By Michael D. Hull

One of the deadliest and most effective airplanes of the Axis powers, the Junkers Ju-87 Stuka, owed its origin to a fearless World War I ace and, ironically, to innovative American aviation visionaries in the peaceful early 1930s.

After shooting down 62 planes, ranking second only to the famous “Red Baron,” Manfred von Richthofen, and surviving the 1914-1918 war, Frankfurt-born Ernst Udet became a stunt pilot and barnstormed over Africa, Greenland, the Swiss Alps, and South America. While visiting the United States in 1931, he observed dive-bombing techniques being developed by the U.S. Navy.

An ebullient, humorous man with a weakness for women and alcohol, and who made many friends in America and England, Udet returned to Germany around the time that Adolf Hitler and his National Socialists came to power. Encouraged by Hermann Göring, aviation minister of the new regime, Udet demonstrated dive bombing. While the U.S. Navy embraced the dive-bombing concept and the Royal Air Force ignored it, certain German leaders showed interest.

Udet received overtures to help recast the German air service. Though not in a hurry to join the Luftwaffe, he offered some far-sighted technical suggestions. One was that Germany should develop a dive bomber. Hitler wanted a “long-range artillery” plane that would complement the German Army for his planned blitzkrieg strategy, so design work went ahead promptly. In April 1935, the Junkers aircraft company produced and flight-tested a single-engine prototype, and thus was born the Ju-87 Stuka. The name was derived from the German word for dive bomber, sturzkampfflugzeug.

Followed by its rivals, the Arado 81, the Heinkel 118, and the Bloehm & Voss Ha-137, the Stuka had inverted gull-shaped wings, an in-line water-cooled, 1,100-horsepower engine, and a large, fixed undercarriage with wheel spats. Manned by a pilot and a radioman-gunner, its wingspan was 45.2 feet, it had a top speed of 232 miles an hour, it mounted three 7.9mm machine guns, and it could carry 1,100 pounds of bombs under its wings and fuselage.

It was a sinister looking aircraft, resembling a flying vulture. Aviation historian William Green called it “an evil-looking machine, with something of the predatory bird in its ugly contours—its radiator bath and fixed, spatted undercarriage resembling gaping jaws and extended talons.” Ironically, early versions of the Stuka were fitted with Pratt & Whitney Hornet and Rolls-Royce Kestrel engines.

Udet, who joined the Luftwaffe in January 1936 with the rank of brigadier, was appointed inspector of fighter and dive-bomber pilots and became director of Reichsmarshal Göring’s technical department. Playing a leading role in the Stuka’s development, the former ace even added air-driven sirens to the undercarriage legs, designed to spread fear and panic when the plane dived. These “Trumpets of Jericho” were to prove remarkably effective in combat. The Stuka was clearly ahead of its competitors, and the first of its type reached the flying units by early 1937.

Simple to maintain and operate, Udet’s dive bomber was to prove effective in the hands of expert pilots. In 80-degree dives to within 2,300 feet of the ground, they could deliver a bomb with an accuracy of less than 30 yards. Even average pilots could achieve a 25 percent success rate in hitting their targets—a far higher proportion than that attained by conventional, horizontal attack bombers.

The baptism of fire for the Luftwaffe’s Stuka squadrons came swiftly when they were deployed to Spain in late 1937 to support General Francisco Franco’s Nationalist forces in the Spanish Civil War. As part of Maj. Gen. Hugo Sperrle’s Condor Legion, which wreaked havoc on Spanish cities and towns, the Junkers Ju-87s were highly effective, despite some shortcomings, against both ground targets and shipping. They flew on every front where German planes served during the brutal war, which served as a valuable training ground for the Luftwaffe.

Stukas had proved their worth in Spain, and production was stepped up. By mid-1939, up to 60 improved “B” models per month were being turned out. They were soon to see action.

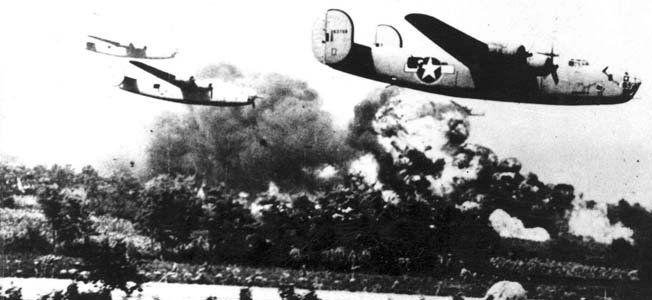

Stukas flew the first combat mission of World War II when 53 German panzer and infantry divisions, supported by 1,600 aircraft, swept into Poland on Friday, September 1, 1939. Three Ju-87B-1s led by Lieutenant Bruno Dilley took off early that day to attack the Dirschau bridge over the Vistula River, about 11 minutes before the Nazis declared war. Accompanying the German ground forces as they surged forward, more of the dive bombers proved deadly as they destroyed Polish tanks and planes on the ground, blasted airfields, bridges, highways, artillery emplacements, supply depots, and troop concentrations, and sank all but two of Poland’s warships. The Luftwaffe committed all nine of its Stuka groups, a total of 319 planes, to the offensive.

The loud sirens of the diving Junkers Ju-87s spread terror among the hapless Polish troops and citizens. Outnumbered and hampered by outdated weapons, the Poles fought gallantly until their government capitulated on September 27. The Stukas gained glowing endorsements for their first major test while helping to speed the German victory, and Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels boasted that the Junkers Ju-87 dive bomber was invincible. Like the panzer, the Stuka quickly emerged as a highly visible symbol of Nazi aggression as it spread destruction and terror.

During the 1939-1940 “Phoney War,” a relatively calm period followed the fall of Poland. That ended with a bang on Friday, May 10, 1940, when Nazi Germany launched blitzkrieg (lightning war), with panzer, infantry, and airborne forces of Army Groups A and B, led by Generals Gerd von Rundstedt and Fedor von Bock, respectively, smashing their way westward into Holland, Belgium, and Luxembourg. Almost all of the 380 available Stukas were initially concentrated against Holland and Belgium. The planes provided close air support for airborne troops landing at several points. It was not the most effective way to use the Ju-87s, but there was no alternative. The lightly armed paratroopers relied on the dive bombers for their heavy punch.

Some of the planes took part that fateful day in one of the most spectacular operations of World War II. When specially trained German glider-borne infantry landed atop the fortress of Eben Emael, at the confluence of the Albert Canal and the Maas River in Belgium, and seized it, nine Stukas of Lieutenant Otto Schmidt’s Geschwader 77 lent support by hitting a Belgian Army position near the canal.

In France, as in Poland, the screaming Stukas had a terrifying effect on both troops and civilians. A French general reported that his men simply froze in place as waves of Ju-87s plummeted toward them. “The gunners stopped firing and went to ground, the infantry cowered in their trenches, dazed by the crash of bombs and the shriek of the dive-bombers,” he said. “They had not developed the instinctive reaction of running to their antiaircraft guns and firing back…. Five hours of this nightmare was enough to shatter their nerves.”

In the following weeks, as the German forces ground on westward, the Stukas reverted to their more usual targets in rear areas. They were in action constantly when the weather permitted, and the crews sometimes flew as many as four sorties a day.

By the final week of May, the Allied troops in northern France were falling back on the Channel port of Dunkirk, where an evacuation operation was started on May 27. The enemy bombers and Stukas managed to cause severe damage to ships and harbor installations.

When the evacuation ended at dawn on June 4, 1940, almost 340,000 British and French troops had been rescued by Royal Navy destroyers and a motley fleet of civilian launches, motorboats, ferries, and yachts. The Stuka squadrons had again proved their worth, and now they prepared to assist in Operation Sealion, Hitler’s planned invasion of England. But their fortunes were about to be dramatically reversed when they faced strong fighter opposition during the Battle of Britain.

History’s first great aerial campaign opened in July 1940, with small-scale German attacks on coastal shipping in the English Channel. On the afternoon of July 13, half a dozen Stukas of Geschwader 1 pounced on a convoy off Dover. Eleven RAF Hurricanes broke up the attack and damaged two Ju-87s, and no ships were hit. But escorting Messerschmitt Me-109 fighters intervened and shot down two Hurricanes.

The pace of the air fighting gradually accelerated, and the Luftwaffe mounted its heaviest convoy attack on August 8. That morning, a few Stukas tried to reach the 18 freighters and naval escort of Convoy CW-9 as it headed west toward Weymouth, but they were driven away by patrolling Spitfires and Hurricanes. At midday, however, the Luftwaffe launched a heavier assault, with 57 Stukas diving on the convoy as it passed off the Isle of Wight.

While the Me-109 escorts tangled with RAF fighters, the Stukas fell upon the slow-moving ships. Several were damaged and two sunk. During the afternoon, 82 more Ju-87s went in to finish off the surviving vessels. The convoy was almost annihilated, and only four ships reached Weymouth without damage. But the Germans had lost 28 aircraft, including nine Stukas downed. Ten others were damaged. The RAF lost 19 fighters that day.

The largest Ju-87 attack during the Battle of Britain came on August 18, which went down in history as “The Hardest Day.” Early that sunny afternoon, 109 Stukas drawn from three groups of Geschwader 77 set out to bomb the radar station at Poling and airfields at Gosport, Ford, and Thorney Island in southeastern England. Fifty Me-109s provided protection. As usual, the raiders hit their targets with precision, but scrambling Hurricanes from the RAF’s No. 43 and 601 Squadrons charged into the German formations with their machine guns belching fire.

Lieutenant Frank Carey, who led the Hurricanes of No. 43 Squadron, reported later, “In the dive, they [Stukas] were very difficult to hit, because in a fighter, one’s speed built up so rapidly that one went screaming past him. But he couldn’t dive for ever.” One by one, flaming Stukas went down. As the surviving Ju-87s headed south for their French bases 70 miles distant, the Hurricanes ran out of ammunition and broke off the chase.

It was a black day for the Junkers dive bombers. Sixteen were shot down, and seven limped home with damage. The first real setback suffered by the Stuka groups highlighted the plane’s major weakness, which would be demonstrated repeatedly as the war progressed. While it was a deadly attack weapon, it could operate only when escorted, when there was no interference from enemy fighters, and when its targets were not well protected by antiaircraft guns.

At the height of the Battle of Britain on August 13-18, a total of 41 Stukas were shot down by Spitfires and Hurricanes, and the losses were regarded by the Luftwaffe high command as unacceptable. The planes were needed to counter the might of the Royal Navy during the imminent invasion of England, so it was decided to preserve the dive-bomber force. The Junkers Ju-87s were withdrawn from the Battle of Britain and played little further part in it. RAF Fighter Command’s eventual triumph over the Luftwaffe in September 1940 forced Hitler to shelve Operation Sealion, but the Ju-87’s career was far from over. Vital roles awaited it the following spring and summer in the Mediterranean, the Balkans, and Russia.

During the bitter campaign on Crete in April-May 1941, when British and Greek troops were forced to evacuate after failing to dislodge the Germans, Stukas caused heavy losses to Royal Navy ships. Three cruisers and six destroyers were sunk, and 13 other vessels were severely damaged, including the 23,000-ton carrier HMS Formidable.In the Western Desert, meanwhile, Ju-87s flew numerous sorties in close support of General Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps during its long, seesaw struggle with British and Commonwealth forces. The planes destroyed many British strongpoints with incredible accuracy.

By 1941, however, the Stuka was virtually obsolete. It had an unfortunate tendency to disintegrate when struck by Hurricane machine guns, and its 120-mph climbing speed was too slow to qualify for escort by fast fighters such as the Me-109. RAF pilots breezily relished “Stuka parties” as a form of risk-free recreation, while the Stuka crews joked wryly that their planes were so sluggish that survival depended on their British opponents overshooting.

Nevertheless, the Ju-87s continued in their role of attacking Allied land and sea targets and as “flying artillery” spearheads wherever German forces launched offensives. When three powerful German army groups smashed their way into the Soviet Union on Sunday, June 22, 1941, eight Stuka groups with a total of 324 planes flew in close support. They bombed Russian installations and towns as the panzer and infantry columns raced forward against sparse opposition.

