By Joshua Shepherd

Long before he attained fame as the co-commander of the Lewis and Clark expedition, William Clark was a discontented young lieutenant assigned to the U.S. Army’s 4th Sub-Legion. In the summer of 1794 Clark was engaged in his first campaign, a punitive expedition deep in the Northwest Territory, but was less than sanguine over the Army’s prospects. Indian forces had beaten the U.S. Army in the mystifying wilderness of the Ohio country twice before in 1790 and 1791. Clark, unsettled by what he considered the high command’s lethargic leadership, feared a reprise of such catastrophic defeat.

But on August 12, his spirits rallied. Clark’s journal entry for that day was full of effusive praise for the Army’s chief scout, an enigmatic frontiersman who was proving adept at wreaking havoc on the Indians. “Wells the Spie,” wrote Clark, returned to camp exhausted, bloodied, and leading a party of scouts that had ventured 50 miles behind enemy lines. More importantly, William Wells had brought back invaluable intelligence that would help shape American strategic planning. “This enterprising young man,” wrote Clark, had brazenly entered the enemy’s camp and successfully brought off two prisoners “from whome we learn the Situation and intention of the Enemey.”

On the perilously shifting borderlands of the early frontier, Wells was destined to become a living legend. Born in Pennsylvania and raised in Kentucky, young Wells’ frontier childhood was less than idyllic. By the age of 11 his mother had succumbed to sickness and his father was killed during a 1781 Indian ambush. Wells was cared for by family friends, but his tumultuous adolescence was far from over. In March 1784, Wells and three companions were abruptly surrounded by a party of Indians and taken captive. Although his friends eventually escaped, Wells was spirited into the heart of the Northwest Territory and taken to the Miami villages situated on the Eel River.

Wells readily acclimated to life with the tribes and was known as Apekonit, or Wild Carrot, a wry moniker given on account of his red hair. Eventually adopted by Gaviahatte, a prominent Miami chieftain, Wells was immersed in the warrior ethos of tribal culture and by his late teens was a willing participant in raiding parties that struck along the Ohio River. According to tradition, his exploits as a fighter garnered him a more fearsome name: Blacksnake.

His reputation as a warrior, paired with a fluency in English, ensured that Wells would become nearly invaluable on a violent frontier. He quickly earned the esteem of Little Turtle, war chief of the Miami and standard bearer of the hostile tribes of the Northwest Territory. The pair forged a lifelong bond; Wells served as a translator to the chief, married his daughter, and became a trusted counselor. By the late 1780s, his services as an interpreter brought him to the attention of American authorities, and his white family was informed of his whereabouts. His older brothers Carty and Samuel met with William but failed to convince him to return to Kentucky.

Such painful choices would prove to be Wells’ unfortunate lot. In fall 1790, an American expedition under the command of Brig. Gen. Josiah Harmar targeted the principal Miami town of Kekionga, and on October 19 a strong detachment menaced Little Turtle’s village. Ambushed by warriors led by the war chief, the Americans fled in confusion. Three days later, a larger American column blundered badly at Kekionga and was nearly wrecked in a sharp fight that left Little Turtle master of the ground.

The following year would find a vengeful William Wells fully committed to the fight against the Americans. On August 8, 1791, a diversionary raid mounted by Kentucky militia made a sweep along the Eel River, striking Wells’ home of Snake Fish Town. The bulk of the village’s warriors, including Wells, were absent, and the militia easily overran the settlement. The Kentuckians rounded up women and children who could be used as bargaining chips during negotiations with the tribes, and among the captives were one of Wells’ Indian wives and small child. Though a minor tactical success, the raid strategically backfired, further strengthening the position of the hostile faction among the natives.

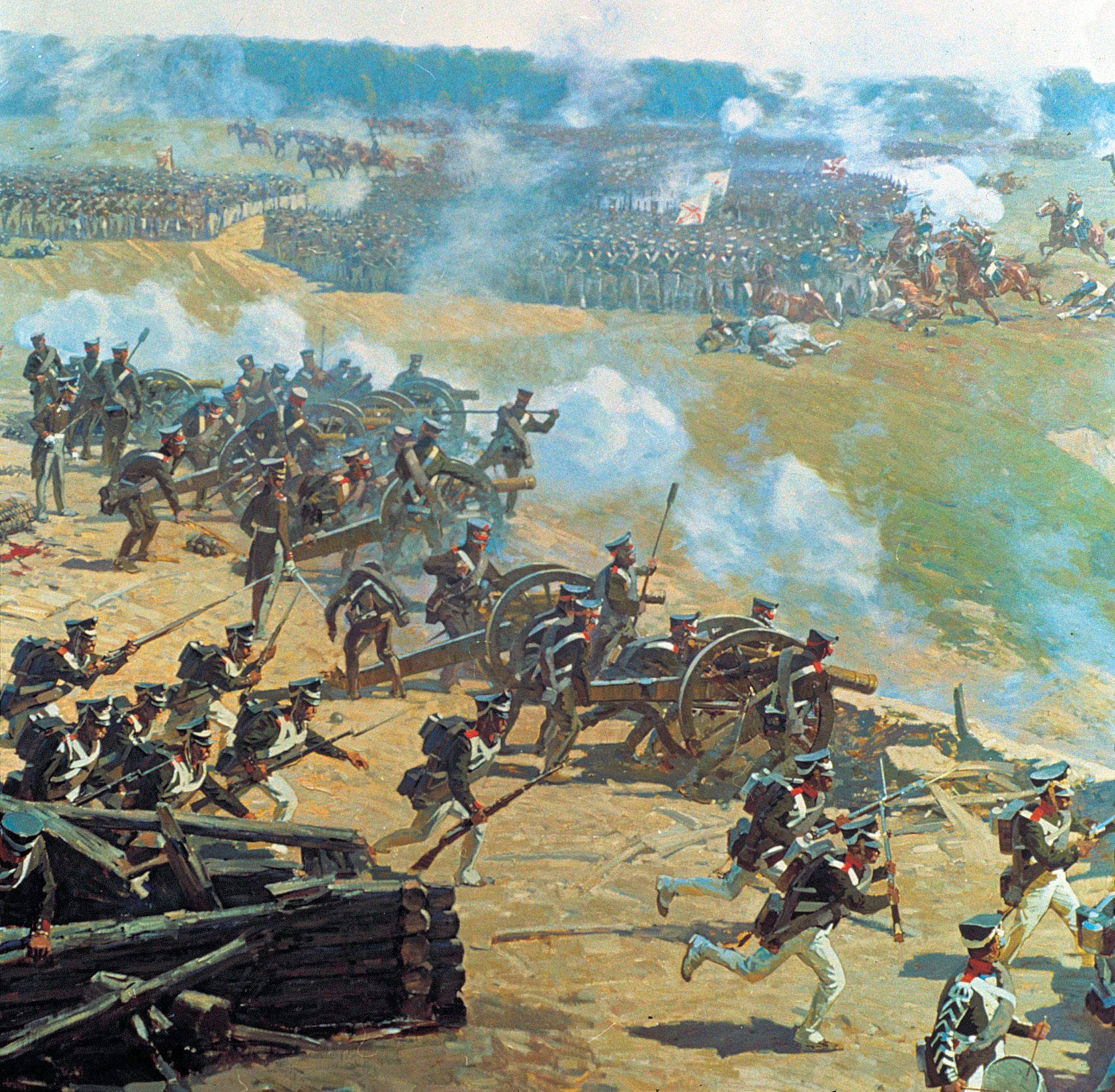

Shaken by the embarrassing Harmar debacle of the previous year, Congress authorized another expedition to be led by Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair. His grand plans would degenerate to utter disaster. Severe manpower shortages, unusually harsh weather, and frustrating supply shortfalls all served to demoralize an untrained rabble of volunteers. A complete lack of an effective intelligence network also crippled the American army as it groped its way north. By the evening of November 3, 1791, a befuddled St. Clair was certain that he was within 15 miles of his objective. But he actually was 60 miles from Kekionga. Worse yet, the woeful lack of intelligence deprived the general of a most crucial bit of information: Several miles to the north, more than 1,000 warriors were closing on the American position.

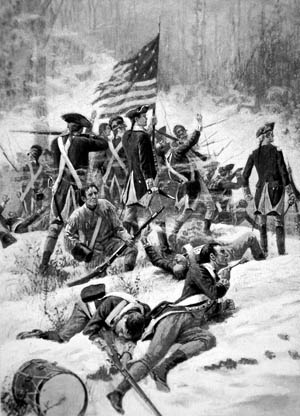

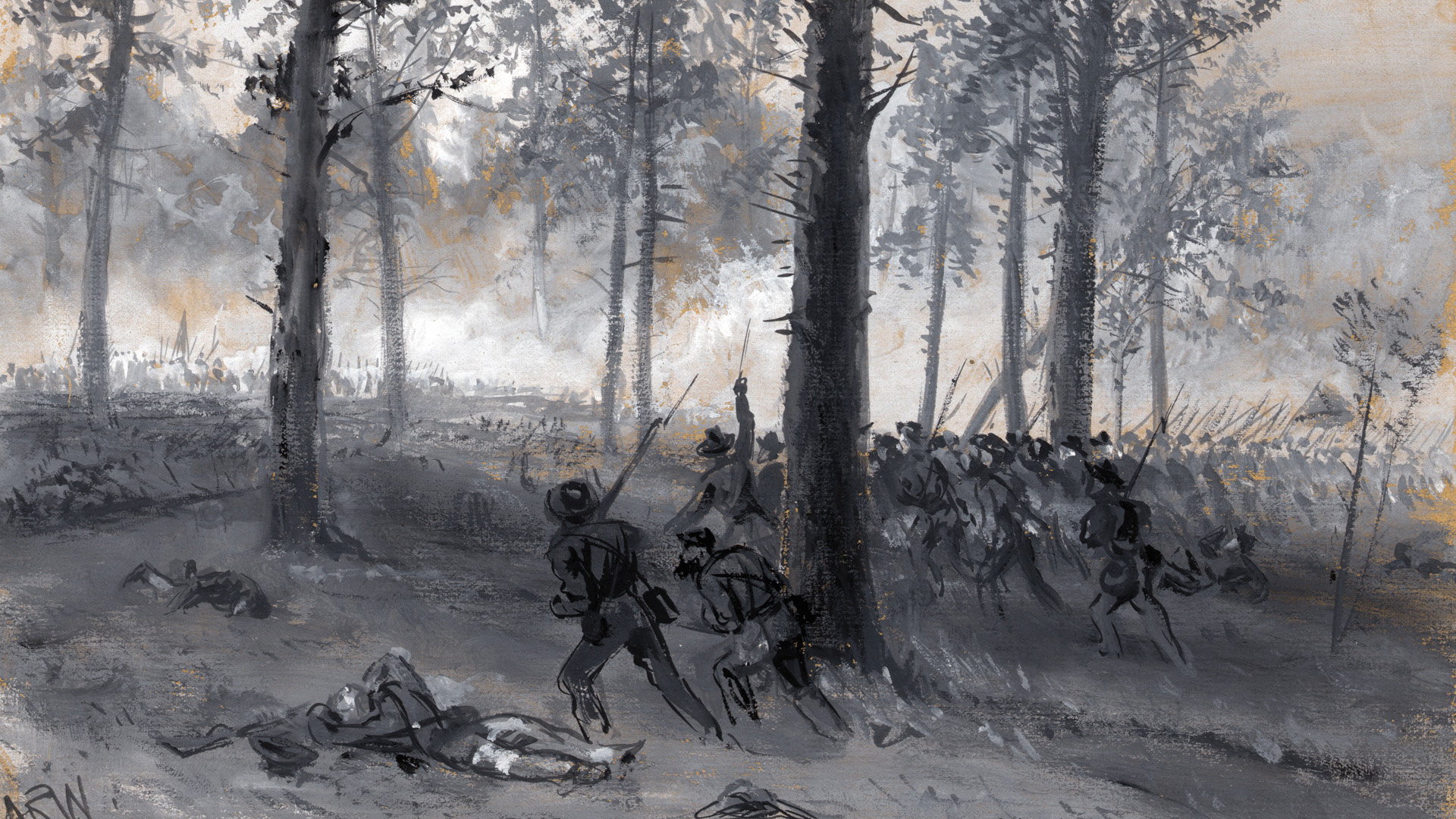

The Indians attacked St. Clair’s unprepared army at dawn the following day. To counter American superiority in firepower, Little Turtle placed a contingent of warriors under the command of William Wells, who was assigned the vital task of silencing the enemy artillery. The American gun crews suffered especially heavy casualties in the ensuing fight, and all but one artillery officer was killed. After three hours of savage fighting, St. Clair pulled out the battered remnants of his army. The battle constituted America’s most devastating defeat during the Indian wars. Approximately 630 men were killed and 280 wounded in the encounter. Wells later admitted that “he killed and scalped that day until he could not raise his arms to his head.”

In the spring of 1792, Wells was involved in negotiations to secure the release of Indian captives taken the previous summer, and he again met with his older brother Samuel, who had ironically been a company commander at St. Clair’s defeat. The elder brother persuaded William to visit his family in Louisville and, while there, Wells made the abrupt decision to return to civilization. Although he had spent the bulk of his formative years with the Miami, Wells later confessed that he had never been able to forget the pleasures of his childhood. He also hoped to secure a stable future for his family living in white society. Wells believed that he not only could earn a decent living but also make enough to tide him over during old age.

For a man destined to play the deadly game of frontier intelligence, old age was a remote likelihood. Wells, who was intimately acquainted with Indian culture and conversant in several languages, abruptly found himself in high demand to the American war machine. For the sum of $300, Federal authorities secured the services of Wells, who was tasked with transmitting messages and gathering intelligence in the Indian camps. Although Wells did not openly espouse the American cause, his increased contact with the Americans brought him under mounting suspicion. “He was suspected by many of the chiefs to be a spy, and frequently in danger of losing his life,” wrote Major John Hamtramck.

whom were led by Indian scout William Wells.

Exasperated by the bloody stalemate in the Northwest, President George Washington selected a new army commander, Maj. Gen. “Mad” Anthony Wayne, to subdue the Indians once and for all. Though an impetuous field commander, Wayne was a methodical planner who possessed a keen eye for detail. He undertook the complete reorganization of the army, which he christened the Legion of the United States, and organized a functioning intelligence network, the lack of which had gravely crippled his predecessors. The general incorporated three scouting companies to gather intelligence on enemy dispositions and seize prisoners for interrogation.

Seeing in Wells a latent talent for such clandestine work, Wayne gave him command of one of the scout companies. The general, who relied heavily on Wells as his chief intelligence gatherer, routinely assigned the most difficult missions to Wells’ company, and for good reason. To fill out the ranks of his detachment, Wells chose only the best, selecting an experienced set of frontiersmen who could beat the Indians at their own game. The dangerous service they would perform had its rewards. Wells’ men were authorized to requisition any dragoon mount of their choice and were likewise allowed more than their share of whiskey. All in all, noted fellow scout John McDonald, they “were confidential and privileged gentlemen in camp.”

Wayne was intent on regularly capturing prisoners for intelligence purposes, a task for which Wells proved particularly adept. His men, who dressed and painted themselves as Indian warriors, operated with near impunity behind enemy lines. “His knowledge of the Country & of the Indian Habits & Mode of Warfare,” wrote Captain William Henry Harrison, “were indispensable to the Success of our operations.” Wells’ prowess at such irregular operations drew the ire of the tribes, who came to regard him as the worst sort of traitor. By 1794, frustrated native leaders requested assistance from British authorities in dealing with the scout, lamenting that Wells had repeatedly created havoc for them.

When Wayne prepared for a final push down the Maumee Valley that summer, the general was desperate for fresh intelligence and, as usual, assigned Wells the difficult mission of seizing a prisoner. On August 11, Wells and five of his men captured a Shawnee warrior and his wife. While returning with their captives, Wells spotted an Indian campsite and remarkably decided to press his luck. Brazenly riding into the Delaware camp, he struck up small talk with the Indians, who were initially oblivious to the identity of the newcomers. When the scouts were finally recognized as American spies, bedlam erupted. Both sides opened fire and dashed for cover; in the confusion, the Americans escaped. As the scouts sped away, Wells was struck by a ball that shattered his wrist. Although attended by an army surgeon, it was clear that Wayne’s most trusted spy was unfit for further field operations.

Despite his incapacitating wound, Wells made a vital contribution to American strategic planning. By August 17, 1794, Wayne had his legion on the north bank of the Maumee River within striking distance of the Indians, who had formed up at Fallen Timbers, a tangled swath of forest that had been felled by a storm. While subordinate officers pled for an immediate attack, Wayne uncharacteristically demurred; intelligence from his most trusted scout seems to have played a part in his reasoning. The Indians traditionally fasted before battle, Wells explained, and an unexpected delay to the fighting would weaken the enemy. British observer John Norton later reported the debilitating effects of the extended fast. Many of the warriors, “to alleviate the sufferings [of hunger], did not hasten to take their stations, but remained in the encampment,” he wrote.

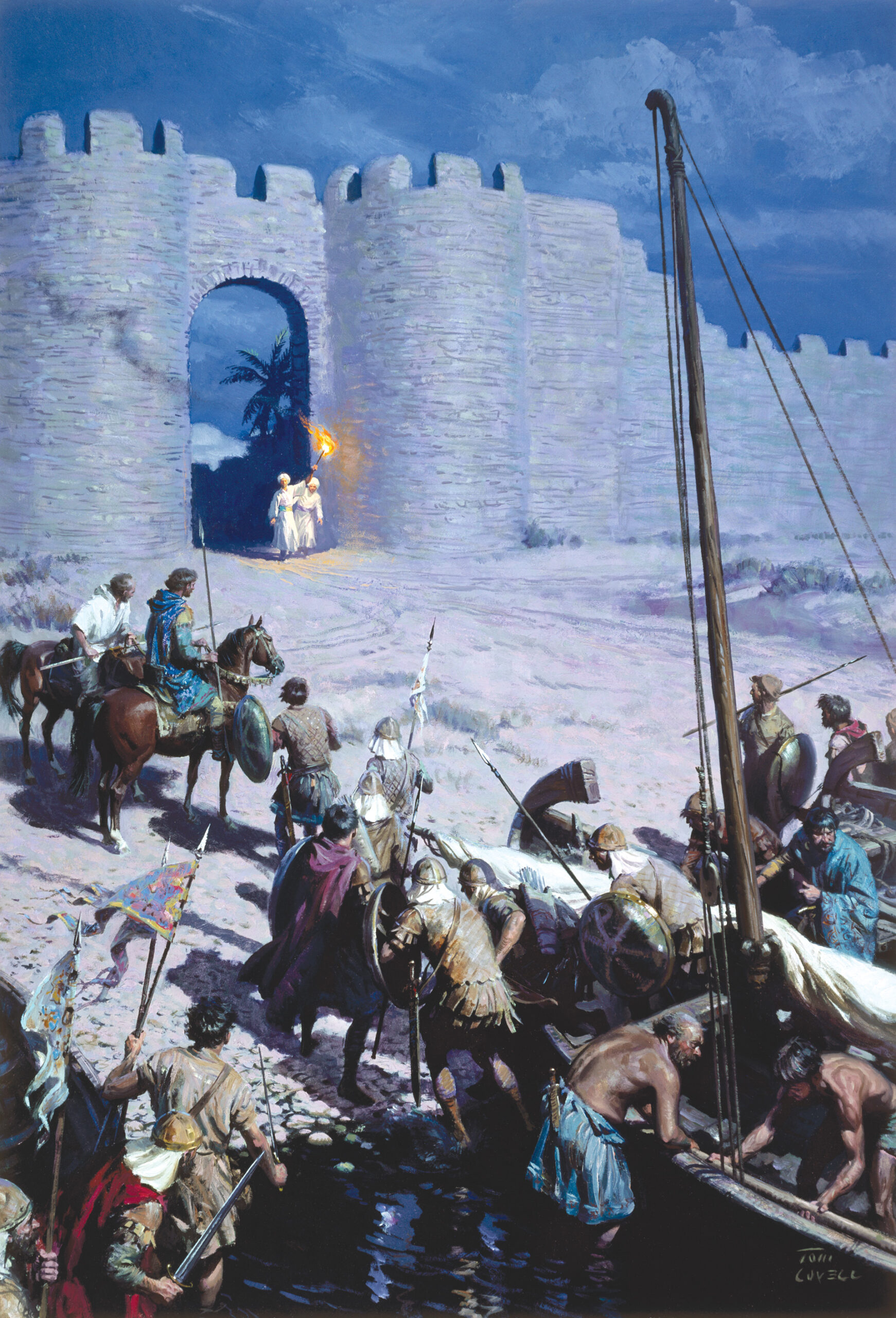

Wayne’s decision paid off. On the morning of August 20, the legion crashed into the Indian lines at Fallen Timbers. As their position collapsed, dozens of warriors were shot or bayoneted as they frantically scrambled to escape the killing ground. Unopposed, Wayne marched the legion up the Maumee Valley, laying waste to Indian settlements and crops in his path. The destruction finally halted at Kekionga, where Wayne forever prostrated the Miami by erecting Fort Wayne on the site of their former capital.

Shattered in the devastating fight at Fallen Timbers, the Indian confederacy sued for peace the following summer and opened negotiations with Wayne at Fort Greenville. Largely recovered from the wound to his wrist, Wells served as translator at the negotiations, which concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Greenville on August 3, 1795. By the stroke of a pen, the tribes ceded 25,000 square miles. Not until August 12 did a reluctant Little Turtle affix his signature to the document. “I am the last of the chiefs to sign this peace with the Americans, so also will I be the last to break the agreement,” he wrote.

Appointed Indian agent in Fort Wayne, Wells succeeded in securing a good measure of financial stability. For his invaluable intelligence services before the Treaty of Greenville, he had been paid well, receiving some $2,000. His salary netted him about $600, and Wells likewise gained title to 320 acres of prime bottom ground near Fort Wayne. Such wealth contributed to William Wells’ fall from favor with government authorities. His chief antagonist was John Johnston, the manager of the Federal trading post at Fort Wayne. Johnston was convinced, perhaps for good reason, that Wells’ management of the Fort Wayne Agency was tainted by malfeasance and rampant graft. Johnston forwarded an avalanche of regular accusations to Wells’ superiors in the War Department.

Matters were further complicated by Wells’ opposition to official policy. Beginning in 1803, the Indiana territorial governor, William Henry Harrison, who exercised nominal supervision of Wells’ duties, instituted an aggressive program of territorial expansion. During the following six years, Harrison concluded eight treaties with the tribes and purchased 50 million acres of land at the astounding rate of less than two cents per acre. Harrison expected Wells’ influence with the Indians to bolster the government’s bargaining position, but the agent found it difficult to support treaties that he felt were little more than heavy-handed and inequitable land grabs.

