By Victor Kamenir

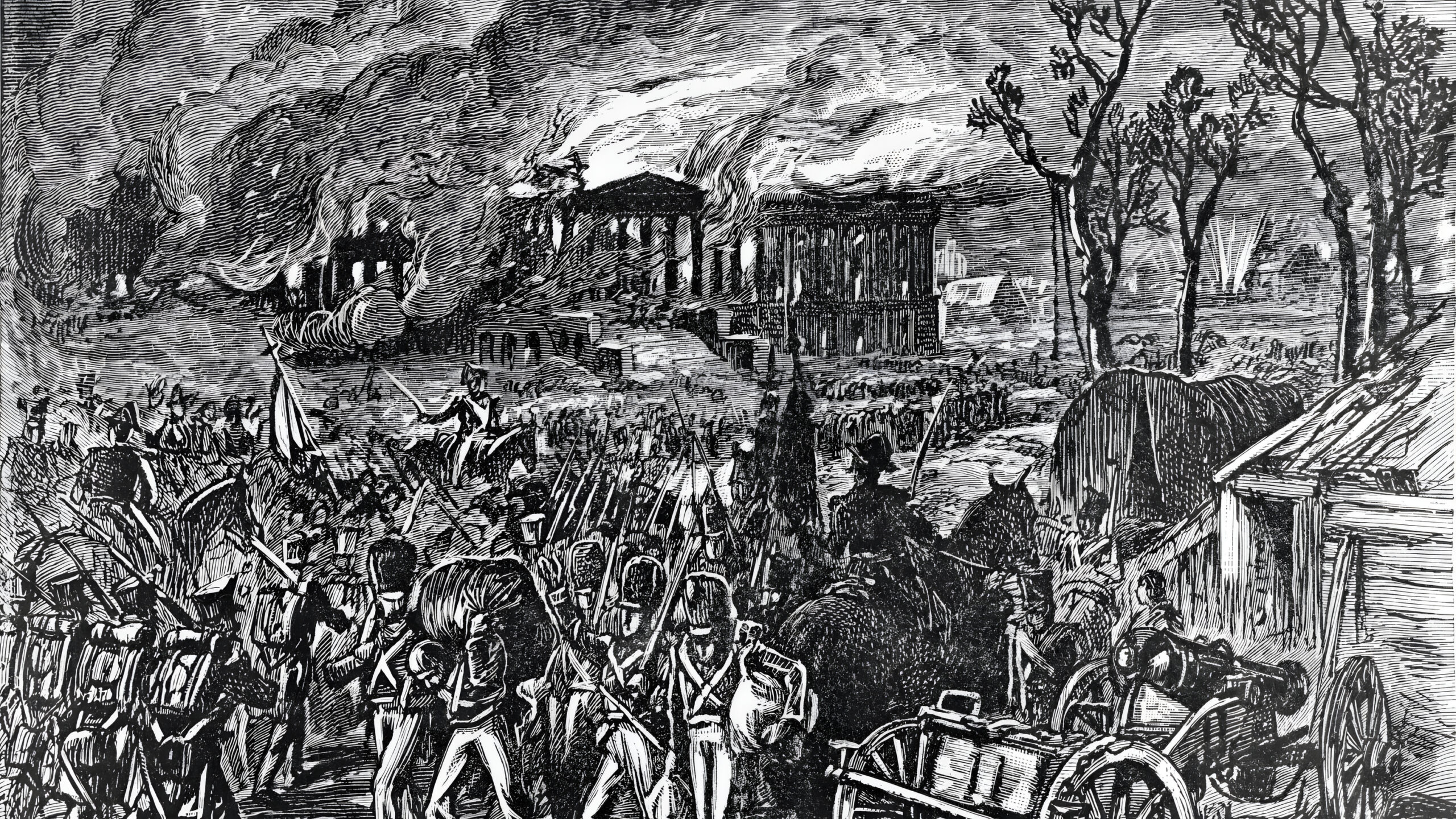

The troops of Germany’s Army Group Center were more than a week into a fresh offensive to capture Moscow on July 14 when they approached the historic battlefield of Borodino where the Russians delayed Napoleon’s advance on Moscow in 1812. Dug in on the battlefield were the forward elements of a fresh division from the Soviet Union’s Far East Military District that had been rushed to Moscow to thwart the German drive on the Soviet capital.

The burly men, outfitted in fur caps, great coats, and fur boots, belonged to Colonel Viktor Polosukhin’s 32nd Siberian Rifle Division, which had arrived from Vladivostok by rail and reached the old battlefield several days earlier. As soon as they arrived, they entrenched and constructed emplacements for their artillery. Stalin had reinforced the division’s three rifle regiments—the 17th, 113th, and 322nd —with two armored brigades equipped with T-34 and KV-1 tanks.

Approaching their position were elements of General Erich Hoepner’s Panzer Group 4. Hoepner had tasked Lt. Gen. Friedrich Kirchner, commander of the 10th Panzer Division, with the destruction of the troops in and around Borodino. Kirchner assigned some of his best units for the hard fighting that lay ahead.

The tactical plan called for Colonel Bruno Witter von Hauenschild to lead his infantry brigade and the SS Reich Motorized Infantry Division in a frontal assault while the 7th Panzer Regiment moved to outflank the Siberians. The attacking armor and infantry were supported by Stuka dive bombers, 88mm flak guns, and Nebelwerfer rocket launchers.

As the battle unfolded, T-34 medium tanks counterattacked in mass formations. The Germans put their powerful 88mm flak guns to work as tank busters. Soviet artillery units and mortar batteries blasted the German grenadiers as they fought their way forward through minefields and barbed wire.

The slugfest at Borodino lasted for nearly a week before threats from the flanks forced the Soviets to retreat. The 32nd Rifle Division was mauled by the Germans, although it inflicted grievous losses on the attacking German units; for example, the Third Infantry Regiment of the SS Reich Motorized Infantry Division suffered such heavy losses that it had to be disbanded and its survivors distributed to other regiments in the division. Nevertheless, the Germans pushed on to the next Soviet line of defense, the Mozhaisk Line. Stalin believed that the 17th Rifle Regiment in particular had fought with great valor, and he therefore awarded it the Order of the Red Banner.

On June 22, 1941, the Germans had invaded the Soviet Union in a surprise attack involving 3.6 million German and other Axis troops organized into 153 divisions. Hitler and his generals had organized the attacking troops into three army groups for the invasion, which was codenamed Operation Barbarossa. Field Marshal Wilhelm von Leeb’s Army Group North was ordered to push toward Leningrad, Field Marshal Fedor Von Bock’s Army Group Center was tasked with capturing Moscow, and Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt’s Army Group South was sent into the Ukraine to secure the Donets Basin. The Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH), the German Army High Command, believed that the Red Army could be defeated west of the Dvina-Dnieper line, but it had not developed contingency plans if that did not occur as expected.

Despite suffering devastating losses early in the campaign, the Red Army did not collapse. It was able to hold itself together through the grim determination and draconian measures instituted by the ruling Communist party. The German timetable for a lightning-fast campaign to occupy all of the European Soviet Union within four months slowly began to unravel. Although German panzer formations continued their push eastward, infantry divisions fell far behind, not only because they lacked mechanized transport, but also because they had to methodically eliminate large pockets of Red Army troops.

Army Group Center became embroiled in a two-month-long slugfest known as the Battle of Smolensk in July. The battle raged over a swath of territory that was 400 miles long and 150 miles deep. It began on July 10 when General Heinz Guderian’s Panzer Group 2 and General Herman Hoth’s Panzer Group 3 advanced from Vitebsk toward Dukhovschina and Orsha toward Yelnya. Their objective was to encircle the Soviet 16th, 19th, and 20th Armies. During the titanic clash, the Germans were startled by the effectiveness the Soviet of T-34 medium tank and KV-1 heavy tank, Katyusha rocket launcher, and IL2 Sturmovik ground attack aircraft. These weapons platforms awed the Germans and they had no choice but to acknowledge that the Soviets had made impressive strides in military technology.

The T-34 medium tank was superior to any tanks the Germans had in action at the time. The T-34 outclassed the German Army’s Panzer IV in many respects, including speed, armament, and armor. Its 76mm long gun was more effective than the Panzer IVs short-barreled 75mm gun. The two Soviet tanks had sloping hull and turret armor that enabled them to withstand all but the heaviest German antitank guns. Last but not least, both the T-34 and KV-1 had wide treads that gave them better traction on mud and snow than the German tanks.

Hitler and the generals of his personal staff in the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW) clashed sharply with the OKH generals in regard to how Barbarossa should proceed. The two highest ranking generals of the OKH were Field Marshal Walter von Brauchitsch, commander in chief of the Army, and General Franz Halder, chief of OKH general staff. They led a faction that believed that the capture of Moscow would destroy the Red Army’s morale and quickly win the war. They were supported in this belief by Field Marshal Fedor von Bock, the commander of Army Group Center, and his hard-charging panzer generals Guderian and Hoth. As for Hitler, he had long favored the destruction of the Soviet field armies over capture of key objectives such as Moscow. Thus, Barbarossa had been a compromise of sorts between the opposing viewpoints.

But after nearly two months of hard fighting in which Army Group North and Army Group South had encountered difficulties, Hitler for all intents and purposes postponed the drive on Moscow by Army Group Center to reinforce the other two army groups. He ordered Hoth’s panzers to reinforce Army Group North and Guderian’s panzers to reinforce Army Group South. Valuable time was lost while Guderian assisted in the destruction of the General Mikhail Kirponos’ Southwestern Front in the month-long Battle of Kiev that began in late August.

In early September, while the Battle of Kiev was still raging, Hitler believed that success on the northern and southern flanks had made a concerted push in the center imperative to bring about the total collapse of the Soviet resistance. Furthermore, he wanted to secure the economic resources of the Ukraine and shore up the flanks of Army Group Center.

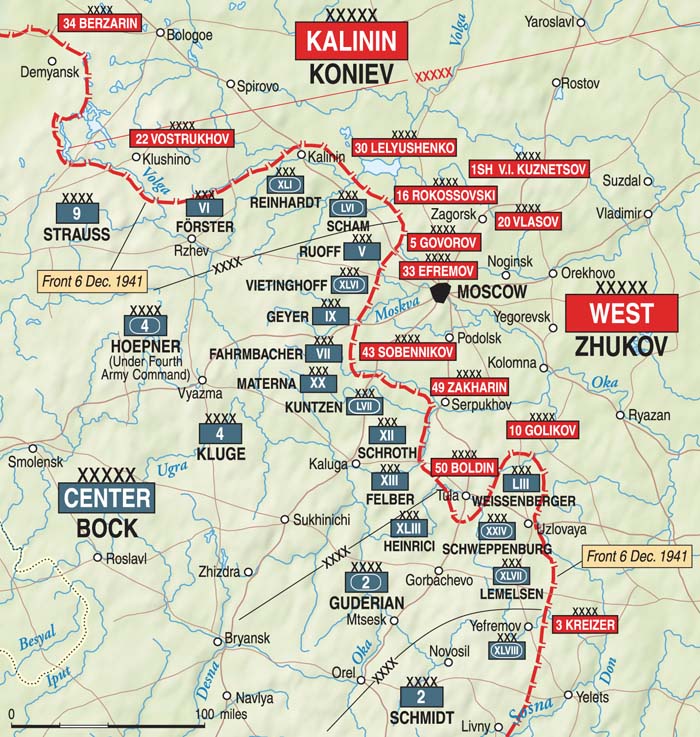

Führer Directive 35, which was issued September 6, set forth that the successes on Barbarossa’s flanks had made it possible to resume the advance in the center against Marshal Semyon Timoshenko’s Western Front. Timoshenko’s front “must be destroyed decisively before the onset of winter,” the directive stated. With this in mind, von Bock and his staff developed a plan for the final push on Moscow, codenamed Operation Typhoon. In the initial stage of the operation, Panzer Groups 2, 3, and 4 were to surround and destroy the bulk of the Red Army forces facing Army Group Center in and around Vyazma and Bryansk. Next, the panzer groups would swing north and south of Moscow and link up at Noginsk, 20 miles east of the Soviet capital. The northern pincer, composed of the Hoth’s Panzer Group 3 and General Erich Hoepner’s Panzer Group 4, would strike at Moscow from the northwest through the city of Kalinin, while the southern pincer, Panzer Group 2, was to advance on Moscow from the southwest through Tula. Meanwhile, General Gunther von Kluge’s 4th Field Army would advance directly toward Moscow from the west.

German forces for Operation Typhoon numbered approximately two million men, 1,700 tanks and assault guns, 14,000 artillery pieces and mortars, and 780 aircraft. Despite seemingly large numbers overall, German units began showing signs of fatigue. Attrition of men and matériel exceeded expectations and replacements did not keep pace with casualties. This situation was especially serious in motorized formations, where loss of tanks and tracked and wheeled transport seriously affected the combat efficiency of the panzer divisions.

Despite the attrition, morale was high and German troops were confident of victory. “The last decisive battle of this year will deliver a destructive blow to the enemy,” exhorted Hitler. “We will remove the threat to the German Reich and all of Europe, which has existed since the time of the Huns and the Mongols, of an invasion of the continent.”

Deployed east of Smolensk, Army Group Center was opposed by Lt. Gen. Ivan Konev’s Western Front, Marshal Semyon Budyonny’s Reserve Front, and Lt. Gen. Andrey Yeremenko’s Bryansk Front. The armies that made up the three Soviet fronts were exhausted from the sustained heavy fighting. Their effective strength at the time was 1,250 men, 1,000 tanks, and 7,600 artillery guns.

The Russians used rivers as defensive positions, especially the Desna River in the area of operation of the Bryansk Front; however, Soviet defenses lacked deployment in depth, continuous defensive lines, and sufficient antitank artillery. Soviet formations, especially those of the Western and Bryansk Fronts, were brittle after tremendous losses sustained during the summer fighting. To assist the hard-pressed fronts facing Army Group Center, Stavka concentrated reserves and equipment on the most threatened directions, particularly along the two highways leading to Moscow from the west.

Having the farthest distance to travel, Guderian’s Panzer Group 2, which was deployed on Army Group Center’s southern flank, was given a lead of three days over the other panzer groups. Guderian had some of the best units in the German Army. He had at his disposal five panzer divisions, four motorized infantry divisions, and the Grossdeutschland Motorized Infantry Regiment. Despite attrition, he still had 300 tanks.

Guderian’s panzer units began their advance on September 30 against Yeremenko’s Bryansk Front. They caught Maj. Gen. Arkady Erm-akov’s Operational Group by surprise. When he reported the German attack to Yeremenko, he was instructed to counterattack. He sent his 30 light tanks against Kampfgruppe Eberbach of the 4th Panzer Division on October 1 only to see them turned into flaming hulks. Once through the porous Soviet defenses in this sector, the XXIV Panzer Corps reached Orel on October 3, while the XLVII Panzer Corps captured Bryansk on October 6.

The rest of Army Group Center attacked on October 2. On Guderian’s left, despite strong artillery and air support, the 2nd Field Army stalled in front of forward Soviet defenses along the Desna River in the face of determined Red Army opposition. Despite this, the 4th Field Army and Panzer Group 4 conducted a successful crossing of the Desna River and penetrated Soviet defensive positions up to 20 miles in several locations. In a similar manner, the 9th Field Army and Panzer Group 3, which were positioned on the left flank of Army Group Center, achieved substantial success and reached the Dnieper River on October 3.

Stavka’s orders to the Bryansk Front to form a new defensive line came too late to save it from destruction. The capture of Bryansk by the XLVII Panzer Corps trapped three armies of the Bryansk Front in two pockets. The 50th Army became trapped in the Bryansk pocket north of the city, and the 3rd and 13th Armies were surrounded in the Trubchevsk pocket south of the city.

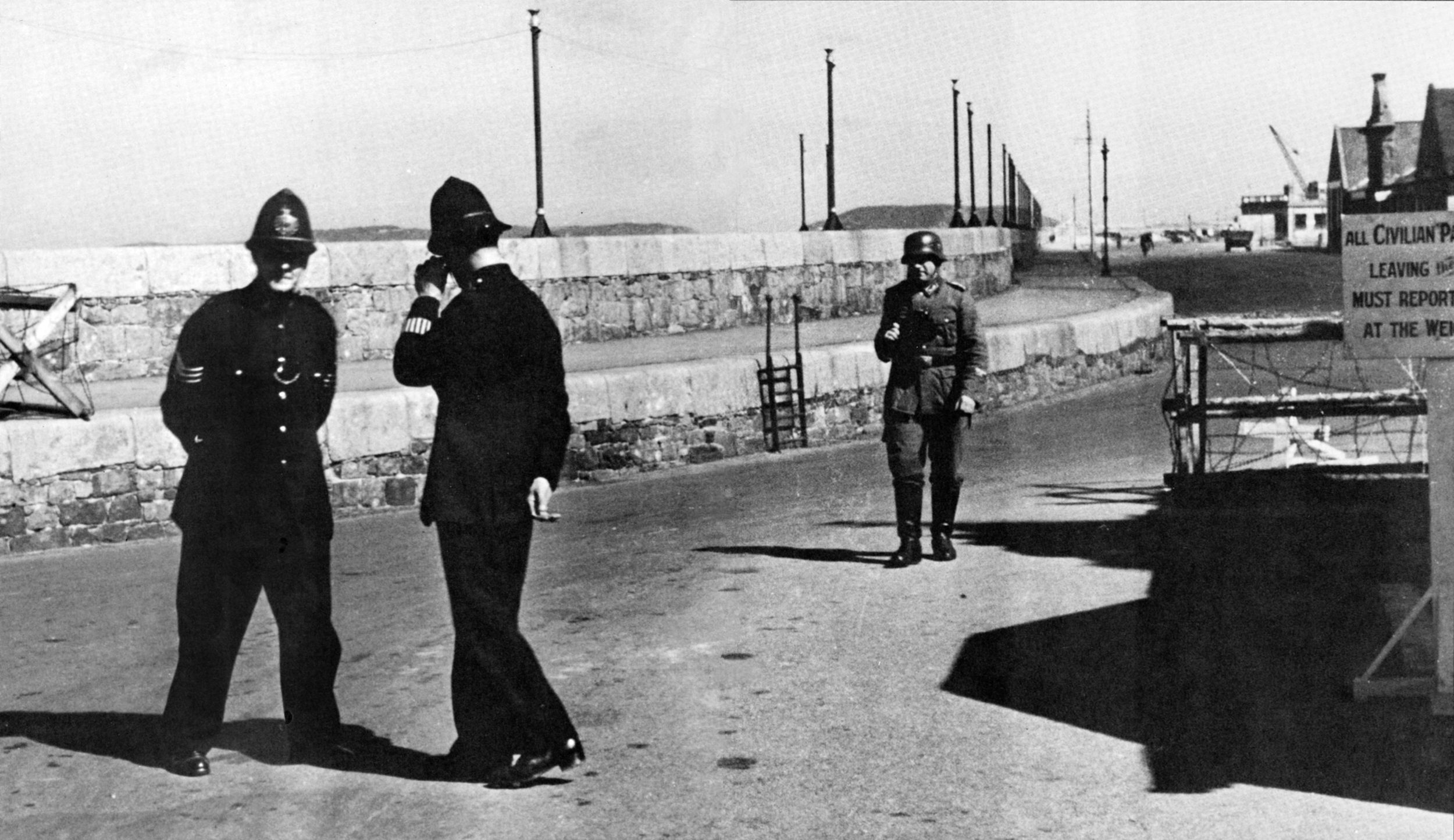

Soviet fighters guard the skies above Moscow. German air strikes against the city began on July 22 and continued for four months.

Similarly, the 2nd and 10th Panzer Divisions from Hoepner’s Panzer Group 4 closed the pincers east of Vyazma on October 10, thus trapping four armies of the Western and Reserve Fronts (19th, 20th, 24th, and 32nd) in a giant cauldron west of the city.

The outer encirclement rings initially were composed of German mobile formations that lacked the manpower to seal off all avenues of escape. The Soviet troops trapped in the pocket made repeated attempts to break out to the east. But as German infantry divisions moved up, the noose tightened around the Red Army troops and Luftwaffe aircraft unmercifully pounded their positions.

Some of the Red Army troops, their units astonishingly cohesive despite the constant shelling and bombing they endured, were able to escape their respective pockets during the following two weeks. They were reorganized and put in new defensive lines farther east. By the middle of October, the units still inside the Bryansk and Vyazma pockets began surrendering en masse. Although 85,000 soldiers escaped encirclement, the German Army captured 680,000 Soviet soldiers.

Even as the fighting continued in the Vyazma and Bryansk pockets, the first snow fell on October 7. The resulting snowmelt turned the Russian roads, most of which were unpaved, into a quagmire of mud. As a result, the German supply system slowed to a crawl. Heavy rains began a week later, heralding the arrival of the Rasputitsa (literally meaning time without roads) season in which travel on roads was extremely difficult because of muddy conditions. Rasputitsa, which occurs throughout Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine in the spring and fall, results from poor drainage of underlying clay-laden soils.

The Rasputitsa robbed the Germans of their mobility, which was one of their key advantages over Soviet forces. Vehicles broke down repeatedly or sunk to their axles in the sticky mud. Teams of men were commonly required to push and pull trucks and horse-drawn wagons out of the mud. Although Soviet forces also fell victim to the mud season, they had shorter supply lines than the Germans.

With the collapse of Soviet forward defenses, Stavka issued orders on October 9 for the creation of a new defensive line centered on the city of Mozhaisk, just 80 miles from Moscow. As survivors of Western, Reserve, and Bryansk Fronts trickled back, they reformed along the new defensive line. Western and Reserve Front units that had been mauled in combat were combined into the Western Front under the command of General Georgy Zhukov.

The Mozhaisk defensive line stretched for 180 miles in a shallow curve from the Ivankovo Reservoir on the Volga River north of Moscow to the city of Kaluga in the south. Zhukov, who was acutely aware that the 90,000 men under his command were woefully inadequate to create continuous defenses, concentrated his forces to defend main arterial roads leading to Moscow.

Even before pockets at Bryansk and Vyazma were eliminated, the Germans resumed the offensive toward Moscow. As they advanced, they exploited gaps in the Soviet defenses. The exhausted Red Army units gave way, and the Mozhaisk defensive line collapsed within a week. On the northern flank, Major Josef Eckinger’s advanced detachment of the Lt. Gen. Friedrich Kirchner’s 1st Panzer Division captured Kalinin on October 14, in the process cutting the Leningrad-Moscow railway and capturing an intact bridge over the upper Volga. This put the Germans in that area just 93 miles from Moscow.

To defend Moscow from the north, three right-flank divisions of the Western Front were reorganized into a new Kalinin Front under Lt. Gen. Ivan Konev. In the center, the Russian cities of Maloyaroslavets, Mozhaisk, Naro-Fominsk, and Volokolamsk all fell in quick succession to the Germans. By the end of October, German forces stood within 50 miles of Moscow.

As the Germans pressed ever closer, the Soviet State Defense Committee issued orders on October 15 for the evacuation of governmental, cultural, and industrial institutions, as well as foreign embassies, from Moscow. The next day, wholesale departure from the capital began to the east. The evacuation and resulting panic became known as Bol’shoi Drap (Big Bug-Out). For three days beginning on October 16 all semblance of order in Moscow collapsed. Factories, stores, and civil administration stopped working. Buses and street cars did not run. Officials at all levels attempted to use their positions to secure transport for themselves and their families out of the city. At some factories, management attempted to pay the workers before shutting down, while at others, officials fled with the money. Some food stores attempted to distribute the food on hand, while others were stormed and looted by the panicked populace. The Russians looted the warehouses, and criminals robbed and committed various atrocities with impunity.

Civil order broke down entirely as Moscow residents assaulted public officials who they believed had forsaken them. Train stations were thrown into chaos as crowds stormed the trains to secure a seat. Roads to the east became clogged with streams of trucks, cars, buses, and horse-drawn wagons surrounded by people fleeing on foot. In just a few days, the population of Moscow had been reduced almost by half.

When governmental institutions were evacuated, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin and a handful of advisers assisted by skeleton staffs remained at their posts. The Soviet government on October 19 began reasserting order by draconian measures. Police and military patrols appeared on the streets in force. Captured looters and bandits were shot on the spot and within three days order was restored in the Soviet capital.

While lawlessness in Moscow was brought under control, the situation at the front became critical. On October 20 the State Defense Committee declared that Moscow was under siege. Three concentric defensive positions with extensive earthworks were established around the city. Stavka put Zhukov in charge of the outer perimeter and placed Lt. Gen. Pavel Artemyev, commander of Moscow’s garrison, in charge of the city defenses.

The first defensive ring was an outer perimeter, the second defensive ring ran along Moscow’s suburbs, and the third defensive ring was in the heart of downtown Moscow. Approximately 100,000 civilians from Moscow and its vicinity, three-quarters of whom were women, furiously labored mainly with picks and shovels to erect antitank obstacles and dig antitank ditches. Inside the city, the garrison and the workers’ militia were tapped to defend an array of defenses that included barricades, antitank ditches, and gun emplacements. Unbeknown to the civilians, the majority of strategic objectives in Moscow were mined for demolition. Steps were taken to deal with every possible contingency; for example, resistance cells were organized to continue the struggle should the city fall to the Germans.

The Soviets created a formidable air defense system for Moscow consisting of one aviation and one air-defense corps. The 6th Fighter Corps numbered 600 aircraft, almost half of which were fighters. The 1st Air Defense Corps was armed with 1,000 antiaircraft guns and 300 quad machine guns. The defenders placed antiaircraft guns and machine guns on the roofs of Moscow’s buildings. To pinpoint the German aircraft they used hundreds of searchlights, and to thwart flights over the city they launched barrage balloons. German aviators, many of whom were veterans of the London Blitz, said that they had never encountered as dense a curtain of antiaircraft fire as they did over Moscow.

The Germans had made their first major aerial bombardment of Moscow on July 22, 1941. In that bombing mission, 220 Luftwaffe aircraft had attacked in four waves over a period of five hours. Although Soviet air defenses took a heavy toll on German aircraft, air raids on Moscow steadily escalated, peaking in November of that year. The bombing continued steadily until June 1943. In total, the Germans destroyed 6,000 buildings and killed an estimated 2,000 civilians.

On October 26, delayed by bad weather and fuel shortages, leading elements of the 2nd Panzer Army arrived before the city of Tula, the traditional center of the Soviet Union’s armaments industry. Survivors of Soviet 50th Army, after breaking out of the Bryansk pocket, conducted a fighting retreat to Tula, where the army was reorganized and reinforced.

A large militia regiment formed from the city’s workers took an active part in the city’s defense. Shifting the majority of the available fuel and ammunition to his leading XXIV Panzer Corps, Guderian launched repeated attacks against the city. Although the Germans reached the outskirts of Tula, they got no farther. While the fighting raged, Tula’s factories worked around the clock producing ammunition and repairing vehicles. Unable to capture Tula, Guderian was forced to swing east in an attempt to reach Moscow on a parallel route through Kashira. By this time, the German advance had ground to a halt as a result of exhaustion and heavy attrition. Indeed, many of the German divisions were down to one-third of their men and equipment. OKH ordered a halt to offensive operations on October 31.

Stalin’s determination and willingness to defend Moscow at all costs had paid off. A month earlier, on the same day that Guderian kicked-off Operation Typhoon, a conference took place in Moscow between Soviet, American, and British representatives. The United States had been providing economic assistance to the United Kingdom in its struggle against Hitler since January 1941. Stalin requested similar American and British assistance. U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt agreed on October 30 to extend to the $1 billion in interest-free loans to the Soviet Union for purchases of armaments and raw materials. The Russians already were receiving equipment, such as Matilda and Valentine tanks and Hawker Hurricane fighter aircraft, from the British government. It’s worth noting, though, that the British and Americans did not give the Russians their best equipment.

To stiffen the resolve of the Red Army and the Soviet people, Stalin ordered the traditional military parade held on November 7 in Red Square in Moscow. Several of his advisers recommended canceling the parade, but Stalin insisted. Many commanders expressed concern that the German bombers would stage a massive attack to disrupt the parade and kill the Soviet leadership. To guard against this threat, the Soviet Air Force began preemptive strikes against German forward airfields two days before the scheduled parade. The weather also cooperated, for low clouds and heavy snow were forecast for the event, thus reducing the concern of military officials.

The Moscow garrison, as well as units moving through the city to the battlefront, marched past Stalin and other senior leaders of the Soviet Union where they stood atop Lenin’s mausoleum on November 7. The show of determination was a great success. It demonstrated to the world the strengths of the Soviet people and their intentions to continue the fight against the invaders.

During the first week of December, frost formed on the roads in the Moscow region. The frozen ground enabled German units to move not only on the roads, but also through the countryside.

Up to that point, sporadic fighting had occurred on the Moscow front as both sides reinforced their positions. Compared to the situation in October, the Red Army’s condition improved significantly. Defensive positions of the three Soviet fronts stretched for 700 miles. Lt. Gen. Ivan Konev’s Kalinin Front held the right flank, Marshal Georgy Zhukov’s Western Front held the center, and Timoshenko’s Southwestern Front held the left. Stavka had dissolved the Bryansk Front and distributed its units between the Western and Southwestern Fronts.

As for Moscow, it was protected by artillery and engineer units positioned astride strategic roads into the city. Soldiers and civilians alike stoically braced for the German attack. Not content with static defense, Stalin constantly demanded that the Red Army units attack. Zhukov attempted to convince Stalin that the forces under his command were barely adequate for defense let alone attack; however, there was no persuading Stalin.

Zhukov, therefore, reluctantly ordered Lt. Gen. Konstantin Rokossovsky’s 16th Army to attack on October 16. Rokossovsky’s three depleted divisions were reinforced by the fresh 316th Rifle Division under Maj. Gen. Ivan Panfilov and the 1st Guards Tank Brigade under Colonel Mikhail Katukov. A task force consisting of Rokossovsky’s two rifle divisions, Katukov’s tank brigade, and two cavalry divisions under Maj. Gen. Lev Dovator were to retake the town of Volokolamsk on the Moscow highway.

While Rokossovsky was preparing his forces, Army Group Center renewed its offensive on November 15. Its objective was Klin, which was situated northwest of Moscow. The spearhead of Panzer Group 4 was General Rudolf Veiel’s 2nd Panzer Division, a relatively fresh unit. The division was outfitted with Panzer IIs, Panzer 38ts, and Panzer IIIs. It also had a small number of Panzer IVs.

The main thrust of the German offensive fell on Panfilov’s 316th Rifle Division, which was the strongest division in Rokossovsky’s command. Arriving from Siberia in August, the division spent most of the time in the reserve and was involved in active fighting only since October. Panfilov’s division was bled dry after five days of fighting, having lost four-fifths of its personnel. Although they had inflicted heavy losses on the Russians, the Germans were able to make only minor inroads into the Soviet defenses. In many instances, they advanced less than two miles a day. The 2nd Panzer Division was not able to achieve its objective of capturing Klin by October 20. Nevertheless, the 7th Panzer Division of Panzer Group 3 captured the town three days later.

The situation was so dire that Stalin called Zhukov and demanded an honest answer as to whether Moscow could be saved. Zhukov replied that it could, but reserves needed to be deployed immediately. Stalin transferred three armies from the reserves, the 1st Shock Army under Lt. Gen. Vasili Kuznetsov, 10th Army under Maj. Gen. Mikhail Yefremov, and 20th Army under Maj. Gen. Andrei Vlasov to Zhukov’s Western Front. Two armies, the 24th and 60th, were deployed to defend the city.

On November 27 Major Hans Freiherr von Funck’s 7th Panzer Division seized a bridgehead on the Moscow-Volga Canal, the last natural terrain obstacle on the way to Moscow. Its leading elements stood within 20 miles Moscow’s downtown, but the German offensive power was spent. A determined counterattack by the reserve 1st Shock and 20th Armies drove the Germans back.

Soviet combat engineers blew up six dams north of Moscow to hamper German progress. The resulting flooding inundated the surrounding low-lying terrain. A wall of water up to eight feet high and 30 miles wide flooded some villages, drowning residents who had not been warned because of the desire not to jeopardize security.

In the south Guderian renewed the offensive on November 18 by attempting to bypass Tula toward Kashira; however, the exhausted Germans were making slow progress, at times barely five miles a day, in the face of constant Soviet counterattacks. By November 27 Guderian’s offensive petered out and the threat to Moscow from the south was permanently eliminated. “The troops were no longer strong enough to capture Moscow and I therefore decided with a heavy heart, on the evening of December 5, to break off our fruitless attack and withdraw to a previously selected and relatively short line which I hope I shall be able to hold with what is left of my forces,” Guderian wrote about the situation.

Having encountered strong resistance north and south of Moscow, Army Group Center launched a frontal attack on Moscow with the 4th Field Army on December 1. The Germans fought their way east along the Smolensk-Moscow highway. The German attack, supported by a small number of tanks, ran into well-prepared positions of the Soviet 1st Guards Motor Rifle Divisions. Counterattacked in the flanks and unable to break through frontally, the German offensive stalled. On December 2 the 1st Shock and 20th Armies began steadily pushing back the Germans. The 20th Army in particular achieved such success at the village of Krasnaya Polyana, its commander, Lt. Gen. Andrey Vlasov, became known as the Savior of Moscow among the Russian troops.

At the tip of the German advance was the 638th Infantry Regiment, a unit composed of French volunteers and Russian emigrants. Unlike the Frenchmen led by Napoleon during his invasion in 1812, the men of the Legion of French Volunteers against Bolshevism did not reach Moscow, coming only within 20 miles of the Kremlin.

Lacking proper winter clothing, German troops suffered severely as the temperatures plummeted. Since German war planners had intended to defeat the Soviet Union by wintertime, the Wehrmacht had only manufactured enough winter clothing to supply those divisions that were to remain in Russia on occupation duty.

In some German units the losses from sickness and frostbite exceeded those from combat. To further exacerbate the plight of German frontline soldiers, the delivery of warm clothing was pilfered by the rear-echelon troops and only a small amount reached the front lines. To make up the shortfall, German soldiers turned to looting warm clothing from the Russian population. Freezing German soldiers near the front lines expelled Russian civilians from their homes.

Taking advantage of the German vulnerability, the Soviets parachuted saboteurs and commandos behind enemy lines with orders to burn homes and barns that the Germans used for shelter from the freezing temperatures. Their efforts frequently doomed their own citizens to a cold death as well. There were instances when local residents, in an effort to protect their homes, would capture the arsonists and turn them over to the Germans.

The Soviet high command ordered a massive counteroffensive in early December in an effort to relieve pressure on Moscow. Although German intelligence knew of the Red Army reserves staging to the east of Moscow, the strength of the Soviet attack shocked the Germans.

As early as September, Stavka had been steadily shifting the bulk of its divisions from the Far East Military District to the Moscow theater. Red Army divisions from Siberia, fully mobilized and held in readiness since June, formed the majority of Soviet strategic reserves. The front-ine forces of the Kalinin, Western, and Southwestern Fronts, combined with 58 divisions of the strategic reserves, numbered 1.1 million men, slightly more than the Germans facing them.

The units of the Kalinin Front switched to the offensive on December 5. They were followed the next day by units of the Western and Southwestern Fronts. At the start of the counterattack, the majority of fresh reserve divisions were distributed among the armies of the Western Front. This meant that the Kalinin and Southwestern Fronts had to carry on understrength and exhausted during the December fighting.

After several days of heavy positional fighting, Soviet forces began to penetrate German positions up to 10 miles in some places. Quickly committing reserves to exploit even the minor breakthroughs, the Red Army maintained pressure against both the flanks and rear of those German units still defending their positions. Two cavalry corps and one mounted mechanized group were sent to exploit the gaps and conduct raids behind German lines. Faced with a slowly crumbling front line, the Germans slowly began to fall back to avoid encirclement.

Faced with alarming reports, on December 8 Hitler reluctantly signed Directive No. 39, ordering the Wehrmacht to go on the defensive along the whole front. In some places German commanders pulled back to eliminate bulges in the front line. The shortening of lines occasionally resulted in the creation of reserves. On December 14 Halder and Gunther von Kluge, the commander of the 4th Field Army, gave permission for a limited withdrawal west of the Oka River without first seeking Hitler’s approval. When Hitler learned of this he was irate. He rescinded the order six days later, reminding his generals that they were to defend every inch of hard-won ground.

Enraged with the failure of Operation Typhoon, Hitler needed scapegoats and began a wholesale dismissal of senior commanders. On December 19, Hitler dismissed von Brauchitsch for health reasons and assumed the supreme command himself. Brauchitsch, whose health actually was declining since he had suffered a heart attack in November, was removed to the officer reserve where he remained inactive for the duration of the war.

By the end of December, dozens of generals were relieved of duty. One of these officers was Guderian, who languished in the officer reserve until 1943. For retreating without orders, General Erich Hoepner, commander of Panzer Group 4, was cashiered in January 1942.

The retreating Germans fought fiercely and the Red Army had to fight its way through the German defenses. Despite its battlefield losses, Army Group Center remained a potent and dangerous battle force. Indeed, Soviet casualties mounted to the point when the Moscow counteroffensive ground to a halt in the first week of January 1942.

Historians still debate the losses sustained by the opposing sides during Operation Typhoon and the Soviet counteroffensive. The start of the Battle of Moscow is commonly considered to be September 30, 1941. But there are still debates about the date of the end of the giant battle. Western sources typically consider the first week of January 1942 as the end of the Battle of Moscow; in contrast, many Russian sources include the Rzhev operation that followed, which began on January 8, 1942, and ended on March 3, 1942, as part of the battle. Soviet casualties numbered 658,279 for the defensive phase and an additional 370,955 until the end of the counteroffensive on January 7, 1942. In addition, the Soviets lost 4,000 tanks and 1,000 aircraft. During the same period, German casualties amounted to 460,000 men as well as 600 tanks and 800 aircraft.

By the end of the Soviet counteroffensive, the Red Army had advanced up to 150 miles in some places. The whole of the Moscow and Tula regions, as well as large parts of Kalinin and the Smolensk regions, were cleared of Germans and the threat to the capital was permanently eliminated. But the Red Army was not able to defeat Army Group Center. If it had been able to do so, the war on the Eastern Front might have ended in 1942. Believing they had captured the strategic initiative, the Soviet leadership launched several ill-prepared offensives in the first half of 1942. Although suffering tremendous losses that year, the Soviet Union was by that time fully engaged in the war of attrition, a contest that Germany could not possibly win.