By Tim Miller

Early in June 1940, refugees from northern France and the low Countries who had flooded Paris in May fled with the residents of the city as the German advance neared. To save the City of Light from destruction, however, at the last moment Paris was declared an open city. The Germans marched in unopposed on June 15.

Five days later, in the distant village of Vicq-sur-Breuil, Agnès Humbert, an art historian and one of the millions of refugees on the road, happened to hear General Charles de Gaulle’s famous address to the French people from London. While hardly anyone knew who de Gaulle was, and while those who did called him a crackpot, Humbert was immediately jolted out of her despair over the fall of France. In her diary for the day she wrote, “I feel I have come back to life…. He has given me hope, and nothing in the world can extinguish that hope now.”

That same day she had somehow come across a fellow scholar on the road, Jean Cassou, also in his early 40s. Together they had witnessed the death of a 16-year-old girl run over by a fleeing French Army truck; help from a passing medic only did so much, and Humbert wrote of her and Cassou, “This half hour together at the side of a dying girl has bound us to each other with deep bonds of comradeship. We both know it.” A month later, still on the road, Humbert noted with joy the news that German posters put up in Paris were constantly being torn down. “The people of Paris are rebelling already,” she wrote, and she decided to return to the city and do the same.

By early August she was back, and so was Cassou. After exchanging some pleasantries, both found themselves expressing the same desire. Humbert told Cassou, “I feel I will go mad, literally, if I don’t do something…. The only remedy is for us to act together, to form a group of 10 like-minded comrades, no more. To meet on agreed days, to write and distribute pamphlets and tracts, and to share summaries of French radio broadcasts from London.” Admitting to herself that neither they or their colleagues were quite spymaster material and were unlikely to succeed on any practical level, nevertheless, “simply talking about our ‘organization’ makes us feel better.”

It did not take long to gather a handful of like-minded individuals under the slightly overblown name of The Free French of France (Les Français Libres de France), and while the group’s intelligence activities did reveal their inexperience it would be wrong to say they had no experience whatsoever. Nearly all of them had already acted in some way on behalf of the Spanish Republic against Franco’s fascists. Humbert herself was as much a scholar as a political activist, having both written a monograph on Jacques-Louis David, a renowned artist of the French Revolutionary period, and contributed articles to The Worker’s Life (La Vie Ouvrière) under a pen name.

It took less than two months for their first pamphlet, Vichy Wages War, to appear. It was a response to the Vichy government’s decision to fire on Free French forces in Dakar in the French colony of Senegal. Suddenly, there it was in the Métro, in post offices, and even mixed in among the clothing for sale in department stores. Stickers declaring support for General de Gaulle also began to show up in phone booths, on the walls of the Métro, and in public urinals (she later hope that de Gaulle would “forgive his humble servants their ignominious means.”)

Humbert’s group had been inspired in part by an anonymous pamphlet that had appeared in August, 33 Hints to the Occupied (33 Con- seils á l’occupé), a kind of guide for conscientious passive resistance. For example, in response to the obnoxious sight of German soldiers wandering the capital with guides and French phrasebooks, it says, “Every one of them has his little camera screwed to his eye. But have no illusions: these are not tourists.” Parisians needed reminding of this because of how disturbingly easy “normal” life had reinstated itself under occupation. The Paris Opera reopened in late August with the same program from when it had closed in June, while the Louvre reopened in September. A columnist begged his readers to withhold judgment—especially if it was being made in the Free Zone—and asked what was wrong with trying “to forget our sorrows, and their piteous burden, by going to see a show”? The ease with which cultural life continued seemed to have even surprised Hitler, but it was considered a boon if the citizens of Paris wanted to keep themselves entertained, the Führer saying, “Let’s let them degenerate. All the better for us.”

From then on, the question of what constituted “collaboration” would exercise the minds of many. Should one not attend, let alone write, direct, or perform in, an opera, play, movie, or cabaret in which Germans were present or involved? Were the major literary magazines and publishers, such as the Nouvelle Revue Française and Gallimard, right to keep some semblance of themselves alive by continuing to publish, albeit now under Nazi censors? Did the then-unknown author Albert Camus act in the wrong by agreeing to remove foot- notes mentioning the Jewish author Franz Kafka, simply in the desire to get real ideas out in occupied Paris? Was collaboration with the one hand justified if it meant access to influence and power which, with the other hand, could undermine that very collaboration?