His close ties to Little Turtle likewise raised eyebrows. Although the Miami chief remained a staunch advocate of peace, he was a vocal opponent of Harrison’s expansionist policies. The tremendous influence that Wells and Little Turtle wielded in the tribes was nothing short of alarming, and Harrison requested that the War Department order greater “unanimity of purpose” from the Fort Wayne Agency. Harrison had known Wells since his days as a spy for Wayne and felt that the habits of subterfuge which he had learned in the intelligence business were a grave threat to stable Indian relations. “My knowledge of his character, induces me to believe that … much mischief may ensue from his knowledge of the Indians, his cunning and his perseverance,” wrote Harrison

While American officials frittered away valuable time with such infighting, Wells found that he was a lone voice concerning the mounting threat posed by the rise of the Shawnee leader Tecumseh and his brother the Prophet. Although the duo publicly avowed peace, Wells’ Indian informants indicated that the brothers were privately preparing for a renewal of hostilities by promoting an unprecedented pan-Indian confederacy. Wells informed the War Department that the tribes were growing “religiously mad” in their devotion to the Prophet and that “it is to be feared that his intentions are not friendly.” For his part, John Johnston inexplicably characterized the Prophet as not only harmless but a likely American ally.

Such feuding resulted in Wells’ removal from office in 1809. A pleased Johnston replaced him as head of the Fort Wayne Agency, but it became increasingly apparent that Johnston’s utopian descriptions of a peaceful frontier were preposterous. By 1811, Governor Harrison, who by that point was preparing for a military strike against the Prophet’s followers, was given authorization to reinstate Wells. In September he did just that, albeit appointing Wells as sub-agent to the Miami tribe alone. Two months later, Harrison’s army secured a narrow tactical victory at the Battle of Tippecanoe but was severely mauled in the process.

It was an inauspicious beginning to renewed hostilities. War was officially declared between the United States and Great Britain on June 18, 1812, and the young republic found itself woefully unprepared for such a contest. Fort Mackinac fell to the British on July 17, and American forces at Detroit were soon reeling before a British counterthrust. Informed that Fort Dearborn at Chicago was ordered abandoned, Wells set out to assist in the evacuation.

He had personal reasons for doing so, one of which was that his niece Rebekah was married to the post’s commander, Captain Nathan Heald. When he arrived at Fort Dearborn, the installation was already surrounded by hundreds of hostile Pottawatomie. The Americans destroyed stockpiles of powder and liquor, which further infuriated the Indians, and subsequent negotiations for a peaceful evacuation of the garrison went badly. On the morning of August 15, 1812, Heald, determined to obey orders, led the garrison out of the stockade. William Wells, sternly resigned to the inevitable, dressed as a Miami warrior and blackened his face—a tribal tradition reserved for condemned men.

Not a half hour after the column left the fort, the Indians unleashed the attack that Wells expected. Heald’s regulars gave a good accounting of themselves but were ultimately overwhelmed. Wells, agreed eyewitnesses, went down fighting. Pinned beneath his horse, the wounded Indian agent defiantly exchanged angry words with the enemy until contemptuously telling them to “shoot away.” Little mercy was shown the man whom the Pottawatomie regarded as a traitor: Wells was shot to death, mutilated, and beheaded. In grim testament to his prowess as a great warrior, the Indians cut out Wells’ heart to be devoured in ritual cannibalism. It was a grisly frontier rite in which participants hoped to absorb the bravery of the fallen. “Each Indian coming along, took a bite of it,” said the Pottawatomie warrior Benac.

His death left a vacancy in the Indian Agency that was impossible to fill. But on a rapidly changing frontier, Wells’ conflicted loyalties to the United States and the Miami tribe rendered him a tragically doomed figure. Unable to entirely assimilate in either white or native culture, Wells was valued by both but not entirely trusted by either. Ironically, the greatest compliment paid to Wells was that offered by his old nemesis John Johnston. Reflecting on the legacy of the frontier scout that he had come to despise, Johnston could not help but offer grudging admiration for the defining nature of Wells’ character. “He was a brave and reckless man,” said Johnston, “and had the greatest contempt of death.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments