By Christopher Miskimon

World War I was only a few days old when the German light cruiser SMS Emden, patrolling off the Korean Peninsula, spotted its first target. Shortly after 4 am on August 4, 1914, lookouts spotted what they believed to be the Russian cruiser Askold. The Emden’s crew readied for action. The Russian vessel fled before it, prompting Emden’s crew to fire a series of warning shots. The vessel slowed after the tenth round and stopped after two more.

A boarding party from the Emden discovered that it had not overtaken the cruiser Askold, but instead the 3,500-ton Russian merchant vessel Ryazan. The vessel, which had 80 passengers, had no cargo aboard that would make it a valuable prize. But Captain Karl von Muller, the commander of the Emden, decided to bring the large, fast ship to the German naval base at Tsingtao, China, for conversion into an armed merchant cruiser.

The boarders took control of the vessel and ran up the German flag. The two ships arrived in China on August 6. By the end of the month Ryazan would leave port, renamed the Cormoran and under German control. It was the German Navy’s first prize of the war, and it marked the beginning of an amazing record for the Emden.

Although the U-boat is often seen as the star of the German Navy during the Great War, Kaiser Wilhelm II’s small force of ships scattered around the globe also gave good service. Some were warships built for specific purposes, and others were converted merchantmen. They had one thing in common, though. They all raided enemy shipping and tied up large numbers of Allied ships dedicated to hunting them. Of all Germany’s raiders, none had a career as bold as the Emden.

In the early 20th century Germany controlled a small overseas empire and found itself in growing competition with other European powers, chief among them the United Kingdom. The German East Asiatic Squadron was based at Tsingtao and represented the bulk of German naval strength in the Pacific. The force was commanded by Konteradmiral Maximillian von Spee and included a number of cruisers and smaller vessels along with auxiliary vessels to carry coal, which was the lifeblood of warships during this period. Coal gave ships a great advantage in speed and maneuverability, but their endurance was limited by what they could carry in their bunkers.

Among von Spee’s force was the Emden. The SMS that preceded the light cruiser’s name was the German acronym for “His Majesty’s Ship.” She was built in 1908 in Danzig on the Baltic Sea. Weighing in at 3,593 tons, Emden was 387 feet long with a beam of 43 feet. The cruiser was armed with 10 10.5cm cannons along with nine 5-pounders, four machine guns, and two torpedo tubes. Her steam engines provided 13,500 horsepower for a top speed of 24 knots. The 790 tons of coal she could carry gave her a range of 1,850 miles at 20 knots or 3,790 miles at 12 knots. Maximum armor thickness was four inches.

Korvettenkapitan Karl von Muller initially commanded the Emden. Born in 1873, he was the son of a Prussian Army officer. When the war began he had 23 years of service in the German Navy and was known as a quiet, competent officer who had the respect of his crew. His second in command was Kapitanleutnant Helmuth von Mucke, who was born in 1881 and also was the son of an Army officer. Mucke had served 14 years and was an extroverted officer who had the crew’s undying admiration. His skills complemented those of von Muller.

Emden had two other notable officers. The first was Leutnant zur See Franz Joseph, a nephew of Kaiser Wilhelm. He served as the ship’s torpedo officer. The other was Kapitanleutnant Julius Lauterbach, a reservist who had only recently joined the crew. Lauterbach had long plied the Indian and Western Pacific Oceans as an officer of the Hamburg-Amerika Line and had extensive knowledge of the region, the ships that serviced it, and the type of men who served as crew on those ships. Both von Mucke and Lauterbach would prove invaluable during Emden’s service as a commerce raider.

On the war’s eve Emden was in port at Tsingtao. In June the British cruiser Minotaur paid a visit. The Emden’s crew helped host the event, which included balls, banquets, and an athletic event. The Germans won at gymnastics and the high jump while the British crew triumphed in the soccer match. Sailors from both countries got along so well that upon the Minotaur’s departure there were numerous protestations that the two nations would surely never fight one another. In the months preceding the war, many of the crew rotated home with the arrival of new replacements. Having new crew to train kept the officers busy.

By the end of July 1914, war was imminent. Admiral von Spee was concerned about his ships becoming trapped at Tsingtao when war broke out. Japan was expected to join the Anglo-French alliance, and it had a substantial fleet nearby. To prevent the loss of his maneuver force von Spee took his fleet to sea on July 31 and soon after dispersed it. It was during this time Emden’s crew captured the Ryazan. After delivering that ship to Tsingtao for conversion to an armed merchant cruiser, Emden rejoined the fleet at Pagan in the Marianas Island chain on August 12.

The admiral commanded two armored cruisers, four light cruisers (one of which was the Emden), and a number of supply ships. The challenge became the pressing need for coal to keep the ships sailing. The admiral did not believe there would be a steady supply for his force in the Western Pacific Ocean, so he decided to sail for the Eastern Pacific Ocean. Admiral von Spee expected his ships could readily replenish their coal supplies in the ports of South America. What is more, his ships would find plenty of British merchant vessels in the Eastern Pacific to prey on.

Rather than leave the Western Pacific completely in Allied hands, von Spee decided to leave a single light cruiser, the Emden, behind to attack local shipping and other targets of opportunity. One supply ship, the Markomannia, would accompany the Emden. The Markomannia carried 6,000 tons of coal and would keep the cruiser going for some time. Eventually the ship would have to find new sources of fuel through captured ships or raids.

Emden and Markomannia sailed southwest from Pagan Island on August 14. Captain von Muller had the crew rig a fake funnel amidships. Emden had three stacks but adding a fourth would make her physically resemble a British County-class cruiser to any distant inspection. Camouflaging her appearance was not only a survival tactic for a commerce raider but also would help lull target vessels into a false sense of security when she approached. The crew had to maintain constant watchfulness and be prepared to act swiftly, whether to attack a merchantman or flee a superior warship.

Eight days after leaving Pagan, the two German ships slipped quietly through the Molucca Passage near Indonesia. They stopped where possible to take on water and provisions. On August 29 they moved into the Indian Ocean and entered the Bay of Bengal with its busy shipping lanes. Coal was running low and Emden needed to secure more before she was rendered adrift. Von Muller began hunting for ships as they approached Ceylon, and on the night of September 9 the crew spotted a light in the darkness. They quickly overtook a ship that turned out to be the Greek steamer Pontoporos.

Although Greece was a neutral nation, Lieutenant Lauterbach boarded the ship to check its credentials and manifest and found the ship was under contract to deliver coal to the British naval base at Bombay. This marked the cargo as legitimate contraband. The Germans even offered the Greek captain the chance

to sail with them under contract and the captain agreed. Von Muller integrated Pontoporos and its cargo of 6,500 tons of coal into his task force.

The Emden arrival in the Indian Ocean was unexpected by the Allies and this gave the ship free rein for a time. Von Muller did not waste this advantage and quickly began striking at the merchantmen in the region. On the morning of September 10 smoke was spotted and the cruiser gave chase. Lookouts spotted what appeared to be a merchantman but had strange white structures on its deck that were feared to be gun emplacements. Von Muller took a chance and they moved in, signaling the ship to stop and not use its radio. The boarding party discovered they had taken the British ship Indus, under contract to transport troops of the Indian Army. The white structures were merely newly constructed horse stalls. The ship also carried luxury goods that were quickly confiscated.

The ship’s streak of success continued into the next several months. In all Emden captured 23 vessels totaling 101,182 tons, which constituted an impressive record. Coal and other supplies were taken as necessary to keep the German ships going. Pontoporos was eventually sent off on other duties but Markomannia remained. Captain von Muller went to great lengths to treat captured crews with such civility as wartime allowed. Two of the ships he captured were used to take prisoners to neutral ports to be interned or exchanged. Even British newspapers heard of von Muller’s chivalry and wrote kind words about him, grudgingly admiring his success as well.

Despite the respect accorded von Muller and his ship, the Allies spared no effort to find the Emden. At its height, a total of 78 British, French, Russian, and Japanese warships were scouring the seas for the German cruiser. Telegraph and radio stations were advised to watch for the vessel and signal immediately if she appeared. Many of these stations were remote and could not hope for timely rescue, but at least it would give the hunters a last location to renew their search. It was imperative to stop the Emden. Shipping in the Indian Ocean was brought to a stop within a short time, insurance rates skyrocketed, and much needed troop convoys from Australia and New Zealand were delayed for lack of suitable escorts.

Along with its record of seizing enemy merchantmen, the Emden also conducted daring raids and attacks that only intensified the Allies efforts to end her cruise. On the evening of September 22, Emden cautiously approached the Indian city of Madras. No Indian coastal city had come under attack in centuries. The city was well lit with few precautions taken against attack from the sea. It was a calculated risk. Madras had powerful shore batteries that

were sure to reply. The main target was the Burma Oil Company’s storage facility with its oil tanks.

Just before 10 pm Emden sat a mere 3,000 meters offshore, her course designed so that errant shells would not strike civilian homes. Again, von Muller was showing his chivalry, though no doubt he also wished to avoid accusations of German barbarity. Minutes later the ship stopped engines, drifting into position at the port. The captain ordered the searchlights turned on and they lit the target ashore. Accompanying the order to illuminate the oil tanks was the command to fire. Emden starboard battery flashed to life, flames spilling from the muzzles of her cannon as explosive shells soared toward land. The first salvo went high, sailing over the oil tanks, though a few rounds found a shore battery. The second salvo landed short, near the water’s edge. The crew had bracketed their target, a good sign. The third salvo struck a tank, sending a cascade of black oil gushing forth as it ignited. Flames leapt into the sky, eliciting a hearty cheer from the German sailors.

The gunnery officer adjusted his aim. Another salvo crashed into the next tank, yet nothing happened because the tank was empty. The third tank was full, though, and it exploded, sending flames skyward. The shore batteries returned fire but scored no hits. Their mission accomplished, von Muller ordered a cease fire and Emden quickly withdrew. He kept his ship’s lights on as it headed north. Once out of sight, the lights were extinguished, and she changed course to the south. Approximately 5,000 tons of oil was destroyed, and the citizens of Madras were sent into a panic. Many of the panicked citizens fled the city. It was a daring raid that caused the British great consternation and increased the Emden’s reputation.

Just over a month later Emden struck again, this time against an enemy naval force. The Russian cruiser Zhemchug and four French torpedo boats were in port near Penang, Malaya. They were part of the force detailed to hunt for the German raider. The Zhemchug’s crew was cleaning her boilers. Three of the four French torpedo boats were unable to respond quickly because their boilers were cold; however, the fourth torpedo boat, Mousquet, was actively patrolling the area.

The Emden, which was disguised as a British light cruiser, sailed into the area without being challenged at 5:15 am on October 22. When it closed to within 500 meters of the Zhemchug, the Emden’s crew raised the German flag. The German cruiser fired a torpedo from 200 meters that struck the Russian cruiser’s engine room. The German sailors simultaneously raked the enemy ship’s crew quarters with their guns.

The Russian sailors fired a few rounds in response, but scored no hits. The Emden swung around for another pass. This time it put a second torpedo into the enemy cruiser, which detonated its magazines. The resulting explosion blanketed the area in smoke. In the one-sided surface engagement, the Zhemchug had suffered 91 killed and 106 wounded.

Emden stalked the harbor for other targets but soon Mousquet appeared on the horizon. Von Muller ordered an attack and cannon fire lashed out at the small French ship. At 4,000 meters one round struck one of Mousquet’s boilers, covering the ship in a fog of steam. In return, the French ship launched a torpedo and replied with a single gun. Within 10 minutes the battle was over, and the torpedo boat sank. Emden was chased briefly by two of the other torpedo boats but quickly made her escape. This successful raid further increased Emden reputation, especially after the Germans rescued 36 survivors.

The ship’s next target was the Cocos Islands, where the British maintained a cable station. Radio intercepts led the crew to believe no enemy ships were close enough to interfere. Unknown to them, one of the troop convoys was nearby, strongly escorted and under radio silence. By this time Emden consort was the coal ship Buresk, captured earlier near Ceylon. Buresk was sent away to await developments and Emden moved on Direction Island, home to the cable and radio station.

Arriving just after dawn on November 9, von Mucke led a 50-man landing party in three boats. Emden’s crew did not think they had been spotted, but a Chinese worker saw the ship and warned the British. The British challenged the ship and then sent out a message: “SOS Emden Here.” Von Muller had the transmission jammed, but it was too late. Both radio and telegraph distress calls were already out. In the mistaken belief that no help was nearby, the Germans proceeded with their plan.

The Allied troop convoy was 55 miles away. It received the SOS signal, and the commander sent the Australian cruiser HMAS Sydney to investigate. The ship was armed with eight 6-inch guns and was well armored. Moreover, she was faster than the Emden. At 9 am Sydney arrived near Direction Island, but the Germans initially mistook her for the Buresk. They realized their error 15 minutes later and quickly got underway, leaving the shore party behind. Unfortunately for von Muller, all 10 of his gunlayers, that is, the men who aimed the ship’s guns, were ashore. There was no time to retrieve them. At 9:40 am she opened fire on Sydney and despite the absence of the gunlayers her first salvo bracketed the Australian ship. Emden had to close the distance to make her guns more effective and use her torpedoes.

Sydney’s Captain John Glossop knew this and turned his ship to keep the distance open. Still, Emden’s third salvo struck, knocking out both of Sydney’s fire control stations. This slowed down the Australian’s fire and hindered accuracy, but her armor was shrugging off the German shells. Sydney’s first hit came 20 minutes later, destroying Emden’s radio room. Glossop kept turning his ship to increase the range, giving his 6-inch cannons the edge. An ad-hoc fire control station was set up and soon shells were pounding the Emden. First, the electrical system was knocked out. Then, the steering gear suffered extensive damage, thus reducing the vessel’s maneuverability. The fire from the Australian ship became more accurate as a result. Even worse, a shell landed among the aft guns and detonated their ammunition, killing the crew and causing a large fire.

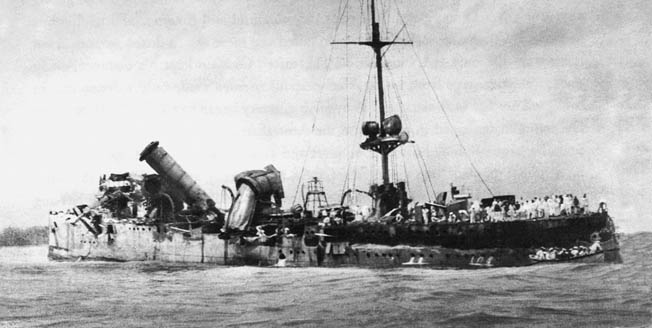

Shell after shell landed on the Emden, crumpling the upper decks and bringing down the foremast. The killing blow was a salvo that hit all three funnels, collapsing them. This denied air to the boilers, reducing the ship’s speed. Emden was defeated. Von Muller knew he had to quit the fight. Rather than abandon ship, he directed it to nearby North Keeling Island. He beached the Emden on the island’s reef. Sydney fired two more salvos before realizing the Emden was finished. At that point, the Australian ship went in pursuit of the Buresk, which appeared nearby. The crew of that ship scuttled and abandoned her.

Von Muller and his surviving crew became prisoners. German casualties numbered 134 sailors. The prisoners were generally treated well and many Allied officers personally visited the German officers to congratulate them on their valor and accomplishment, despite their status as enemies. Von Mucke and the landing party managed to sneak off in a schooner. They sailed across the Indian Ocean to Arabia. From there, they continued overland to Turkey, where they arrived in May 1915.

As for the Emden, she lay stuck on the reef where she had been ditched until the 1950s, when a Japanese salvage company removed what was left of the hull. The Emden’s career, which ended in what became known as the Battle of Cocos, was brief but brilliant. It was marked not only by its impressive prizes, but also by the humanity and chivalry of its crew.

Join The Conversation

Comments