“At first, things were easy in Russia, and we had few losses to either flak or fighters,” reported Hauptmann Schmidt of Geschwader 77. “Gradually, however, the Russian gunners gained experience in dealing with our diving tactics. They learned to stand their ground and fire back at us, instead of running for cover as others had done before…. A further strain was caused by the knowledge that if one was shot down on the enemy side of the lines and captured, the chances of survival were minimal.”

As the grinding war of attrition continued across the vast Russian steppes, modified versions of the Stuka were rushed into frontline service. They included the Ju-87 “Dora” and the Ju-87G “Gustav.” Filling the desperate need for a tank-busting airplane, the Gustav carried a 550-pound high-explosive bomb and mounted two 37mm high-velocity cannons under the wings. The guns proved highly effective in piercing the relatively thin armor on the rear of Red Army tanks. The Gustavs made a timely appearance in the spring of 1943, shortly before the main German offensive, Operation Citadel, aimed at the central front near Kursk.

All available Stuka units, with a total of about 360 Doras and a dozen Gustavs, were positioned to support the offensive. What developed into the biggest tank battle in history commenced on July 5, 1943. With their crews flying up to six sorties a day, bomb-carrying Doras attacked targets in the Soviet rear areas while the Gustavs went after enemy tanks caught in the open. Despite powerful air support, however, the German armored thrusts became bogged down in the Soviet defenses. With the last reserves fully committed, Hitler ordered his army to move to the defensive on July 23. At Kursk, the German Army failed to produce a decisive victory, and it never regained the strategic initiative.

On the Eastern Front, a Stuka pilot emerged as the leading combat ace of World War II. He was Oberst Hans-Ulrich Rudel, a once timid minister’s son who flew an incredible 2,530 sorties, dived lower than anyone, and pioneered a ground attack technique. Like a one-man air force, he destroyed 519 tanks, more than 2,000 vehicles, many artillery positions, and even a Soviet battleship, the Marat, and a cruiser. Rudel was the sole recipient of Germany’s highest decoration, the Gold Oak Leaves with Swords and Diamonds to the Knight’s Cross. After losing a leg, he disobeyed orders from Hitler and Göring and continued to fly until the last day of the war. Rudel was reported to be Hitler’s choice to succeed him as führer.

In the autumn of 1943, the Luftwaffe reshuffled the tactical support units, with ground-attack Focke-Wulf 190Fs beginning to replace the Ju-87 Doras. Arguably the best German fighter of the war, the FW-190 mounted four 20mm cannons and two machine guns, carried up to 1,100 pounds of bombs, and was twice as fast as the Stuka.

Elsewhere, from Athens to Corinth and Malta to Tobruk, Stuka squadrons continued to give sterling service. They escorted convoys, raided Allied bases and shipping in the Mediterranean area, and harassed British Eighth Army troops and installations during the long war in the Western Desert. After Operation Torch, when U.S. forces invaded North Africa to join the British, inexperienced GIs felt the wrath of Ju-87s, particularly during the rout of the U.S. II Corps at Kasserine Pass.

The last of more than 5,700 Ju-87s came off the production lines in September 1944, but the type continued in service. Some were modified as night raiders, many were employed as glider tugs, trainers, and transports, and the Ju-87C, equipped with folding wings and a tail hook, was developed to operate from the German aircraft carrier Graf Zeppelin. The ship was never commissioned.

But the heyday of the Stuka, which had been supplanted by faster and more powerful planes, was over. By April 1945, the last month of the European war, only 125 Ju-87 Doras and Gustavs remained with frontline units. Besides the Luftwaffe, Stukas flew during the war with the air forces of Italy, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, and Croatia.

The plane that had spread so much terror and destruction from Warsaw to Crete to Stalingrad, symbolizing Nazi might and ruthlessness, outlived the man who masterminded it. Ernst Udet, one of the most important planners of the Luftwaffe, along with Göring and the stocky, able Erhard Milch, was appointed chief air inspector-general of the Reich Air Ministry in February 1938. He was in charge of aircraft design, production, and procurement.

But his career in preparing the Luftwaffe for the coming war was stormy. He drove himself to the limit as chief of supply, but he became a shadow of his former self, and his buoyant personality cracked under the strain. Udet overindulged in cognac and turned to drugs. On November 17, 1941, he committed suicide.