By Nathan N. Prefer

At first, no one cared much about the forest. The objective of the First U.S. Army was the Siegfried Line, the much vaunted defensive line that protected Germany from invasion from the west.

The Hürtgen Forest was just one of several forests that lined what military planners called the Aachen Gap, a military pathway into the heart of Germany. Much of the surrounding area was impassable to military traffic because of dense pine forests in sharply compartmented terrain.

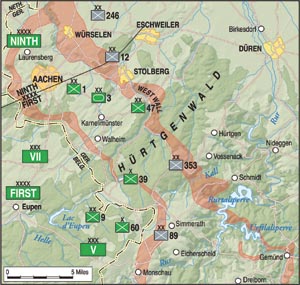

For almost 30 miles—from Verviers in Belgium to Düren in Germany on the Roer River a forest barrier running from six to 10 miles in depth bars military traffic in either direction. In Germany there were three distinct forests within this barrier, the Roetgen, the Wenau, and the Hürtgen. In this area there was only one military route east, running from Monschau to the northeast to the Roer River at Düren. To the First U.S. Army, this was known as the Monschau Corridor; a more open passage east of the German city of Aachen was known as the Stolberg Corridor.

First to approach was the VII Corps of Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins. Authorized to conduct only a reconnaissance-in-force to determine the strength of the German defenses, Collins sent forward elements of the 3rd Armored Division and 1st Infantry Division. He hoped to surprise the enemy and perhaps seize Aachen, the first major German city encountered by the Americans. But there was enough German opposition to halt the advances of both divisions. This advance, however, initiated the first battle in the Hürtgen Forest.

The American attack was conducted by Maj. Gen. Louis A. Craig’s veteran 9th Infantry Division. But in a pattern that would be repeated time and again, the full division was not available for the attack into the Hürtgen Forest. In addition to securing the Hürtgen, General Craig also had to clear the Monschau Corridor and seize high ground between Lammersdorf and Rollesbroich. As a result, only Colonel Jesse L. Gibney’s 60th Infantry Regiment was available to clear the Hürtgen Forest.

Defending the forest at this time, September 1944, was the German 353rd Infantry Division, which had been formed in October 1943 and had fought in Normandy, survivors who broke out of the Faliase Gap with the II Parachute Corps. About half of the division escaped and was immediately assigned to frontline duty in the Hürtgen Forest. To strengthen the weak division, five fortress battalions, an infantry replacement-training regiment, and a Luftwaffe field battalion were attached to the 353rd.

Colonel Gibney had only two battalions available for his attack, and opposition was difficult from the beginning. Every advance by the Americans was met with a rapid counterattack, and on September 20 the Germans were reinforced by an assault gun brigade. Much of the fighting centered on clusters of pillboxes that changed hands repeatedly. By September 20, Gibney saw no prospect of success with his understrength battalions. Two fresh battalions, including one from the 39th Infantry Regiment, took over and made some progress.

The attack cut the Lammersdorf-Hürtgen Road, but it had taken time and significant losses to reach that position. By the end of the month neither the 60th Infantry nor the 39th Infantry were capable of renewing their attack. The 9th Infantry Division halted its attacks. The Hürtgen Forest had claimed its first victim.

The Americans were beginning to discover the secrets of the Hürtgen Forest. It would later be described by writer Ernest Hemingway as “Passchendaele with tree bursts,” a reference to the bloody World War I battlefield. German artillery burst above the ground when it hit the tree tops, showering a deadly rain of shrapnel and splinters upon those below the burst. Visibility was poor, sometimes limited to a few yards.

The forest was constantly wet, either from current rains or moisture retained in the leaf-covered forest floor. Trails were invariably mined, blocked by felled trees, and often covered by enemy automatic weapons. The usual American reliance on armored vehicles was negated by the difficult terrain, mines, and poor visibility. The Germans sheltered in bunkers while the Americans had to advance exposed and with minimal cover from enemy fire. German counterattacks were a regular occurrence.

It was an infantry contest under the worst possible conditions. Even in reserve, one battalion of the 9th Infantry Division lost more than 100 men to German shellfire in a single day.

In early October the bulk of the 353rd Infantry Division was absorbed into Lt. Gen. Hans Schmidt’s recently arrived 275th Infantry Division, although the353rd headquarters units were sent to the rear to reform the division. The 275th Infantry Division had been cobbled together in December 1943 from units destroyed on the Eastern Front. It then fought in Normandy and had been all but destroyed during the American breakout known as Operation Cobra. It fought at Aachen and by October had only 800 men under arms.

Reformed with the absorption of the 353rd Infantry Division’s elements and local defense troops, the 275th numbered 5,000 men with 13 105mm howitzers, one 210mm howitzer, and six assault guns. But when the Americans renewed their attacks in early October, the corps commander, General Erich Straube, ordered the attachment of the artillery from the nearby 89th Infantry Division, an antiaircraft artillery regiment, and a corps artillery group. Two more fortress infantry battalions were also added.

On October 11, 1944, a full-strength regiment, heavily armed with automatic weapons and staffed by officer candidates, arrived to strengthen the defense. General Schmidt planned a major counterattack for the following day. It was largely successful. The 9th Infantry Division’s forward elements were overrun and outflanked, and several hard-won forward positions were lost.

However, communications failed within the German command, and some of the attacking units halted short of their objectives. It took three days for the 9th Division’s 39th Infantry Regiment to recover the lost ground. Once again the battle was hard fought. In one American company, there were only two of four platoons left, one with 12 men and the other with 13.

In one instance, Pfc. James E. Mathews threw himself between his company commander and an ambush, losing his own life but saving his company commander, for which he received a posthumous Distinguished Service Cross.

By the end of October, the 9th Infantry Division’s second attempt at clearing the Hürtgen had failed, although not for lack of trying. Casualties numbered in excess of 4,500 men. For this the division had advanced some 3,000 yards and captured 1,300 prisoners with a further estimated 2,000 enemy killed.

Next into the meat grinder was the 28th Infantry Division. The story of the Pennsylvania National Guard’s infantry division was much the same as that of the Regular Army’s 9th Infantry Division, although on a larger scale. The price the forest exacted from the Pennsylvanians was 6,184 casualties, 16 M10 Tank Destroyers, 31 Sherman medium tanks, and scores of machine guns, antitank guns, mortars, and many other material losses. In exchange, the Germans lost 2,000 killed, 913 taken prisoner, and 15 tanks destroyed.

For reasons never fully explained, the Battle of the Hürtgen Forest continued.

Although there were ways around the forest, allowing it to be outflanked, this was never tried by First U.S. Army commander Lt. Gen. Courtney H. Hodges. Instead, division after division was fed into the furnace only to be wrecked and replaced. Only much later, after the battle, was it put forth that the objective was to reach the critical Roer River dams on the far side of the forest to prevent the Germans from flooding the Roer plain and delaying the planned American thrust to the Rhine River.

The problem with that explanation is simply that there is no mention of the Roer River dams before mid-November—well after the 9th and 28th Infantry Divisions had been through the “hell of the Hürtgen.”

Next into the forest was a portion of the veteran 1st Infantry Division during its operations to seize Aachen. The division’s 26th Infantry Regimental Combat Team entered the forest to clear four hills that dominated the division’s route to Aachen.

Fighting was identical to that of the earlier battles. Trees and undergrowth limited visibility. Mud and inadequate trails slowed progress. Tree bursts were a constant evil. The forest made protecting the flanks of attacking units difficult, and so German counterattacks often hit the 1st with regrettable consequences.

The fighting was exemplified by Pfc. Francis X. McGraw of the 26th Infantry Regiment. A machine gunner, he held off a German counterattack until he ran out of ammunition, then raced back under enemy fire for more. When he returned to his gun, enemy artillery blew a tree down in front of him, blocking his field of fire. Undeterred, Pfc. McGraw left his foxhole and moved his weapon past the log, continuing to fire. A nearby shell burst tossed his gun into the air and knocked him aside. He retrieved the gun and continued to fire until he again ran out of ammunition.

Grabbing an abandoned M-1 carbine, McGraw continued his fight, killing several more Germans before he was himself cut down by an automatic weapon burst. The New Jersey soldier’s Medal of Honor was awarded posthumously.

The next to test the forest was the veteran 4th Infantry Division. Since landing at Utah Beach on D-Day, the division had been in constant combat. Maj. Gen. Raymond O. Barton’s division was to attack to protect the south wing of General Collins’ VII Corps as it rolled toward the Roer River. Its mission was to clear the Hürtgen Forest between Schevenhuette and Hürtgen, then continue on to the Roer south of Düren.

Like the divisions that had preceded it, the 4th suffered heavily in the forest. In addition to the other known difficulties, the division had to absorb numerous replacements while still in combat. Often replacements didn’t even know to which unit they belonged before they became casualties themselves.

In nine days, the 4th’s 12th Infantry Regiment alone suffered 1,600 battle and non-battle casualties. Companies attacking the enemy often found themselves surrounded by other enemy forces that had infiltrated through the thick forest undetected. A regimental commander was relieved. They faced the same adversary—the 275th Infantry Division, now bolstered by some 37 different German units that had been added to the division.

In one instance a platoon leader, 1st Lt. Bernard J. Ray of Company F, 8th Infantry Regiment, had his platoon pinned down by machine-gun, mortar, and artillery fire. The Long Island, New York, officer could not move forward because of a concertina wire barrier placed across his path. The job of blowing up the obstacle seemed impossible due to the heavy and accurate enemy fire covering the wire.

Undaunted, Lieutenant Ray prepared to demolish the obstacle that was exposing his platoon to concentrated fire. He placed explosive caps in his pockets, carried several Bangalore torpedoes, and wrapped a length of highly explosive primer cord around his own body. Despite the intense enemy fire, he crawled forward and prepared the obstacle for demolition. As he did so, he was severely wounded by an enemy mortar round exploding nearby.

Realizing he had only moments to complete his self-imposed mission, Lieutenant Ray wired the explosives to the primer cord still around his own body and pushed down on the charger, destroying himself along with the obstacle that left his platoon exposed to enemy fire. His Medal of Honor was awarded posthumously.

The 4th Division’s 22nd Infantry Regiment didn’t fare any better. In three days of fighting, the regiment had taken 300 battle casualties, including all three battalion commanders, most key staff officers, and half of its company commanders. Forest fighting was hard on leaders who had to expose themselves to select objectives, organize their troops, and communicate with other units.

One such leader was Major George L. Mabry, Jr., a veteran of Utah Beach. He was commanding the 2nd Battalion, 8th Infantry Regiment, on November 20, 1944, when his leading elements were halted by an extensive minefield. Heavy enemy fire covered the minefield, preventing the mines from being lifted. Major Mabry went alone into the minefield and created a safe route through it, all the while under enemy automatic-weapons fire.

He then went ahead of the leading battalion scouts to disable a booby-trapped concertina wire obstacle. After cutting a path through the wire, he moved ahead and observed three enemy soldiers in nearby foxholes. He captured them at bayonet point.

Next, he led the assault against three successive log bunkers from which machine-gun fire was spewing. Then, again leading his battalion from the front, he raced up a hill ahead of the rest of his men to confront nine enemy soldiers who engaged him in hand-to-hand combat. He eliminated two of these before his leading scouts came to the rescue.

Still not done, Mabry led his riflemen in a charge on another bunker in which he captured six more enemy soldiers. After consolidating his gains, he led a renewed assault across 300 yards of fire-swept ground to establish a defensive position on the enemy’s flanks. For his distinguished leadership and personal courage Major Mabry was promoted to lieutenant colonel and received the Medal of Honor.

By mid-November the German command was desperately seeking reinforcements for the seriously depleted 275th Infantry Division. Contingents of the battle-weary 116th Panzer Division were thrown into the fight, but these were too few to make much difference.

By stretching his lines in other sectors, the German Seventh Army’s commander, General Erich Brandenberger, managed to rush the 344th Infantry Division into the forest; it was followed soon after by the 353rd Infantry Division. Neither was at full strength, and both were tired from earlier fighting, but it was all the Germans could provide. The forest ate up infantry equally on both sides.

The failure to clear the Hürtgen Forest worried General Hodges. He ordered his V Corps to move into the forest and take over the assignment while VII Corps moved north, reducing its zone of responsibility. It was hoped that this would bring more power to bear against the remaining enemy strongholds in the forest.

The V Corps commander, Maj. Gen. Leonard T. Gerow, a 1911 graduate of the Virginia Military Academy, had led his corps over Normandy’s beaches, through Paris, and across France into Germany. He brought up the 8th Infantry Division to reduce the zone of the 4th Infantry Division. V Corps would now be responsible for seizing the town of Hürtgen and the Brandenberg-Bergstein ridge, which had stymied VII Corps.

Major General Donald A. Stroh commanded the 8th Infantry Division. He had been commissioned into the Cavalry branch after graduating from Michigan Agricultural College in 1915. He had earlier served with the 85th and 9th Infantry Divisions before receiving command of the 8th (“Golden Arrow”) Infantry Division. The division itself had been fighting since Normandy and had participated in the conquest of the fortified cities of St. Malo and Brest in Brittany before moving east into Germany.

Yet again the forest controlled events. Because of the terrain and defensive responsibilities inherited from the 28th Infantry Division, General Stroh could only deploy one of his three regiments to the main axis of attack.

With two regiments committed to holding the gains made by earlier attacks, only General Stroh’s last arriving regiment, Colonel John R. Jeter’s 121st Infantry, was available to launch the main attack. Even then, the regiment was the last to arrive and had less than a day to prepare to launch the attack over ground they had never seen.

Despite this, Hodges and Gerow had high hopes that a fresh infantry regiment would break the deadlock in the forest and had placed a combat command of the 5th Armored Division in reserve to exploit the expected breakthrough.

The 121st Infantry Regiment launched its attack on November 21, 1944. Before the infantry stepped off, artillery from V Corps, VII Corps, Combat Command Reserve (CCR) of the 5th Armored Division, and the 8th Infantry Division’s own organic artillery pounded the German front lines and villages beyond them. The 8th Infantry Division artillery alone fired some 9,289 shells into the forest, but an attempt to use air support had to be cancelled because of poor weather conditions.

Supported by the entire 12th Engineer (Combat) Battalion and all of the division artillery except the 43rd Field Artillery Battalion, the infantry pushed forward, aided by Company A, 644th Tank Destroyer Battalion and Companies B and C of the 86th Chemical Mortar Battalion. Behind them CCR stood poised to race forward once the infantry had reached the far end of the forest.

The 121st’s three assault battalions immediately ran into strong resistance. Mortar and artillery fire, tree bursts, minefields, and automatic weapons fire from concealed log bunkers slowed the advance. The first day saw minimal progress, and casualties from mines and shrapnel were unusually heavy. The following day, three separate assaults were made by the regiment. Again, progress was limited.

Nevertheless, Company I, 121st Infantry made some 500 yards largely due to the bravery of one of its own noncommissioned officers. Staff Sergeant John W. Minick enlisted from Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and by November 21, 1944, was leading a platoon in Company I. When his company was halted by mines, artillery, and mortar fire, Sergeant Minick led four men through a minefield covered with barbed wire. When he reached the end of the field, some 300 yards ahead of his company, enemy machine-gun fire swept his small group.

Ordering his men to seek cover, Minick edged his way to the flank of the enemy post and opened fire, killing two and capturing three. He continued moving forward and suddenly found himself facing an entire company of enemy infantry. He opened fire, killing 20 and capturing 20 more. His platoon, which had by now caught up, captured the rest of the enemy infantry company.

Sergeant Minick was only getting started. Again moving ahead of his platoon, he encountered another enemy machine gun. He crawled forward until he could knock out the gun and crew. Then his platoon encountered another minefield. Once again, Sergeant Minick led the way, clearing the mines as he went until he stepped on one and was instantly killed. He received a posthumous Medal of Honor.

The next day some light tanks from the 709th Tank Battalion supported the attack but the advance was slow. The aid men and litter bearers of the 8th Medical Battalion were kept busy day and night attending to casualties. Soon Colonel Jeter and one of his battalion commanders were transferred, joining a long list of competent men whose careers were wrecked in the Hürtgen Forest.

Under a new commander, Colonel Thomas J. Cross, the regiment renewed the attack with more tanks from the 709th Tank Battalion. Progress remained slow and deadly, but on November 24 one battalion managed to outflank enemy positions. The news had barely reached Colonel Cross when other reports arrived that the advance company had been hit by a heavy artillery and mortar barrage and been forced back. More commanding officers were relieved of their posts.

The frustratingly slow progress caused General Stroh to call a conference with the commander of CCR, still waiting behind the 8th Infantry Division. Stroh wanted CCR to move up the Germeter-Hürtgen Highway before daylight on November 25 and attack the village of Hürtgen; CCR’s Colonel Glen N. Anderson had reservations.

Although one company of the 121st Infantry had reached the edge of the forest, the Germans still held several hundred yards of the woodline east of the highway. This was a logical hiding place for antitank guns. These would be deadly for the tankers.

Further, since the Germans still covered the road, American combat engineers could not sweep it for mines, including antitank mines. Finally, there was a large bomb crater near the southern edge of the woods that would have to be bridged before the tanks could begin to roll down the highway.

General Stroh ordered his 12th Engineer (Combat) Battalion to bridge the bomb crater. A smoke screen was also ordered to cover the advance of the tanks. As dawn broke on November 25, tanks of the 10th Tank Battalion rolled forward only to find there was no bridge over the bomb hole.

Undeterred, 1st Lt. J.A. Macaulay decided to try and “jump” his tank across the crater. He gathered speed and roared down the muddy road. But the tank fell short, slammed into the far wall of the crater, and fell over on its side, disabled.

Alerted by the sounds of the tanks, the Germans began to shell the road with artillery and mortars; heavy losses were inflicted on CCR’s 47th Armored Infantry Battalion. Meanwhile, in the overturned tank, Lieutenant Macaulay and his gunner, Corporal William S. Hibler, continued firing their 75mm gun at the enemy as best they could.

Troops of the 22nd Armored Engineer Battalion were called up to bridge the crater. Captain Charles Perlman, commanding Company C, was wounded, but his men continued working on the crater. Captain Frank M. Pool, commander of Company B, 10th Tank Battalion took over directing the work but also was soon wounded by German automatic weapons fire. He climbed down from his tank and continued to direct the engineers until he was again wounded, this time by mortars; Lieutenant Lewis R. Rollins took over.

Finally, the crater was bridged. The first tank over the crater, commanded by Sergeant William Hurley, hit a mine and blocked the road. But Staff Sergeant (later Lieutenant) Lawrence Summerfield managed to maneuver his tank around the disabled vehicle and almost reached the bend in the road that led to Hürtgen village.

A German antitank gun opened fire but missed. Summerfield’s gunner, Corporal Benny R. Majka, didn’t, knocking out the gun with his first round. Before the tankers could congratulate themselves, a second German gun fired and knocked out Summerfield’s tank.

The Americans poured more than 15,000 artillery shells into enemy lines, and in a brief break in the weather fighters of the 366th Fighter Group bombed and strafed suspected enemy positions. But CCR’s effort was over. It had lost 150 men in the morning hours of November 25 and had not advanced at all; CCR withdrew to await more favorable circumstances. For the tired infantrymen of the 121st Infantry Regiment, it meant more days in the forbidding forest trying to clear out the stubborn enemy.

General Stroh was determined to finish the job and understood after November 25 that it would have to be done by the foot solders; armor had no place in the deadly forest. The infantry would have to secure the Germeter-Hürtgen road before he would again commit his attached armor.

A look at the situation at the end of November 15, 1944, showed that in fact the 121st Infantry had made some good, if difficult, progress. Most of the best defensive lines in the forest had by now been overcome, leaving the Germans with less in the way of good positions from which to contest the American advance.

To the 8th Division’s north, the 4th Division had made good progress as well and outflanked many of the German positions holding back the Golden Arrow boys.

General Stroh stretched his division’s lines in order to release another battalion to add strength to his next attack. This freed up Lt. Col. Morris J. Keesee’s 1st Battalion, 13th Infantry to be attached to Colonel Cross’ 121st Infantry.

The new plan was for Colonel Keesee to circle around behind the German flank, passing through the zone of the 4th Infantry Division, and strike from the unexpected direction, perhaps unhinging the entire German defense. Once again the objective was the village of Hürtgen.

On November 26, while waiting for Colonel Keesee’s battalion to get into position, the 121st Infantry renewed its attack. The results were astounding. Other than the expected mines, shelling, and the occasional straggler, opposition had disappeared. The Germans had withdrawn from this sector of the woods. Before noon that day the infantrymen were looking down on the village of Hürtgen.

Colonel Cross ordered an immediate attack on the village, a primary objective of the battle. Conflicting reports from patrols indicated either that the village was abandoned or that it was strongly held.

By dark, Company F, 121st Infantry had reached a position 300 yards southwest of the village. Here it was halted by heavy machine-gun fire and stopped for the night. The following day, Company F led the regimental attack. Protected by massive divisional artillery fire aided by the guns of Company C, 644th Tank Destroyer Battalion, Lt. Col. Roy Hogan’s 3rd Battalion, 121st Infantry cleared the woods.

Alongside, the 2nd Battalion and tanks of the 709th Tank Battalion reached the southern edge of the village. Colonel Keesee’s battalion moved northwest of the town under a heavy enemy artillery barrage. That evening patrols again reported the town as abandoned.

The morning of November 28 saw Companies A and B, 13th Infantry, supported by Company A, 644th Tank Destroyer Battalion, seized the Kleinhau-Germeter road. But once again reports that Hürtgen was abandoned proved inaccurate. As the 121st Infantry advanced on the town from the west and south, it was stopped by heavy machine-gun fire. Colonel Cross halted the attack, reorganized, and launched a new attack to address the strong defenses.

This new attack by the 2nd Battalion, 121st Infantry, and Company C, 13th Infantry, supported by the 709th Tank Battalion, finally overran Hürtgen. More than 350 prisoners were taken, and bodies of both American and German soldiers littered the streets of the much fought over town. The expected counterattack came late in the afternoon but was repulsed with heavy losses to the enemy.

General Stroh now alerted Colonel Glen Anderson at CCR. He was to move to Hürtgen and be prepared to launch an attack on the town of Kleinhau and the high ground around around it. In the meantime, the 3rd Battalion, 121st Infantry would finish clearing the woods around Hürtgen. Coordination between CCR’s attack on Kleinhau and an attack on Brandenberg by the 3rd Battalion, 28th Infantry and the 121st Infantry was also established.

Task Force Hamberg of CCR made the attack on Kleinhau. The task force, under the command of Lt. Col. William A. Hamberg, commanding officer of the 10th Tank Battalion, who led Company C of his battalion along with Company C of the 47th Armored Infantry Battalion forward early on November 29.

The leading platoon, under Lieutenant Robert C. Leas, moved off the road to provide flank protection and immediately had four tanks stuck in the mud. But the following platoons ran straight up the road to the village. Lieutenant T.A. McGuire and Lieutenant George Kleinsteiber’s platoons had, by mid-morning, entered the village. Supported by the 95th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, the task force was soon fighting within the village. Additional tanks and infantry arrived from other task forces of CCR.

A single Mark IV German tank knocked out one American tank before it was itself destroyed. An antitank gun hidden in the woods outside the village was similarly disposed of by the Shermans of Task Force Hamberg. Outposts were established near, but not on, Hill 401.3.

By nightfall CCR was able to turn the town over to elements of the 8th Infantry Division. The cost was eight tanks destroyed, mostly due to mines, 13 half-tracks and a tank destroyer of the 628th Tank Destroyer Battalion badly damaged, and 60 armored infantry casualties. Overall, the fight for Hürtgen and Kleinhau had cost the 121st Infantry and 1st Battalion, 13th Infantry some 1,247 casualties. The Germans lost 882 men captured alone.

Behind the lines, command of the Golden Arrow Division changed hands. General Stroh had been overseas since the early days of North Africa in 1942. He had witnessed the death of his son who had been shot down while flying a fighter-bomber in direct support of his father’s 8th Infantry Division. He was overdue for a rest. He was ordered to the United States for that rest under the condition that he return and command another division once he was sufficiently refreshed. The Golden Arrows’ new commander was Brig. Gen. William G. Weaver.

Born in Louisville, Kentucky, General Weaver was commissioned into the infantry from West Point in 1912 and served in France during World War I. He had been the assistant division commander of the 90th Infantry Division before assuming command of the 8th. Among his decorations were three Distinguished Service Crosses and three Purple Hearts. Once in command, General Weaver quickly learned that despite all the earlier talk about Hürtgen, the seizure of that village was not the end of the battle. The forest was awaiting more victims.

General Hodges wanted possession of the Brandenberg-Berstein Ridge, for now First U.S. Army understood the importance of the Roer River dams and wanted a launching position for a direct attack on them. In turn, the Hürtgen-Kleinhau position was the best available for an attack on the ridge. A highway ran along the ridge between the woods on either side. Gerow ordered Weaver to use his 28th and 121st Infantry Regiments to clear the corridor while the 13th Infantry Regiment held the Hürtgen-Kleinhau area. CCR of the 5th Armored Division remained attached to Weaver’s division.

It took until December 1 for the infantry to clear the approach for the armor to begin an attack along the highway. Once again the difficulties were the same: mines, log bunkers, barbed wire, automatic weapons, and artillery fire.

Finally, the way was clear for Task Force Hamberg to run down the road. Again, lead tanks were knocked out by mines and antitank weapons. Automatic weapons and mortar fire halted the armored infantrymen. General Weaver sent his own men forward to clear some enemy-held areas that had remained hidden earlier, while the armored engineers cleared the road of mines.

By December 3, elements of the 28th Infantry and 121st Infantry, supported by tanks of the 709th Tank Battalion, had reached the ridge. On that day, the weather finally cleared and, with the welcome support of Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighter bombers of the 366th Group, Task Force Hamberg once again rolled down the highway.

With this combination, American tanks advanced on Brandenberg shortly after breakfast. So strong was the attack that Lieutenant Kleinsteiber rolled past the town and halfway to Bergstein, where he knocked out two antitank guns, before Colonel Hamberg called him back. Although he planned to take both villages in one attack, the colonel realized he did not have sufficient strength to hold them both should the enemy inevitably counterattack.

As if to remind Colonel Hamberg of his weakness, American planes had to return to base due to weather conditions there, and about 60 German Messerschmitt Me-109 fighters arrived and began attacking his task force. Several were shot down by CCR and 8th Infantry Division antiaircraft units.

Another of Colonel Hamberg’s worries was the German observation from Hill 400.5, known as Castle Hill to the Americans and the Burg-Burg to the Germans. Enemy shelling directed from there was causing considerable difficulties for Task Force Hamberg. With only 11 tanks, five tank destroyers, and 140 infantrymen left to him, Hamberg was anxious about his ability to hold his gains.

Meanwhile, General Weaver was anxious to attack Bergstein. He ordered a renewed attack, which Colonel Anderson launched with CCR on the afternoon of December 4. CCR secured the town by nightfall. Once there, guns on Castle Hill again threatened their safety. In addition to the observed artillery fire, the town itself was open to attack from all sides. Indeed, on December 5 the enemy launched three strong counterattacks that struck the 3rd Battalion, 28th Infantry, whose defensive stand earned it a Presidential Unit Citation.

Indeed, German commanders were concerned about CCR’s penetration of the ridge; they brought up additional troops from the 47th and 272nd Volksgrenadier Divisions for a counterattack. Although neither unit was at full strength, they posed a significant force against a weakened CCR.

The first German reinforcements arrived on December 6, and the counterattacks began immediately, supported by five armored vehicles and dozens of antitank teams. But, despite a strong attack and a near German success, CCR and the 28th Infantry held Bergstein.

But Castle Hill still pounded the Americans in and around Bergstein. Two more German counterattacks were launched from its vicinity, supported by artillery fire controlled from its heights. CCR was becoming progressively weaker, and General Weaver had no more infantry left to strengthen it. He appealed to V Corps for assistance, specifically for the 2nd Ranger Battalion, which was nearby but under V Corps control.

Companies D, E, and F of the 2nd Ranger Battalion gained eternal fame when on D-Day they climbed the sheer cliffs of Pointe du Hoc to knock out German guns that threatened the Omaha Beach landings. The Rangers atop the cliffs fought off strong German counterattacks for two days before being relieved. Losses were heavy, and the battalion spent the next several weeks training replacements.

Next the battalion, under Lt. Col. James Rudder, was assigned to protect the flank of the 29th Infantry Division during the struggle for Brest in Brittany. The Rangers seized the Lochrist (Graf Spee) Battery position on September 8 and took 1,800 prisoners. The Rangers then moved east through Paris and camped for additional training in the Hürtgen Forest, where General Weaver found them on December 6, 1944.

The battalion was rushed forward on December 7 to the outskirts of Bergstein, arriving in the early morning hours. Just as the battalion left its bivouac area, Colonel Rudder departed to assume command of the 28th Division’s 109th Infantry Regiment. Major George S. Williams, the Ranger battalion’s executive officer, assumed command of the battalion; the decision to relieve Rudder was not a popular move. One of the Ranger officers said, “It was something of a low blow to George because he knew it was going to be a bad fight and you don’t always change command in the middle of an operation.”

But the battalion had confidence in Williams, who had just been promoted to major, and he led it toward Castle Hill.

As they moved, the Rangers improved everyone’s morale. One member of the 47th Armored Infantry Battalion later wrote, “About midnight a guy came down the road, then two others, each one five yards behind the other. They were three Ranger lieutenants. They asked for the enemy positions and the road to take; said they were ready to go. We talked the situation over with the officers. They stepped out and said, ‘Let’s go men.’ We heard the tommy guns click and, without a word, the Rangers moved out. Our morale went up in a hurry.”

Major Williams had two assignments. He was to seize Castle Hill and strengthen the defense of Bergstein. To achieve the second, he established roadblocks to the west, east and south of Bergstein, strengthened by platoons of the 893rd Tank Destroyer Battalion.

Defending Castle Hill was Captain Adolf Thomae’s 2nd Battalion, 980th Grenadier Regiment of the 272nd Volksgrenadier Division, with 36 pieces of artillery on call. Against this defense Major Williams sent D and F Companies.

The Ranger scouts moved forward, ignoring challenges they thought were in English, and suddenly found themselves in the German front lines. Behind them Captain Duke Slater formed D, E, and F Companies and launched the assault. Led by E Company, the Rangers caught the Germans by surprise as they thought the scouts who had pulled back were the only threat.

Artillery fire began to strike among the Rangers, but D and F Companies pushed past E Company and continued the attack. Below, outside Bergstein, Companies A, B, and C observed self-propelled German artillery moving forward. A call to CCR put an end to that threat.

Captain Mort McBride’s D Company and Captain Otto Masny’s F Company now faced an open field that they had to cross to reach the main German positions. Closely behind a rolling artillery barrage, the Rangers charged Castle Hill with fixed bayonets. Several machine guns and a bunker blocked the way.

Lieutenant Lem Lomell led the D Company assault, losing some men but gaining the top of the hill. So quickly did the Rangers move that some charged past the hill and were on their way to the Roer River before Lomell called them back.

Captain Thomae had planned for such an eventuality. Preplanned artillery now began to hit Castle Hill in increasing ferocity. Neither courage nor skill helped a soldier in such a situation. As Lieutenant Lomell commented, “It was a matter of luck.”

The Rangers finished clearing the hill and took what cover they could find in the German fortifications. Casualties had been heavy, but the Rangers remained atop the hill for two more days, being attacked five times by strong German forces, including paratroopers. One Ranger company was commanded by a sergeant, as all officers and higher noncommissioned officers had become casualties.

Finally, late on December 8, the 1st Battalion, 13th Infantry relieved the Rangers. Only 22 Rangers were still able to walk off the hill under their own power. The Rangers had suffered 19 killed, 107 wounded, and four men missing—one of every four Rangers who made the initial attack. But from Castle Hill the Americans could see the town of Schmidt, the Roer River, and the Roer River Dams.

The Hürtgen Forest had finally claimed its last victims.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments