By Roy Morris Jr.

It was unseasonably warm in Charleston when the Democratic National Convention opened for business at noon on April 23, 1860. Thin columns of steam rose from the cobblestone street outside the South Carolina Institute Hall, where 606 delegates from across the country were gathering to select their party’s next presidential candidate. A brief midmorning shower did nothing to lower the sweltering heat, and the doors and windows of the two-story wooden building were thrown open in a vain attempt to create a cross breeze in the jam-packed first-floor assembly room. Early-arriving delegates swished palm-leaf fans, mopped their necks with balled-up handkerchiefs, and squirmed in their hard-backed chairs like restless children in Sunday school. The deafening rattle of horse-drawn carriages on Meeting Street drowned out the opening remarks by executive committee chairman Daniel Smalley and local minister Christian Hankle. Onlookers in the overhanging balconies added to the general hubbub on the convention floor. Nobody in the hall could hear himself think.

By any objective measure, Charleston was a disastrous choice for the Democratic convention. Not only was it difficult to reach by rail—an exhausting 13 train changes were required between Washington, D.C., and the Carolina coast—but local hotels were unable to handle the onslaught of delegates. Several delegations chartered boats to use as floating dormitories, while others planned to pitch tents on public property—a plan that local authorities quickly quashed. Many Democrats, particularly those from northern states, opted not to attend the convention at all. Said one disgusted Chicago delegate, “Charleston is the last place on God’s earth where a national convention should have been held.” Another added that he had “never been taught to believe in eternal punishment,” but that the 13-hour train ride had caused him to change his mind.

The putative nominee of the party, Illinois senator Stephen Douglas, did not share his supporters’ doubts. Against all evidence to the contrary, Douglas still hoped that southern delegates would reconsider their fierce opposition to his candidacy and rally to his cause. Given the growing strength of the northern-based Republican Party, Douglas contended that he was the Democrats’ last, best hope to stave off disaster at the polls in November. “There will be no serious difficulty in the South,” Douglas assured New York supporter Peter Cagger a few days before the convention. “The last few weeks have worked a perfect revolution in that section.”

The Kansas-Nebraska Act

Events would soon prove Douglas wrong, with disastrous results for both his own political aspirations and the nation’s continued well-being. In Charleston, convention delegates quickly deadlocked on the choice of a Democratic candidate for president. Douglas, who had narrowly missed winning the party’s nomination in both 1852 and 1856, was by far the strongest candidate, but his authorship of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which called for “popular sovereignty” in all new territories, had seriously weakened him in the eyes of southerners. His subsequent opposition to a pro-slavery state government in violence-plagued Kansas further hardened southern resolve. On the eve of the Charleston convention, newspapers throughout the South denounced Douglas in unequivocal terms. “The demagogue of Illinois deserves to perish upon the gibbet of Democratic condemnation,” wrote one Alabama newspaper, “and his loathsome carcass to be cast at the gate of the Federal City.” The Jackson Mississippian concurred, calling Stephen Douglas “the most profligate of all political reprobates, a turbulent demagogue and a miserable thimble-rigger with a remarkable capacity to betray.”

Douglas, of course, did not see it that way. To his way of thinking, the Kansas-Nebraska Act had been a wise and courageous effort to bridge the ever-widening gap between the North and the South. The cause of that gap, as always, was slavery—or more accurately, the expansion of slavery into new territories. Nearly a decade and half after the overwhelming United States victory in the Mexican War, the nation was bitterly torn over the issue of whether the South’s “peculiar institution” would be allowed to spread into other parts of the ever-expanding country. To increasingly embattled southerners, this was an absolute necessity; political strength in Congress and the various state legislatures was tilting ever northward. Soon, southerners worried, lawmakers would vote to limit—or even outlaw—slavery. Douglas, perhaps the shrewdest politician in the nation during the fractious decade of the 1850s, thought he had devised a way to bridge the gap between the regions. Popular sovereignty, the right of local residents to decide whether or not to allow slavery in their territories, would take the power out of the hands of national politicians and give it back to the people themselves. Who could argue with that?

As it turned out, many of his fellow Americans could. Much to Douglas’s chagrin, the new law pleased no one in either region of the country. In newly created Kansas Territory, pro- and antislavery zealots rushed in to tilt the odds in their side’s favor. Half a decade of unprecedented political bloodshed followed, and “Bleeding Kansas” became a textbook example of the law of unintended consequences. Not only did the violence there worsen the regional divide over the issue of slavery, but it also hastened the demise of the Whig Party, whose northern and southern wings could not reconcile their differing views on slavery.

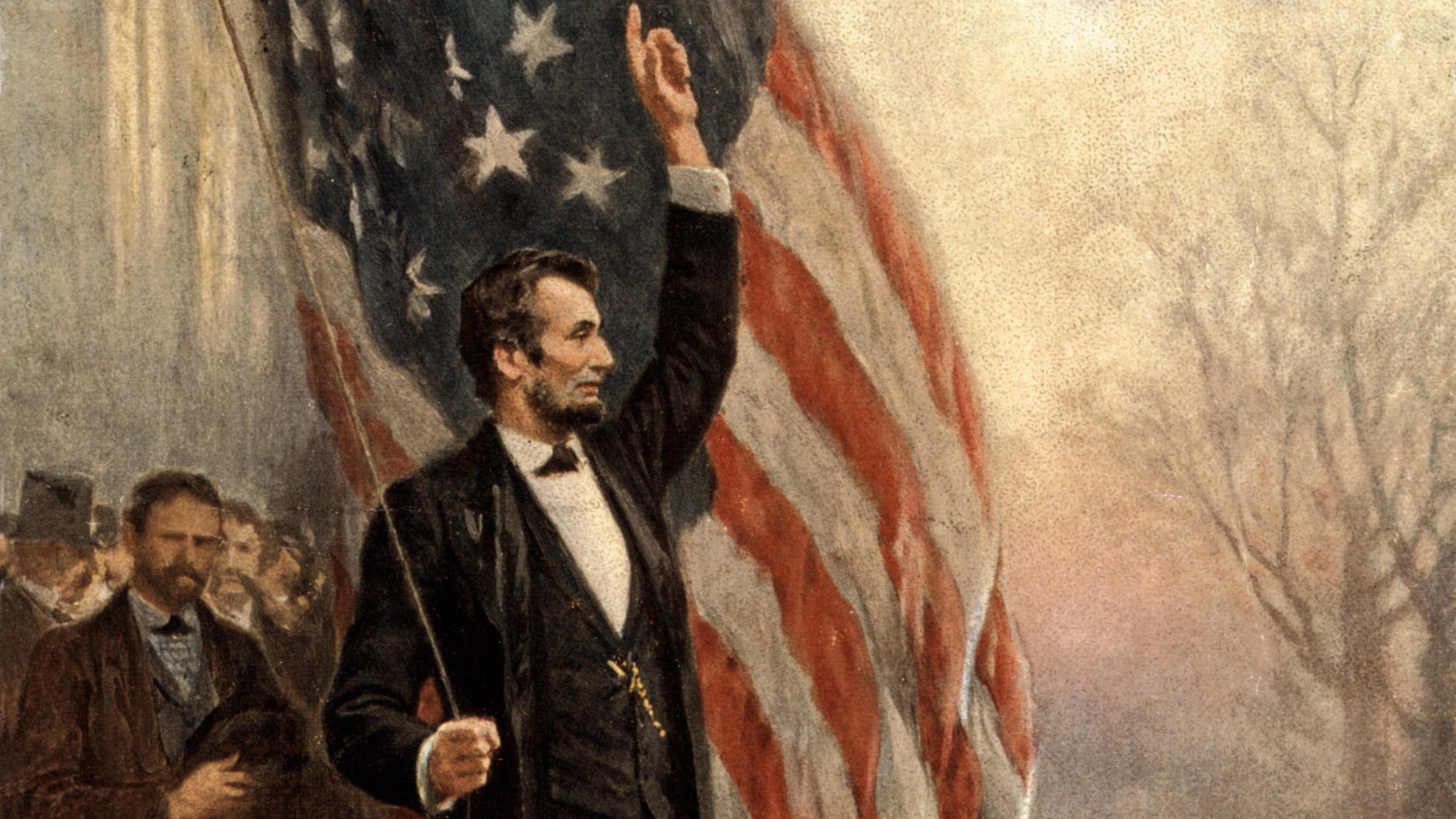

The sudden wreck of the Whigs, the only viable alternative to Stephen Douglas’s Democratic Party, empowered the development of a new political party based solely in the northern half of the country and brought out of retirement an old and bitter enemy of Douglas—a fellow Illinois politician named Abraham Lincoln. As a one-term Whig congressman, Lincoln had opposed the war with Mexico and the subsequent spread of slavery into newly acquired territories. This opposition had cost Lincoln his seat in Congress and seemingly ended his political career. But the uproar over the Kansas-Nebraska Act brought Lincoln back into politics, and his highly publicized senatorial race against Douglas in 1858, although it ended in failure at the ballot box, had vaulted Lincoln into national prominence as one of the most eloquent and thoughtful spokesmen for the antislavery cause.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments