his mind.

Since the photos have been returned to Germany, it is now up to present and future generations of Germans to examine their nation’s past as captured by Rommel’s camera and develop their own analyses on a part of history that was previously lost.

At the same time, the photos open new doors for historical discoveries, providing numerous opportunities for historians, military enthusiasts, and curious onlookers in America and elsewhere to reinterpret their existing knowledge of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel and his military campaigns. By viewing Rommel’s photographs, onlookers gain a rare opportunity to look through the lens to experience and share the same sights as he did during the war.

Zita Ballinger Fletcher is a first-time contributor to WWII History. She is an expert on photo research and restoration and resides in Washington, D.C. Her four volume series, Erwin Rommel: Photographer, is available from Amazon.com.