By Michael D. Hull

January 1945—with World War II in its sixth year—found the Allied armies going on the offensive after the Battle of the Bulge, but they were still west of the Rhine and six weeks behind schedule in their advance toward Germany.

Closing to the Rhine was not easy. Although U.S. and French units of Lt. Gen. Jacob L. Devers’ Sixth Army Group had reached the western bank around Strasbourg in late 1944, the river proved too difficult to cross. Even if an assault could have been mounted, the Allied forces would have been too far away from the heart of Germany to pose any meaningful threat. The key to eventual victory lay in the central and northern Rhineland, but three factors delayed an advance: the failure of Operation Market Garden, the British-American airborne invasion of Holland, the onset of an extremely wet autumn and harsh winter, and the unexpectedly rapid recovery of the German Army in the wake of recent Allied advances.

A coordinated Allied campaign proved difficult to achieve. General Omar N. Bradley’s U.S. 12th Army Group was licking its wounds after the almost disastrous Ardennes counteroffensive, and it was clear to Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery, commander of the British 21st Army Group, that the Americans would not be ready to undertake a major offensive for some time. Despite its vast reserve of manpower, unlike the critically depleted British Army, the U.S. Army had become seriously deficient of infantry replacements. Monty made the first move.

Meanwhile, on January 12, the Soviet Army launched a long-awaited, massive offensive from Warsaw toward the River Oder—and Berlin. This was just in time, thought Montgomery and General Dwight D. “Ike” Eisenhower, the Allied supreme commander. By the end of the month, the Russians were only 50 miles from the German capital. While the Americans were recovering, it devolved on the 21st Army Group, still supported by Lt. Gen. William H. “Texas Bill” Simpson’s U.S. Ninth Army, to take over the battle as soon as winter loosened its grip.

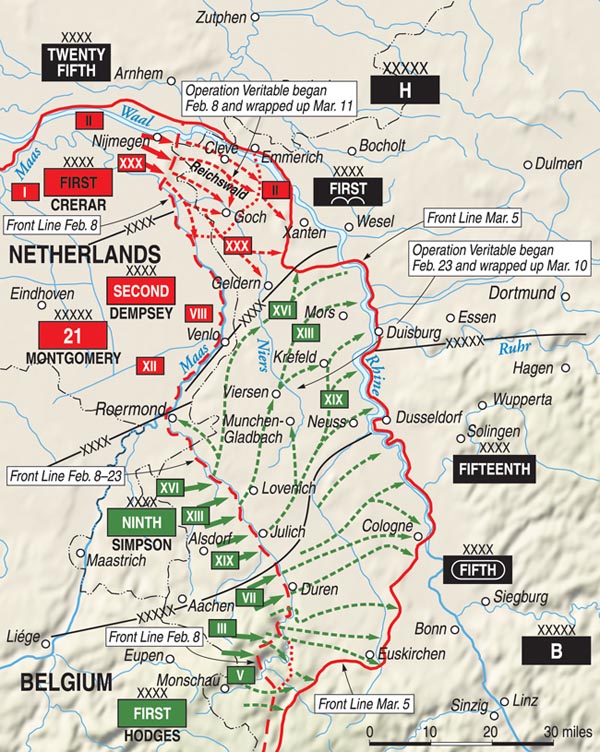

Monty and Ike agreed that the next stage should be to break through the Germans’ formidable Siegfried Line and close up to the left bank of the Rhine. The main objective was the historic city of Wesel, on the opposite side of the great river in flat country just north of the Ruhr Valley. It was here that Montgomery had originally sought to seize a bridgehead in September 1944, and common sense still favored it. Accordingly, two well-knit, almost copybook offensives were planned for February 8, 1945: Operation Veritable on the left flank and Operation Grenade on the right, adjacent to the boundary with Bradley’s 12th Army Group.

Monty announced that the 21st Army Group’s task was to “destroy all enemy in the area west of the Rhine from the present forward positions south of Nijmegen (Holland) as far south as the general line Julich-Dusseldorf, as a preliminary to crossing the Rhine and engaging the enemy in mobile war to the north of the Ruhr.” Three armies would be involved in the offensives: the Canadian First, the British Second, and the U.S. Ninth.

Commanding the Canadian force was the distinguished, 57-year-old General Henry D.G. “Harry” Crerar, a World War I artillery veteran and a man of cool judgment and cold nerves. The “ration strength” of his First Army exceeded 470,000 men, and no Canadian had ever led such a large force. The British Second Army was led by the skilled, unassuming Lt. Gen. Sir Miles “Bimbo” Dempsey, a 48-year-old World War I veteran of the Western Front and Iraq who later acquitted himself well in the Dunkirk evacuation, the Western Desert, Sicily, Italy, and Normandy. Tall, bald, Texas-born General Simpson, commanding 300,000 men of the U.S. Ninth Army, had served in the Philippine Insurrection, the 1916 Mexico punitive expedition, and on the Western Front in 1918. Eisenhower said of the 56-year-old officer, “If Simpson ever made a mistake as an Army commander, it never came to my attention.”

With 11 divisions and nine independent brigades, the Canadian Army would clear the way in February 1945 up to the town of Xanten; the Ninth Army, with 10 divisions in three corps, would cross the Roer River and move northward to Dusseldorf (Operation Grenade), and the four divisions of the Second Army would attack in the center.

Although he was in customary high spirits about the operation, Montgomery knew that it would be no cakewalk. “I visited the Veritable area today,” he warned Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, chief of the Imperial General Staff, on February 6. “The ground is very wet, and roads and tracks are breaking up, and these factors are likely to make progress somewhat slow after the operation is launched.” Besides expected opposition from at least 10 well-entrenched Wehrmacht divisions, the Allied troops would have to face minefields, flooded rivers and terrain, a lack of roads, appalling weather, and tough going in the gloomy, tangled Reichswald and Hochwald forests.

Montgomery won final approval for the great dual assault on the Rhine on February 1, and the preparations were hastily finalized under tight security. Strict blackout regulations were enforced, and a cover story was concocted to convince the enemy that the offensive would be in a northerly direction to liberate Holland, rather than an eastern thrust into Germany. Daytime gatherings of troops were forbidden unless under cover; large concentrations of vehicles, weapons, and ammunition were camouflaged or concealed in farmyards, barns, and haystacks, and rubber dummies of tanks and artillery pieces were positioned along an imaginary battle line where they might attract the attention of enemy patrols. Logistical feats were accomplished speedily as thousands of men, vehicles, and equipment were transported to the forward assembly lines.

The British and Canadian soldiers worked around the clock. Sappers built and improved 100 miles of road using 20,000 tons of stones, 20,000 logs, and 30,000 pickets, and 446 freight trains hauled 250,000 tons of equipment and supplies to the railheads. It was estimated that the ammunition alone—all types, stacked side by side and five feet high—would line the road for 30 miles. Engineers constructed five bridges across the River Maas, using 1,880 tons of equipment. The biggest was a 1,280-foot-long British-designed Bailey bridge. Outside Nijmegen, an airfield was laid in five days for British and Canadian rocket-firing Hawker Typhoons, which would support the offensive.

Meanwhile, a formidable array of armor and specialized vehicles was assembled. It included Churchill, Cromwell, Centaur, Comet, Valentine, and Sherman heavy and medium tanks; Bren gun carriers, jeeps, half-tracks, and armored cars; amphibious Weasel, Buffalo, and DUKW cargo and personnel carriers; and 11 regiments of “Hobart’s Funnies,” Churchills and Shermans fitted with antimine flails, flamethrowers, and bridging equipment. Invented by Maj. Gen. Sir Percy Hobart, these had proved invaluable in the Normandy invasion and the clearing of the flooded Scheldt Estuary by Crerar’s army.

Under the command of the Canadian First Army, the Veritable offensive was to be spearheaded by the seasoned British XXX Corps led by 49-year-old Lt. Gen. Sir Brian G. Horrocks. He returned from leave in England to plunge into preparations for the largest operation he had ever undertaken. A much-wounded veteran of Ypres, Siberia, El Alamein, Tunisia, Normandy, and Belgium, the tall, lithe Horrocks—nicknamed “Jorrocks” by his mentor, Montgomery—was a charismatic officer who led from the front and was regarded as one of the finest corps commanders of the war.