After the war it was noted how collaborationist writers and artists had been condemned much more roundly than, say, the French workers for Renault, who manufactured tanks for the Wehrmacht. However, Humbert and her group, and later the more militant Resistance, seem to have understood that this was only true for so long. After all, Paris was not known for the beauty of its automobiles or the genius of its factories, but for its culture, and it was the subversion and perversion of that culture in the country’s capital that was a symbol for how far France had fallen. Witnessing the reorganization of museum libraries, now filled with German authors and their dubious racial theories and their lecture halls now filled with the same, and with the occupying force ordered to be (for now) as gracious as possible, Humbert and Cassou saw the occupation not as a threat France’s physical life, but to her soul.

Before Vichy relieved her of her job, Humbert had been an employee of the museum of French popular and folk art, the Musée National des Arts et Traditions Populaires, and by the autumn of 1940 she had come into contact with a clandestine organization centered around the neighboring anthropology museum, the Museum of Man (Musée de l’Homme. Both museums were housed in the Palais de Chaillot, built in 1937 to coincide with the World’s Fair held in Paris that year. More organized and with a wider network of contacts than the Free French, in time all of them came to live under the umbrella of what was later called the Musée de l’Homme Group.

Nearest to Humbert was the leader of the Musée de l’Homme Group, linguist and ethnologist Boris Vildé, who had already served in the French Army, been imprisoned by the Germans, and escaped; Christiane Desroches, Egyptologist at the Louvre; Anatole Lewitsky, Yvonne Oddon, and Jacqueline Bordelet, all three employed by the Musée de l’Homme; 18-year-old René Sénéchal, known affectionately as “The Kid”; a handful of other librarians, translators, lawyers, journalists, accountants, concierges, nurses, pharmacists, and other friends who listened nonstop to BBC broadcasts from London, by then an illegal act in Paris, or who helped distribute the group’s publications.

At times Humbert admitted the precariousness of their situation. “Here we are, most of us on the wrong side of 40, carrying along like stu- dents all fired up with passion and fervor.” She also noted the strangeness of following de Gaulle, since no one in the group had even seen a picture of him, which was quite a contrast to the ubiquitous presence of Hitler’s portraits in Germany, or now of Vichy leader Philippe Pétain’s portraits in France. Humbert had the feeling of following “an unknown figure,” but they persisted and in October and November also began taking in downed British and Polish pilots and helping usher them out of France to Portugal and Britain. Even Humbert’s ill and aging mother was fearless and unquestioning that she and her daughter would take these men in. Humbert no doubt thought of her two grown sons in taking the men in; at the time her son Pierre was still in the south of France with the others in exodus, while her other son, Jean, was in Newfoundland with French naval personnel.

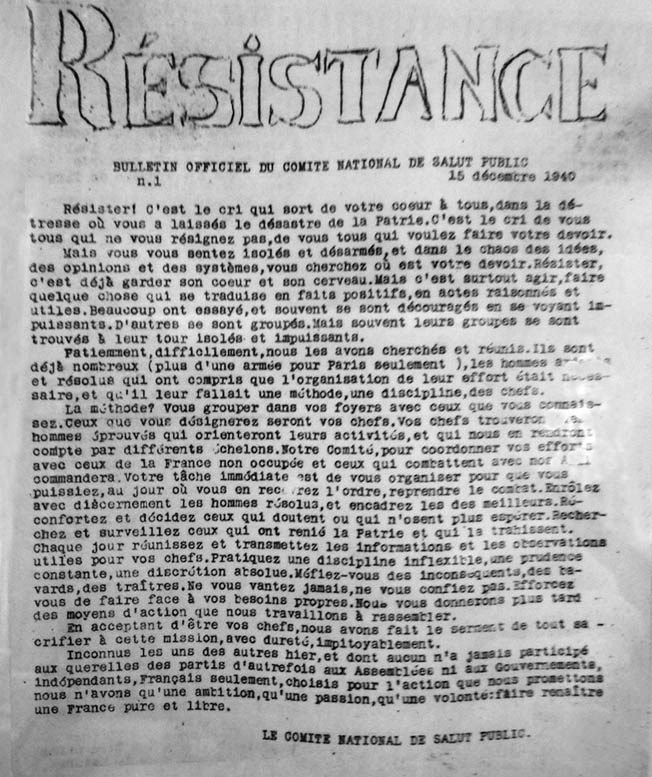

In late November they finally had an actual newspaper in the works. Originally titled Libération, the name was rightly assumed a bit premature, and it was rechristened Résistance. Published on December 15, it contained what amounted to counterintelligence gathered from radio broadcasts, foreign newspapers obtained from the American embassy, and other outlets. By then the “legitimate media” had merely become an arm for Germany propaganda, and a later member of the French Resistance, Claude Aveline, described the importance of Résistance as “a true account of the latest news, explanations as necessary, acts of defiance and rallying calls, every possible reason for retaining an absolutely unshakeable hope and optimism.”

And optimism is what Boris Vildé’s editorial in the first issue hoped to instill. No doubt it had the same effect as de Gaulle’s radio broadcast had for Humbert: “Give heart and resolve to those beset by doubt and those who no longer dare to hope. Track down and watch those who have disowned their country and who betray her.”

Addressing the isolation many like-minded French people must have felt, Vildé encouraged individuals and groups to mobilize together and coordinate in order “to act, to do something that translates into positive actions, into calculated and positive actions…. Meet up every day to pass on information and observations that may be useful to your leaders…. Beware of those who are reckless or feckless, loose- tongued or treacherous. Be neither boastful nor too trusting.”

It is in this context that Humbert began to see the danger her group was in. Given the opportunity of being the go-between for maps and other intelligence to be supplied by an air force veteran from World War I, Humbert initially exulted, “At last! Now I can see an opportunity to do something more than propa- ganda!” However, she reflected “As a direct result of my meddling, people—French people, living peaceful lives—will be killed and wounded, children maimed. Where are all my lofty humanitarian ideals now…? How could I ever have wanted to be involved in such a filthy business?”

Determined to refuse the offer, she suddenly came upon the indignity of three French porters, in the dead of winter, trudging along in the slush with the luggage of two German soldiers. At this sight Humbert’s mind was made up again, and for good, and her words remained as brutal and pragmatic a statement as any to come from a mere “civilian” during the war. “We simply have to stop them. We can’t allow them to colonize us, to carry off all our goods on the backs of our men while they stroll along, arms swinging, faces wreathed in smiles…. And to stop it happening we have to kill. Kill like wild beasts, kill to survive. Kill by stealth, kill by treachery, kill with premeditation, kill the innocent. It has to be done, and I will do it.”

Yet by this time the group’s inexperience was beginning to show. In trying to convince the friend who would supply her with the important maps, Humbert had mentioned the better known Jean Cassou by name and then naïvely remarked, “Too bad, his name is out of the bag—but for a catch like this it’s worth it!”

Indeed, it was not until February of the next year, well after the group had been infiltrated by the Gestapo, that they realized they all needed to adopt code names. And it was almost maddening to read her remark, only a month before her own arrest, “Besides, why would anyone be interested in me? I’ve done so little and been so careful.” Because, as valuable a document as her diary was, its very existence (and its free use of real names) showed just how incautious she really was.

Meanwhile, Jean Cassou’s wife chided their plans at raising money “as though we are a couple of children playing at shops.” Another member was so brazen as to wander the mar- kets and shove leaflets into the baskets of housewives, a tactic she was merely teased about. Humbert herself, saying no one would destroy a bank note these days, wrote “Vive le Général de Gaulle” on five franc bills. And more than a few times she mentioned that their clandestine meetings—until the end nearly always held at the same location—at times devolved more into reminiscing than getting on with the business at hand.

The specter of arrest and prison always loomed large in their minds, no matter how they tried to laugh its eventuality off. In mid- February, dozens of employees from the Musée de l’Homme had been arrested and questioned as the museum itself was raided, while those not yet detained attempted to flee and reach the Free Zone. During March, the Kid, who by this time had been going back and forth to Toulouse, passing documents to the British and trying to find printers for Résistance, whose fifth and final issue appeared that month, also disappeared. Others in the group believed they were being followed. One of the first to disappear was Boris Vildé, arrested on March 26.

Humbert herself refused to go to the Free Zone because she could not abandon her ailing mother. The Gestapo took no such considerations into account, and by the middle of April she was arrested as well. Arriving at her home, the Gestapo upended everything, confiscating her typewriter and even looking for secrets in the extendable dining room table. While they did come across an unfinished front page for Résistance, it was so incomplete that she could plausibly claim it was part of a personal project and nothing more. As she later noted, however, they never did find “the Résistance file, with its 400 names and addresses, lying quietly hidden—together with copies of all the tracts we had published since September 1940—under the stair carpet between two floors.”

Not that the Gestapo didn’t have other information to draw on, and not that this delayed her arrest at all. Once at police headquarters, she caught sight of Vildé, already much thinner and finding it difficult to walk. “Our eyes meet,” she wrote, “and he gives me a long look of inexpressible sadness. A look that will haunt me forever.” Her interrogator later asked her with a grin, “He’s changed a bit since he’s been with us, don’t you think?”

In only a few months, 19 members of the group were arrested by the Gestapo. And yet it grew and changed to meet whatever demands occupied Paris required. In August of that year they assassinated a German naval cadet in the Métro. In October, Boris Vildé said from prison, “I love life, God, I love life. But I’m not afraid of dying. To be shot would in a sense be the logical conclusion to my life.”

It took a few months, and despite the attempted intervention of the writers François Mauriac, Paul Valéry, and Georges Duhamel, Vildé and seven others were executed on February 23, 1942. Humbert was spared the death penalty but sentenced to forced labor and was incarcerated in a succession of prisons until late March 1942, when she was transferred to Anrath prison in Germany, and finally the Phrix rayon factory in Krefeld, where she and other underfed female prisoners worked under horrible conditions, daily exposed to chemical injury with no protection. Humbert mentions burns, boils, abscesses, ulcers, temporary blindness from acid vapors, “and other suppurating wounds of mysterious origins.” There was more than one suicide among the women in the factory. In 1945, Humbert was liberated by American forces and immediately set about assisting in their hunt for fugitive Nazis.

At least one member of the Musée de l’Homme group, the African ethnologist Deborah Lifchitz, died in Auschwitz. Others ended up in London and worked with Gaullist groups and British intelligence later in the war. Jean Cassou was able to escape to Toulouse and avoid capture in early 1941, but was finally arrested in December. While incarcerated, he composed his famous 33 Sonnets Composed in Secret (33 Sonnets composés au Secret) in his head. It was published under a pseudonym in 1944. Released from prison in 1943, he continued his resistance activities in North Africa and Toulouse.

In 1944, he was attacked by Germans the day Toulouse was liberated and spent nearly a month in a coma. When he woke, de Gaulle was at his bedside, no longer a faceless voice or even a venerated photograph, and awarded him the Croix de la Libération. After the war he was appointed director of the National Museum of Modern Art and died in 1986.

Later recalling her imprisonment and forced labor at the rayon factory, Agnès Humbert wrote of one evening among many when she and another woman were trying to push a cart, whose wheels were unoiled, through the factory. “I push so hard that I fall flat on my face,” she wrote. “Furiously I said to myself: ‘In 50 years’ time my family will know how I was treated by the Germans. I have a grandson, Yves. He will tell his children how I was forced to work beyond the limits of human endurance.’”

Many later members of the Resistance testified to the importance of the work Humbert had done, so even lacking her own diary and memoir she would have been remembered. One of these Resistance members was Germaine Tillion, who spoke with admiration for these early resisters: “Small, autonomous entities [which] multiplied like microbes in tropical waters,” so soon after the fall of France, and how like crystals, each group, each individual, illuminated and reflected all the others.

This was all Humbert seems to have wanted, after all. Demoralized in the south of France after fleeing Paris, disgusted at the sight of German soldiers on her train back to the capital, and mortified at how life seemed to have picked up where it left off despite the daily German marches down the Champs Elysees, despite having to change all of their clocks to Berlin time, despite coming upon French prisoners of war herded down the streets of Paris like animals, all she wanted was her country back.

On June12, 1945, she finally got it. Hidden with a handful of others in the back of an American Army truck, she felt that simply by passing a few words with the cheerful French driver that she was already in Paris again. The night was a fitful one, and she felt every bump and jostle along the way until finally, ruminating over all that had happened and swirling around every thought in her head, she wrote: “In my profound philosophizing the driver lifts the corner of the tarpaulin, sticks his head through, and shouts: ‘Allez, on your feet, you lot! Jump to it—we’re in France!’”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments