By Roy Morris Jr.

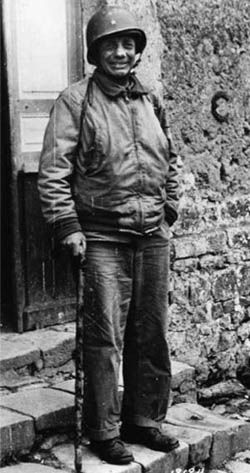

Bobbing alongside his troops in a wildly careening LCVP, Theodore Roosevelt Jr. gripped the walking cane he used to get around on his bum left knee—the unwelcome souvenir of the first Great War, after receiving a German machine-gun bullet taken near Soissons in July 1918. He was also using the cane to fend off the well-intentioned assistance of one of his men as they got ready to jump into the landing craft 11 miles from the French coast. “Get the hell out of my way,” he growled good-naturedly. “I can jump in here by myself. I can take it as well as any of you.” No one who knew “Ted” Roosevelt could ever doubt the truth of that statement. At 57, he was the oldest man in the entire D-Day Invasion, now in the midst of storming ashore on the northern coast of France in the greatest amphibious assault in military history. He was also the only general to personally hit the beach on D-Day.

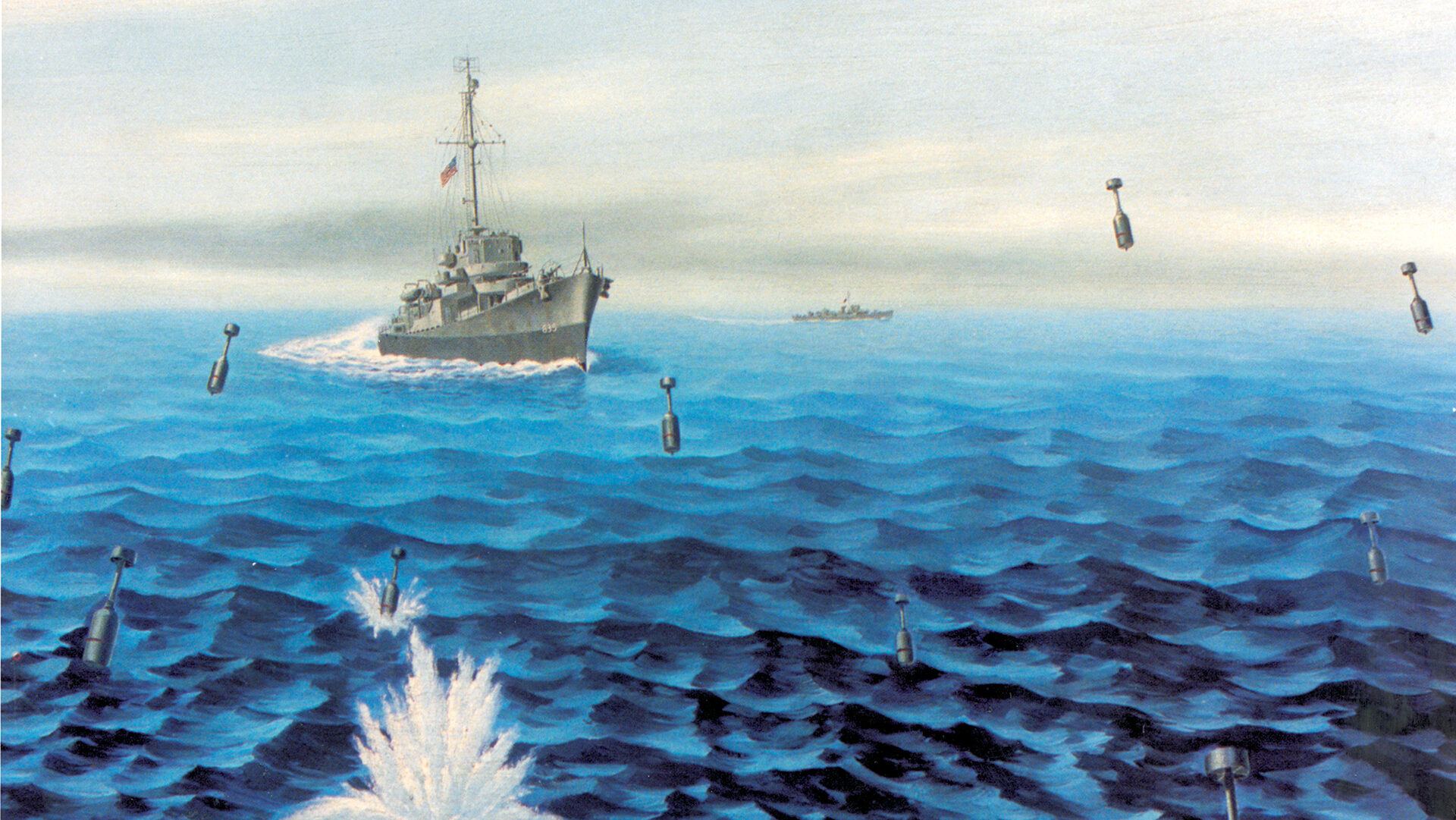

A hundred yards from the sandy stretch designated as Utah Beach, Roosevelt dropped into the water, walking stick in one hand and silver-plated .45-caliber pistol in the other. Like his father in Cuba, Roosevelt had finally reached his “crowded hour.” And it would be a fateful moment for both the general and his troops. Coming ashore with the 4th Infantry, a fortuitous combination of unforeseen circumstances—the loss of control vessels to guide the assault, a thick cloud of smoke from supporting Allied naval fire, and a strong tidal current sweeping everything to the west—had forced the division’s 20 LCVPs over a mile south of their original objective. Roosevelt immediately recognized the error. He located Captain Howard Lees of E Company, 2nd Battalion, 8th Infantry, and crouched at the top of a sand dune with his men.

“Hey, this doesn’t look like what they showed us,” Lees said, referring to the tabletop model the officers had trained on back in England. Roosevelt told him to sit tight and calmly walked back to the beach to reorient himself. Sand showered down on Roosevelt from artillery explosions, but he only brushed the dirt impatiently from his shoulders and kept walking. One shell, landing uncomfortably close by, caught a group of American soldiers broadside as they were wading ashore. Putting his arm around one man’s shoulders, Roosevelt said gently, “son, I think we’ll get you back on a boat.”

While still under fire, Roosevelt, Commodore James Arnold, Colonel James Van Fleet and Cols’ Conrad Simmons and Carlton MacNeely held a hasty council of war in Arnold’s foxhole. Roosevelt made a quick decision about what to do, and he made it without hesitation. “I’m going ahead with the troops,” he said. “Get word to the Navy and bring them in. We’ll start the war from here.” It was a statement that would later make Roosevelt famous. For the time being, though, he began organizing the drive, and, continuing to exhibit total disregard for his own safety, Roosevelt paced back and forth from seawall to surf, grabbing officers and enlisted men and heading them in the right direction.

So how did Roosevelt and the 4th do at their impromptu invasion point? Their performance “was remarkable,” Major General Thomas Handy reported. “It was a new division that had never been blooded. We all though Utah was going to be more of a problem that Omaha—the damned terrain swampy with causeways; one gun at each could stop tanks from coming through.” The Germans never got the chance, because Roosevelt never gave them time to stop him. True to his word, he had started the war when and where he wanted. Because he did, the Allies made their first crucial lodgment on French land.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments