By John E. Spindler

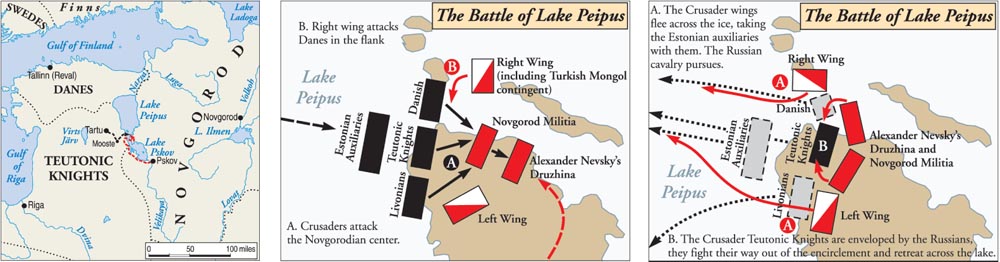

The mass of heavily armored crusader knights swept across the frozen surface of Lake Peipus toward the Novgorodian troops that waited anxiously on the eastern shore. As they drew close, Russian foot archers stationed in the center fired thick flights of arrows at them. A large group of horse archers stationed on the Novgorodian right wing rode into position to enfilade the crusaders’ left flank with arrows from their deadly composite bows.

A sound similar to a long roll of thunder occurred as the mounted crusaders crashed into the ranks of the Novgorodian army. Screams of rage and agony mingled with the steady clanging of steel as Teutonic, Livonian, and Danish knights swung their heavy broadswords in a frenzy of killing. Soon the slippery ice on which the crusaders fought was covered in blood and gore. Those crusaders who penetrated the Novgorodian line soon found themselves surrounded.

The sanguinary clash at Lake Peipus on April 5, 1242, on the Novgorodian-Estonian frontier was an attempt by the Teutonic Order to expand into the Principality of Novgorod and convert Orthodox Russians to Catholicism. It was an outgrowth of the so-called Northern Crusades whereby the Catholic Church supported military orders in their attempts to convert the pagan peoples of the eastern Baltic region to Christianity.

The spread of Christianity into this region had stalled in part because of the extreme environment in which these pagan peoples existed. They lived in a cold climate among broad marshes and dense tracts of forest that were laced with lakes and rivers. Despite the inaccessibility of the region, Christian Danes and Germans routinely traded by sea into the Eastern Baltic as far north as the Gulf of Finland. In the course of these commercial ventures, they established trading posts and settlements.

In the 1190s Popes Celestine III and Innocent III called on the German Catholic princes for aid in defending the Church of Rome’s new seat among the Livonians on the lower section of the Drina River. Pope Innocent had the hubris to demand at beginning of the 13th century that Orthodox Novgorod accept the Latin creed.

One powerful individual in particular responded enthusiastically to the Papal call. Albert of Buxhoeveden, a cleric who hailed from a wealthy family that dwelled in Lower Saxony, sailed from Lubeck to the site of a small community in Livonia established by merchants of the mercantile confederation known as the Hanseatic League.

Albert founded Riga in 1201 at which time he took the title of Bishop of Riga. The following year he established the Livonian Brethren of the Sword, or Sword Brethren, to protect German colonists in the eastern Baltic from attack by the pagans living in the region. In 1204 Pope Innocent III gave his official approval to the Sword Brethren. The newly founded military order advanced north into Estonia in search of land and riches. They relied on enormous cargo-bearing cogs operated by the Hanseatic League to supply them regularly in their far-flung outposts.

Albert’s brother, cleric Hermann Von Buxhoeven, also was involved in the Northern Crusades. His involvement in Livonia deepened in 1224 when the Sword Brethren conquered the city of Dorpat in Estonia. This brought the Sword Brethren into conflict with the Russians since Dorpat was controlled by the city of Pskov, which in turn was controlled by the Principality of Novgorod. With its conquest, Hermann Von Buxhoeven became the Bishop of Dorpat, which made him the de facto ruler of Livonia. Though never numerous, the Sword Brethren persevered against the fearsome pagans.

The Danes also began carving out a sphere of influence for themselves in the eastern Baltic. Danish King Valdemar I, who ascended to the throne in 1154, sent Christian Danes to the eastern Baltic where they succeeded in establishing a foothold in Estonia. This was initially done for economic rather than religious reasons, although that would eventually change.

In 1218 Pope Honorius III authorized Valdemar to crusade in Estonia and granted him permission to annex land in the area for that purpose. Simultaneously, Bishop Albert asked the Danes to attack the pagan Estonians from the north while the Sword Brethren assailed them from the south. The Danes gladly obliged.

The Sword Brethren were not the only Catholic military order involved in the Baltic region. The Order of the Hospital of Saint Mary of the Teutons in Jerusalem, better known as the Teutonic Order, was heavily involved in converting pagan Prussians. The order had been founded in 1190 in the Holy Land to defend the port of Acre in the dwindling Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Papacy officially recognized the new military order in February 1199.

Because their prospects in the Holy Land were limited given that the military orders known as the Templars and Hospitallers were firmly established in the region, the Teutonic Order’s fourth grand master, Hermann Von Salza, began looking for fresh opportunities outside the Outremer for his warrior monks. Count Hermann of Thuringia, who was the suzerain of the Von Salza family, suggested in 1210 that Von Salza explore the possibility of aiding King Andrew II of Hungary, whose kingdom was frequently ravaged by raids conducted by the nomadic Cumans who lived on the Eurasian steppe east of the Carpathian Mountains.

In the discussions that followed, King Andrew outlined the need for the Teutonic Knights to guard the Burzenland, a part of Transylvania that lay in the western foothills of the Carpathians. Andrew offered them lucrative terms. He agreed to forego the customary taxes, duties, and tolls imposed on his vassals; however, he maintained the right to administer justice, establish markets, and claim half of any gold and silver that was discovered in the Burzenland. In 1211 Von Salza excitedly accepted the offer. He had only the king’s verbal agreement, however.

Von Salza, who remained in Acre, dispatched a large contingent of Teutonic Knights to the Burzenland. The knights arranged for large numbers of German peasant volunteers to relocate to the Burzenland. Their role was to help the knights construct wooden forts from which to garrison the countryside. In addition, the German peasants would establish permanent farms. The Teutonic Knights would collect taxes on the farms, as well as on the harvests, to fund the fortified outposts and subsequent military operations. It was a tried and true method used by the military orders. A steady stream of immigrants from Germany poured into the Burzenland in the following years.

In 1217 King Andrew departed his realm to participate in the Fifth Crusade. In his absence, the Teutonic Knights began expanding east of the Carpathian Mountains. This was easily accomplished, for the nomadic Cumans had no interest in holding terrain. By 1220 the Teutonic Knights had begun to build stone castles in the newly conquered regions. By this time, the Hungarian boyars (aristocrats) were extremely jealous of the Teutonic Knights both because of the incomes they derived from agricultural activities, and also because of the new lands they possessed as a result of their conquests. When Andrew returned home in 1221 he found his kingdom in an uproar over the success achieved by the Teutonic Knights. The boyars insisted that the crusaders had overstepped the bounds and authority of the original agreement. They demanded that King Andrew rescind the land grants he had given to the Teutonic Order. For the most part, Andrew continued to honor his agreement. He found no fault with the Teutonic Knights.

But Von Salza worried that the Teutonic Knights in the Burzenland were dangerously exposed both politically and militarily. He therefore implored Pope Honorius to put the Knights in the Burzenland under his protection. Honorius obliged the grand master and made Transylvania a fief of the Holy See.

When he learned what Von Salza had done, King Andrew flew into a rage. He demanded in 1225 that the Teutonic Knights leave Hungary at once. He even ordered his eldest son, Prince Bela, to assemble the Hungarian army to oust the Teutonic Knights by force if necessary. The Teutonic Knights departed the Burzenland never to return. It was an embarrassing episode, and one that Von Salza did not want to occur again in another location.

Another opportunity arose the following year in Poland. Duke Konrad I of Mazovia invited the Teutonic Knights to assist him in fighting the hostile pagan Prussians who bordered Mazovia to the north. In return for their service, Konrad offered to give the Teutonic Knights the province of Chelmno, which lay between the Vistula and Drewenz Rivers.

As a result of the debacle in Hungary, Von Salza went to great lengths to negotiate an arrangement whereby the Teutonic Knights would be guaranteed autonomy in regard to the administration of Chelmno. Duke Konrad’s promises alone were not sufficient. Von Salza requested official decrees from both Pope Gregory IX and Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II that the Teutonic Order would not only have control of Chelmno, but also any territory that it subsequently conquered.

While these events were unfolding, the Sword Brethren were overextending themselves in the Baltic region. In the summer of 1236 the Brethren decided to launch an invasion of Lithuania. A force of 50 mounted crusaders marched south toward Lithuania. After crossing the Livonian-Lithuanian border, the Brethren encountered marshy land along the Saule River that slowed their progress. Suddenly they were showered with javelins thrown by pagan Samogitians. After unhorsing the knights, the Samogitians closed in on them. Although the knights fought fiercely with their broadswords, they were wiped out by spear-wielding Samogitians. The defeat irrevocably crippled the small military order.

Von Salza and a representative of the Sword Brethren traveled to Rome where they met with Pope Gregory IX to gain approval for the incorporation of the Sword Brethren into the Teutonic Order. Because the Sword Brethren had become haughty and disobedient in their administration of Livonia, Pope Gregory was more than willing to see them assimilated into the well-established and orderly Teutonic Order.

In the wake of the union that became official on May 12, 1237, the Teutonic Knights arrived in greater numbers in Livonia. In the years that followed, the Knights gradually subjugated the pagan Curonians, Semigallians, and Samogitians of Lithuania. Although the pagans were compelled to convert to Christianity, they were allowed to keep their forts and govern themselves. In return for autonomy, the tribes had to agree to fight for the Teutonic Order when requested.

The Orthodox Russians did not share the Catholic Christian zeal to convert pagans. Medieval Russia had coalesced in the 9th century when the Scandinavian Varangians conquered the lands in northwestern Russia inhabited by the East Slavs who lived on the Eurasian steppe. Varangian Prince Rurik made Novgorod his seat of power in the 850s. He ruled an area that stretched from Novgorod south to Kiev. When Rurik left Russia in 873 to rule over Friesland, which had been left to him by his late father, his kinsman Oleg took control of his domain in Russia. To legitimize their reign, the founders of Kievan Russia claimed to be descendents of Rurik.

By the early 13th century Russia was composed of 10 principalities, each of which was named after its main city. Prince Vladimir the Great, the grand prince of Kiev, had officially adopted Orthodox Christianity in the 10th century. The northernmost principality, Novgorod, was surrounded by swamps and had very little arable land; therefore, its inhabitants made their living by commerce rather than farming. In 1236 the Vsevolodovich dynasty led by Yaroslav II seized control of Novgorod following a complex struggle for power. As a result of responsibilities he had in other parts of Russia, Yaroslav sent his 15-year-old son Alexander to be the prince of Novgorod. Although Alexander knew that the Germans and Danes who had settled in Livonia and Estonia posed a threat to Novgorod, he faced a greater threat coming from Asia.

Mongol generals Subutai and Jebe had smashed the Christian Georgians on the Kuban River in 1222. The Mongols typically attacked in the winter when frozen rivers, streams, and marshes posed no obstacle to their mounted armies. After their victory in Georgia, they swept north into southern Ukraine where they vanquished a Russian-Kipchak army at the Kalka River in 1223. A long hiatus occurred before the Mongols returned to continue their attacks in the west.

In the winter of 1237-1238 Subutai and Ghengis Khan’s grandson Batu led the Mongols on an offensive to complete their conquest of Russia. After conquering several Russian principalities, they failed to capture Novgorod because an early spring thaw had slowed their horsemen. It was a fortunate occurrence, for Prince Alexander had neglected to establish any defenses to slow the Mongols. Alexander, who knew his troops were no match for the elite Mongol warriors, struck a deal with the Mongols whereby Novgorod agreed to become a subject state and pay tribute.

Following the assimilation of the Sword Brethren into the Teutonic Knights in the spring of 1237, Papal envoy William of Modena brokered a deal with the Danes whereby the Teutonic Knights would administer Livonia while the Danes governed Estonia. With Novgorod agreeing to become a Mongol vassal, Modena and the Teutonic Knights believed the time was right to launch their own offensive against Novgorod. Modena therefore began preaching a crusade against the Orthodox Novgorodians.

Modena was acutely aware that crusades were costly endeavors. What is more, they also involved formidable logistical challenges. This would certainly be the case in regard to the new crusade because of the harsh climate of northern Russia. Nevertheless, he pressed on with his plans, knowing that the crusade enjoyed the full support of Rome.

Participating in a Northern Crusade was similar to participating in one in the Holy Land. Those who decided to take the cross would receive both material and spiritual benefits. Their personal assets would be protected and their sins would be forgiven. If a participant fulfilled his oath and completed the crusade, then all of his secular crimes would be forgiven. In addition, a crusader could keep any plunder obtained during the crusade, although he was expected to make a tithe to the Catholic Church.

The engagements that occurred in the Baltic typically consisted of skirmishes and raids. The dense forests and large marshes forced soldiers to deploy along well-established and predictable routes. These routes, many of which followed waterways, exposed the troops to possible ambushes. Like the Mongols, the crusaders found it easier to campaign in the winter months despite the frigid temperatures. Although the cold temperature adversely affected the men both physically and mentally, the crusaders, like the Mongols, knew that it was easier to cross frozen rivers and marshes in the colder months.

In the first half of 1240 a Swedish contingent landed at the confluence of the Izhora and Neva Rivers in northern Estonia. Their purpose was to seize control of the mouth the Neva and the city of Ladoga in order to control trade through those points. The Swedish force, which was led by Swedish Earl Karl Birger and Bishop Thomas of Finland, comprised Norwegians, Finns, and Tavastians. Alexander perceived the Swedish outpost as a threat to Novgorod.

To counter the threat, he organized a mobile strike force of Novgorod boyars who were well equipped and well trained. On July 15, 1240, Alexander smashed the Swedes on the banks of the Neva. In the aftermath of his decisive victory over the Swedes, Alexander received the sobriquet Nevsky, meaning “of Neva.”

Alexander’s rise in popularity among the people of Novgorod and his increased authority following the Battle of the Neva produced strained relations with the boyars of Novgorod. The backlash was so significant that Alexander departed Novgorod shortly thereafter for his father’s principality of Pereyaslavl.

While Alexander was living in Pereyaslavl, William of Modena continued planning the so-called Novgorod Crusade. The crusade would involve Teutonic Knights, Danes, and Swedes. Local Estonians would serve as foot soldiers for the mounted forces. The Danes were led by princes Canute and Abel, and the native Estonian auxiliaries were the responsibility of Bishop Hermann of Dorpat. Prince Jaroslav, an exiled Russian boyar from Pskov, joined the crusaders in the hope that he could one day rule Pskov.

Modena planned a three-pronged offensive against Novgorod. The Swedes would sail into the Gulf of Finland and land near the present-day site of St. Petersburg where they would take up a blocking position to prevent the Finns from reinforcing their Novgorodian allies. As for the Danes, they would march north from Estonia traveling along the Baltic coast to Narva and then proceed to Koporye, a town situated northwest of Novgorod. The Teutonic Knights would capture Pskov at the southern end of Lake Peipus. After achieving these objectives, the three columns would manuever to capture Novgorod.

Modena was an ecclesiastical official, not a military man. His plan for the campaign had glaring deficiencies. The most obvious oversight was that the forces would be too far apart to reinforce each other should one of them need assistance.

In September 1240, the Teutonic Knights captured the fortress of Izborsk. A force of 600 militia from Pskov set out to retake Izborsk. The crusaders soundly defeated the Pskovians on September 16, 1241. The crusaders subsequently besieged Pskov. After the crusaders had spent a week ravaging the area around Pskov, the residents of Pskov surrendered their city to the crusaders. A pair of Teutonic knights and a small number of troops remained in Pskov with a detachment of Prince Jaroslav’s levies to garrison the city.

The death of Danish King Valdemar II on March 28, 1241, compelled princes Canute and Abel to return to Denmark; however, the Danes and their Estonian vassals already were committed to the offensive against Novgorod. The Danes successfully captured Koporye. To defend the site, they began constructing a stone castle, but they had only completed a single tower when they were faced with a Russian attack.

The successful advance of the crusaders sparked great alarm in Novgorod. In response the city’s veche (popular assembly) sent a request to Alexander’s father that he order his son to return to Novgorod to lead the defense of the principality. Instead, Alexander’s father sent Andrey Vsevolodovich of Suzdal, who was Alexander’s brother. The people of Novgorod were not content with Suzdal, and they reiterated their request for Alexander.

In response to the clamor, Alexander set out for Novgorod in the autumn of 1241. His druzhina (retinue) proceeded swiftly to Koporye where it captured the crusader-built tower. Alexander paroled the crusader prisoners, but he ordered the Estonians hung. At that point, Alexander had defeated two of the three prongs of the crusader invasion. He had beaten the Swedes on the banks of the Neva River, and he had smashed the Danes at Koporye.

During the winter of 1241-1242, Alexander was reinforced by his brother Andrey. With the addition of Andrey’s troops, Alexander had an army of 5,000 men. The Russian army was composed of 800 druzhina cavalry, 200 Novgorod horsemen, 800 Novgorod infantry, 2,000 feudal infantry, and 1,200 horse archers. Andrey had recruited the horse archers. It is not clear whether the mounted archers were Turkish or Mongol. On the one hand, they may have been part of a Mongol invasion force that remained in the Principality of Suzdal when it became a Mongol subject state. On the other hand, they might possibly have been Kipchaks or Cumens from the Eurasian steppe.

Alexander decided in February 1242 to conduct an offensive to retake Pskov. The harsh winter conditions meant the marshes and waterways were frozen over and Alexander most likely used this to his advantage to once again strike the enemy before they knew what was happening. He also knew that speed was a necessity since an early thaw might occur at any time. He captured Pskov on March 5. Shortly afterward Alexander led his troops across the frontier into Livonia. He had carefully weighed the pros and cons of invading Livonia. In the end, his desire for revenge was so great that he decided it merited an invasion of enemy territory.

Alexander divided his army into several independent detachments in order to inflict maximum destruction on the enemy. One of these raiding parties was led by Domash Tverdislavish, a Novgorod boyar. A group of crusaders attacked and routed Tverdislavish’s force near the village of Mooste. Tverdislavish and many of his men were slain the encounter. Those that escaped warned Alexander that a large force of crusaders was in the area.

Alexander and his brother quickly gathered their raiding parties. They decided to return to Novgorod by the most direct route, which would mean marching across the frozen surface of Lake Peipus.

Bishop Hermann led the crusader army in pursuit of Alexander. His 1,020-man force consisted of 20 Teutonic Knights, 200 Teutonic sergeants, 300 Danish knights, and 500 Estonian auxiliary infantry.

Lake Peipus lay astride the Livonian-Novgorodian border. It has a very flat shoreline that consists of both small beaches and reed banks. The narrowest part of the hourglass-shaped body of water is very shallow. The prevailing wind on Lake Peipus is from the west. The ice, which thaws and refreezes, piles up against the eastern shore, forming a series of jagged peaks and ridges.

Alexander learned from his scouts the path of the crusader advance and swung his force north to avoid them. The Novgorod army skirted to the north around the village of Mehikoorma and then crossed the frozen lake at the narrow section. When Alexander reached the far side, he led his troops a short distance north to a small, flat peninsula known as Raven’s Rock. He then deployed his army behind the jagged ice floes, which he planned to use as a defensive barrier. Alexander positioned his troops on the edge of the lake facing west to receive the crusader attack.

Bishop Hermann’s crusaders departed the village of Tartu, which lay due west of the frozen marshes on the west side of Lake Peipus. The bishop was elated at the chance to pursue Alexander’s force because he believed he had caught the enemy in full flight. He hoped to cut off the Russian escape, but the Russians were too quick. When the crusaders reached the lake, they crossed to the north of the Russians where they could work their way from one small island to the next as they crossed the ice. They soon sighted the Russians waiting for them on the eastern shore.

Alexander placed the Novgorod militia in the center. These foot soldiers wore conical helmets, quilted jackets, and small circular breastplates. Most were armed with either a long spear or a long-handled axe. The Novgorod militia also had a number of skilled archers. The cavalry formed on both sides of the infantry. Alexander ordered the elite troops of his druzhina to form a second line behind the center where they would serve as the reserve. The majority of the horse archers deployed on the right wing.

The crusaders attacked in their traditional blunt wedge formation known as a “boar’s snout.” They moved toward the Russian position in close order. Bishop Herman and the heavily armored Teutonic Knights were in the center of the wedge. The Danish knights of Livonia formed the left wing, and the Livonian knights were on the right. The Estonian infantry followed behind.

Bishop Hermann’s army charged across the ice toward the center of Alexander’s line, probably with the intent of killing or capturing him. The charge was difficult given that their horses had to make their way across the slippery ice. Because of these conditions, it is likely that the charge lacked the full momentum that would have been achieved on dry ground.

Nevertheless, the crusaders crashed with great force into the Russian line, trampling many of the Russian infantry in the center. The knights on their great steeds cleaved all around them, slaying large numbers of the Russians. The German knights desperately sought to reach Prince Alexander, but he was safely positioned with the reserve.

Although heavily outmatched by the German knights, the Novgorod militia did not break. Sensing that his center was in serious danger, though, Alexander ordered his light cavalry stationed on both flanks to encircle the crusaders and their allies. The lightly armored horsemen on both flanks of the Russian army advanced onto the ice to carry out the prince’s order. The horse archers who were deployed in the Russian right wing began to enfilade the left flank of the crusader army. They fired thick showers of arrows into the gray sky that whistled downward with great force into the enemy ranks. The Danish knights suffered heavy casualties as a result of their exposure to the arrow storm.

The crusader attack soon bogged down. The crusaders’ banners “were soon flying in the midst of the archers, and swords were heard cutting helmets apart,” stated the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle, an account believed to be written by an anonymous participant in the crusade. “Many from both sides fell dead on the grass. Then the [crusader] army was completely surrounded, for the Russians had so many troops that there were easily 60 men for every one German knight.”

The local Estonian auxiliaries hung back to watch the crusaders fight the Russians. They feared the Russians and had no intention of joining the fight if they could possibly avoid it. When they observed the crusader attack flagging, they retreated in the direction from which they had come. Thus, they quit the battle without ever having supported the mounted attack.

The Danish horsemen soon began to retreat as well. Having been decimated by the arrow storm, they rode hard for the western shore of the lake with the Russian cavalry in close pursuit. Although some fighting occurred on the ice during the crusader retreat, it is unlikely that any troops fell through the ice, as some accounts suggest, because the water was no more than a foot deep. The surviving German knights soon retreated, too.

Alexander’s troops broke off their pursuit when they reached the far shore, for the Novgorod prince had told them not to reenter Livonian territory. Instead, the Russian horsemen turned back to run down the Estonian infantrymen who had not made it to safety.

Twenty of the crusader knights died and six were captured, according to the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle. The crusaders likely lost 45 percent of their force. The Russian foot soldiers bore the brunt of the Novgorodian casualties. Contemporary accounts do not give figures for Nevsky’s losses.

“The [crusaders] fought well enough, but they were nonetheless cut down,” states the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle. “Some of those from Dorpat escaped the battle, and it was their salvation that they fled.”

Alexander’s defeat of the crusaders on the frozen shore of Lake Peipus put an abrupt halt to the eastward expansion the Teutonic Order. The Novgorod Crusade had failed largely because William of Modena had not assembled enough troops and resources to defeat Prince Alexander’s army. In addition, the Teutonic Knights’ overconfidence had led them to believe they could easily defeat the Russians. Neither William of Modena nor Bishop Hermann had foreseen the degree to which the extant Russian principalities that had survived the Mongol onslaught would cooperate with each other when faced with external aggression.

In the aftermath of the defeat, the Teutonic Knights had to return control of Izborsk to the Novgorodians. Having been humbled by their defeat, the Teutonic Knights subsequently focused their crusading efforts in the region on converting pagans to Christianity in Prussia and Lithuania, thus leaving a minimal presence in Livonia and Estonia.

The Teutonic Order also made key reforms after assimilating the Sword Brethren. Instead of allowing recruits of both high and low birth to join the military order as the Sword Brethren had done, the Teutonic Knights allowed only those of noble birth to become knights.

Not long after the battle the Estonians rose up against their Danish overlords and the Prussians revolted against the Teutonic Knights. It is possible that the rebellions were inspired by the success the people of Novgorod had against the Catholic crusaders. The Prussians received substantial support from Christian Slav Duke Sventopolk of Pomerallia. While the Teutonic Knights were heavily engaged in suppressing the revolt, they also had to guard against encroachment on their territory by German colonists, Polish princes, and the Knights of Dobryzn. The major revolt lasted for seven years, from 1242 to 1249. The Danes grew weary of administering Estonia, so in 1346 they sold it to the Teutonic Knights.

The rivalry between Catholic and Orthodox Christians in the eastern Baltic region also was tempered in the wake of the battle by Pope Innocent IV’s efforts to establish peaceful relations with the Russians.

Alexander Nevsky had shown that he possessed both shrewd political skills and a talent for military leadership. When the threat of a crusader invasion loomed large, he had acted swiftly and resolutely. Moreover, he fielded an army with the technical proficiency to defeat a crusader army. Through their knowledge of Mongol warfare and the lessons of Kalka River, both Alexander and his brother were confident that the horse archers could decimate an opponent.

The victory achieved by the Principality of Novgorod was a significant event in the evolution of Russia. It showed that the Russians could defeat Latin crusaders in battle. Alexander also knew that it was in the best interests of his people not to continue the war by invading the territories held by the Teutonic Order and the Danish crown. Although the Teutonic Order had suffered an important defeat, its garrisons along the Baltic seaboard were too strong for the Russians to conquer. He offered the crusaders generous terms, which they gladly accepted. The agreement produced two decades of peace between the Russians and the Teutonic Knights. Alexander soon had to go to war with the pagan Lithuanians to curb their repeated raids into Novgorod territory.

The Teutonic Knights were eclipsed in the following centuries by the rise of Poland and Lithuania, which had joined together in 1385 in a mutually beneficial union. The combined forces of the two great states subsequently defeated the Teutonic Knights in 1410 in the Battle of Grunwald.

Although descriptions of his actions in medieval histories borders on the supernatural, the truth is that his military abilities combined with his political shrewdness turned Alexander into a national hero. Alexander had superb political and military skills. He was able to remain at peace with the Mongols by using diplomacy.

After showing that foot soldiers could defeat highly trained and well-armed knights mounted on horseback, Alexander negotiated a treaty with the Teutonic Order in 1243 by which the order abandoned its claims to Russian territory. In 1547 the Orthodox Church canonized Prince Alexander as a saint.

Alexander Nevsky remains a heroic figure in Russian history. This is reflected in the “Order of Alexander Nevsky,” which often has been used as one of the country’s highest military decorations.

The Russian Orthodox Church knew all too well how significant Prince Alexander was to the Russian people. On November 14, 1263, Archbishop Kiril was leading a service at Vladimir Cathedral in Suzdal when he learned that the prince had died. He turned to the congregation and said, “The sun of the Russian land has set, my children.”