Horrocks regarded Monty’s overall plan for the offensive as “simplicity itself.” The XXX Corps was to attack in a southerly direction from the Nijmegen area with its right on the River Maas and its left on the Rhine. “Forty-eight hours later,” said Horrocks, “our old friends, General Simpson’s U.S. Ninth Army, were to cross the River Roer and advance north to meet us. The German forces would thus be caught in a vise and be faced with the alternatives, either to fight it out west of the Rhine or to withdraw over the Rhine and then be prepared to launch counterattacks when we ourselves subsequently attempted to cross…. In theory, this looked like a comparatively simple operation, but all battles have their problems, and in this case the initial assault would have to smash through a bottleneck well suited to defense and consisting in part of the famous Siegfried Line.”

Horrocks decided to use the maximum force possible and open Operation Veritable with five divisions, from right to left, in line: the 51st Highland, 53rd Welsh, 15th Scottish, and the 2nd and 3rd Canadian, followed by the 43rd Wessex and Maj. Gen. Sir Alan Adair’s proud Guards Armored Division. On the morning of February 4, Horrocks briefed his commanders in the packed cinema in the southern Dutch town of Tilburg. Clad in brown corduroy trousers and a battlefield jacket, the unpretentious general drew a warm response as he crisply outlined the offensive, radiated confidence, and moved from group to group with a friendly and humorous word. Like Montgomery, he made a practice of keeping all ranks informed about operations.

Despite his recurring pain and high fever incurred after being seriously wounded by a German fighter plane in Bizerte two years before, Horrocks was hopeful as the D-day hour neared. But he and General Crerar grew concerned when three days of heavy rain made the roads muddy and slushy. A hard crust of ice that would have ensured the rapid movement of men and armor had thawed, and the roads were sinking.

On February 7, men of the Canadian 1st Scottish Regiment peered across the surrounding fields and were alarmed to see them waterlogged. As a defense measure, the Germans had blasted holes in the Rhine’s winter dikes, and a foot of water now covered the entire area. The flood level reached 30 inches in two hours and was rising at the rate of one foot each hour. Half of the battlefield ahead of Crerar’s army was soon under five feet of water, and the rest of the polderlands bordering the Rhine were a muddy morass. Silent but alarmed, Horrocks listened to reports filtering into his command post. How could 90,000 men and vehicles of his spearhead force be funneled into action through murky water and along roads that were now muddy ruts? But the lines were drawn, and he prayed that this might be the final battle of the long war.

The British and Canadian assault troops waited anxiously on February 7, oiling and loading rifles and machine guns, topping up the fuel levels in tank engines, scribbling letters home, and trying to get some rest. But there was little sleeping that night when the dark sky was rent by great flashes and distant explosions. Aimed at softening up the German defenses, 285 Avro Lancaster heavy bombers of Royal Air Force Bomber Command, led by 10 De Havilland Mosquito pathfinder fighters, thundered overhead. They flattened a number of Rhineland towns that were known to be enemy strongpoints, including Goch, Weeze, Udem, Geldern, and Calcar.

Especially hard hit that night was the beautiful, historic city of Cleve, the gateway to the Rhineland and the key rail and communications center through which the Germans could funnel reinforcements. The Lancasters dropped 1,384 tons of high explosives on Cleve, an inspiration for Richard Wagner’s Lohengrin and the birthplace of King Henry VIII’s meek, homely fourth wife, Anne. Cleve was more devastated than any other German city of its size during the war. Generals Crerar and Horrocks agreed that the RAF raid was tactically necessary to save many Allied lives, but the latter “simply hated the thought of Cleve being ‘taken out.’”

Horrocks recalled later, “It was the most terrible decision I had ever had to take in my life. I felt almost physically sick when I saw the bombers flying overhead on their deadly mission.” He blamed the RAF for dropping high explosives instead of incendiaries, which he had requested, and for reducing Cleve to rubble and huge craters that later held up the Allied advance.

At 5 am on Thursday, February 8, 1945, while Cleve still burned, a massive artillery bombardment paved the way for Operation Veritable. Lined up between 10 and 15 yards apart, 1,400 field and antiaircraft guns of numerous calibers, mortars, medium machine guns, and high-explosive rocket launchers opened up with a deafening roar. It was the heaviest barrage employed so far by the British Army during the European war—greater than anything in Normandy and the historic bombardment at El Alamein on October 23, 1942. More than half a million shells were put down on a seven-mile front.

The Veritable barrage lasted for 21/2hours on that gray, rainy morning as General Horrocks watched and listened from a command post platform that Royal Engineers had built halfway up a large tree. “The noise was unbelievable,” he reported. Below him, the area teemed with armored vehicles, and the air was filled with the roar of engines.

When the artillery barrage stopped, there was an eerie silence as smoke was fired across the XXX Corps front. This was aimed at making the Germans think that the infantry attack had been launched. Enemy gunners who had survived the first bombardment then rushed to their weapons and opened up. British flash spotters zeroed in on the battery positions, and, after 10 minutes of silence, the Allied barrage erupted again, concentrating on the German guns that had been located. In addition to the artillery, each British and Canadian division employed “pepper pot” tactics, with every weapon not used in the assault blasting enemy positions. The effect was so devastating that when Horrocks’ men went forward the German gunners were still crouching in their trenches.

The XXX Corps tanks and infantry advanced against befuddled enemy defenders, and little initial resistance was met. “The enemy had been over-awed by the bombardment,” observed Captain Peter Dryland, adjutant of the 7th Battalion of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. But continual rain had turned the terrain into a quagmire, and the Allied tanks and infantrymen had to struggle through mud. “Our worst enemies that day were mines and mud,” Horrocks reported. “Mud, and still more mud.”

Personnel carriers carrying troops heaved through the mire, and supporting tanks ploughed into the woods. But it was tough going from the start. After the first hour almost every Allied tank had bogged down, and the infantry had to forge ahead on their own. Some tanks simply sank in the mud, others hit mines, and still others were blocked by felled trees or craters gouged by the Allied bombing and artillery barrage. Yet the British and Canadian riflemen and tankers pushed on doggedly.

On the left flank the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division cut the main Nijmegen-Cleve road, and then half of the force turned back to attack and capture the strongly held village of Wyler after a stiff fight. The other half moved to support the 15th Scottish Division advancing on the right, while its 44th Brigade pushed through minefields to breach the northern extension of the concrete and steel Siegfried Line. Meanwhile, on their right men of the tough 53rd Welsh Division disappeared into the dense, gloomy Reichswald, pushing through tangled thickets and along narrow, soggy trails. Farther to the right, the famed 51st Highland Division plunged into the southern part of the Reichswald, east of the River Maas, and encountered strong German opposition.

Conditions worsened for the Allied troops. Flood levels rose steadily, and the only narrow road in the Reichswald available for the advance was soon under several feet of water. The enemy opposition increased, with heavy artillery barrages and the hasty deployment of fresh reserves, including two armored and two parachute divisions. Eventually, a total of 10 divisions—three of them armored—were battling the British and Canadian units. It was a toe-to-toe struggle in rain, sleet, and snow, with numerous hand-to-hand melees and bayonet charges, while casualties mounted alarmingly. But the attack never slackened, and the Tommies and Canucks slogged on staunchly to seize vital German positions.

The Reichswald was a soldier’s battle, influenced chiefly by the battalion commanders. General Horrocks said he was “almost powerless to influence the battle one way or the other, so I spent my days ‘smelling the battlefield.’” He made a habit of visiting brigade and battalion headquarters that were having “a particularly grueling time.

The appalling conditions endured by the Allied soldiers were reminiscent of the Battle of Passchendaele, where more than 300,000 British and Commonwealth troops were killed in 1917, and the Hürtgen Forest, in which several American divisions suffered 33,000 casualties in the autumn of 1944.

The Reichswald-Hochwald struggle was not the sort of campaign General Horrocks wished to command. It had to be fought, but it was grim and painful throughout, with no scope for brilliant tactics or avoidance of heavy losses. As a former infantryman himself, he agonized over the casualty lists, especially when they contained familiar names. Popular with both his officers and other ranks, he regarded the deaths as a great waste and personal loss.

Almost from the start of Operation Veritable, Horrocks’ corps found itself out on a limb. On February 9, the Germans blew up the discharge valves on the River Roer dams, and a wide strip of surging floodwater prevented General Simpson’s powerful U.S. Ninth Army and elements of Lt. Gen. Courtney H. Hodges’ U.S. First Army from crossing for two crucial weeks. Operation Grenade was postponed, but Simpson had the consolation of knowing that once the river had subsided the enemy could never again hold his army in check. Nevertheless, the delay had a damaging effect on Operation Veritable.

Days passed, and the fighting raged in the Reichswald. The 43rd Wessex Division fought its way through the ruins of Cleve, and, after a bitter struggle, the fortified town of Goch was taken by men of the 51st and 15th Scottish Infantry Divisions. Horrocks viewed this as the turning point in the campaign. In the smaller Hochwald, defended by fanatical German paratroopers who gave no quarter, the Canadians fought gallantly to avoid being pushed back and eventually prevailed.

Of all the many obstacles faced by the British and Canadian troops, none were more nerve wracking than the enemy minefields. Major Martin Lindsay was leading the 1st Battalion of the Gordon Highlanders through two feet of mud in an attempt to knock out a German strongpoint astride the Mook-Gennep road when he noticed that his men had grown quiet. There was a sudden explosion, and a company commander 10 yards ahead fell groaning.

Lindsay ordered everyone to stand exactly where they were and shouted for help from mine-prodders and stretcher bearers of the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa. He looked around and realized that he and his men were in a 50-yard-wide strip of no-man’s land between the German and Canadian positions. Lindsay waited, standing on one leg and not daring to put the other to the ground while the Canadian rescuers carried out the company commander and a stretcher bearer who had trodden on a mine. Each step of the way was gingerly prodded first, and Lindsay followed the other men to safety, planting his feet precisely in the tracks of the Cameron Highlander ahead.

After a week of bitter fighting through its bottleneck, the XXX Corps managed to widen the front so that General Crerar could commit the Canadian 2nd Corps commanded by the gallant, innovative Lt. Gen. Guy Simonds on the northern flank. At 42, Simonds was the youngest general ever to command a Canadian corps in battle. The 2nd Corps now bore the brunt of the assault on the strongly defended Hochwald, with the first major objectives the villages of Calcar and Udem.

It was slow, tough going for the Canadians. High-grade troops of General Heinrich von Luttwitz’s 17th Panzer Corps and General Alfred Schlemm’s First Parachute Army were well concealed and dispersed, and their defense lines were deep. Marshy fields and thick woods favored the enemy, and continual poor weather prevented the Canadians from calling in the rocket-firing Typhoons to deal with enemy strongpoints.

It took the Canadian infantry six days of harsh fighting to clear the Germans from a small, dark forest near Moyland, blocking the advance to Calcar. About three miles to the southeast, another bloody battle ensued for control of the road linking Calcar with Goch. Although the Canadians soon got astride the road, their hold on it became precarious when the Germans launched fierce counterattacks for two days, including a night thrust supported by tanks. In less than a week, the Canadians had suffered 885 infantry casualties. German losses were higher, and by now Operation Veritable had become increasingly a battle of attrition.

It was a grueling and fluctuating struggle in which the British and Canadian spearhead units, reinforced by the 11th British and 4th Canadian Armored Divisions, gained ground while trying to push through the “Hochwald Gap” and breach the 20-mile-long “Schlieffen Position,” a formidable defense line running from Udem to Geldern. But progress was slow and costly. Besides the abysmal weather and endless mud the Allied soldiers had to face more minefields, antitank ditches, and murderous fire from German panzers, deadly 88mm flak guns, and mortars. The volume of enemy barrages, which included guns fired from across the Rhine, was the heaviest encountered by British troops in the Rhineland.

Yet, against heavy odds in one of the bitterest campaigns of the European war, the gallantry of Crerar’s army and Horrocks’ corps began to pay dividends. British and Canadian troops managed to clear the last enemy units from the Reichswald on February 13 and reach the southern bank of the Rhine, opposite Emmerich, the following day. By February 17, the Canadians reached the Rhine on a 10-mile front. Meanwhile, progress was being made farther south by American units. On February 17-18, Lt. Gen. Alexander M. “Sandy” Patch’s Seventh Army crossed the River Saar and attacked near Saarbrucken, while units of Lt. Gen. George S. Patton Jr.’s Third Army breached the Siegfried Line north of Echternach, Luxembourg.

Then, before dawn on February 23, four divisions of General Simpson’s Ninth Army and two from Hodges’ First Army began to cross the River Roer at several sectors near Julich and Duren. A measure of surprise was gained because the floodwaters had not yet fully subsided, giving the German defenders a false sense of security. Simpson’s divisions suffered fewer than 100 casualties on the first day, and by the evening of February 24 his combat engineers had laid 19 bridges, seven of them fit for armor to cross. Because the Canadian First Army had drawn the bulk of the German reserves upon itself, Simpson’s army built up pressure and his armor broke away on the last day of February. His right flank reached the Rhine south of Dusseldorf two days later, and his left flank linked up with the Canadians near Geldern on March 3.

Farther north, with Wesel and its Rhine bridges only 15 miles distant, intense clashes continued between the British-Canadian forces and the Germans, who were fighting more stubbornly than ever to defend their home soil. More fresh enemy troops were deployed and new defenses hurriedly prepared. The odds against survival were still high for the Allied soldiers, especially the infantrymen. Out of 115 men of B Company of the 2nd Gordon Highlanders who had landed in Normandy seven months before, only three were left by February 26, 1945.

But the fighting spirit and discipline of the Allied troops eventually gained the upper hand. There were numerous acts of sacrifice and valor among the British and Canadian infantrymen, gunners, and tankers during the Reichswald-Hochwald campaign, and four Victoria Crosses were awarded, two of them to Canadians.

Platoon Sergeant Aubrey Cosens of the Queen’s Own Rifles distinguished himself while Sherman tanks of the 1st Hussars were trying to overwhelm stubborn German parachute troops in the hamlet of Mooshof, near the Calcar-Udem road, early on the misty morning of February 26. A quiet, tough loner from the northern Ontario backwoods, the 23-year-old Cosens directed tank fire against a farmhouse to break up an enemy attack. Braving a hail of mortar and shellfire, and armed with only a Sten gun, he dashed into the house after a Sherman had rammed it. Cosens killed at least 20 Germans and took as many prisoners, and his actions saved the lives of his men. While on the way to report to his company commander, he was shot in the head by a sniper. He was posthumously awarded Great Britain’s highest decoration for valor.

The second Canadian VC went to acting Major Frederick A. Tilston of the Essex Scottish Regiment for his gallant leadership in an assault on German defenses at the edge of the Hochwald early on the morning of March 1. During fierce fighting, the affable, mild-mannered Ontario College of Pharmacy graduate led his C Company across 500 yards of open ground and through 10 feet of barbed wire to reach two enemy trench lines. Although wounded in the head, Tilston silenced a machine-gun post with a grenade while his men cleared the trenches and then organized defenses against a German counterattack. He crossed bullet-swept ground six times to carry ammunition to a hard-pressed flanking company and received multiple shrapnel wounds in his legs. He refused medical aid. Tilston’s wounds were so severe that both of his legs had to be amputated.

By March 10, 1945, after a month of costly fighting, the Reichswald campaign was completed and the western bank of the Rhine was in Allied hands. The German high command had ordered a withdrawal on March 6, and the last pockets of enemy troops hurried across the river, destroying bridges and ferries behind them.

The toll was high on both sides in Operation Veritable. From February 8 to March 10, the Canadian First Army suffered 15,634 casualties, of whom almost two-thirds were men of the British XXX Corps. Of the 5,414 Canadian losses, almost all were in the 2nd and 3rd Infantry Divisions. German losses were an estimated 22,000, with a further 22,000 taken prisoner.

General Horrocks was deeply disturbed about the “butcher’s bill” in a campaign that was generally overlooked later even by eminent military historians. “This was the grimmest battle in which I took part during the war,” he said. “No one in their senses would choose to fight a winter campaign in the flooded plains and dense pinewoods of Northern Europe, but there was no alternative. We had to clear the western bank of the Rhine if we were to enter Germany in strength and finish off the war.” In a letter to General Crerar, Eisenhower summed up, “Probably no assault in this war has been conducted in more appalling conditions than was this one.”

Later in March 1945, Horrocks and his battered corps were heartened when British Prime Minister Winston Churchill visited them. With the 51st Highland Division’s massed bagpipes and drums sounding, Horrocks reported, Churchill “was visibly moved as he stood for the first time with his feet firmly planted on the territory of the enemy which he had been fighting for so long.”

Allied forces had closed to the Rhine, but getting across the river, swollen to 1,500 feet wide, was another matter. While Montgomery crushed the last enemy resistance in the Lower Rhineland and secured a springboard for a massive British-American crossing north of the Ruhr, the northern corps of Hodges’ U.S. First Army reached Cologne and wheeled southeast to strike the Germans in the Eifel sector. Patton’s Third Army attacked them frontally, and his freewheeling armor raced to the Rhine near its confluence with the Moselle River. But a dozen bridges between Coblenz and Duisburg were down, and every Allied attempt to seize a crossing was foiled.

Then, on the afternoon of March 7, a task force from Maj. Gen. John W. Leonard’s U.S. 9th Armored Division came upon the big Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen, 20 miles northwest of Coblenz. It was intact but set to be blown up within an hour. In one of the most dramatic feats of the war, combat engineers hastily cut the demolition cables while infantrymen raced across. Ten days later, the span collapsed from bomb damage and heavy use, but engineers had laid pontoon bridges, and the advance across the Rhine continued.

Patton’s army seized crossings at Nierstein and Oppenheim, but these and the Remagen operation could never be more than secondary. The Third Army was too far south to have a decisive impact, and the Remagen bridgehead led into the mountainous Westerwald region. The key to breaching the Rhine barrier lay firmly in the north, where Montgomery was marshaling forces for a major crossing.

At 5 pm on March 23, along the hazy western bank of the Rhine, British gunners opened up the biggest artillery barrage of the war, and Monty’s Operation Plunder—involving 1.25 million men of his 21st Army Group—was underway. Buffaloes carrying assault troops of the 153rd and 154th Infantry Brigades lurched into the dark waters and followed taped routes to the far bank. The first men to scramble ashore, around 9 pm, were Highlanders of the legendary Black Watch Regiment. The 51st Highland Division and the Canadian 3rd Infantry Division crossed the river near Rees and Emmerich, while, upstream near Wesel, Lancasters of RAF Bomber Command softened up the way for an assault by Lt. Gen. Sir Neil Ritchie’s British 12th Corps. General Simpson’s U.S. Ninth Army crossed the Rhine between Wesel and Duisburg. Although the initial crossings went smoothly and with only token resistance from German units exhausted and depleted by the actions west of the river, enemy shellfire was heavy and the 51st Highlanders had to repel a fierce counterattack by panzergrenadiers.

Within a few hours, on the sunny morning of March 24, came Operation Varsity, the subsidiary assault of the historic Rhine crossing, and much-needed reinforcements for the Allied troops on the eastern bank. Standing on a hilltop behind Xanten with Field Marshal Alan Brooke, Prime Minister Churchill shouted excitedly, “They’re here!” With a great roar overhead appeared 4,000 transport planes, tugs, and gliders of Maj. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway’s XVIII Airborne Corps. In the next 10 minutes, more than 8,000 paratroopers of the British 6th and U.S. 17th Airborne Divisions were dropped.

Meanwhile, working tirelessly and under fire, Monty’s Royal Engineers hastily laid several Bailey and pontoon bridges across the northern Rhine for the continuing Allied buildup. A total of 155 sappers were killed or wounded, and General Horrocks said, “I have always felt that the Rhine crossing was probably the sappers’ finest hour of the whole war.”

British, American, and Canadian troops and equipment were soon flowing steadily over the Rhine, and by the end of March 1945, men of General Jean Lattre de Tassigny’s French First Army had crossed the river. Every Allied army now had troops on the eastern bank, and the end of the war in Europe was only a month away.