by Roy Morris Jr.

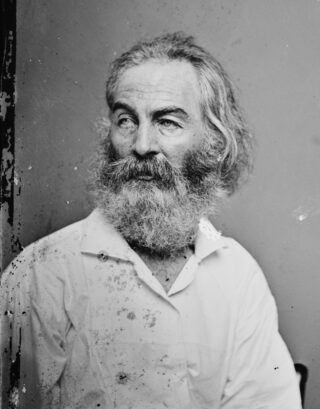

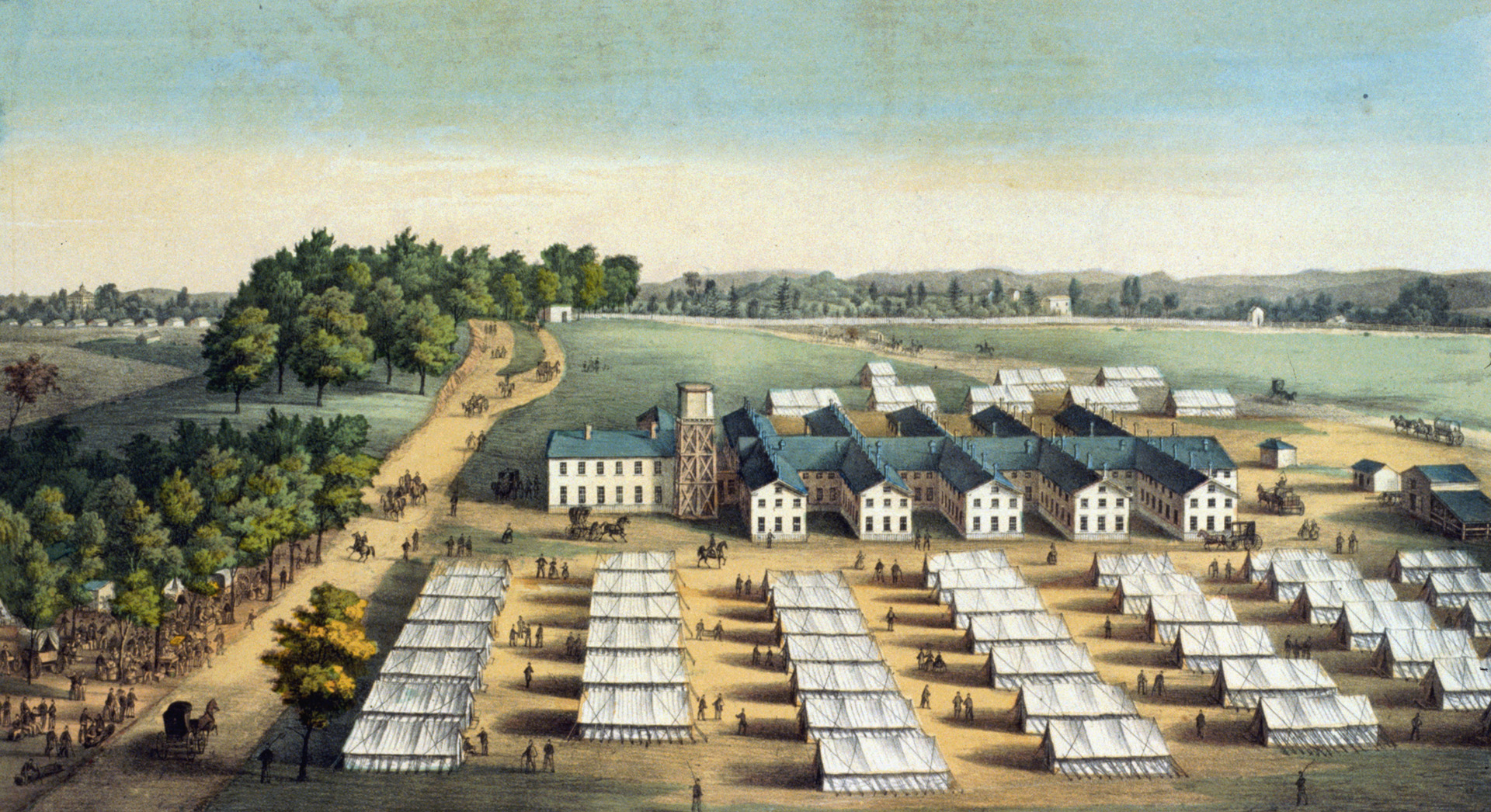

Walt Whitman did not play favorites while visiting his “boys” in the Union hospitals during the Civil War. Each of the soldiers he spoke to on his self-appointed rounds got a few ungrudging minutes of his time. He shared with them all a kind word, a smile, and more often than not a small gift of some sort—anything to make their stay in the hospital a little less grueling. They were all, he said, “the real precious & royal ones of this land.” Inevitably, there were a few soldiers who stood out from the rest. One was 19-year-old Erastus Haskell, a fifer with Company K, 141st New York Volunteers. Haskell, suffering from a fatal case of typhoid at Armory Square Hospital, impressed Whitman with his fine manners and humble, uncomplaining nature. “I am not much of a player yet,” he confessed. Sadly, he would never get the chance to improve. Two weeks after Whitman met him, Haskell died.

In a remarkably kind letter to the young man’s parents in Breesport, New York, Whitman described their son’s last moments. “He was a quiet young man, behaved always correct & decent, said little,” Whitman wrote. “I used to sit on the side of his bed—I said once, You don’t talk any, Erastus, you leave me to do all the talking—he only answered quietly, I was never much of a talker. He had large clear eyes, they seemed to talk better than words. I do not know his past life, but what I do know, & what I saw of him, he was a noble boy. I think you have reason to be proud of such a son, & all his relatives have cause to treasure his memory.”

“You must not forget me, for I shall never forget you.”

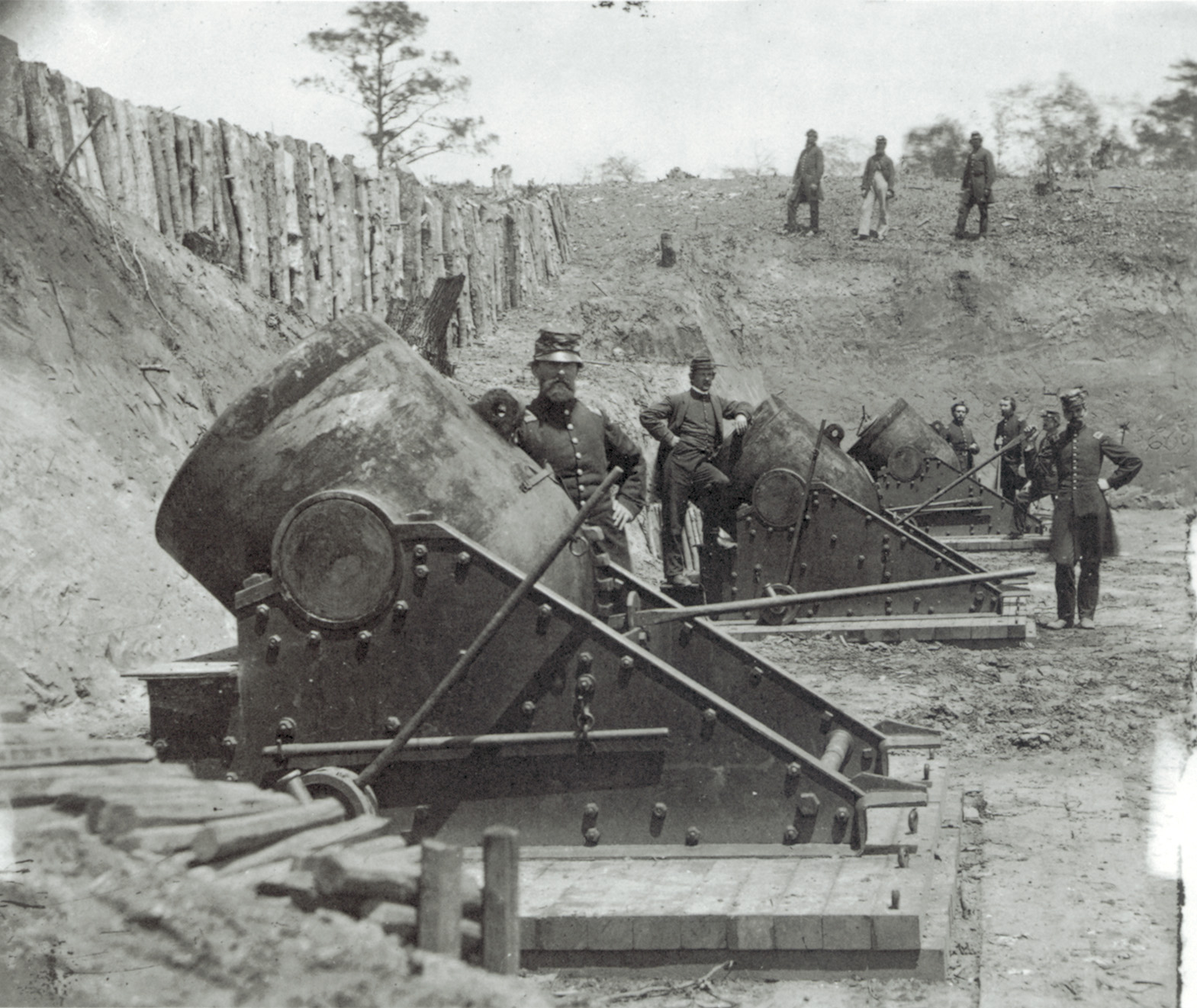

Two other soldiers, in particular, laid claim to Whitman’s heart: Lewis Brown and Thomas Sawyer. “Lewy” Brown, an 18-year-old native of Elkton, Maryland, had been badly wounded at the Battle of Rappahannock Station in August 1862, when a Confederate shell shattered his left leg. Whitman met him at Armory Square Hospital and personally witnessed the subsequent amputation of Brown’s leg. The youth had modest plans, Whitman observed: “Go to school, learn to write better, learn a little bookkeeping so that he can be fit for light employment.” It took six months for

Brown to recover, during which time Whitman sat with him through many long nights. Years later, Brown still remembered Whitman’s kindness. “There is many a soldier now that never thinks of you but with emotions of greatest gratitude,” he wrote to the poet, “and I know that the soldiers that you have been so kind to have a great big warm place in their heart for you. I never think of you but it makes my heart glad to think that I have been permitted to know one so good.” A friend of Brown’s, 21-year-old Cambridgeport, Massachusetts, soapmaker Thomas Sawyer, had been wounded 10 days after Brown at the Second Battle of Manassas. A member of the 11th Massachusetts Infantry, he recovered more quickly than Brown and returned to his regiment, but not before capturing, probably unintentionally, Whitman’s fervid affection. “You must not forget me,” Whitman wrote to Sawyer at the front, “for I shall never forget you. My love you have in life or death forever.” Sawyer, more taciturn than Brown, responded somewhat formally, “I fully reciprocate your friendship as expressed in your letter and it will afford me great pleasure to meet you after the war will have terminated or sooner if circumstances permit.” In the end, Whitman never reunited with Brown or Sawyer, but he never forgot them either—or the thousands of their fellow sufferers he had met during the war. In one of his last poems, Whitman wrote of them all: “The moon gives you light,/And the bugles and the drums give you music,/And my heart, O my soldiers, my veterans,/My heart gives you love.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments