By Steve Ossad

After leading his U.S. 3rd Armored “Spearhead” Division on the longest, one-day, enemy-opposed mechanized advance in American history, Maj. Gen. Maurice Rose was killed in action on March 30, 1945, one of 30 flag officers who fell in World War II, and the only armored division commander ever lost in combat.

However, the march of the 3rd Armored Division did not end with the death of its commander or before its men confronted the full meaning of Nazism. Like other fighting divisions, the various units within 3rd Armored prepared after-action reports for April 1945 that document military operations, including liberations, but the official records, archival sources, personal memoirs, photos, etc., vary considerably concerning discovery of the atrocities and the actual places where the horror was perpetrated.

As one example, the 82nd Airborne Division final after-action report (AAR) contains a single paragraph in the Military Government section about “the discovery of a concentration camp at WOBBELIN” and the medical and humanitarian efforts undertaken, including a forced reburial of victims by the local population, a virtual constant in American AARs. In the case of the 3rd Armored Division, the recollections of individual soldiers, unit AARs, and the semi-official history, Spearhead in the West, offer a more detailed description of the liberation of a notorious concentration camp as part of military operations in the last days of the war in Germany—less than two weeks after Maurice Rose, the highest ranking Jewish American officer in the U.S. Army, was cut down in combat in the act of surrendering.

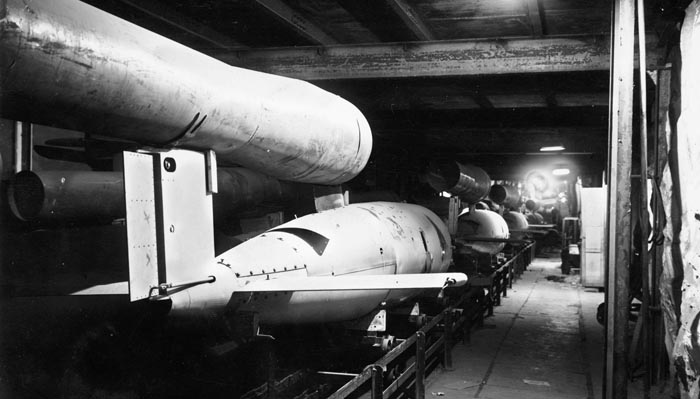

KZ (Konzentrationslager, i.e., Concentration Camp) Dora-Mittelbau was built in central Germany near the town of Nordhausen, by which name the entire camp complex is now commonly, but erroneously, known. The blandly named Mittelbau (translation, “central construction”) camp was initially established as a sub-camp of KZ Buchenwald, when the SS sent a detail of 120 slaves to expand a large underground Wehrmacht fuel depot to produce V-2 ballistic missiles after the existing production sites became the target of Allied bombers. When the main V-2 effort shifted from Peenemunde to Mittelbau, the site became an independent concentration camp in late October 1944, eventually encompassing more than 40 subcamps of its own, spread out over the immediate area. The first inmates, who built the facilities, were initially kept underground in the dark, unventilated tunnels, referred to as “Dora” in official documents of “Mittelbau GmbH,” the business unit set up by Armaments Minister Albert Speer’s vast empire, which oversaw the production site. The main factory area inside the tunnels was often referred to as Mittelwerk (“middle works.”) The SS ran all the camps, provided the slave labor at very reasonable negotiated rates, and the supply was constantly “replenished.”

Brutalized in miserable conditions, with minimal food, sanitation, heating, or light, the condemned slaves slept on wood racks, four levels high. The daily ration consisted of four ounces of black bread and a liter of potato soup—the former more sawdust than flour, and the latter diluted foul water without nourishment—which only stoked the constant hunger and dysentery. Industrial-level noise from moving and operating heavy manufacturing equipment and blasting though rock never ceased, and the air was befouled by noxious and deadly gases from explosives, fuel, and toxic metal dust. Vermin of all kinds and diseases long thought eradicated, such as tuberculosis, typhus, and pneumonia, flourished. The daily death rate during early construction and the last few months of the war soared, and the used-up slaves were “selected,” temporarily warehoused near the rail tracks, and shipped to KZ Mauthausen and other places for extermination.

Once full V-2 production began in the autumn of 1944, the Mittelbau complex held about 20,000 slaves, most working on outdoor construction, and about 6,000 in the tunnels. Dora-Mittelwerk produced 600-700 missiles per month on average, short of the monthly goal of 900 but nevertheless a significant achievement, especially after the Luftwaffe commandeered 40 percent of tunnel capacity for Junkers aircraft engine assembly. The enterprise was a model of efficiency, earning official commendations for the top managers, engineers, and SS staff, several of whom, including the last commandant, were prominent Auschwitz veterans.

The first V-2 rockets struck London on September 8, 1944, with the final launches on March 27, 1945. In the nearly seven months of attacks more than 3,000 warheads hit Allied cities, including Antwerp, Liege, and Paris. The ballistic missiles targeting London, most of which were produced in the Dora tunnels, killed about 2,500 civilians, injuring more than 6,000. During its existence as an underground, state-of-the-art, slave-based multi-facility manufacturing site—the final evolution of the SS master-slave economic system—more than 20,000 people from all over Europe were murdered or died from starvation, disease, or random executions at KZ Dora-Mittelbau, a labor cost of seven to eight slaves per V-2 rocket, which would kill or wound three to five civilians.

In early April 1945, as the Allies approached, consistent with Reich policy to leave no evidence of the mass murder behind, the SS began evacuations of the Dora-Mittelbau inmates north to KZ Bergen-Belsen, a mass collection point for the surviving prisoners of the crumbling Nazi empire. Thousands were murdered before and during the death marches, and by the time American forces arrived at Nordhausen few living prisoners remained. The 3rd Armored Division first entered the camp complex at an accidentally bombed and ruined barracks overflowing with corpses, called the Boelcke Kaserne.

Brigadier General Truman E. Boudinot, one-time champion Army free balloon racer and veteran tank commander of Combat Command B (CCB), one of two brigade-sized striking forces of the 3rd Armored “Spearhead” Division, had been driving his men hard for weeks. Starting with the breakout from the Remagen Bridge in early March 1945, the division spearheaded VII Corps, First Army, the southern pincer of 12th Army Group’s tightening grip on the industrial Ruhr region where the remnants of several German armies were trapped. When 3rd Armored met the tanks of the northern pincer, the U.S. Ninth Army led by the 2nd Armored “Hell on Wheels” Division, on April 1, 1945, the escape route slammed shut on the greatest encirclement battle in American history, with more than 350,000 prisoners bagged and German Army Group B destroyed. Field Marshal Walter Model, known as “Hitler’s Fireman” and the longtime battlefield opponent of Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley, killed himself rather than surrender. Although the bloodletting would continue without pause until 3rd Armored reached the town of Dessau on the Elbe, the original mission of General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s SHAEF was essentially complete. The industrial heart and war-making capability of the Third Reich, and its armed forces in the West, had been destroyed.

A week and a half after closing the Ruhr Pocket, General Boudinot was attacking into the Harz Mountains, where the high command believed strong German forces were gathering. Early on April 11, 1945, he received orders to take the town of Nordhausen. The rest of 3rd Armored, now commanded by Brig. Gen. Doyle O. Hickey, would continue the attack toward the mountains. The two task forces of CCB were built around Colonel John C. Welborn’s 33rd Armored Regiment and Lt. Col. William B. Lovelady’s 3rd Battalion and were moving abreast on two easterly routes. Lovelady entered the town near the railroad tracks and marked it on his map as a Luftwaffe base. He reported a large prison-type compound and requested more infantry support from Maj. Gen. “Terrible” Terry Allen’s 104th “Timberwolf” Infantry Division, which was attached to VII Corps and moving to the north.

The main Mittelbau camp was surrounded by an electrified barbed-wire fence and watchtowers. A large roll call area, where prisoners were assembled and counted several times a day, was located just west of the main entrance. The SS guard quarters lay farther east, outside the wire, where resistance was scattered, disorganized, and brief. No elements from the German Eleventh Army were encountered. Northeast of the main camp, from which the slaves were marched to work at 0400 and 1600 hours for 12-hour shifts of hard labor every day, camouflaged entrances led to the underground factory manufacturing Hitler’s “weapons of retaliation” (Vergeltungswaffen), the 40-foot-high V-2 ballistic missile packing 1,600 pounds of high explosive and the V-1 early-generation cruise missile (known as the flying bomb or “doodlebug”). The capture of Dora and the V-2 assembly plant at Kleinbodungen were major strategic prizes for Allied air technical intelligence officers looking for missile and aircraft materials and personnel. Even as the war in Europe ended, each of the Western Allies and the Soviets were competing for technological advantages in the next, and colder, struggle to come.

At the deepest level of the underground complex ran two enormous shafts, dug 600 feet into a limestone ridge, each more than a mile long, more than 50 feet high, and housing a full assembly line, one for V-1s, the other for V-2s. Dozens of 500-foot-long cross-tunnels linking the main shafts were filled with machine tools and bomb-making material at various stages of production. German engineers had already begun experiments on a secret V-3 antiaircraft missile system. That program and the V-2 assembly plant and storage facilities claimed the most able-bodied of the slaves, mostly Reich political prisoners under the Nebel und Nacht edict, Polish and Soviet prisoners of war, a small number of specially selected Jews, and forced laborers from the conquered countries who dug the tunnels and were then worked to death on the production lines.

Scattered inventory, and especially German scientists, were immediately secured and put under guard. Tons of documents and as many as 100 intact V-2s were crated and shipped back to the United States. Secrecy under the code name Operation Paperclip descended on Dora-Mittelbau with the birth of the American missile and, eventually, space programs, which would be run by some of the murderous Nazi masters of the tunnels. First among the known war criminals was SS Major Werner von Braun, who was a full and willing partner in all the camp’s operations and atrocities. The American intelligence officers and government officials knew who their new partners were. Von Braun’s deputy, Helmut Gottrup, was captured by the Soviets and became a hero of their space program.

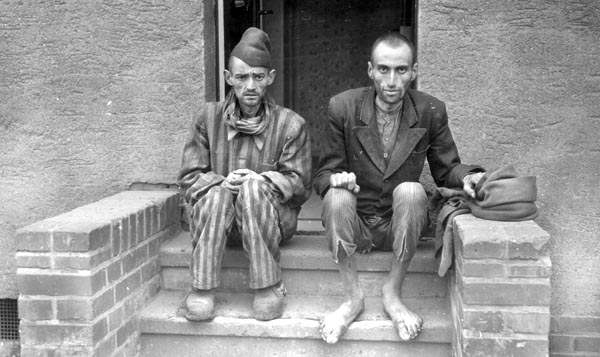

So terrible was the magnitude of what General Boudinot saw that day that he ordered the headquarters company photographers and MPs, as well as the newsmen, to gather evidence. The dead were left where they lay. A brief film called The Liberation of Nordhausen and later film compilations showing the camp and shot by the division and corps cameramen are still powerful testimony. Even for veterans of the most gruesome armored combat, men used to violent death and the human wreckage and casual brutality of the battlefield, the conditions they encountered left them shaking with rage, some openly weeping. As they progressed through the place, the troops eventually discovered more than 5,000 bodies in the partially destroyed barracks, lying about or stacked for burning at the crematory located in the north of the main camp. The very few alive lay scattered among the mass of corpses, as described in the division official history: “Emaciated, ragged shapes whose fever-bright eyes waited passively, even in the same beds with their dead and dying comrades, too weak to move. Over all the area clung the terrible odor of decomposition and, like a dirge of forlorn hope, the combined cries of these unfortunates rose and fell in weak undulations. It was a fabric of moans and whimpers, of delirium and outright madness. Here and there a single shape tottered about, walking slowly, like a man dreaming.”

To the starving and half-crazed inmates, the arrival of the soldiers and vehicles bearing the white star was a miracle from God. Men barely able to move kissed the filthy boots of the soldiers, murmuring their prayers of thanksgiving in a Babel of languages. One group of hysterically happy liberated souls attempted to hoist Lieutenant Herbert Gontard onto their shoulders. Although he was a slim young man, the weakened laborers could not lift him off the ground. Sergeant Ragene Farris, a medic in the 329th Medical Battalion, saw “rows upon rows of skin-covered skeletons … men lay as they had starved, discolored, and lying in indescribable human filth. Their striped coats and prison numbers hung to their frames as a last token or symbol of those who enslaved and killed them…. I noticed one girl. I would say she was about seventeen years old. She lay where she had fallen, gangrened and naked. I choked up, couldn’t quite understand how and why anyone could do these things…. We went downstairs into a filth indescribable, accompanied by a horrible dead-rot stench…. One hunched down French boy was huddled up against a dead comrade, as if to keep warm…. It was like stepping into the Dark Ages to walk into one of these cellar-cells and seek out the living.”

Medics removed 250 starvation cases immediately and hastily set up emergency hospitals. Less severe cases of all sorts were treated on site, but for many there was no hope. Major Martin L. Sherman, a doctor in the 3rd Armored’s 45th Medical Battalion, estimated that even with immediate assistance no more than half the starvation patients would survive. General Hickey, teeth tightly clenched on his ever-present pipe and accompanied by his corps commander, Maj. Gen. J. Lawton “Lightning Joe” Collins, toured the barracks. Collins was sick to his stomach and ordered Colonel Dell B. Hardin, his G-5 officer (civil affairs and military government) to round up all the male citizens of Nordhausen, the most prominent in the front, and force them into the camp.

That night Collins wrote to his wife, “We had the Burgomeister [sic] set aside a plot of ground overlooking the town, and these people were required to dig graves and carry every one of the dead up the hill and bury them. The local officials disclaimed any knowledge of the camp, which was, of course, tommyrot. We are going to require them to erect a monument in this cemetery as a memorial to these dead.”

Troops who liberated the camp, especially Colonel Lovelady’s men who saw the Boelcke Kaserne, were infuriated when the local citizens insisted that they knew nothing of the atrocities. Private Harold Kennedy, one of Terry Allen’s foot soldiers, saw the camp a few hours after liberation and could not believe the German civilians. “They always said, ‘Well, we didn’t know.’ And I’d say, ‘You could smell it, couldn’t you?’” Lou “Louch” Baczewski, a Task Force Lovelady Sherman tank driver, describing decades later what he saw and smelled at the ruined barracks to his grandson, was overcome several times by the telling, rubbing his forehead, repeating over and over, “It was a bad sight. It was a bad sight. It was something terrible.”

Still angry about the murder of General Rose just days before, the 3rd Armored needed no urging to get back into the fight and were in a “savage mood” as they went into the final battles. Several captured German scientists were publicly beaten for benefit of the cameras, and unconfirmed reports circulated that few prisoners were taken in the days immediately following the camp’s liberation. After pausing for several hours to refuel, reload, and grab some rest, the VII Corps advance resumed early on April 12, 1945, the 3rd Armored Division Forward HQ entering Sangerhausen, 22 miles to the east, by midday. The Ruhr Pocket battle was eventually renamed the Rose Pocket to honor the fallen 3rd Armored commander. The war—and the killing—went on for another day. But not at KZ Dora-Mittelbau.

At a veterans’ reunion to research the biography of Maj. Gen. Maurice Rose, a man came up to the author and introduced himself as Michael Kane, son of Lt. Col. Matthew Kane, commander of Task Force Kane, 32nd Armored Regiment. Hero. Michael’s mother had recently told him that his father, a traditional and tough Texas West Pointer who passed away when the boy was 10, had helped liberate the concentration camp at Nordhausen. She was concerned that revisionists were already claiming that the Holocaust had never happened. He was struck by her concern—she had never mentioned it or showed any interest—in truth he thought her conventionally, and passively, anti-Semitic. But now, facing death, she wanted her son to know his father’s direct role as a “liberator.” Michael was so engaged by the experience that he went to the reunion to prepare for a trip to Germany to commemorate the liberation of Nordhausen and to see the camp for himself. He wanted to tell the story.

On January 27, 1945, the Red Army liberated the death camp of Auschwitz-Birkenau, the last of the six SS extermination camps (Vernichtungslager), all on Polish soil, as well as many other horrible places in Germany. During the final six weeks of the war in Europe, American and British units liberated many of the main concentration camps as well as the network of sub-camps, slave labor, brothels, prison camps, and a dizzying array of other terrible facilities. Popular history has concentrated on a few notorious names, especially the first camps discovered, like Dachau and Buchenwald, but recent scholarship establishes that the Nazi system encompassed more than 40,000 separate installations with a death toll far beyond the latest generally accepted numbers.

Liberation was not limited to places of persecution, and a few days after taking Dora-Mittelbau the 3rd Armored Division freed 450 British POWs at Polleben, some having been captured at such early battles as Dunkirk, Norway, and Crete. The British 11th Armoured “Black Bull” Division liberated KZ Bergen-Belsen, burning that name in the British consciousness along with the image of bulldozers pushing thousands of emaciated corpses into a ditch.

On April 12, 1945, Supreme Allied Commander General Eisenhower and Generals Omar Bradley and George Patton went to KZ Ohrdruf, a sub-camp of Buchenwald and the first to be liberated by Patton’s Third Army, to see for themselves. Bradley recalled the moment in his first memoir. “Eisenhower’s face whitened into a mask. Patton walked over to a corner and sickened. I was too revolted to speak.” They saw the evil they had defeated on the battlefield. As testimony, the surviving work of the U.S. and British cameramen created exactly the images that the generals and newsmen wanted and that mankind still needs to see, especially when Holocaust denial and ignorance is growing in the United States. Even more chilling, in the lands where the crimes happened, some groups celebrate the murderers with parades, statues, and dishonored flags.

The Center of Military History of the United States Army, advised by the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, has credited 36 U.S. World War II Divisions—24th Infantry, 10th Armored, and 2nd Airborne—as “liberators,” and their flags, adorned with campaign streamers, stand in honor at the museum in Washington, D.C.

Author Steve Ossad has recently written a biography of General Omar Bradley published through the University of Missouri Press. He resides in New York City.