By William F. Floyd, Jr.

The two exits from the American landing zones at Utah Beach were entrusted to the 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division. The regiment’s job was to clear the exits of German resistance. Lt. Col. Robert Cole, commander of the 3rd Battalion of the regiment, was first to arrive following the airdrop on June 6, 1944. Cole collected 75 men from his battalion, together with other troops from the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment and the 82nd Airborne Division. The combined group headed toward the village of St.-Martin-de-Varreville. About one kilometer from their destination was an ominous-looking cluster of German coastal artillery barracks.

Cole tasked Lt. Col. Patrick Cassidy of the 1st Battalion of the 502nd with clearing and securing the enemy installation. Cassidy dispatched Sergeant Harrison Summers from the 1st Battalion with 15 men to clear the objective. Although the number of troops detailed for the mission was not nearly enough to take on a full German company that might contain upward of 100 men, it was all that could be spared. Summers and his small force set out immediately with some in the group being reluctant to follow an unknown sergeant.

“Go up to the top of the rise and watch for anything approaching and don’t let anything come over that hill and get on my flank,” Summers told Sergeant Leland Baker. “Stay there until you are told to come back.”

Summers charged the first building, but to his amazement, no one followed him. He kicked in the door and began firing with his submachine gun, killing four Germans, with the rest retreating to the next house. Summers, still without help, charged the next building. The Germans inside fled. Inspired by Summers’ heroics, Private William Burt came out of the ditch where the attackers had been concealed and laid down a suppressing fire on the third building.

Summers again moved forward, but this time the Germans were ready. Suddenly, the building erupted with fire. The Germans had cut holes in the building and were firing through them. With the help of Burt’s submachine gun fire and by running in a zigzag fashion, Summers did not get hit. He kicked in the door, killed six Germans, and drove the rest from the building. Physically and mentally exhausted, Summers dropped to the ground.

After resting for about a half hour, his hesitant squad caught up with him and replenished his ammunition. As he got to his feet, an unknown captain from the 101st Airborne Division, who had joined the force because he had missed his drop zone by many miles, appeared at his side. “I’ll go with you,” the captain said. No sooner had he uttered the words than he was shot through the heart. Summers charged another building and gunned down six more Germans. The rest surrendered, and Summers turned them over to his squad.

One of the men from his squad, Private John Camien, joined Summers to secure the last few buildings. The two moved from building to building, taking turns charging and giving covering fire. Burt was still with them, putting his machine gun to good use. With just two buildings left to clear, Summers kicked in the door of the first one and shot 15 German artillerymen as they sat eating breakfast. The final building loomed in front of the Americans. It was the largest of the bunch and was flanked by a storage shed and a haystack. Burt used tracer bullets to set the shed and haystack on fire. The shed, which was full of ammunition, exploded, sending smoke and flames skyward. The explosion drove 30 Germans into the open where Summers, Camien, and Burt gunned them down while others fled.

When it was all over, Summers collapsed. The fighting had lasted nearly five hours. One of the men asked him how he felt. “Not very good,” said Summers. “It was all kind of crazy. I’m sure I’ll never do anything like that again.”

Summers would later receive a battlefield commission, as well as the Distinguished Service Cross, for his valor that day. He was nominated for the Medal of Honor, but the paperwork got lost. Following his death in 1983, another effort was made to have the medal awarded posthumously, but without success. Nevertheless, future generations of paratroopers would consider him a legend for his feats on D-Day.

“You will enter the continent of Europe and undertake operations aimed at the heart of Germany and the destruction of her armed forces.” This was the assignment given to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, on February 12, 1944. Operation Overlord would become the largest amphibious invasion in history. The massive undertaking ultimately would involve 156,000 troops, 5,000 ships and landing craft, 50,000 vehicles, and 11,000 aircraft.

Approximately 13,000 U.S. paratroopers belonging to Maj. Gen. Maxwell Taylor’s 101st Airborne Division and Brig. Gen. James Gavin’s 82nd Airborne Division began parachuting into the black sky over France at 1 am on Tuesday, June 6. The 101st Airborne was scheduled to be dropped near Vierville to support the Utah Beach landings, and the 82nd Airborne was scheduled to be dropped near Sainte-Mere-Eglise to protect the First Army’s right flank and secure a bridgehead on the west bank of the Merderet River. In addition, 2,500 glider-born troops would land under cover of darkness to lend additional support.

Pathfinders had been dropped an hour earlier to illuminate the drop zones with electronic transmitters and signal lamps, but some had missed their landing zones or found German troops manning positions they were supposed to mark. Once on the ground, the paratroopers of the 101st Airborne Division had as their primary objective the securing of four elevated causeways leading west from Utah Beach to the interior of the Cotentin Peninsula.

The Allies had chosen the strip of coast in Normandy for their amphibious landing in part because the Germans were convinced that the attack would come in the Pas de Calais region. Nevertheless, in the weeks leading up to the invasion German leader Adolf Hitler, Field Marshall Erwin Rommel, and Admiral Theodor Krancke all had become nervous about a possible Allied invasion of Normandy and favored the strengthening of forces in the Cotentin Peninsula. The German commanders seemed to have a sixth sense that the Allies might attempt to capture the port of Cherbourg through which to funnel the men and materials needed to open a western front against the Third Reich. In November 1943, Hitler had given Rommel command of Army Group B, responsible for the defenses of northern France. As for Krancke, he was commander in chief of Navy Group Command West headquartered in Paris.

The addition of new German units forced the Allies to revise their airdrop plans. For example, the Allies initially planned to drop the 82nd Airborne at the base of the peninsula. But the appearance on aerial reconnaissance photos of new German units forced them to ultimately drop the 82nd Airborne farther north.

Anchoring the eastern side of the Cotentin Peninsula was Lt. Gen. Karl-Wilhelm von Schlieben’s 709th Infantry Division. The Germans moved Maj. Gen. Wilhelm Falley’s 91st Infantry Division to the base of the peninsula to assist the 709th and further strengthened the 91st by adding Maj. Gen. Friedrich August Freiherr von der Heydte’s 6th Parachute Regiment. In addition, the Germans moved the 206th Panzer Battalion forward to support these units. The job confronting the Allies in clearing the Cotentin would be further complicated by the arrival from Brittany of General of Artillery Wilhelm Fahrmbacher’s 77th Infantry Division, which Rommel would order on D-Day to shift east as quickly as possible to assist units already engaged against the Allied right flank.

On June 8, two days after the initial landings, Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in Europe General Dwight D. Eisenhower, along with British Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay and British General Sir Bernard Montgomery, visited all five of the landing beaches. During that time, Eisenhower held a lengthy meeting with U.S. First Army commander Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley.

Eisenhower was concerned not only by the slow progress of Montgomery’s forces toward Caen, but also with the heavy losses the Germans had inflicted upon the Americans at Omaha Beach on D-Day. Moreover, Eisenhower was displeased that the Americans on Utah and Omaha Beaches were still separated from each other by nearly a 10-mile gap after 48 hours of fighting. Eisenhower ordered Bradley to unite the forces in a single beachhead.

To facilitate the effort, Eisenhower revised the Americans’ immediate objectives. First, he wanted to eliminate the pocket of German resistance near Sainte-Mere-Eglise, which would unite Maj. Gen. Raymond Barton’s 4th Infantry Division with elements of the 82nd Airborne Division. Second, Eisenhower wanted Bradley’s First Army to seize control of Carentan.

Carentan is located in the Douve River Valley at the base of the Cotentin Peninsula. By 1944, Carentan had a population of 4,000. The important road hub was located between the two American landing beaches, Utah and Omaha.

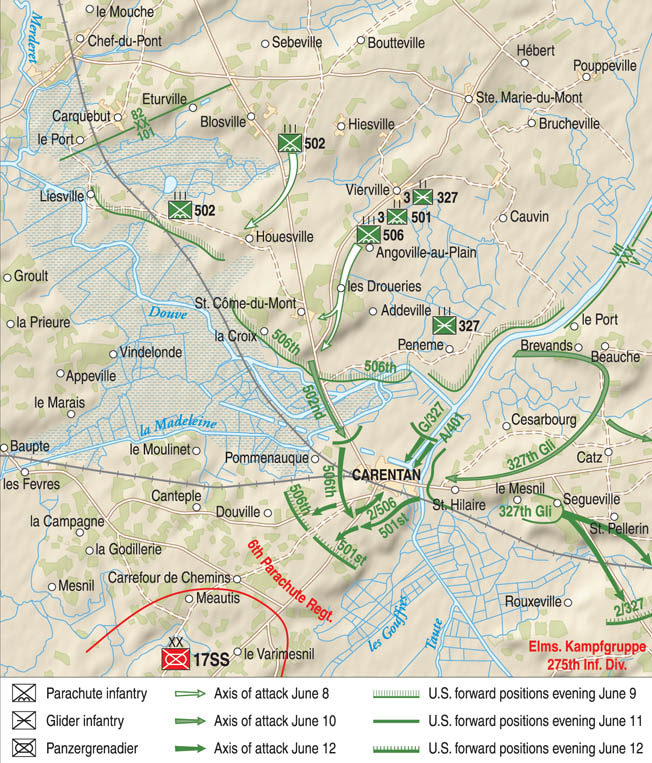

Bradley tasked the 101st Airborne, which comprised the 501st, 502nd, and 506th Parachute Infantry Regiments, with capturing Carentan. This involved a change in the primary effort of the U.S. VII Corps, which was led by Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins. Bradley instructed Collins that if necessary he should reinforce the 101st Airborne so that it could punch its way through to Carentan to link up with Maj. Gen. Leonard T. Gerow’s V Corps in the Omaha sector.

Any capture of Carentan meant that Sainte-Come-du-Mont, which lay three miles north of Carentan, would have to be taken first. A scratch force of the 101st Airborne tried to take the town on June 6 but failed. They had run headlong into von der Heydte’s elite German paratroopers.

Two days later, Taylor organized a more formal attack against Sainte-Come-du-Mont. At 4:45 am on June 8, two battalions of the 506th attacked from the north, while the 3rd Battalion of the 501st Parachute Infantry and the 1st Battalion of the 401st Glider Infantry struck from the east. The paratroopers’ advance was preceded by a barrage from the 65th Armored Field Artillery and the 101st Airborne’s 377th Parachute Field Artillery. Given the condition of the American troops, who had been fighting without proper food or sleep for three days, the attack was disjointed.

The five battalions became intermingled during a series of clumsy and uncoordinated attacks that day. For most of the attackers, the day was one of random firefights with groups of Germans defending buildings, intersections, or hedgerows. Despite the confused nature of the American attack, the Germans began withdrawing toward Carentan.

Lieutenant Colonel Julian Ewell and his 3rd Battalion, 501st Parachute Infantry, kept a close watch on the Germans as they retreated toward Carentan. Ewell and his men tried to cut them off before they could reach the bridges leading into Carentan. As they made this move, they came under machine-gun fire from near the bridge and artillery fire from Carentan. Ewell and his men shifted to the east side of the N-13 Highway, which connected Cherbourg to Carentan, and began taking fire from the north. All day long they fought off six different counterattacks. By late afternoon the fighting had stopped. Most of the Germans had escaped to Carentan. Although the Americans had secured Sainte-Come-du-Mont, they had failed to destroy the enemy. In spite of the incomplete victory, the capture of Sainte-Come-du-Mont was a preliminary step in the eventual capture of Carentan.

Rommel had given von der Heydte specific orders to defend Carentan to the last man. But the 101st Airborne had equally important orders. Resting on their shoulders was the responsibility for capturing Carentan so that soldiers of the VII Corps and V Corps could link up and the Americans could turn their attention to capturing the deep-water port of Cherbourg. This would secure the Cotentin Peninsula and enable the Allies to focus on breaking into the interior of France. Bradley regarded the capture of Cherbourg as the Americans’ primary objective at that point.

For the most part, the Americans were up against battle-tested Germans. “The Germans are staying in there just by the guts of their soldiers,” said Barton. “We outnumber them 10 to 1 in infantry, 50 to 1 in artillery, and infinite numbers in the air.”

Barton wanted his unit commanders to convince their soldiers that they had to fight just as hard for their country as the Germans would be fighting for theirs. “In comparing the average American, British, or Canadian soldier with the average German soldier, it is difficult to deny that the German was by far, in most cases, a superior fighting man,” wrote U.S. war correspondent Robert Miller. “He was better trained, better disciplined, and in most cases carried out his assignment with much greater efficiency than we did…. The average American fighting in Europe today is discontented, he does not want to be here, he is not a soldier, he is a civilian in uniform.”

Although the Germans respected the elite nature of the U.S. paratroopers and rangers, they had little regard for the fighting qualities of the average infantryman. Most German soldiers were heavily indoctrinated by Nazi propaganda. The leadership in Berlin repeatedly told the soldiers that defeat would mean the annihilation of their Fatherland and that the Allies planned to wipe out the German race. Even the soldiers who wanted to surrender were afraid to do so. Propaganda persuaded them that they would not be safe in an England, which would be bombarded by Germany’s new secret weapons. As in all armies, the combat performance of American troops would vary from unit to unit. Not long after the landings at Normandy, a great number of the Americans began to lose their fear of the Germans, a feeling that grew as the fighting continued.

Taylor planned to capture Carentan with a pincer movement that entailed sending his troops across the Douve River in two places. But first he needed a good handle on the strength of the German positions. For that reason, the American paratroopers spent June 9 scouting the terrain and reconnoitering the strongpoints held by von der Heydte’s men. One of the reconnaissance teams that forded the Douve River was driven back by concentrated German machine gun fire. Taylor received aerial reconnaissance information indicating that Carentan was occupied by only one German battalion, but events would prove the intelligence information wrong.

Taylor’s plan called for the 327th Glider Infantry Regiment to cross at Brevands and push south. Part of the same regiment would move southeast and link up with the 29th Division’s 175th Infantry Regiment near Insigny. The rest of the regiment would circle around Carentan from the southeast. The 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment, with Lt. Col. Cole’s 3rd Battalion in the lead, was to cross over a succession of four bridges, swing to the southwest, and seize Hill 30, a commanding piece of terrain that allowed those controlling it to interdict movement in and out of Carentan. After that objective was achieved, Cole’s men were to link up with the 327th Glider Infantry. Following Cole would be the rest of the 502nd Parachute Infantry and the 506th Parachute Infantry. After the encirclement was completed, the main attack would begin. When the Germans tried to withdraw, they would have nowhere to go.

The 502nd Parachute Infantry had been activated at Fort Benning, Georgia, in February 1942. After the men had completed their training, they were assigned to the 101st Airborne Division on August 15 as its first parachute regiment. It subsequently relocated to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, on September 24. After another year of training, it was sent to Camp Shanks, New York, on August 24, 1943. The “Five-Oh-Deuce” was commanded by Colonel John G. Van Horn Moseley Jr. The unit arrived in England on October 18, 1943, where it undertook intense training for an additional seven months, which included routine 25-mile hikes, daily close combat exercises, and rigorous training in the use of German weapons.

Before entering Carentan, Lt. Col. Cole’s movement was hindered because the causeway he had to cross spanned a long stretch of marsh. For almost 1,000 yards the route was devoid of cover. The causeway included four bridges, one of which had already been destroyed. The timetable for Cole’s unit was to reach the second bridge, the one that had been destroyed, by 3 am on June 10. It was hoped that by this time the engineers would have the blown-up section repaired so the American paratroopers could cross.

The marshes over which the causeway passed were artificial. Rommel had ordered his engineers to flood the Douve Valley to prevent Allied parachute landings. An earlier aerial reconnaissance indicated that the causeway was the only alternative for an advance toward Carentan because the Germans already had demolished the railway bridge over the Douve River. At 1:30 am on June 10, a reconnaissance party found that the 12-foot gap in the second bridge had not been repaired. The engineers had stopped work when a German artillery barrage landed near their position.

When Lt. Col. Cole and his men approached the second bridge, Cole found it was not repaired. At 4 am, the attack was cancelled. But several miles down the Douve Valley another crossing was almost complete. The 327th Glider Regiment was crossing the river in rubber boats. The company had crossed the river at 1:45 am, and by 6 am the entire regiment was across. A new attack led by Cole was now planned for the afternoon of June 10. Cole ordered a small party of three to repair the destroyed bridge using planking left by U.S. engineers whom the Germans had driven off a short time before. At 2 pm, a wobbly bridge was completed.

Cole’s battalion now began crossing the bridge led by the intelligence section. Slowly and cautiously each man crossed the bridge until the planks eventually gave way, meaning that many of the soldiers crossed the Douve River by hanging on to the ropes. During the crossing the Americans were under intermittent fire mostly from German 88mm artillery or mortars. As they continued forward and approached the fourth bridge, the fire became much heavier. The Germans were now throwing everything they had at the Americans, including accurate sniper fire. Cover for the troopers was practically nonexistent, and most just tried to hug the ground. On either side of the causeway, men were being hit at an alarming rate. The terrible scene went on for hours. Cole attempted to rally his men but was unsuccessful; the crossing was completely stalled.

Only nightfall and American artillery fire offered any relief. This moment was short lived as two German Ju-87 Stukas attacked. The aircraft strafed and bombed the causeway, killing 30 men, which knocked I Company completely out of the battle. At that point, the casualties suffered by the 3rd Battalion of the 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment were estimated at 67 percent. This section of the Carentan Highway became known as Purple Heart Lane.

About that same time, the German paratroopers, who had been very low on ammunition, were being resupplied. Von der Heydte had previously radioed his superiors and informed them that his men could not continue fighting unless they received immediate resupply. The situation had become so desperate that all of the rifle ammunition used by the rifle companies had been collected and given to the machine gun crews. In response to von der Heydte’s request, Ju-52 transports had dropped pallets with ammunition in the rear area that night, and this was brought forward to the troops on the front line. Without the additional ammunition, the Germans may have had to give up the defense of Carentan.

Cole had gone back to regimental headquarters and had received orders to continue the attack. For the remainder of the night he prepared what was left of his battalion for another move toward Carentan. Company H with its 84 men would lead the attack, and Company G would follow with its 60 remaining troopers. Headquarters reinforced the attack with another 121 men.

At 4 am on June 11, they moved out. In the darkness they made it to the fourth bridge over the Madeleine River without taking any casualties. The lead scouts veered to the right, which led to hedgerows and four stone buildings, key objectives. The Germans were in the buildings and behind the hedges. The lead scout, Private Albert Dieter, headed straight for the farmhouse. The men behind him were strung out some 200 yards, almost all the way back to the bridge. When Dieter got to within a few yards of the hedgerow, the Germans opened fire. Dieter received a bad arm wound, but he would survive the battle. Two other troopers, close by, were killed instantly. Cole was not far away and requested artillery fire on the German positions. After some harsh words, Cole got what he wanted. Cole watched the artillery coming but did not observe any slackening in the German fire. Cole slid back into the ditch to try and figure out what to do next. Should he sidestep the Germans or should he attack? For a few minutes he was in a quandary. Three days earlier, he had ordered a successful bayonet charge against the Germans. He pondered the pros and cons and finally decided to launch another bayonet attack.

Cole looked across the road and saw his executive officer, Major John Stopka, lying in a ditch. “We’re going to order smoke from the artillery and make a bayonet charge on the house,” Cole told him. Stopka only told those immediately around him about the charge. In a few minutes, the smoke shells began exploding in front of the buildings. Cole blew the whistle for the attack to begin, but only about 20 men got up to follow him. Stopka realized what had happened and began to round up more men to participate in the attack.

By this time, Cole was way ahead of everyone else. When he looked back, he saw almost no one following. As he kneeled down to look back at the ditches, he finally saw several of his men moving toward him. Despite the early disorder, the men charged across the field under heavy enemy fire east of a farmhouse. The men became closely bunched and were told several times by Cole to fan out. Men from Company H reached the farmhouse first and found it abandoned.

To the west on higher ground, the Germans occupied rifle pits and machine-gun emplacements along a hedgerow. The location was soon overrun by the Americans using grenades and bayonets. The enemy’s main line of defense was now broken, but they still held ground to the south from which the Americans continued to receive fire. Cole wanted to take advantage of the enemy’s disorganization and keep moving, but 3rd Battalion was in no condition to keep going. Word was sent to the rear to request that the 1st Battalion, 502nd Parachute Infantry advance, pass through the 3rd Battalion, and continue the attack south to the high ground.

Instead of relieving the 3rd Battalion, the 1st reinforced it to help secure the ground already gained. At around 6:30 pm, Cole informed regiment that he planned to withdraw and asked to have covering fire and smoke when the time came. Cole’s artillery liaison officer, Captain Julian Rosemund, after much difficulty, was finally able to reach the artillery command post by radio.

Every gun was trained on the German position. The artillery barrage lasted only five minutes, and when it stopped the sound of German gunfire was heard receding southward. At 8 pm the 2nd Battalion came up to relieve the 1st and 3rd Battalions. It was a successful end to a long, bloody, tragic day for Cole’s paratroopers. The battalion had gone into action with 700 men, but was down to 132. The exhausted 502nd Parachute Infantry had done its job; it had opened the northern route into Carentan. In executing their mission, they had beaten their German counterparts. Cole would be awarded the Medal of Honor for his exploits on June 11 but did not live to receive it. Sadly, a German sniper shot him in September while he was fighting with the 101st Airborne Division in Holland.

During the two days of fighting to get across the causeway, the left wing of the 101st had also been pressing southward. The 327th Glider Infantry made good progress on June 10 and 11. Glider troops seized Brevands and made contact with reconnaissance troops from the 29th Division at Arville-sur-le-Vey on the west bank of the Vire River. The regiment’s 1st Battalion met up with part of the 175th Infantry. The rest of the 327th turned west and advanced into the northern outskirts of Carentan by June 12.

During the same period, the 101st’s Airborne reserve unit, the 501st Parachute Infantry crossed the Douve, moved around the eastern end of Carentan, and made it to Hill 30, the key objective south of the town. On the evening of June 11-12, Allied naval guns, artillery, mortars, and tank destroyers turned much of Carentan into rubble. In the meantime, the 506th Parachute Infantry crossed the same bridge used earlier by Cole’s troopers. They moved southwest in a disorganized, disorienting night march around Carentan that had started at 2 am on June 12. The 506th Parachute Infantry worked its way to Hill 30 and into position for the attack on Carentan by daylight.

At 6 am, the Germans in Carentan were hit from the north by the 1st Battalion of the 401st Glider Infantry and the south by the 2nd Battalion of the 506th Parachute Infantry. Unbeknownst to the Americans, the Germans in the town were low on ammunition and had pulled back to the southwestern part of the town. There were some stragglers left behind to try to slow down the Americans. At 7 am on June 12, enemy resistance had come to an end. Carentan now belonged to the Americans.

But this was not the end of the story. The Germans wanted Carentan back. The effort to unite the Utah and Omaha sectors was about to be decided near Carentan. Field Marshal Rommel was less concerned about the Americans closing the gap in the two beachheads than by the threat to Carentan.

On the afternoon of June 12, the 506th and the 501st Parachute Infantry Regiments had started to secure the southeastern approaches to the town. Suddenly, a small German force attacked the 506th Parachute Infantry. The Germans were driven back to Douville, where the American advance was stopped by entrenched Germans. The ensuing firefight lasted the rest of the day. On the morning of June 13, Taylor placed the 506th and the 501st in the hedgerows and on the high ground southwest of Carentan. As the American forces advanced, the Germans launched a major counterattack. The Germans had assembled a battle group that consisted of tanks and infantry from Brig. Gen. Otto Baum’s newly arrived 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division and the remnants of von der Heydte’s 6th Parachute Regiment. The Germans struck the 501st Parachute Infantry south of Hill 30. Another powerful attack occurred when the 506th was attacked along the Carentan-Baupte road west of Hill 30. While defending themselves against the attack, the American units became intermingled and accidentally fired on each other. The situation was growing more desperate by the minute for the Americans, with some units falling back.

At the request of Colonel Robert Strayer, commander of the 2nd Battalion, 506th Parachute Infantry, Taylor sent reinforcements to assist the beleaguered Americans and also called in air support. Assistance came in the form of strafing P-47 fighter bombers, antitank guns, and elements of the 2nd Battalion, 502nd Parachute Infantry. Soon the rumbling of tanks could be heard behind the American lines. The tanks were part of a major relief effort by the 2nd Armored Division, which had arrived in Normandy a few days earlier. The American tanks repulsed the German forces along the two main roads and in the surrounding fields.

Tanks from the 2nd Armored’s Combat Command A had turned the tide of battle. The Germans were sent into headlong retreat, and the threat to Carentan was over. The arrival of the 2nd Armored’s tanks and infantrymen at this key moment on June 13 was no accident. It resulted from the use of intelligence information received from Bradley, who was one of the select few Allied officers to be privy to information received from Ultra, the Allied intelligence program that cracked encrypted German communications. On June 12, Bradley received an Ultra flash message that revealed the German counterattack plans for June 13 at Carentan. “This was one of the rare times in the war when I unreservedly believed Ultra and reacted to it tactically,” Bradley later said.

The importance of the capture of Carentan cannot be overstated as part of the success of the Normandy landings. It closed the gap between the Utah and Omaha beachheads, the last gap between the D-Day landing zones, and removed any danger of the Germans isolating the Utah beachheads.

On June 15, the 101st Airborne Division was assigned to VIII Corps and remained in a defensive position around Carentan until relieved on June 27 by the U.S. 83rd Infantry Division. On June 30, the 101st Airborne replaced the 4th Division at Cherbourg, where it remained until returning to England for replacements and training. After Carentan, the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment’s Company E fought in Holland, held the perimeter at Bastogne, led the counterattack in the Battle of the Bulge, and participated in the Rhineland campaign.

The 101st Airborne Division suffered 150 percent casualties. The Medal of Honor Citation for Cole reads, in part, “Lieutenant Colonel Cole was personally leading his battalion in forcing the last four bridges on the road to Carentan when his entire unit was suddenly pinned to the ground by intense and withering enemy rifle, machine-gun, mortar, and artillery fire placed upon them from well-prepared and heavily fortified positions within 150 yards of the foremost elements. After the devastating and unceasing enemy fire had for over one hour prevented any move and inflicted numerous casualties, Cole, observing this almost hopeless situation, courageously issued orders to assault the enemy positions with fixed bayonets. With utter disregard for his own safety and completely ignoring the enemy fire, he rose to his feet in front of his battalion and with drawn pistol shouted to his men to follow him in the assault.”

The successful mission undertaken by the 101st Airborne Division to clear Carentan remains to this day one of the most exhilarating and famous war stories of the Allied invasion of Europe.

Very good article. Improved my knowledge of D, _Day

Improved my knowledge. Love the detail.

My step father was at Carentan. He won the Distinguished Service Cross. Wish I could get the article, but the site is blocking me.

George Heiner

Here is the citation:

ROSEMOND, ST. JULIEN P.

Citation:

The President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to St. Julien P. Rosemond (0-328203), Captain (Infantry), U.S. Army, for extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy while serving as Artillery Liaison Officer, Headquarters Battery, 377th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion, 101st Airborne Division, in action against enemy forces on 11 June 1944, in France. In the assault upon Carentan, the infantry battalion was pinned down by the intense enemy machine gun and rifle fire. Captain Rosemond as artillery liaison officer, in spite of this heavy enemy fire, moved to a forward position and directed artillery fire upon the enemy. He, though exposed to direct enemy fire, remained at his position until he accomplished his mission. Captain Rosemond, on the occasions of enemy counterattacks, repeatedly moved to a forward position in the face of heavy fire to direct artillery fire. The personal bravery, initiative and devotion to duty exhibited by Captain Rosemond exemplify the highest traditions of the military forces of the United States and reflect great credit upon himself, the 101st Airborne Division, and the United States Army.

Headquarters, First U.S. Army, General Orders No. 31 (July 1, 1944)

Home Town: Florida

A very brave man!

Excellent Article. My dad, then Captain Vito Pedone, was the co-pilot of the lead 9th Air Force Pathfinder Troop Carrier C-47A 42-93098, which was first to take-off from North Witham Airfield, England, to lead the Normandy airborne invasion across the English Channel to drop the first Stick of 101st AB Division Pathfinder Paratroopers into Drop Zone “A”, just before midnight on 5 June 1944. The lead pilot was Lt. Col. Joel Crouch. Since early 1943, Pedone and Crouch had trained the Pathfinder C-47 Pilots and the Pathfinder 101st & 82nd Paratroopers at their Pathfinder School at North Witham, preparing them for the D-Day airborne invasion of Normandy. My mother, First Lieutenant Jerry Curtis, one of the first Flight Nurses stationed in England in early 1943, and flew in the same C-47s into the Normandy beach head on 10 June 1944, to begin the evacuation of the severely wounded soldiers back across the channel to awaiting hospitals in England. I tell their story in an article “The D-Day Pilot and Flight Nurse”, which I prepared for the 75th Anniversary of D-Day, available on the D-Day Squadron website. Lt. Col. Stephen Pedone, USAF, Ret., Naples, FL.

Good article, but something didn’t add up when telling the exploits of Sgt Summers. “…Summers kicked in the door of the first one and shot 15 German artillerymen as they sat eating breakfast.” How come fifteen German soldiers were about to have breakfast like if they were on a peaceful environment, while there was a battle raging around them since hours ago?

I wondered about that, too.

It makes me happy that these stories continue in print for the succeeding generations to read and understand the importance of the word “freedom” and how bravely these men performed their duties with disregard to their own personal safety and future so we can live a peaceful life.

Many in this modern generation think our way of life has always been cookies and cream. My mother, a war bride from Germany made sure to tell me she wanted an American flag buried with her.