By Tim Miller

What began as a polite truce between armies that allowed each to draw water from the same river turned into the battle that would give Greece to Rome. After a Roman mule escaped across the water into the lines of the Macedonians, one Macedonian ally ended up dead, and the whole army began crossing for revenge. It almost could have been planned, for both the Romans and Macedonians were impatient to get on with the battle.

By the spring of 168 bc, Macedonian King Perseus had been complicit in the execution of his brother and, by extension, the early death of his father, Philip V. In the decade since his ascension, Perseus had been able to fill the coffers of Macedonia, increase its military force, and swell the home front population with disaffected people from all over the Aegean. He achieved this despite the growing influence of Rome in Greece and the Balkans and the resistance from neighboring Greek states.

When the complaints of neighboring states had brought Roman armies to Greece, Perseus had defeated them all, though never decisively. At last, on a scorching day in late June, as he led his army across the Leucus River in Macedonia, just south of the city of Pydna and not far from the Gulf of Thessalonica, that decisive battle was finally at hand. The battle pitted Macedonian King Perseus’s 40,000 troops against Roman Consul and General Lucius Aemilius Paullus’s army of nearly equal strength.

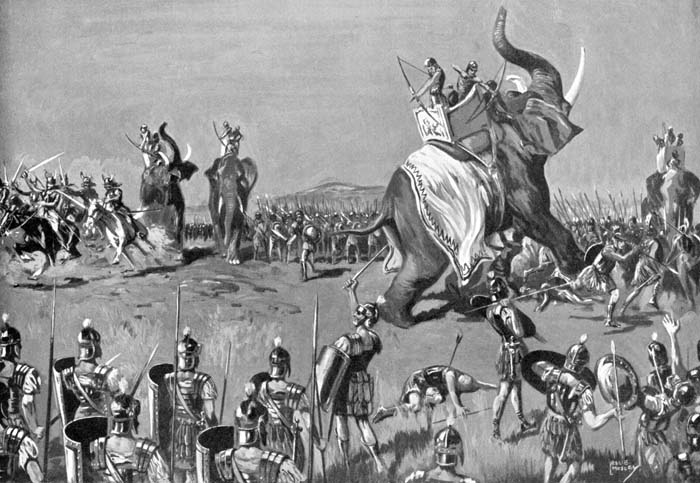

As the Romans began to gather themselves, they must have wondered what advantage Perseus had gained by crossing the river to attack the Roman camp, which lay at the foot of Mount Olocrus, since they had given up the more level terrain in the fields south of Pydna. Paullus watched in awe as the Macedonians advanced boldly through the water. The first phase of the battle went badly for the Romans, for they were driven up the mountain. The Romans had also brought along 20 war elephants, but they were of questionable value on the mountainous terrain.

It was not long before Perseus’s assault began to falter. As each section of the Macedonian army encountered uphill terrain and varying degrees of Roman resistance, the men rushed ahead or lagged behind those beside them. What had been a successful push became a wildly uneven one, and gaps began to appear in their battle line. The Roman commander saw this development and immediately ordered his men to thrust themselves into the gaps to engage them in hand-to-hand combat. In this way they would not be “fighting a single battle against them all, but many separate and successive battles,” wrote Roman historian Plutarch. In those gaps, the successor state Macedonia, established on the death of Alexander the Great, came to an end.

In 168 bc Rome was barely 30 years removed the Second Punic War, that traumatic but ultimately victorious struggle with the Carthaginian general Hannibal. Hannibal was a tactician of particular genius who wreaked havoc through Roman Spain. He crossed the daunting Alps with his army and descended into northern Italy where he nearly wiped out the Roman army first at Lake Trasimene and again at Cannae. Yet in the end the Romans prevailed.

When a Roman army under the command of Cornelius Scipio Africanus crossed to north Africa and threatened Carthage in the way Hannibal had always hoped to threaten Rome, he abandoned Italy and was eventually defeated at Zama in 202 bc. Hannibal remained for the time being in Carthage; however, when Rome became worried over a resurgence of Carthaginian influence in the Mediterranean, they demanded Hannibal surrender to them. But Hannibal went into voluntary exile and was received into the court of King Antiochus III, the ruler of the Seleucid Empire.

With Carthage no longer a threat, Rome suddenly found itself in the position of a Mediterranean and Aegean power, a position that needed constant defending and refinement. As such, the countryside of Italy was emptied of men either because their land had been destroyed during the war or because they were recruited for the army. Thus, Rome came to depend upon slave labor as it never had before, as well as the continuation of war. As a result of these pressures, Rome’s burgeoning democracy was jeopardized. The death of the Roman Republic would occur less than two centuries later. For the time being, though, Rome fought abroad against aggression in order to maintain stability in a nearby region. It had no interest in conquering and assimilating new territories.

The pressure to become involved in foreign wars began almost immediately after Hannibal was defeated at Zama when Rome was dragged into defending the kingdom of Pergamum in northeastern Anatolia and the island kingdom of Rhodes in the Agean Sea. Both of these minor kingdoms appealed to Rome for help when Philip V of Macedonia began threatening them. Rome feared that if they fell, it would not be long before Philip tried to move into Italy itself.

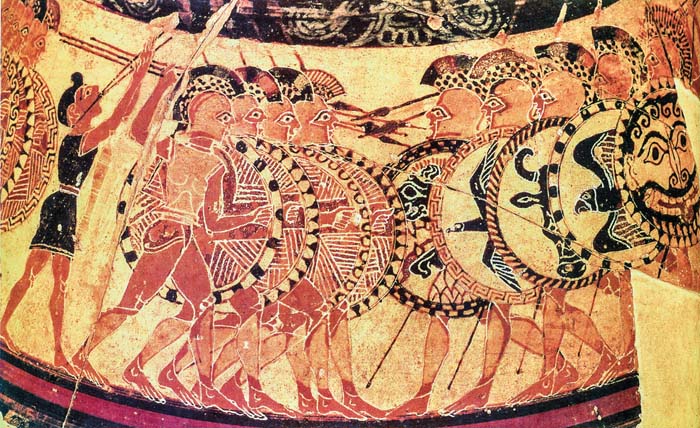

The Romans soundly defeated Philip at Cynoscephalae in 197 bc. Rome won the battle primarily because of the characteristics of its army. The Roman army was based on the maniple formation. Although the Romans were organized in squares as the Greeks were, the maniple was a more versatile formation on the battlefield. The Roman soldier fought with a short, double-edged sword known as a gladius. Armed with the gladius and fighting in the maniple, the Roman troops were able to manuever more easily than the Greek soldiers, who were armed with 21-foot spears known as sarissas. The Greeks, who were packed tightly together, could only fight from the front with their long spears. If attacked in the flank or rear they were in serious trouble.

Another Roman ally in the Aegean, the Aetolians, upset over the terms that Philip V was granted, entered into negotiations with Antiochus. He saw an opportunity to break into Anatolia and hence Greece by defeating the Romans.

In 190 bc Antiochus met a Roman and Greek army commanded by Consul Lucius Cornelius Scipio on a field of battle at Magnesia in Lydia in western Anatolia.

In that sanguine contest, the Roman infantry contained the attack of Antiochus’s Macedonian-style phalanx. Although Antiochus led the cataphracts in a charge that punched through the Roman infantry, he wound up behind enemy lines facing the well-defended Roman camp. Unable to take the camp, he was boxed in for the duration of the contest.

The battle was decided in the contest between the Roman right wing’s cavalry and Antiochus’s left wing consisting of half the heavy cavalry, elephants, chariots, and skirmishers. The Roman light infantry’s missile attack startled the elephants. The great beasts, which were driven back on their own troops, broke up the Seleucid phalanx attack. Having eventually fought his way out of the Roman rear, Antiochus returned to his army to find that his left had collapsed. He fled the field and the Romans captured his camp. It was a battle full of portent for it showed that it was no easy task bringing a phalanx to bear against Roman legions.

The Romans demanded that Hannibal be handed over to them since it was well known that he had been advising Antiochus for the past five years. As it happened, Hannibal had foreseen this event and escaped. He ultimately committed suicide in Bithynia rather than fall into Roman hands. But Rome also demanded that the Seleucid Empire abandon all Asian land west of the Taurus Mountains. This once again isolated the Balkans and the Peloponnese from outside forces while also putting Rome in the position of having to be available to oversee any developments. The lesser kingdoms, like Rhodes and Pergamum, also favored Rome’s help in part because it did not desire to annex them.

The region was convulsed by instability for the next 20 years. Greece and Anatolia by this time had very nearly become areas of Roman administration. As such, the Romans could no longer ignore internal squabbles of minor powers or even the most seemingly petty appeals if they were to maintain order.

Among the various quarrels that surfaced were complaints made by the Thessalians against Philip V. Rather than sending an army, though, Rome dispatched embassies to investigate each complaint. Philip saw this as a sign of Rome’s weakness and attempted to regain power. He told one Roman delegation that “his days had not yet set,” according to Roman historian Livy.

To stall for more time, apparently to build up an army, he sent his youngest son, Demetrius, to Rome to make Philip’s own case for authority in the area. However, Philip’s oldest son, Perseus, jealous of his younger brother’s successes and the attention he was receiving, fed such convincing lies to his father that Philip had Demetrius poisoned. Philip, learning almost immediately that Perseus had lied to him, sank into a haunted depression and died in 179 bc.

Perseus was now ruler in Macedonia, and he saw no reason to end his country’s enmity for Rome; however, he made sure to officially renew the same terms of alliance with Rome that this father had, if only to present a good face. Meanwhile, he shored up the support of many of Greek states and did so by never once resorting to battle. Instead, he took advantage of the fact that Roman policy in Greece and the Balkans had forced many erstwhile mercenaries to cease their activities.

The new Macedonian ruler made a call for all such people to come to Macedonia and in general asked for the support of anyone who had become a political exile or gone into impossible debt thanks to Roman incursion in the area. Even as the Achaean League officially denounced Macedonia in 175 bc, Perseus was still able to create an anti-Roman fifth column in every city throughout an area to which Rome only recently thought it had brought peace.

The Romans dispatched commissioners to Greece to assess its current political environment. In the meantime, King Eumenes travelled to Rome where he presented a detailed list of Perseus’s crimes to the Roman Senate. Ambassadors from Rhodes, also present, accused Eumenes of the very crimes of which he was accusing Perseus. The senators chose to believe Eumenes over the Rhodians. On his way back to Pergamum, and at the Oracle of Delphi no less, Perseus arranged for an attempt to be made on his life. By that time, the Romans had begun to fully appreciate how serious a threat Perseus posed to them. With ample amounts of money and food with which feed his own people and pay his army for more than a decade, Perseus assumed a defensive stance and awaited a Roman attack.

Perhaps Perseus was aware of the limitations of his own army, even as its numbers continued to swell. At some point between the time of Alexander and Perseus, the Macedonian commanders had subordinated the cavalry to the infantry, putting all of their faith in the infantry phalanx. It has been suggested that this focus evolved from the fact that after Alexander’s death warfare in Macedonia remained a much more local affair, which meant battle in mountainous and uneven terrain unsuitable for cavalry. In theory, a phalanx of moving infantry could maneuver such ground more easily; but by Perseus’s day, the phalanx had developed a series of fatal flaws. The Macedonian phalanx was composed primarily of half-trained citizen-soldiers. Moreover, the spearmen were packed so tightly together that they could only move forward. Thus, the mobility that was typically associated with infantry had disappeared altogether. This meant that the phalanx was most effective on level ground. Since Macedonia was mostly mountainous, its troops would be in serious trouble defending their homeland.

For a moment, though, Perseus succeeded. The first Roman army ferried across the Adriatic Sea to face him was led by Consul Publius Licinius Crassus, who crossed to Epirus in the summer of 171 bc. Perseus soundly defeated Crassus’ army at Callinicus in Thessaly; afterward, Perseus indicated to the Romans that he wanted to enter into peace negotiations. This was extremely distasteful to the Romans, and they responded by demanding unconditional surrender.

As it happened, Perseus would get two more chances in 170 bc. Aulus Hostilius Mancinus was sent to replace Licinius, but he too was defeated by Perseus. The following year Quintus Marcius Philippus also proved wanting. Although he led the Roman forces deeper into Macedonian territory than his predecessor, he realized only too late that they were beyond the reach of their supply train. Perseus, though, did not know that the Roman army was overextended. He only knew that the Roman army was nearer to him than it had ever come before. He fell back on Pydna, a city on the Gulf of Thessalonica. Philippus was unable to follow, so Perseus repositioned his troops on the Elpeus River. Becoming increasingly dispirited, Philippus refused to attack the Macedonians. Perseus, who could have forced the Romans to fight, decided not to make the first move. The two armies remained in position on opposite sides of the river in a baffling stalemate.

The Roman Senate decided in 168 bc that Perseus could be dealt with properly only by a general and a consul who showed no interest in his own aggrandizement or the attainment of riches won from a protracted foreign campaign, or any of the other excuses thought up for Philippus and Licinius. The man chosen was Lucius Aemilius Paullus, whose father had fallen at Cannae and whose brother-in-law was Scipio Africanus, who defeated Hannibal at Zama. Indeed, by this time Paullus had already had an illustrious career himself in Spain and Liguria, and by 168 BC he was a sexagenarian.

As if making up for lost time, the Roman Senate not only agreed to Paullus’s suggestion that a committee be sent to Greece before any definitive plans were made, but also allowed Paullus to select its members. It only took two days for the three chosen men to set off. Upon returning, the ignorance of the Macedonian situation back in Rome was finally rectified. The forces of Perseus and Philippus were at a standoff on either side of the Elpeus River, both leaders either unable or unwilling to initiate a fight. Meanwhile, Appius Claudius’s Roman forces in Illyricum were running out of food and succumbing to apathy. It was immediately suggested that if both armies received renewed support and the vigor of leadership, Perseus and his men could be caught between these two forces.

Meanwhile, Perseus committed several foolhardy mistakes. In attempting to buy off Rome’s Gallic allies, Perseus refused to hand over the agreed amount up front, and it soon became clear to the Gauls that he was not going to pay them at all. The Gallic force, which was led by Clondicus, numbered 10,000 infantry and cavalry.

Perseus was a “better guardian of his money than his kingdom,” wrote Livy. When the Gauls gave up and withdrew north to the Danube, Perseus justified his decision by saying it was dangerous to allow so many Gauls into Macedonia anyway.

The Macedonian troops, which had pinned their hopes on the Gauls, clearly thought otherwise since the Gauls’ presence in Thessaly alone would have cut off the Roman army’s main food supply. Yet Perseus tried the same tactic with Gentius, the king of the Ardiaei in Illyricum, another Roman ally. He promised Gentius a large sum of money. Gentius seized two Roman envoys in the hopes of proving that he meant business. Perseus hoped that Gentius’s actions would provoke such a strong Roman response that his men would be forced into a war regardless of whether they received complete payment, which he refused to give them in advance. “It was as if Perseus’s every action was designed to preserve as much booty as possible for the Romans after his defeat,” Livy wrote.

Such was the news delivered to Paullus and the Senate. Paullus then immediately selected tribunes for the two legions under his command, numbering 14,000 Roman foot soldiers and 1,200 cavalry. Two more legions, totaling 10,000 foot soldiers and 400 cavalry, were called up to serve under Lucius Anicius Gallus and the other forces stationed in Illyricum. Before leaving with his army, Paullus gave a lengthy speech to the Senate, warning them against second guessing. “At dinner parties, there are men who can march the army into Macedonia, who know where the camps should be established, which places should be occupied by garrisons, when and by which pass Macedonia should be invaded,” Livy quoted Paullus as saying.

In the spring of 168 bc Paullus and his legions crossed the Adriatic at Brundisium and landed in Greece. Gallus’s two legions made their way north to Illyricum, and a month later the would-be traitor to Rome, Gentius, was seized. By that time, Paullus had reached the Roman forces on the Elpeus River. He quickly gained the affection of the men when he found them short of water. The army was situated at the foothills of Mount Olocrus, and Paullus rightly assumed that it contained a hidden source of water. He ordered the soldiers to dig wells closer to the shoreline and the effort proved successful.

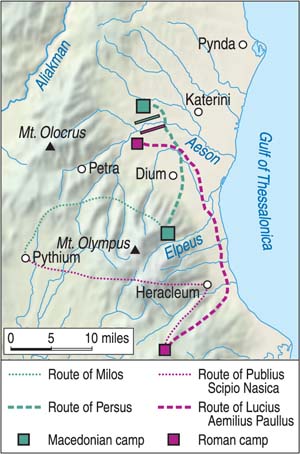

Taking stock of the situation with his officers, Paullus nixed the idea of a direct frontal assault on Perseus’s forces, which were heavily defended by catapults and ballistae. Instead, he chose to divert Perseus’s attention with a feint against his northernmost forces; at the same time he sent a large force around the mountains with instructions to fall on Perseus’s rear. He assigned two Perrhaebian merchants, who knew the mountain passes, as guides for approximately 1,000 men under the command of his son and Publius Scipio Nasica. Over the course of the next four days, and traveling only at night to avoid detection, they marched south along the coast of the Gulf of Thessalonica. When they reached the Tempe River they turned west and then north through the mountains toward Pythium and Petra. In the final leg, they angled east toward the gulf where they hoped to fall on Perseus’s camp. At the same time, more than 8,000 infantry and 300 cavalry arrived at the port of Heracleum in a diversion intended to deceive Perseus into believing that a large naval force was headed his way.

For the next few days, the plan worked. Paullus skirmished with Macedonian forces and then withdrew in the middle of the day, slowly drawing them more to the south and more vulnerable to attack from Nasica’s advancing army. As it happened, though, even Roman setbacks turned to their advantage. A short time after they set out, Cretan soldiers under Nasica’s command deserted and fled to the Macedonian camp. Perseus immediately sent a force immensely larger than Nasica’s 2,000 troops, but the Romans easily defeated them. Additionally, the Roman guides had been mistaken in assuming that many of the mountain passes were guarded. This not being the case, the way was open for Nasica and his men to descend downhill to strike Perseus’s camp. Afraid of being caught between Nasica and Paullus, Perseus fled north with his army. He marched his troops past Dium and established a new camp just south of Katerini. This placed his army 10 miles south of the town of Pydna.

In no time Nasica’s army, which was heading east, and Paullus’s army, which was advancing north, converged at Dium. While the former feared that Perseus would again slip away and suggested that they attack immediately, Paullus refused. Their men needed a rest, and he decided to set up camp only a mile or so away from Perseus’s forces with the Leucus River between them. The flat plain Perseus had chosen for his camp was suddenly neutralized as well, since even when fully rested the Romans were not about to cross the river onto such disadvantageous ground. The Roman camp, which was situated on the slope of Mount Olocrus, was equally unsuitable for the Macedonian army given that its phalanxes would not function well in that terrain. One of the armies might have to cross to unfavorable ground. It remained to be seen what matter of random and unforeseen circumstances would finally force it to do so.

A stalemate ensued, but there was no shortage of drama. The clash at Pydna can be dated precisely to June 22, 168 bc, because a lunar eclipse took place the previous evening. One of the Roman military tribunes, Gaius Sulpicius Galus, was aware of the event beforehand. He announced the event to a gathering of soldiers and advised his troops that no one should regard it as an omen. While Galus succeeded on this point, the soldiers still held his knowledge in awe.

While the Romans saw the eclipse as a good sign, the Macedonians regarded it as an evil omen. “The Macedonians regarded the eclipse as a bad omen, signaling the fall of their kingdom and the ruination of their people,” wrote Livy. “So did their prophets, and wailing and shouting filled the Macedonian camp until the light of the moon re-emerged.”

Still, both leaders were reluctant to enter battle the following morning. Even though he offered them a much needed rest, Paullus had been criticized by his men for not seeking battle immediately upon arriving on the scene, and he realized that, if given the chance, the standoff could end up no different than the one which had prompted his appointment in the first place. Meanwhile, Perseus had no desire to fight with a Roman army that was now well rested.

That morning detachments from both sides gathered drinking water from the Leucus River. Sent to retrieve the water for the Romans were two cohorts and some cavalry, and likely a similar complement of troops on the Macedonian side. While a truce had held as the troops gathered water, it is not surprising that such an arrangement did not last for long. At mid-afternoon a Roman mule broke loose and was chased by three soldiers into the water. Two Thracians in the Macedonian army led the animal over to their side, but the Romans killed one of them. Not long afterward the entire Macedonian army crossed the river.

The Romans, who had been itching for a fight, were more than happy to oblige. The noise of the initial skirmish alerted Paullus to what was going on. The fighting had progressed to such an extent that “it seemed neither easy nor safe to recall or stop the impetuosity of those who were rushing to arms,” wrote Plutarch. “Paullus thought it best to avail himself of the ardor of his soldiers, and to turn an accident into an opportunity.” Just as he began to lead his forces out for a proper battle, Nasica informed Paullus that Perseus was doing the same thing.

Paullus probably placed his two legions in the center with allied troops flanking them on the right and cavalry beside them on the left. His elephants were behind his troops. Giving in to the passion of his men, Perseus surrendered his advantageous position in the fields near his camp and crossed the Leucus River to the lower slopes of Mount Olocrus. His phalanxes initially forced back the experienced Roman infantry.

“First the Thracians advanced, whose appearance … was most terrible, men of lofty stature, clad in tunics which showed black beneath the white and gleaming armor of their shields and greaves, and tossing high on their right shoulders battle-axes with heavy iron heads,” wrote Plutarch. Following the Thracian division was a second division composed of mercenaries.

The third division consisted of “picked men, the flower of the Macedonians themselves for youthful strength and valor, gleaming with gilded armor and fresh scarlet coats,” wrote Plutarch. “As these took their places in line, they were illumined by the phalanx-lines of the bronze-shields which issued from the camp behind them and filled the plain with the gleam of iron and the flitter of bronze, the hills too, with the tumultuous shouts of their cheering.”

There is a sense from Livy’s fragmented account that Paullus suddenly found himself gripped by fear at the sight of the advancing Macedonians with their bristling spears. If this is the case, the astonishment and terror the spectacle initially presented was shared by the rest of the army. The lower slopes of Olocrus were defended by the Roman right line—that is, by their Italian allies and the Roman cavalry—and they were unsuccessful in beating back the Macedonians. Salvius, their commander, sought to inspire them by throwing their standard over to the enemy forces, but that had the opposite effect. Rather than inspire them, it served to demoralize them. The Roman line was driven back and gradually forced up the slopes of Olocrus.

The Macedonians must have felt their advantage swelling as they continued to push forward, and even the elephants the Romans introduced to the fight proved ineffective. But until this moment the Macedonian phalanx also had the advantage of fighting on relatively level ground. As the army began to ascend the Olocrus, this advantage dissipated and did so piecemeal. With whole sections of men advancing to different sections of the mountain, the Macedonian line began to peel back and break, and gaps opened up. “Either on account of the unevenness of the ground, or on account of the very length of the front,” wrote Livy, “those who attempted to occupy higher ground were necessarily, though unwillingly, separated from those who occupied lower positions.”

Plutarch describes how quickly and almost seamlessly Paullus perceived this development to turn it to the final advantage the Romans needed. “Dividing up his cohorts, Paullus ordered them to plunge quickly into the interstices and empty spaces in the enemy’s line and thus come to close quarters, not fighting a single battle against them all, but many separate and successive battles,” he wrote. “As soon as they got between the ranks of the enemy and separated them, they attacked some of them in the flank where their armor did not shield them, and cut off others by falling upon their rear, and the strength and general efficiency of the phalanx was lost when it was thus broken up.”

In the rough terrain, the Macedonian line became uneven, and the Romans were quick to exploit the situation by inserting units into the gaps that opened up before them. Sensing the day was lost, the Macedonian cavalry on the flanks quit the fight. “The cavalry left the battle virtually unscathed. Perseus himself led the flight,” wrote Livy.

Left to fend for themselves, the Macedonians were ripe for the slaughter. “The remaining Macedonian squadrons also rode off with their ranks intact since the infantry column lay in the path of the enemy; the killing of these men, which detained the victors, had made them forget to pursue the cavalry,” wrote Livy. “The slaughter of the phalanx, from the front, from the flanks, from the rear, went on for a long time.”

Those Macedonian foot soldiers who were able to escape the slaughter headed for the Gulf of Thessalonica. Once there, some drowned while others were cut down in the water by Roman troops in ships. In their desperation, the Macedonians had mistaken the ships for those of their allies. Some of the Macedonians turned inland only to be trampled by the Roman elephants. Even by the standards of warfare in the ancient world, the carnage was awful. Among the captives taken after the battle was the Greek historian Polybius, who would chronicle in his epic historical work how the Roman Republic advanced to the point that it dominated the Mediterranean region.

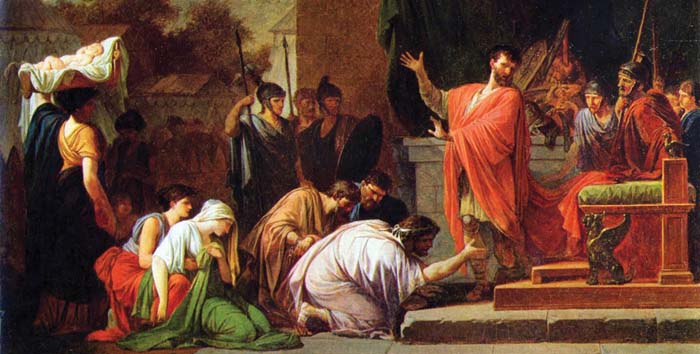

In the aftermath of the decisive defeat of the Macedonian army, Rome demanded the virtual impotence of their enemy, as well as its allies throughout the Aegean Sea. Macedonia ceased to exist and was divided into four separate leagues, with marriage and business alliances prohibited across boundaries. Its top officials and ruling class were shipped off to Rome, while show trials were held throughout Greece and many officials were executed. Illyricum and Epirus received the same treatment. Against his better judgment, Paullus allowed his men to plunder Epirus at will, enslaving thousands. Meanwhile, more than 1,000 members of the Achaean League, including Polybius and all of the Roman allies in the struggle, also were deported to Italy. Rome then imposed its rule on their lands.

Pydna made Rome into a world power. Whether this happened by choice or by chance, the Romans still embraced that status, or at least saw its maintenance as the only way of assuring their own survival. On the one hand, there is the belief that Rome became an empire reluctantly, and that without the succession of Punic and Macedonian wars, which forced the Roman Republic into the wider net of eastern Mediterranean politics and warfare, Rome may have remained satisfied without such expansion. On the other hand, many believe that the culture of Greece eventually defeated their conquerors, and that Hellenism won out in the end.

The famous sack of Corinth in 146 bc led to the wholesale deportation of Greek art and sculpture that would have a vast influence on Rome in the centuries that followed. This point is no better illustrated than by the fact that the victorious commander at Pydna, the Roman Consul Paullus, took Polybius into his household and entrusted him with the education of his children.