by Mike Haskew

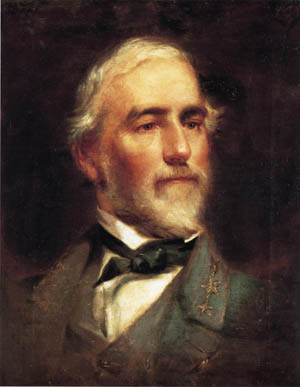

When the Civil War broke out, Robert E. Lee of Virginia was offered command of the Union army. Born at Stratford Hall, Virginia, on January 19, 1807, the son of famed Revolutionary War soldier Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, III, he had served in the U.S. Army since graduating from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point at the top of his class in 1829. Lee led the contingent of U.S. troops that captured radical abolitionist John Brown at Harpers Ferry in 1859.

[text_ad]

Joining the Confederate Army

However, when Virginia seceded from the Union, Lee chose to resign his commission in the U.S. Army and cast his lot with the Confederacy. Following the wounding of General Joseph E. Johnston during the Seven Days Battles in the spring of 1862, Lee was elevated to command the Confederate force that became known as the Army of Northern Virginia. Lee is remembered for his daring and audacious command of the primary Confederate fighting force in the Eastern theater of the Civil War.

Lee’s Legacy at Chancellorsville and the Battle of Gettysburg

Twice during the war, Lee defied military convention and divided his army in the face of a numerically superior foe. His army was saved at Antietam in September 1862, by the timely arrival of General A.P. Hill’s Light Division, ending his first invasion of the North. At Chancellorsville in May 1863, the Army of Northern Virginia won a great victory as Stonewall Jackson led his detached corps against the Union flank.

Some historians have criticized Lee’s tactical decisions at the decisive Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, as Lee attacked the Union Army of the Potomac, which held commanding positions along high ground. Lee chose to attack rather than maneuver, and his second invasion of the North ended in defeat as the might of Confederate arms reached its proverbial “high tide.”

On the Defensive After Gettysburg

During 1864-65, Lee was forced to fight a defensive war, attempting to safeguard the Confederate capital at Richmond, and he came finally to the realization that the war of attrition was one that he could not win. Facing the overwhelming superiority of Union men and equipment, Lee’s army suffered irreplaceable losses during campaigns in Virginia. He was forced from his entrenchments before Petersburg and Richmond and pursued to Appomattox Court House, where he surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant, commander of all Union armies in the field, on April 9, 1865.

After the war, Lee became president of Washington College in Lexington, Virginia. He died of a stroke on October 12, 1870, and the institution was subsequently renamed Washington and Lee University. Following his death, Lee’s stature among military commanders of the Civil War grew tremendously, and today he remains an iconic figure of the conflict.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments