By William F. Floyd, Jr.

At the start of the American Civil War in April 1861, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln proclaimed that he planned to blockade the Confederacy by stationing warships in waters off its shores. This entailed guarding 3,500 miles of coastline along the Atlantic seaboard and Gulf of Mexico. The primary targets of the blockade were the 12 largest ports.

The Confederate Navy endeavored to break the Union blockade, but it was seriously inferior to the vastly larger U.S. Navy. The Confederacy ruled out constructing a comparable fleet because of a shortage of funds. A partial answer to the blockade lay in the privateers’ use of steam-powered ships that could run the Union blockade. Yet the privateers met only a fraction of the Confederacy’s need in regard to getting sufficient exports of cotton to foreign markets and importing enough munitions and other war materials. The Union blockade quickly slowed the Confederacy’s exports and imports to a crawl.

Southern inventors sought to develop a weapon that could counter the blockade fleet. The Confederate government offered private contractors a bounty of 20 percent of the value of any warship sunk by a licensed privateer. Inventors put their minds to developing an underwater vessel that could attack the blockading ships.

The idea of submersibles was not a new one. Inventor David Bushnell had introduced the submarine Turtle during the Revolutionary War. The Turtle had conducted an unsuccessful attack in September 1776 against the British 64-gun Eagle anchored in New York Harbor. Most of the work related to submersibles during the late 18th century was theoretical rather than practical, though.

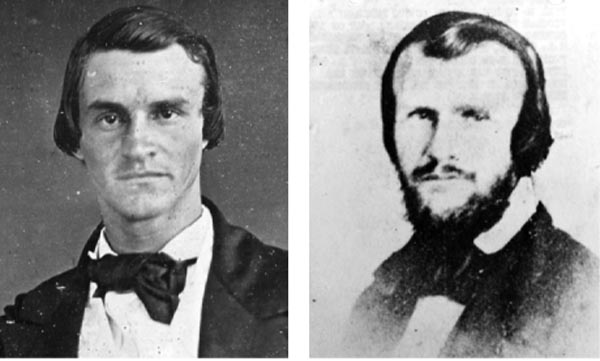

Three visionary naval engineers—Horace Hunley, James McClintock, and Baxter Watson—gathered in New Orleans in 1861 to build an underwater vessel that might serve as a much-needed nautical weapon against the Union blockade. The U.S. Navy also was at work on a submersible to use against Confederate ships. In November 1861 the U.S. Navy entered into a contract with French inventor Brutus de Villeroi, who lived in Philadelphia, to develop a hand-cranked, screw-propeller submarine. The U.S. Navy ultimately purchased the vessel, named the Alligator, when it was completed in June 1862. It met a swift demise when it sank in rough seas in April 1863.

Horace Lawson Hunley was the most influential and resourceful of the trio of Southern inventors. A native of Tennesee, he attended the University of Lousiana. He went on to study law and was admitted to the bar in 1849. Hunley amassed considerable wealth as a sugar and cotton planter in Lafourche Parish during the 1850s. In 1857 he was appointed to serve as a clerk in the U.S. Customs House in New Orleans. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Hunley was a special collector for the Port of New Orleans, which made him an agent of the Confederate government.

The three inventors built a prototype submarine they named the Pioneer. In February 1862, they tested the vessel in the muddy waters of the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain. But the Union advance on New Orleans the following month prompted the men to scuttle the Pioneer in the New Basin Canal on April 25, 1862.

The men resumed their work in Mobile, Alabama, where they teamed up with Thomas Park and Thomas Lyons to develop a second vessel, the American Diver. The design team received substantial assistance from the Confederate Army. Lieutenant William Alexander of the 21st Alabama Infantry Regiment stepped in to oversee the work. In the course of its construction, the marine engineers experimented with electromagnetic and steam propulsion before deciding on a simple hand-cranked propulsion system. The American Diver underwent trials in Mobile Bay in January 1863. The trials revealed that its propulsion system was too slow to be practical. An attack by the American Diver on Union vessels the following month was unsuccessful. The submarine sank in Mobile Bay during a storm and was never recovered.

After the loss of the American Diver, work began on a new vessel known as the H.L. Hunley. The third vessel was primarily Hunley’s project. He constructed his crude, hand-powered submarine from a 25-foot-long cylinder boiler that was 48 inches in diameter. He cut the boiler in half lengthwise and installed two half-inch iron straps on each side.

Next, Hunley extended the structure by fitting it with a tapering iron section both fore and aft that extended it to 40 feet in length. The resulting underwater vessel was four feet wide and five feet deep. He then installed water tanks outfitted with a stop-cock, an externally operated valve, that permitted water to flow into a tank to submerge the vessel. He also installed a pump to empty the tanks for raising the boat. To assist the pilot in determining the depth, Hunley installed a mercury gauge. He also installed a shaft, controlled by a lever amidships, to raise or lower the fins.

The submarine was outfitted with a hatchway fore and aft. The hatches were sealed with rubber gaskets and bolted from the inside. Each of the vessel’s hatches had an eight-inch-high combing. Glass was installed in the sides and ends of the combings to allow the crew to see outside of the vessel. The designers made an opening in the top of the boat for a lever-operated air box outfitted with another stop-cock to admit air. Because of its long, slim shape it was dubbed the “Fish Boat.”

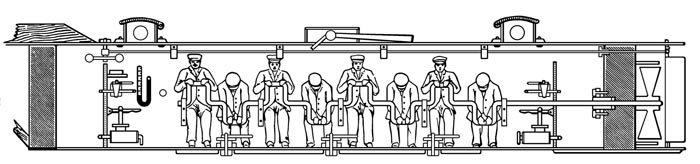

The Hunley was operated manually by a commander and eight crew members. The commander navigated the vessel by looking through glass viewing ports in the hatch cover. He controlled the submarine’s depth with a handle that operated the dive planes, and he steered the Hunley with a lever that operated rods and cables that turned the vessel’s rudder. The eight crew members operated the hand-cranked propeller shaft. The propeller revolved inside a wrought-iron ring to guard against it being fouled. The shaft and cranks took up much of the space inside the vessel, making movement next to impossible. Besides being cramped, the vessel was also dark. The only light came from a candle the commander used to read the depth gauge. The crew could operate the Hunley underwater, but the vessel required calm seas to run successfully.

The Hunley’s armament originally consisted of a floating explosive charge that used a contact fuse attached to the end of a 200-foot-long rope. The intent was to have the Hunley dive under its intended target and then surface once it had passed by it. The vessel would pull the torpedo against an enemy ship to make it explode.

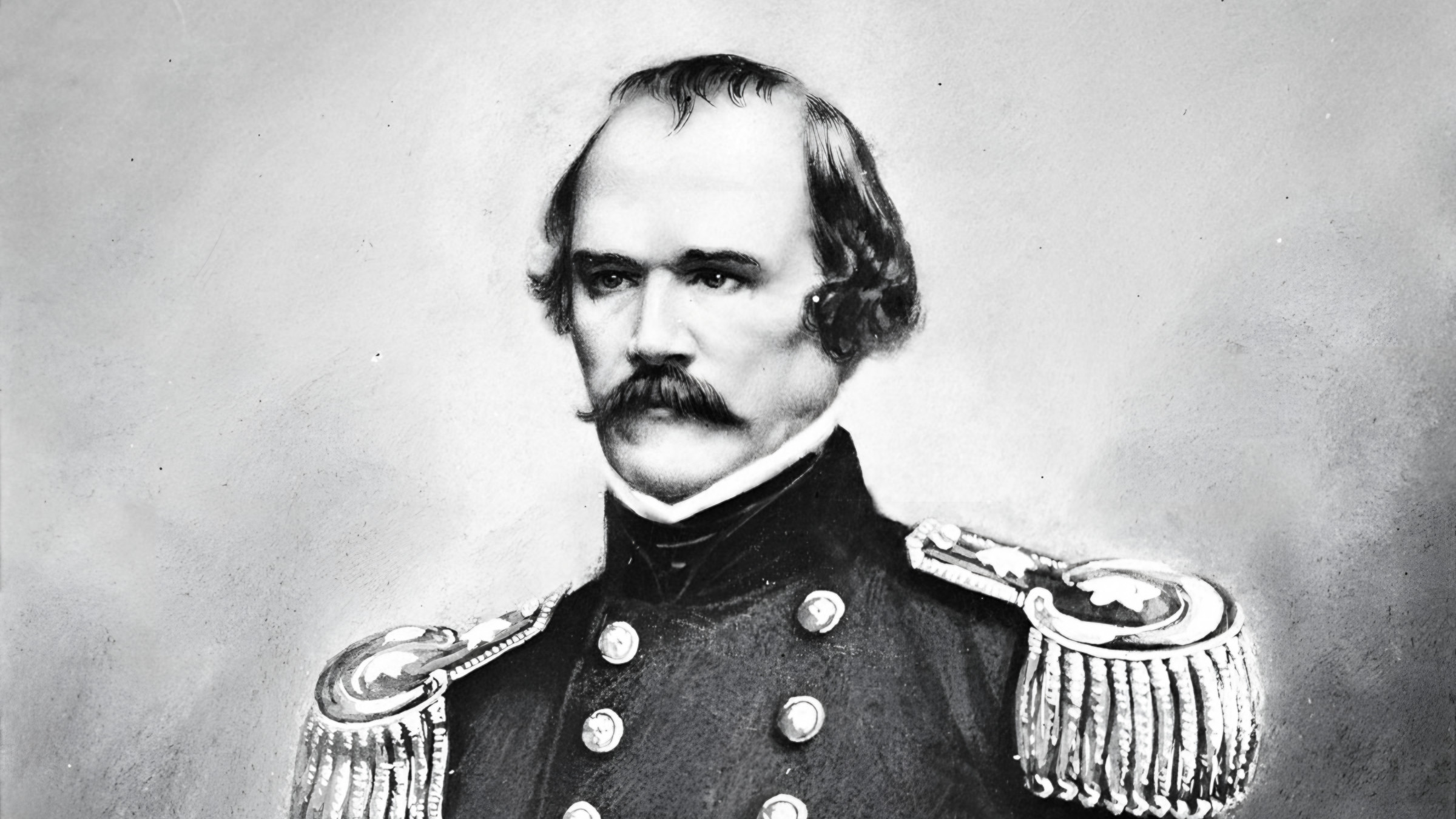

The first trial with the newly constructed submarine took place with mixed results in Mobile Bay in July 1863. The Hunley submerged well enough but could not return to the surface. Nevertheless, the underwater vessel received the support it needed to go into action from Admiral Franklin Buchanan, the Confederate naval commander in Mobile and former commander of the CSS Virginia. In response to inquiries by General P.G.T. Beauregard, the commander of Charleston, South Carolina, Buchanan sent him a written endorsement in which he praised the Hunley’s potential.

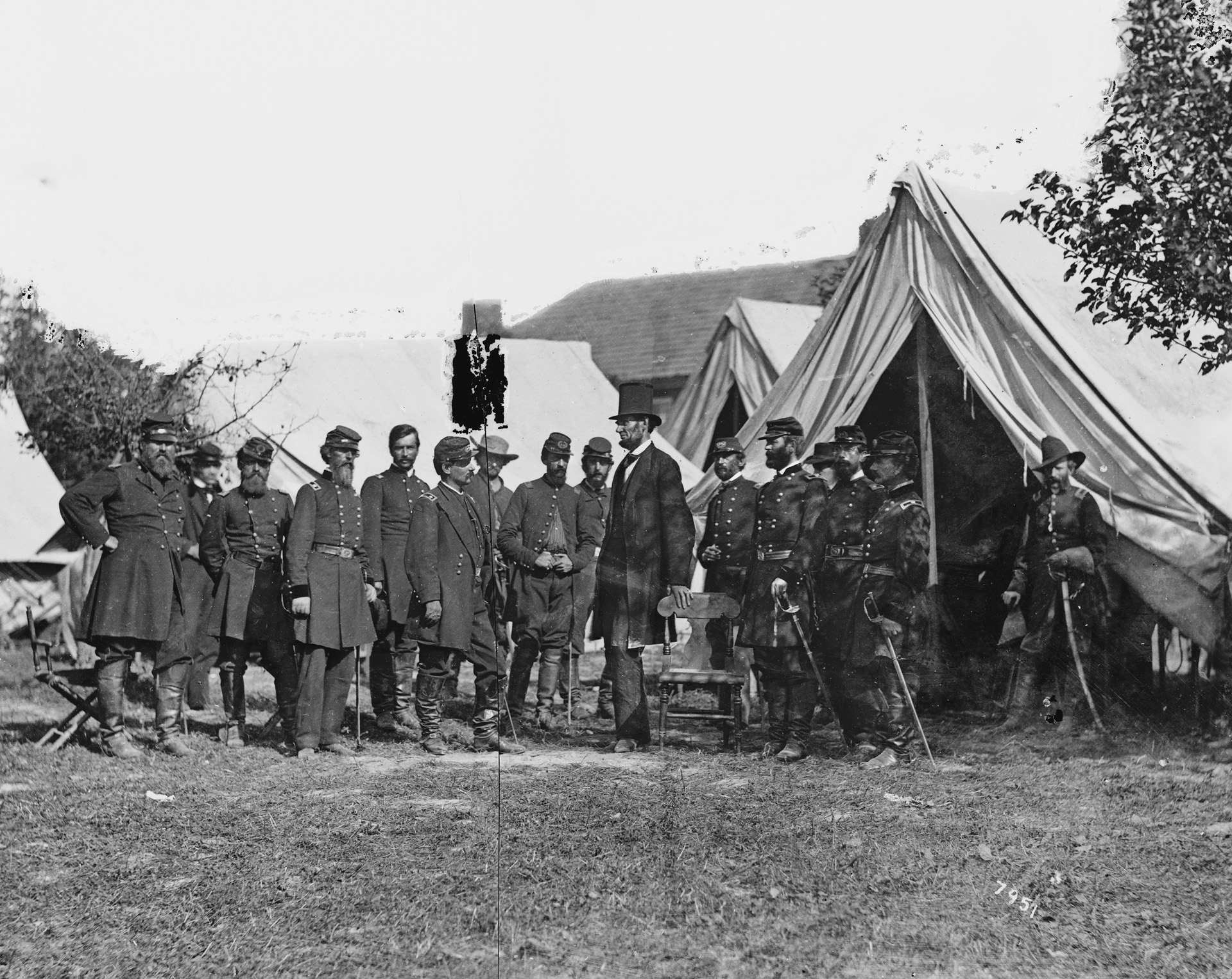

Beauregard subsequently arranged for the Hunley to be shipped by rail to Charleston. The Hunley arrived on flatcars on August 12. Inventor-turned-captain James McClintock, the first commander of the Hunley during its Charleston deployment, was reluctant to engage the Union ships. Beauregard quickly grew impatient with McClintock’s timidity. Beauregard decided that the only way to get the vessel into action was if Confederate military forces owned it. He therefore convinced the Confederate government in Richmond, Virginia, to acquire the vessel. By late August, McClintock had been sacked. He was replaced by Lieutenant John Payne, who took charge of the vessel’s volunteer civilian crew.

The Hunley was plagued throughout its development with problems associated with its submerging capabilities. While the boat was tied to the wharf at Fort Johnson on James Island, a passing steamer swamped it, sending it to the bottom. The men aboard the vessel at the time perished. Payne escaped because he was able to get out of a hatch. As soon as the vessel was raised, Payne and another crew volunteered for service. When the boat set out on a trial run, Payne became tangled in the Hunley’s internal equipment and inadvertently made the vessel dive while the hatch covers were open. Water swept into the vessel as the crew tried desperately to evacuate. Although Payne, Lieutenant Charles Hasker, and two crewmembers escaped, the rest of the crew drowned. Hasker, who was not ordinarily assigned to the vessel, had joined it for the test. While Payne and the other two men managed to swim free before the vessel hit the sea floor, Hasker miraculously managed to free himself after going to the bottom of the harbor.

The vessel was successfully raised from the harbor floor and cleaned for another trial; however, by that time the Hunley had a reputation as a death trap. Because of that, it was difficult to find more volunteers. When Horace Hunley learned of the continuing fatal accidents, he was convinced that the crews were improperly operating the vessel. He journeyed to Charleston to instruct the next crew in the proper operation of the underwater vessel. Beauregard was heartened by Hunley’s willingness to personally train the new crew.

Another sea trial took place on October 15, 1863. The inventor was aboard the vessel to ensure its proper operation. This time the vessel was scheduled to make a practice dive underneath a stationary Confederate receiving ship, the Indian Chief, anchored in Charleston Harbor. Although it successfully submerged, it failed to return to the surface. Hunley and the crew members all perished in the botched trial. The eight crew members, as well as Hunley, were laid to rest in a plot called “Hunley Circle” in Magnolia Cemetery in Charleston. The Hunley’s run of bad luck earned it the nickname “floating coffin.”

At that point, Beauregard was ready to scrap the program, but Lieutenant George E. Dixon, who was knowledgeable in the operation of the Hunley, convinced Beauregard to allow him to continue the trials. During the next trial, a cable to which the contact explosive was attached became entangled in the rudder of a ship towing the Hunley.

To remedy the entanglement problem, the vessel was outfitted with an alternate torpedo system. A spar torpedo was installed to be used when the submarine was six or more feet below the water’s surface. The explosive system consisted of a copper cylinder packed with 90 pounds of black powder attached to a 20-foot-long wooden spar mounted on the bow. The crew would ram its barbed tip into the target. Once the torpedo was affixed to the enemy ship, the crew would back away to a safe distance. Then the crew would activate the torpedo with a mechanical trigger. At this point, the Hunley was moored at the Battery Marshall dock on Sullivan’s Island.

The Confederates were finally ready to use the Hunley against a ship in Charleston Harbor. The Union fleet, though, had learned from deserters and spies that an effort was going to be made to destroy one or more of its vessels using a submersible. Although the Union ironclads that were stationed closest to shore took precautions to prevent a torpedo attack, wooden vessels that were farther out in the harbor took no such precaution in the mistaken belief that they would not be targeted. Dixon decided to attack one of the wooden ships.

During the interim period before the attack, the Hunley underwent more sea trials. During one of the trials, the vessel was successfully submerged for two hours and 35 minutes. Lieutenant Dixon and his crew waited for the optimal conditions to carry out their attack. They got their opportunity for a completely flat sea on the cold and windless night of February 17, 1864. The vessel departed from Breach Inlet, a passage noted for its strong current. Within 300 yards of his target, Dixon brought the Hunley to the surface to make one last observation.

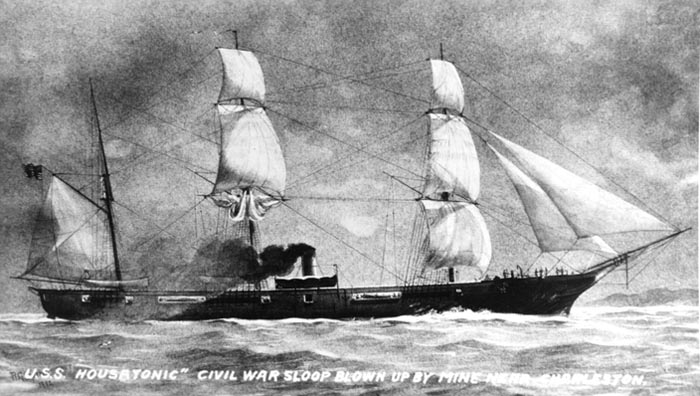

Dixon had singled out the USS Housatonic, which had been on station for nearly a year and a half. The 207-foot-long, steam-powered, propeller-driven Union sloop of war mounted 12 cannons. Captain Charles Pickering, the commander of the ship, had orders to keep a sharp eye out for blockade runners. For that reason, he had the vessel’s fires stoked so that she could make steam on a moment’s notice.

As the Hunley approached the Housatonic, Dixon paused the vessel long enough to take in fresh air through the open hatchway and confirm his bearings. He then gave the order for the Hunley to proceed on its mission.

At 8:45 pm acting Master John K. Crosby on the deck of the Housatonic spied something in the chilly, dark waters of the harbor. After initially believing he had seen a porpoise, Crosby decided instead that it might be a Confederate torpedo boat. He sounded the alarm. Since the mysterious vessel was directly beneath the towering, three-masted sloop, the Union cannoneers could not depress their guns far enough to fire on it. Instead, the Union sailors began firing on the vessel with muskets and shotguns in a futile attempt to stop it. The bullets ricocheted off of the Hunley’s armor. The crew rammed the barb of the spar torpedo into the Union ship’s hull. The torpedo struck the Housatonic’s starboard side near its powder magazine. The crew of the Hunley then reversed the propeller as fast as they could crank the shaft.

The muffled explosion tore a hole in the Union ship. A geyser of water erupted into the air alongside the Housatonic, and then water began pouring in through the breach. Just three minutes had passed between the time the submarine had been sighted and the point at which the torpedo detonated. The Housatonic took on water quickly and slowly began to sink. Those who were able scrambled into hastily launched lifeboats, while the remainder climbed the rigging toward the starry sky. Since the vessel was in just 27 feet of water, the top of the rigging stayed above the surface of the water as the ship settled on the bottom. The USS Canandaigua dispatched rescue boats to pluck the men from the rigging and take them to safety. Because of these factors, the Union loss of lives was greatly minimized. Only five Union sailors perished in the ordeal. The Hunley never returned to the wharf on Sullivan’s Island; it went to the bottom, taking its crew with it.

In the final analysis, the Hunley killed far more of her own crew members than enemy sailors. Despite its tragic sea trials, the Hunley played a crucial part in the development of underwater warfare vessels. The Hunley has the distinction of being the first American submarine to sink an enemy warship in battle.

Efforts to find the Hunley began immediately after it sank. Union sailors dragged the waters around the Housatonic, hoping to find the Confederate submarine. It was believed for more than a century that when the Housatonic was scrapped the submarine was inadvertently demolished along with it. But evidence existed to contradict this assumption. Survivors of the Housatonic testified to the U.S. Navy in 1894 that after the explosion occurred light signals were exchanged between Confederates on the shore and a vessel in the water. This was confirmed by a Confederate officer who stated that he had answered a signal from the Hunley on its return from its mission.

The Hunley was eventually located seaward, not landward, of the Housatonic. Its location was unknown for 131 years because those searching for it had been looking between the Housatonic and the shoreline. The searchers assumed the submarine had gone to the bottom while attempting to return to shore. Of course, the reason it was seaward is unknown.

The salvage team found a softball-sized hole in the Hunley’s forward conning tower, which led some experts to speculate that small arms fire from the sailors on the Housatonic shattered cast iron, allowing water to flood the Hunley. Other experts speculate that the crew ran out of air and succumbed to anoxia.

A private organization, the National Underwater and Marine Agency, spent 15 years trying to find the Hunley. Using a magnetometer, members of the organization finally located a large metal object in 1995 four miles off the coast of Sullivan’s Island. The vessel was located in 30 feet of water obscured by three feet of sediment. The salvagers raised the Hunley on August 8, 2000. It is now exhibited in the Warren Lasch Conservation Center in North Charleston, South Carolina. It is on display in a specially designed tank that holds 90,000 gallons of fresh water necessary to preserve it.