By Stephen D. Lutz

On August 2, 1945, two weeks prior to Japan’s surrender, the highest ranking Japanese officer captured during the war in the Pacific was taken on the island of Morotai, Dutch New Guinea. What makes that event remarkable is the fact that those who captured him were members of the 93rd Infantry Division, 25th Infantry Regiment. Of the division’s 14,000 members, well over 90 percent were African Americans. The 93rd’s story is one of overcoming obstacles. Most military units only need to battle the enemy; the 93rd had to battle hatred and discrimination at home, a white-dominated military establishment that didn’t want them, and officers that didn’t want to lead them. Worst of all, the 93rd had to fight the widespread belief that the black soldiers in WWII were not capable of performing with exemplary courage on the battlefield.

The 93rd Infantry Division got its start as an all-black outfit during World War I and proved its mettle in ferocious battles in France. However, apprehensions existed as to what to expect from 20,000 armed African Americans concentrated in one place. The most overriding questions were how well they would fight—or if they would fight. How well would they follow their white officers in combat?

At first, thousands of 93rd soldiers found themselves doing nothing more than manual labor within the Army. For whatever reason, the segregated, white-dominated U.S. Army thought of the 93rd the way the British and French thought of American soldiers overall. Could any American, regardless of color, fight and succeed in a European war?

Upon arrival in France, the American Expeditionary Force itself was almost parceled out to serve under British and French command structures, but General John J. Pershing said no. (Actually, some units did serve under the British, and black American units were under French command.)

After proving itself, the U.S. Army was still in a quandary about what to do with the 93rd. Black officers were generally regarded as incompetent, and no white officer wanted the command.

The French had no such hesitation. They readily welcomed the 93rd but assigned its four regiments to three French divisions. The 369th Regiment went to the 161st Division, the 370th Regiment went to 26th Division, and the 371st and 372nd Regiments went to the 157th (Colonial) Division.

From that point on the only American thing those four regiments did was wear American uniforms. They ate French rations, used French weapons, fought using French military tactics, and probably learned to speak quite a bit of French.

Although their uniforms were American, their helmets were the French-style, blueish-tinted Adrian helmet. The 93rd’s division patch, henceforth, became the silhouetted Adrian helmet patch in a black circle. Because of this, the 93rd was nicknamed the “Blue Helmet” Division.

Throughout World War I, no other American division had as many days in continuous direct combat as those of the four regiments constituting the 93rd. The 369th notched 191 days, beating any similar white unit by a week. The men were decorated with the French Croix de Guerre to show that they had proved their capabilities; 23 years after World War I, the 93rd would have to go through it all over again.

The Two Black Divisions of World War II

During World War II, the U.S. Army fielded 68 infantry divisions; the normal number of soldiers hovered between 14,000 and 18,000 per division. By early December 1941, the African American press, along with some of their white counterparts, was campaigning to expand the participation of blacks in the war expected to come.

In turn, the U.S. Army clearly stated its position on racial integration. Social integration was a civilian-sociological activity to figure out. It was never meant to be a military issue. In regard to the anticipated war, the Army first envisioned four all-black divisions, but in the end only half came to be. One division—the 92nd—wound up in Italy, while the other—the 93rd—served in the Pacific Theater.

Another division, which would have been designated the 2nd Cavalry Division, got as far as Oran, Algeria, on March 9, 1944. Once there, it was broken up and divvied out in parcels as support units to larger operations and mostly in noncombat roles. It would be up to the 92nd and 93rd to show what the African American infantry soldier was capable of doing.

The Black Units of Fort Huachuca

Although there were black units that fought in the American Revolutionary War and in the Civil War, the modern era of African American soldiers began in 1892. Fort Huachuca, Arizona, lies in the state’s south central region of the Sierra Vista mountain range within 20 miles of the Mexican border. Historically, Fort Huachuca was a western frontier fort positioned for intervening with renegade Indians and roaming bandits, whether Mexican or American.

The first Army unit billeted at the desolate post was the 24th Infantry Regiment (Colored) in 1892. Then came the 25th Infantry, followed by the 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments; all four were African American, or “colored” units. By 1939 the primary residents at Fort Huachuca were the 10th Cavalry and the 25th Infantry. By the time the 93rd was activated there for its military training on May 15, 1942, the educators/drill sergeants were be those from the 24th Infantry Regiment.

As a pre-World War II military installation, Fort Huachuca’s populace rarely rose above 800, but that number was about to expand greatly. Fort Huachuca was such a remote, out-of-the-way setting it seemed a perfect place for African American units, for the Army believed there would be less racial friction with any nearby civilian populace. The Army was wrong; fights––often deadly—between black and white soldiers and the civilians were a common occurrence.

Like all the Army posts of the day, Fort Huachuca was segregated, even when it came to medical care. Two hospitals existed—one strictly for white patients and the other for black. The latter hospital had nearly 950 patient beds, making it America’s largest African American hospital staffed by all African American medical personnel.

Of course, there were also separate barracks, mess halls, and service clubs for officers, noncommissioned officers, and enlisted ranks of both races. Soldiers in the 93rd also brought with them just over 900 dependents: wives, children, and even a few parents.

There were complaints aplenty. One soldier in the 369th told a visiting black general, “I’m basically fighting against slavery down here, sir,” while another said, “The Jim-Crowing of our outfit down here must stop.”

Generals Charles P. Hall and William Spence

While the enlisted men were black, most of the officers were white, and it was generally thought that being assigned to command a black unit was the “kiss of death” for a white officer. Appointed division commander was 55-year-old, 1911 West Point graduate and veteran of the 2nd Infantry Division in World War I Maj. Gen. Charles P. Hall.

Hall was the first of four commanders during the 93rd’s nearly four-year existence. It was his task to lead the 93rd through its 17 weeks of basic training, then any advanced training required—a task most of his contemporaries did not envy.

One of the reasons Hall was selected was because he had been born and raised in Mississippi. Because he had come from the Deep South, many of his military superiors thought he could relate to African American soldiers better than others considered for the job. Again, the Army was wrong.

The 93rd’s Division Artillery commander, Brig. Gen. William Spence, was another Southerner who had a North Carolina upbringing and thus got his assignment under the same circumstances.

Hall’s newly formed division consisted mostly of 14,000 enlisted men within the ranks. Among its 883 officers—about half of whom were black—were first and second lieutenants. When one new black lieutenant reported to his white company commander, the captain did not even return the younger officer’s salute; “I hate ni–ers,” is all the captain said.

The 93rd Infantry Division’s Conversion to a Triangular Division

Before the outbreak of World War II, the U.S. Army revised its organizational structure to the “triangular” concept, meaning that a division had three regiments as compared to the four during World War I. With this streamlined concept, the 93rd Division now had three regiments: the 25th, 368th, and 369th. While the 25th had previously existed as a Regular Army regiment, the 368th was originally the 8th Infantry Regiment of the Illinois Army National Guard; the newly formed 369th was composed mostly of draftees. Each regiment had three battalions.

Brigadier General Spence’s field artillery had four battalions: the 593rd, 594th, 595th, and 596th, each with 12 guns (primarily 105mm howitzers). Additionally there were the 93rd Quartermaster Battalion, 318th Engineer Combat Battalion, 318th Medical Battalion, 793rd Light Maintenance Ordnance Company, 93rd Signal Company, 93rd Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop, a military police platoon, and other support units.

In terms of personnel, the Blue Helmet Division resembled just about any other infantry division on paper—60 percent draftees, 26 percent volunteers, and 14 percent transferred veterans.

In keeping with the Army’s standardized instruction schedule, the 93rd’s first 17 weeks of training included the basics of soldiering—learning how to march, perform the manual of arms and close-order drill, adjust to barracks life and military discipline, etc. Then came 13 weeks of training in infantry, artillery, or other specialties.

Once proficiency was achieved, the division was graded and moved up to the level of a “maneuver” division. That meant a 14-week encounter with other divisions in staged war games. Following that came the final eight weeks of specialized training that focused on where the selected division might be headed.

A Lack of Educated Soldiers

From the beginning the 93rd was burdened with the trials and tribulations of discrimination. The Army’s inductee test for military capabilities was heavily skewed against black soldiers in general and the 93rd in particular. The Army General Classification Test (AGCT) set the standard for what direction any recruit would go during his Army career. The basics of that test measured one’s level of reading and comprehension. Thus Class 1 represented the highest scores; Class 5 was the lowest.

It seemed that the 93rd was doomed before even progressing beyond its basic training, for most of its members had received a substandard education. Of the 14,000 men within the 93rd, only 0.1 percent reached Class 1, while 45 percent of the division was rated Class 5. Within white divisions of the same experience, 6.6 percent were rated Class 1 and 8.5 percent were at Class 5.

These prejudices even affected the division’s 585 black lieutenants. To be a commissioned officer, one either had to have a college degree (which few blacks had at the time) or had graduated from Officers Candidate School (OCS). The higher ranking black officers—captains and majors—were mostly found among the medical or chaplain corps. Once such officers showed an exceptional degree of leadership and education and were skilled enough for advancement, many were transferred out.

As for their white counterparts assigned to the 93rd, some being West Point graduates, those lieutenants resented their assignment; many could not get transferred away from Fort Huachuca quickly enough. Thus, keeping qualified, competent junior officer leadership in the 93rd became a challenge.

The Army wasn’t the only institution with a “race problem.” The Marines did not accept African Americans, and the Navy accepted almost none between the world wars; in the late 1930s, blacks could join the Navy but could serve only as mess stewards.

Once war broke out, the American Negro press, along with some progressive white newspapers, began to point out that blacks were not given a fair shake by the military, especially considering deficiencies in Negro education. One argument involved how well educated the typical Russian peasant-soldier holding the Nazi advance at bay in Western Russia was. Nobody really knew how educated the typical Japanese soldier in the Pacific was, but he was fighting extremely well.

“Blue Army” vs “Red Army”

In October 1942, Maj. Gen. Hall, the 93rd’s commander, was “bumped upstairs” and replaced by Maj. Gen. Fred W. Miller. His direct instruction to his staff was to minimize the duties and responsibilities of the division’s black soldiers.

At one point men of the 93rd wanted to change their division patch from the French Adrian helmet silhouette to something more American. One idea kicked around was a rattlesnake since they were plentiful around their Arizona home. Another was an outline of the State of Arizona.

In a division-wide vote, the majority opted for a growling black panther. The division’s executive officer, Brig. Gen. Allison J. Barnett, also voted his approval on the black panther symbol but higher headquarters overruled the vote, insisting that the Adrian helmet remain to designate the division’s World War I lineage.

The 93rd began its 17-week basic training program in the Arizona heat. Then came the interdivisional 13-week coordinated unit sessions. Then Arizona governor Sidney Osborn had a less-than-brilliant idea. When the division was not training, perhaps it could be used to pick the cotton in Pima and Maricopa Counties since many of the able-bodied field hands were off in military service or war industries.

While President Roosevelt thought the idea had merit, it was eventually quashed. As one sociologist said, “The armed forces should bend over backwards to see that Negro soldiers are not the first soldiers to be used as farmers and that of all things they should not be assigned to pick cotton which epitomizes to many a return to slavery status.”

After receiving the minimum basic training, then taking part in interdivisional war games, the 93rd departed on April 3, 1943, for the large-scale 1943 Louisiana Maneuvers. During that time the other black division, the 92nd, moved into the vacated Fort Huachuca.

For three months the “Blue Army” and “Red Army” chased each other across swamps, up and down hills, and through towns. There was much animosity between white units and the 93rd, and fights often erupted. If the military police got involved, it was assumed that the 93rd “started it all” and received punitive actions at some level. A point came when 125 soldiers within the 93rd collected more than 100 rifles and hid them for any unexpected racial shootout. Fortunately, that did not happen.

Umpires judged every aspect of the maneuvers. According to the 93rd Division’s commander, Maj. Gen. Fred W. Miller, the 93rd did rather well—nothing too exceptional, nothing too exceptionally poor. The Third Army commander, Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger, agreed the 93rd was well led and performed adequately. America’s then-highest-ranking African American general, Brig. Gen. Benjamin Davis, Sr., also praised the 93rd’s performance. The 93rd had one more go-around before proving itself prepared for overseas movement.

Sending the 93rd Infantry Division to War

The 93rd moved west into the Southern California Mojave Desert Training Center that butted up against western Arizona. This range, covering 18,000 square miles, was used for the final training of divisions prior to being shipped overseas.

Within this desert training area were a number of camps. The 93rd moved into a camp built just for their convenience at Charleston, Arizona, specially established to be a segregated camp.

For months the 93rd was led to believe it was being prepared for desert warfare while what many thought was a high-level conspiracy was in play. America’s top officer, Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall, was never a supporter of an integrated army.

A step below Marshall was Lt. Gen. Lesley J. McNair, commander of Army Ground Forces. This 61-year-old, 1904 West Point graduate had the next to the last word on whether or not Army units were ready for combat operations. His preference was to see African American divisions broken up and no more than regimental-sized sub-units be parceled out to other units. Almost to a man, American military leaders were dubious of what any sizable African American infantry unit could achieve.

Farther down the chain of command was 59-year-old 1912 West Point graduate Lt. Gen. Millard F. Harmon. In 1916 he was among the first Army Air Corps pilots. By late January 1942, he was chief of staff of the Army Air Forces and ended up managing the Army’s ground war operations across the South Pacific while the 93rd was still training in the Mojave Desert. In early 1944, he told his superiors he needed another infantry division, and its color made no difference to him.

At this time, Douglas MacArthur was coming under fire from his boss, President Franklin D. Roosevelt. As commander in chief, Roosevelt was pressured into answering more and more inquiries from the African American (and white) press: Why weren’t more black combat units in the war? By January 1944 it was settled: The 93rd Division would be going off to war.

Menial Labor and Chores

The 93rd was put on troop trains heading to California. Just east of San Francisco was the city of Pittsburg with its bustling Camp Stoneman Replacement Depot. Once there, the 93rd learned that it was headed not for the desert but to the Pacific Theater. Leading them was their new commander, 48-year-old Maj. Gen. Raymond G. Lehman of Minnesota, a World War I veteran. Under intense pressure back home for the commitment of black troops to combat, the 93rd would soon ship out for Guadalcanal.

In February and March 1944, elements of the 93rd began arriving on Guadalcanal, where major fighting had ended more than a year earlier. But there still were scattered remnants of Japanese resisters who could make life interesting for the Americans.

No sooner had the 93rd arrived on Guadalcanal than it was disassembled and its various parts were shipped to other locations under XIV Corps commander Maj. Gen. Oscar W. Griswold.

Remaining on Guadalcanal were the 25th Infantry Regiment, one field artillery battalion, and a section from the medical battalion. The 368th Infantry Regiment, 594th Field Artillery Battalion and another group of medical personnel ended up at Banika in the Russell Islands. The 369th Infantry Regiment, 595th Field Artillery Battalion, and other selected groups landed in the New Georgia Island group. Other elements of the 93rd were sent to Wake Island where there was little combat.

A separate all-black regiment, the 24th—with whom the 93rd Division had shared space at Fort Huachuca—had been on Guadalcanal since August 1943. Most of the black troops were relegated to service duties such as improving bivouac areas, building roadways, or working as stevedores—dockworkers unloading and reloading ships. If time permitted once their chores were done, the 24th joined with the 25th Infantry Regiment for brief courses in jungle fighting and survival.

As for the 25th, they, too, were given little to do but hard, menial labor and guard duty along the perimeter of their bivouac areas at night with a rare foray into the jungle on combat patrols. Intermittent Japanese air raids provided the only excitement.

The black troops were told the same story by the Army: The manual jobs they were performing were a necessity and would keep them physically fit for actual combat. But the 93rd despaired of ever seeing combat; it remained a scattered, disjointed division for nearly 14 months. Their “baptism of fire” would come on Bougainville, a part of the Solomon Islands.

First Fight at Bougainville

The fight for Bougainville had been taking place sporadically since November 1, 1943, against Japanese soldiers who hid out in the jungle after first fighting against the U.S. Marine Corps’ 3rd Division.

On January 12, 1944, the Army’s 23rd Infantry Division, also known as the Americal Division, took over from the Marines. In late March 1944, the 25th Infantry Regiment was sent from Guadalcanal to Empress Augusta Bay on the southern end of Bougainville to join Americal’s three regiments—the 164th, 182nd, and 132nd.

Each battalion of the 25th would be attached to an Americal regiment and given more extensive schooling in jungle warfare. The terrain and climate were a far cry from the California desert in which the unit had previously trained.

Also there was the 1st Battalion of the 24th Regiment, attached to the 132nd.

Based out of a bivouac area just off the Torokina Airstrip, the three battalions of the 25th Regiment commenced field operations with their Americal counterparts from squad- to platoon- to company-size patrols. Later, many of the 25th veterans would vividly recall the stench of rotting jungle vegetation and decaying animals and humans.

Many a wounded or ill Japanese soldier who was not able to keep up with his comrades would climb a banyan tree and tie himself to it. Essentially he became a sniper locked in place and attached to the tree. Even if not shooting an American, many snipers would die in those trees without being discovered.

Eased into combat, the 25th soon found its footing and began to perform like a seasoned unit. On March 31, during attacks on Hills 500 and 501, Private James H. O’Banner became the first enlisted man of the 93rd Division to kill an enemy soldier.

A Chaotic Patrol

The worst day for the 25th Regiment on Bougainville was April 7, 1944. On that day 180 soldiers of the 3rd Battalion’s Company K followed their white captain, James J. Curran, on a special patrol. This particular adventure was the 25th’s first company-size operation almost entirely on its own.

It was viewed as such a major step forward for the regiment, if not for the 93rd Division as well, that two Army Signal Corps photographers went along to document the event.

Another “guest” was Captain William A. Crutcher as artillery spotter from the 93rd’s 593rd Field Artillery. Of this entire lot of 180 men, only one was an experienced combat veteran—the white Sergeant Ralph Brodin of the Americal’s 164th Regiment.

The mission focused on blocking a trail lying 3,000 yards beyond Americal’s perimeter. It was a path long recognized as being used by the Japanese. Expecting to encounter some of the enemy, Curran’s company went out well prepared. Nine BAR (Browning Automatic Rifle) men were a part of the patrol, along with four .30-caliber machine guns, one 60mm mortar, and two SCR-300 radios.

Setting out on the morning of April 6, Curran advanced his company with the first platoon as point. The second platoon was divided between the two flanks. The third platoon, led by the company’s second in command, black Lieutenant Oscar Davenport, brought up the rear.

Reaching a point about 2,000 yards from their line of departure, Company K found an abandoned enemy aid station. After securing the find, Curran had the first platoon split into “finger patrols” and move farther forward. Within minutes enemy fire was received. Then it all dissolved into chaos.

Survivors would claim at least three enemy killed in that initial exchange of gunfire during which the three platoons commenced firing in every direction. The jungle vegetation was so thick and heavily overgrown that the three platoons could not see one another, let alone at whom they were shooting or from where the shooting was coming.

Curran radioed battalion commander Colonel Everett M. Yon for instructions and was told to reel in his company, fall back 300 yards, regroup, and make a more coordinated advance. That, however, would never happen. Some Japanese were yelling out orders in English that some of Company K thought were legitimate “cease-fire” orders.

One Company K soldier, James Graham, said he shot a Japanese soldier up close and hit him dead center of his chest. The dying Japanese soldier said in coherent English, “You got me.”

Lieutenant Davenport went forward in an attempt to regain order at the center of the firing, only to be killed when he paused to help a wounded comrade; nine others were also killed. Survivors of the skirmish would testify that the only strong, standout person throughout the 40-minute firefight was Sergeant Ralph Brodin, who went about rallying soldiers and pointing them in the right direction to either shoot or withdraw. He constantly exposed himself to enemy fire and somehow was physically unscathed by it all.

The men of Company K then realized that Captain Curran, his radioman, and the company’s first sergeant were nowhere to be found. By then Captain Crutcher was calling in a spot-on artillery concentration, and the 593rd dropped two dozen rounds on what was believed to be the enemy’s concentrated gathering site.

By 5:30 pm survivors brought back 20 wounded, leaving 10 comrades dead where they fell. If not for Sergeant Brodin’s cool leadership, those numbers would have ballooned. Also left behind were one radio, one machine gun, one mortar with all its rounds, 18 M-1 rifles, and three carbines, plus a considerable amount of discarded personal equipment. The Signal Corps photographers never took a single picture, or at least none that were ever made public.

Investigating the Catastrophe

Between April 14 and May 2, 1944, the Americal Division conducted what it thought was a thorough, fair, unbiased, nonbigoted investigation into the debacle. Upon testimony of the survivors it was ascertained that Company K came up against no more than two dozen enemy soldiers, and Captain Curran apparently fled the field of battle with the first sergeant hot on his heels.

Many testified they heard shouted commands in English coming from the direction of the enemy. The soldiers had no idea who was giving legitimate orders.

As for the dead left behind on April 7, a patrol by the 25th’s Company L led by Lieutenant Reginald Hall went out the next day to retrieve the bodies. Along the way one solder drowned crossing a river. Coming within 75 yards of the killing field, another Company L soldier died in an ambush. The patrol halted there and then returned to base empty handed.

The following day, black Lieutenant Abner E. Jackson took 40 soldiers out on a second attempt. Upon reaching the two-day-old corpses, 30 of Jackson’s men refused to touch the dead. Jackson, two medics, and two sergeants bagged the dead in mattress covers. Only then would the 40 carry them back. They also reclaimed all the discarded weapons, ammunition, and equipment they could find.

In the end, throughout the investigation, Curran had his own personal bodyguard. Once the case was settled, he was transferred out, still a captain. Two black lieutenants were judged lacking in leadership qualities and shipped out as well. From the enlisted ranks, Isaiah Adams and Leroy Morgan were charged and found guilty of disobeying orders. Whose orders those may have been—whether from English-speaking Japanese or other Americans—remains unknown. Both Adams and Morgan were returned stateside.

No matter what flawed, limited, biased, or prejudiced evidence came before XIV Corps Commander Oscar Griswold, he agreed with it. He proclaimed the 25th had too little individual and unit jungle training. The junior-grade black officers were poor examples to follow and, lacking initiative, were not motivated to do better.

Overall, Griswold said that the 25th Infantry Regiment, reflective of the 93rd in total, needed improvement. The 93rd’s commander, Maj. Gen. Raymond G. Lehman, disagreed with Griswold’s assessment; Lt. Col. Yon sided with Lehman. The investigation was stacked against the 25th, and the 93rd as well, from start to end.

Two Silver Stars

Corps and division rated the 25th’s performance as only “fair,” but none of the negative statements showed the true heart and soul of the 93rd. For example, in mid-April 1944, a 15-man patrol from the 25th came upon a group of Japanese with well over twice their number and outfitted with machine guns.

Opposing those machine guns was Private Isaac Sermon with his BAR. In the opening exchange of gunfire, Sermon was wounded in the neck. That was the first of four wounds he received while never relenting in the use of his weapon. During the unit’s withdrawal, he kept firing away for 600 yards. By then he was so weak from loss of blood that he collapsed. His comrades carried him back to recover from his wounds.

In another action on May 17, 1944, the 25th’s 2nd Lt. Charles P. Collins led a patrol on Bougainville along with a contingent of men from the 93rd Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop. Overwhelmed by superior enemy firepower and numbers, three troopers were killed outright. Three others were wounded but remained somewhat ambulatory. Collins became the fourth wounded and was temporarily blinded as well.

The remaining men withdrew, believing those left behind had been killed and their bodies not recoverable. In fact, Staff Sergeant Rothchild Webb collected all those wounded. Under his guidance the group hid out for three days in heavily enemy-infested surroundings until they reached their own lines.

For their heroics, Webb and Sermon would receive Silver Star medals.

A Change in Command and a Voice in the Press

By late summer 1944, two events impacted the 93rd Division. Its commander, Maj. Gen. Lehman, became ill and was replaced by 59-year-old Maj. Gen. Harry H. Johnson, a 1916 graduate of Texas A & M and a World War I veteran of the 36th Infantry Division.

For a brief spell Johnson had commanded the 2nd Cavalry Division—the African American division that did not last long upon reaching Algeria. From Italy Johnson was sent to the Pacific with a special set of instructions from his boss, General Douglas MacArthur. MacArthur wanted the 93rd shaped into a real fighting division with no doubts about its capabilities.

The second event was the positive reaction of the American public to articles found in the newspapers—articles such as those written by 51-year-old Walter F. White, executive secretary of the National Association for Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), who took notice of the struggles of the men serving in the 93rd.

White was also a War Department-accredited war correspondent. He could go anywhere the U.S. Army would allow him to report on the war. With growing support of white Americans, the voices of African Americans highlighting the dilemmas facing the 93rd were becoming heard, creating a challenge for the Army to rectify the situation in the Pacific.

With Bougainville secured, in November 1944 the 25th Regiment was assigned to Finschafen, New Guinea, to beef up U.S. defenses there and, in December 1944, the 24th Regiment departed Bougainville and headed to Saipan and Tinian to again perform mopping-up operations and garrison duties.

But what was in store for the 93rd Division? The answer lay in the Halmahera Island Group of eastern Indonesia’s Maluku Islands.

The Japanese Resisters on the Island of Halmahera

Between Indonesia (formerly the Dutch East Indies) and West Papua lies the “K”-shaped island of Halmahera. By the summer of 1944, this 6,860-square-mile island was known to be the home of 30,000 to 40,000 Japanese soldiers along with some advanced airfields.

Douglas MacArthur’s ultimate goal in the Pacific was a grandiose return to the Philippines. A big stepping stone in that direction was Morotai Island, 70 miles north of Halmahera in eastern Indonesia’s Maluku Islands. Morotai was 700 square miles of beautiful tropical paradise with lush jungles, rugged mountains, and white sand beaches. But, on the whole, the Japanese did not think much of Morotai—50 miles long by 26 miles wide.

Although the landscape was beautiful, when the Japanese invaded it in 1942 they found a population of 9,000 living on the fringes of mountainous jungles with a wide variety of vegetation. Malaria was rampant, and the flattest piece of real estate was in the southwest corner called the Doroeba Plains. Thinking it could make a useful landing strip for Japanese planes, it became a fool’s concept. The Plains flooded excessively during the rainy season, and it took too much time, energy, resources, expenditures, and manpower to keep the airfield operational.

The larger, neighboring Halmahera Island proved a far better setting for over half a dozen airfields and was easier to defend, so the Imperial Japanese Army fortified it and left only a token presence of 600 to 800 soldiers on Morotai, whose entire existence was dependent upon the sea lifeline to Halmahera. A constant stream of small boats, most often described as barges, kept going back and forth, providing whatever Major Takenobu Kawashima needed to sustain his 2nd Provisional Raider Unit. If that lifeline were ever cut, those on Morotai would be abandoned.

The thick vegetation and craggy peaks were conducive for bands of Japanese resisters who could hide and live off the land indefinitely if they were cut off from supplies from Halmahera.

MacArthur’s scheme was to completely bypass Halmahera and capture Morotai, which lay 850 miles south and a bit east of the southern tip of Mindanao in the Philippine Islands. Knowing how weak and poorly defended Morotai was, he felt an invasion would be relatively easy and, more importantly, would bring him closer to the Philippines. By mid-July 1944, proposals were being discussed on how to seize the island.

MacArthur foresaw filling the island with 60,000 Allied military personnel, vastly improving what harbors there were, installing fuel-oil storage tanks, then creating an airstrip called Wama Drome at Pitu Airfield. A hospital system that could accommodate 1,900 patients would also be built.

Operation Tradewind

On August 15, 1944, MacArthur gave the order to commence what was code-named Operation Tradewind with XI Corps commander Lt. Gen. Charles P. Hall, the former commander of the 93rd, in charge of it.

More than 40,000 U.S. Army soldiers, supported by U.S. and Australian naval and air forces, prepared to hit the island. Operation Tradewind, supported by carrier planes of the Navy’s 3rd and 7th Fleets as well as fighter-bombers of the Fifth Army Air Force and the RAAF’s 80th Fighter Wing, was scheduled for September 15, 1944.

The U.S. Army’s 31st “Dixie” Infantry Division, which consisted of the 124th, 155th, and 167th Infantry Regiments—all part of the Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi National Guard—would be the main invasion force.

At the time the 31st Infantry Division stormed ashore, Major Kawashima was in charge of the Japanese garrison. He was specifically instructed by his superiors on Halmahera to withdraw into the island’s interior and not challenge the Americans on the landing beaches. He was then to dissolve his force into smaller groups ranging from a dozen to two dozen but nothing larger than 50 in any single locale.

After the Americans came ashore and began hunting for the defenders, life became more and more intolerable for the Japanese; the U. S. Navy’s 40 PT-boat Task Force 701.2, which included Patrol Boat Squadrons 9, 10, 18 and 33, kept intercepting barges. The Americans also used loudspeakers to urge, in Japanese, Nippon’s soldiers to surrender. It met with a bit of success, and several of the enemy, ragged and hungry, gave themselves up.

The haughty Colonel Kisou Ouchi, commander of the 211th Infantry Regiment, took over Morotai’s defenses on October 12, 1944. In addition to his men, there was a mixture of a few other units, including a group of Japanese Army military police known as the Kempei-tai. The Kempei-tai were as bad or worse than Nazi Germany’s SS and Gestapo—more secretive, vicious, and lacking in humanity and morals. (See WWII Quarterly, Spring 2011).

Little is known of Kisou Ouchi, who was, according to tales told by those who surrendered, despised by those under his command. He may have grown up heavily steeped in the samurai warlord traditions of an older Japanese era, and claimed the privileges of the upper class even while his men suffered. He always demanded better living arrangements and more and better food whenever it became available.

Clash Between the Blue Helmet and the Dixie

From the outset it seems that the 93rd Infantry Division may never had been considered for any part of the action. Finally, on April 4, 1945—nearly eight months after Operation Tradewind was launched—the decision was made to bring the 93rd ashore at Morotai. The men of the Blue Helmet Division had almost given up hope that they would ever see action and have the opportunity to prove that they were just as good as any all-white division.

They almost didn’t get the chance. Nelson Peery, a black platoon leader in Company C of the 93rd, recalled that the tension between his unit and the 31st “Dixie” Division nearly erupted into a race war. While the 93rd was sailing to Morotai, a black sailor on the transport ship mentioned that the 31st, which the 93rd was coming in to relieve, was “the Goddamndest set of Ku Kluxers ever seen…. The 31st said they gonna lynch any nigger look cross-eyed at the women [Army nurses].”

The landing craft approached the beach. Peery said that he could see a group of people on the shore—a group of white MPs from the Dixie Division, some holding rifles, a group of nurses from the hospital that had been established nearby, and “the most forlorn group of Negro soldiers [from a water-filtration unit] I had ever seen.”

Once on the beach, Peery was approached by one of the “forlorn” black soldiers who seemed overjoyed to see him.

“Jesus Christ! I’m glad to see a black man with a rifle.”

“What’s the matter, man?” a surprised Peery replied.

“We been catchin’ hell here. These white *** got all the guns—they’re the military police and they been beating us up.”

Peery realized that the rumor he had heard on the boat was true. “So they want to lynch somebody,” he said. “I turned to the men filing out of the landing craft. ‘Looks like the Dixie boys been giving these men a hard time.’”

Peery’s platoon was having none of it. The men loaded their rifles and clicked off the safeties, ready for whatever might come. The superheated atmosphere was about to burst into flames. The nurses looked worried, and the white MPs appeared agitated and ready for a brawl.

Fighting With MPs

A nervous Peery said, “This was worse than combat. We greatly outnumbered them, but we were bunched together for a slaughter. The officers on deck talked together nervously. Behind them, the sailors glanced around for cover. The white soldiers shifted their weapons. We were more than they had bargained for. I turned my back on them and called to the section, ‘OK, men, fall in here.’”

His men did as ordered, but a drunken white MP started toward the group, getting ready to unholster his .45. But he stopped when he saw the black solders’ weapons brought up to firing position and aimed at him.

“The nurses screamed and ran for the hospital tents,” said Peery. “The white soldiers scattered for cover. Men from Company C ran from the landing craft…. Captain Williams, the Negro commander of Company C, ran between the groups. Pulling his .45 from its holster, he shouted for attention. Our men lowered their rifles and snapped to. The terrified white soldier did not move.”

Captain Williams ordered the drunken white soldier to get back to his company; the soldier obeyed. The 368th’s 1st Battalion commander arrived on the scene, and he and Williams held a brief conference. Soon the situation was defused, and the white soldiers, grumbling, departed the scene.

“We marched to the edge of the swamp that the commander of the 31st had designated our bivouac area, said Peery, but all was not sweetness and light. “Tension rose immediately between the white MPs and our soldiers,” he noted. “Arrests and fights between them occurred almost daily. Just as the tension reached the flash point, our division headquarters moved to the island.

“General Johnson, our new commanding officer and the senior officer on the island, took command. Our military police replaced those of the Dixie Division and the bottom rail went to the top. A few cracked heads and the Dixie boys accepted the black MPs. Before any serious trouble developed, the 31st left for the invasion of the Philippines.”

The 93rd’s First Prisoner of War

The 93rd’s arrival did not mean an immediate combat role; the men found the usual tasks awaiting them: guard duty, unloading ships, and stacking piles of supplies. Only this time, their Australian counterparts worked alongside them, virtually shoulder to shoulder.

At last it came time for combat. From the island’s southwest corner the 93rd’s three regiments would conduct patrols lasting from two to three weeks at a time seeking straggling Japanese holdouts. Their areas of concentration were Wajaboeia, Libano, and Sopi.

One area of particular interest was where the River Tijoe emptied into the Pacific. It was the chosen landing site for supply barges coming from Halmahera Island.

During an April 15, 1945, patrol, men of the 369th Regiment eliminated four Japanese in a shootout. Six days later the 369th brought in the 93rd’s first prisoner of war. All the while the Imperial Japanese Navy kept up an intermittent run of barges full of supplies and reinforcements to Morotai. It seemed Ouchi’s numbers may have been on the increase.

On May 13, U.S. Navy PT boats chased four Japanese barges that had left Halmahera and were heading for Morotai. Two were destroyed en route, a third was hit just short of Morotai, and the fourth landed, was unloaded, and was hidden in the cove of the Tijoe River outlet. A 25th Regiment patrol eventually found and destroyed it.

On that same day a patrol from the 25th’s 3rd Battalion was just north of Libano when it came upon eight well-equipped Japanese who may have been connected to the recently found barge. It was a successful hunt for those of the 3rd Battalion, but in June the 25th would be moved to the Green Islands, where once again they would be used primarily in a service and security role.

Crawford’s Patrols

On May 24, Company F of the 368th Regiment sent out a patrol led by Lieutenant Richard L. Crawford. Their starting point was the well-known streambed of the Tijoe River. Moving inland, Crawford’s 12-man patrol quickly found and began tracking a set of footprints that followed the stream. Two miles later the footprints turned away from the water and went up a rocky ridge onto a jungle-covered hill.

Carrying on stealthily, Crawford’s patrol spotted seven unsuspecting Japanese soldiers resting; all wore newly issued, immaculate uniforms. Only one carried a rifle while the others had just pistols. From their hiding place, Crawford and his men watched as one soldier spent a considerable amount of time looking into a hand-held mirror while grooming his beard. The Japanese seemed more like they were preparing for a parade than worried about the possibility of being ambushed.

Crawford’s patrol opened fire, killing six; the seventh got away, but a blood trail leading into the jungle showed that he had been wounded. Through documents on the bodies, it was determined that these soldiers were, indeed, Kempei-tai.

On July 11, another Crawford-led patrol was again in the Tijoe River area. This 12-man patrol was to spend two weeks in the vicinity scouting for Japanese—especially Colonel Ouchi. On their last day they found a wounded Japanese soldier and took him prisoner. For the aid, comfort, and rations given him, he was happy to give up the location of a nearby camp where Ouchi had his headquarters.

The patrol found a three-hut camp in a clearing occupied by 10 or 12 Japanese. A brief firefight netted one enemy dead, at least six wounded, and the rest running for their lives. They left behind ample piles of rice, blankets, ammunition, and grenades.

Another two days of patrolling netted nothing. On August 2, Crawford’s men heard wood being chopped. Homing in on the sound, they found a four-hut camp with a number of Japanese napping. Another half dozen had just deposited boxes of supplies they had carried in and were heading downhill to swim in the river.

Positioning his patrol to cover both camp and swimmers, Crawford tried talking the bathers into surrendering. They refused and ran off into the jungle. At the camp the rest of Crawford’s men opened up on the Japanese, killing seven on the spot. Two others ran off into the jungle, and one man was captured.

The Capture of Colonel Ouchi

As luck would have it, Colonel Ouchi was the man captured. While Ouchi was being led away by Sergeant Jack McKenzie, a Japanese soldier playing dead rose up to take out the sergeant. Firing his carbine from the hip without letting go of his prisoner, McKenzie shot his attacker in the head. Colonel Ouchi became the highest ranking Japanese officer captured under combat conditions prior to Japan’s surrender.

For their contributions to Ouchi’s capture, Sergeant Alfonzia Dillon received the Silver Star while Sergeant Albert Morrison and Privates First Class Robert A. Evans and Elmer Sloan received Bronze Stars.

With their commander in captivity, more than 600 other Japanese finally came out of hiding to surrender.

The 93rd Division saw very little additional combat, but the men did make a contribution to victory in the Pacific. From April 10 to July 10, 1945, the division discharged and offloaded 311,552 tons of supplies and equipment, moved thousands of Allied troops from transports to staging areas and back to embarkation points, and improved harbor facilities, roads, and camp sites. But there were still battles to be fought.

While on Jolo Island in the Philippines’ Sulu Archipelago, between Borneo and Mindanao, on July 17, 1945, a patrol from Company I, 368th Regiment was ambushed by a Japanese force three times its size. With bullets flying everywhere, Staff Sergeant Leonard E. Dowden from New Orleans, Louisiana, moved his squad to within 30 yards of the Japanese but was then cut down by enemy fire.

Despite being gravely wounded, Dowden crawled forward alone to assault a machine-gun position with grenades. Just as he was about to throw a grenade, a burst of fire killed him. The patrol was able to fight off the enemy attack with only 18 casualties. For the extraordinary heroism that cost him his life, Staff Sergeant Dowden posthumously received the Distinguished Service Cross—the nation’s second-highest award for valor. He was the only member of the 93rd Infantry Division to earn the DSC during the war.

War’s End: Returning to Jim Crow

By war’s end the 93rd would get as far as Mindanao and Leyte in the Philippines while under the command of Brig. Gen. Leonard R. Boyd. When official word of Japan’s surrender came, since there was a shortage of fireworks, the rifles blazed away in celebration. Sergeant James Yancy, 369th Infantry Regiment, said the 93rd joined in the celebration. Then a white officer came over to Yancy’s elated group and ordered them to cease firing; all of their weapons were confiscated. The white troops kept firing away with their celebrations.

During their two years in the Southwest Pacific, the men of the 93rd accumulated 825 military awards for valor and meritorious service: one Distinguished Service Cross, one Distinguished Service Medal, five Silver Stars, five Legions of Merit, 686 Bronze Stars, and 27 Air Medals. The 93rd Infantry Division sailed home and was deactivated at their former port of departure—Camp Stoneman, California, on February 3, 1946. The American military was desegregated two years later by order of President Harry. S. Truman.

Once back on U.S. soil, many African American soldiers had mixed feelings about their wartime service. For some their brief time in combat proved that they were just as capable as white soldiers. For others returning to civilian status meant a return to racism, Jim Crow laws, institutionalized discrimination, and restrictions on their personal freedoms. As one 93rd Infantry Division veteran said, “I got through fighting in the P.T.O. [Pacific Theater of Operations] and now I’ve got to fight in the S.T.O., U.S.A. [Southern Theater of Operations in the United States].”

I am amazed to find the history in the printed word of the events that my dad told me of during WW2and his time in the 93rd,l’m proud of all the of Accomplishments and all of the barriers and setbacks they had to overcome, God bless them all

My daughter considered the U.S. Army after high school and brought a pic of her grandpa Sgt. Tommie Ryan. He enlisted at 17 and reported a month later for WWII when he was 18. When the recruiter saw his photo, he asked “Was he a pilot?” I explained he was a sharpshooter, Golden Glove Boxer and diesel airline mechanic. I added. “Although he did write his mother to say he learned to fly. She was terrified.” The recruiter said, “Well, I asked because he’s wearing a pilot’s hat.” He also saw the emblem on his sleeve for the Pacific Theatre. Although my daughter didn’t join, we both left the office with a renewed respect for my dad. We knew he was important to us, but we didn’t know how important he was to this country. I added his photo to his profile on http://www.Fold3.com.

Just wanted to share this article about my father George Ruth who served and 93rd Infantry Division during WWII. He recently celebrated his 93rd Birthday.

Thank you for your time.

https://theeagle.com/news/local/gallery-93-year-old-world-war-ii-vet-participates-in-history-in-motion-at-the/collection_22a52e7a-4525-11ec-953d-cf7aa46efa52.html#7

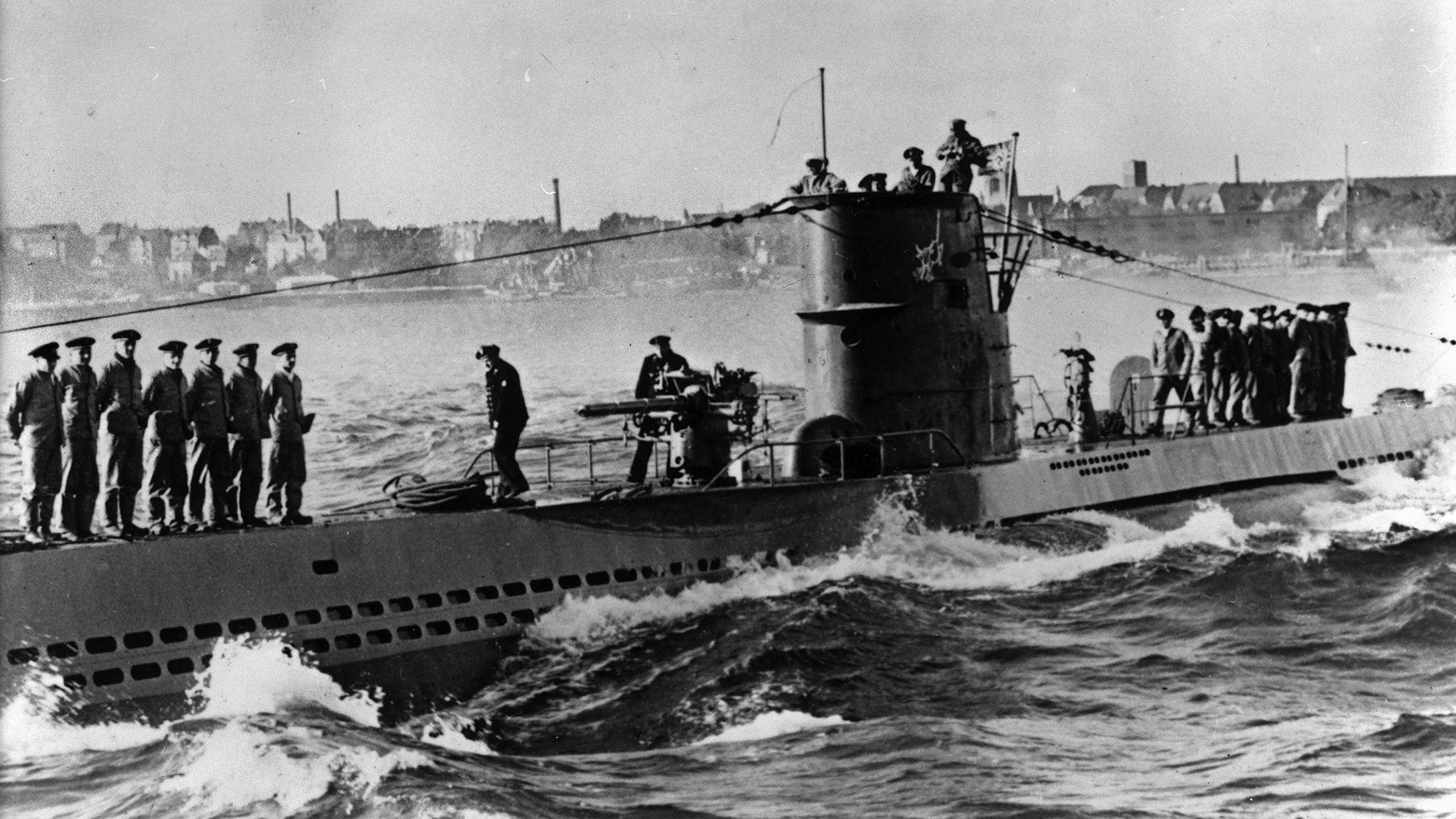

There’s an well-researched book – “Black Submariners in the US Navy” by Glenn Knobloch, an excellent resource detailing the hundreds of Black submariners who served – and died – on US submarines.

My father. LCDR Killraine Newton, was in the Pacific on the submarine USS Sailfish (SS-192) for the 11th and 12th war patrols. He started out as a Steward’s Mate and retired as a Lieutenant Commander. His motto – “The Hell I Can’t.” He’s mentioned in this book, and another recent book, “Strike of the Sailfish” by Stephen Moore. God rest all those men on Eternal Patrol.