By Jeff Chrisman

The first time Adolf Hitler ventured into the captured territory of the Soviet Union was six weeks into the campaign on August 4, 1941, when he traveled to Borisov to the headquarters of Army Group Center and its commander, Field Marshal Fedor von Bock. Colonel General Heinz Guderian, commander of the Army Group’s Panzer Group 2, whose troops had spent those seven weeks slashing through the western Soviet Union, had been called to the headquarters to make a report to the Führer.

During their meeting, Hitler spoke of his indecision regarding the further course of the campaign. He said that Leningrad was the campaign’s primary objective at this point because of its industrial capacity. But he was not sure whether Moscow or Ukraine would come next. Later, Guderian wrote, “He seemed to incline toward the latter target for a number of reasons: first, Army Group South seemed to be laying the groundwork for victory in that area; secondly, he believed that the raw materials and agricultural produce of the Ukraine were necessary to Germany for the further prosecution of the war; and finally, he thought it essential that the Crimea, ‘that Soviet aircraft carrier operating against the Rumanian oilfields’ be neutralized.”

On the flight back to his own headquarters, Guderian decided he would make preparations based on a continuation of the attack toward Moscow, which was the course he thought to be best and he knew that it was the priority for Field Marshal Walter von Brauchitsch, commander in chief of the Army, Army Chief of Staff Colonel General Franz Halder, and Field Marshal von Bock. At that point the troops on the panzer group’s north flank were in heavy combat in the Yelna salient east of Smolensk, while on the south flank they had just encircled several Soviet divisions in Roslavl, 425 miles from their start on June 22 and 225 miles from Moscow.

On July 19, Hitler had issued Directive 33, ordering Army Group Center to continue its advance toward Moscow with only infantry units and to turn its armored units to the north toward Leningrad and to the south toward Ukraine, unleashing a storm of controversy. Over the next five weeks, what had been a simmering bone of contention flared into open controversy. Halder pleaded for a continuation of the attack toward Moscow, believing that diversions to the north and south would only bog his troops down in positional warfare. Bock also lobbied for Moscow, supported by Guderian and Col. Gen. Hermann Hoth, commander of Army Group Center’s other armored spearhead, Panzer Group 3. All three firmly believed that the only way to defeat the Soviet Union was to capture its capital, the central hub of the entire nation, before year’s end.

On August 12, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, commander of the armed forces, issued an order confirming the intention of removing the armored units from Army Group Center for use in attacks to the north and south. On the 18th, Halder and von Brauchitsch sent a long memorandum to Hitler thoroughly explaining their objections. Hitler stood firm. Halder suggested to von Brauchitsch that they resign in protest, but von Brauchitsch vacillated. They did not resign. Ironically, on the other side of the front line Soviet Marshal Josef Stalin was enduring a similar struggle.

Toward the end of July, General Georgi Zhukov, chief of staff of the Red Army, had reported to Stalin that a continued German advance from Smolensk toward Moscow was unlikely. He said German losses at Smolensk had been heavy and they had no available reserve. He therefore suggested that some of the units in front of Moscow should be transferred to other, more threatened sectors. Stalin flatly refused. He was sure that Moscow was Hitler’s primary target and would not even consider lessening its protection.

As he was concluding his remarks, Zhukov struck what turned out to be another tender spot when he said that Kiev would have to be surrendered. Stalin would not even think of surrendering Kiev, the third most populous city in the Soviet Union. He saw Zhukov’s words as an indication that he had lost his nerve and removed him from his position as chief of staff. Fortunately for the Soviets, Stalin assigned Zhukov to command the Reserve Front rather than having him shot, as had been his previous practice.

On August 12, Stalin appointed Lt. Gen. Andrei Eremenko to command the new Briansk Front composed of the Fiftieth and Thirteenth Armies and gave him specific orders to prepare to stop the renewed German offensive against Moscow, which was expected soon. Zhukov, though no longer chief of staff, kept himself fully informed about the overall situation. When he learned that recent prisoner interrogations indicated that Army Group Center had indeed gone over to the defensive on the approaches to Moscow he became alarmed.

Zhukov wired Stalin on August 19 and reiterated his concerns in light of recent events. In his reply, Stalin agreed with Zhukov that enemy operations indicated a potential threat to the Southwestern Front in Ukraine, but he said that resolute measures were being undertaken to prevent that. Stalin also restated his resolve to hold Kiev. Col. Gen. Mikhail Kirponos, commander of the Southwestern Front, agreed with Stalin. He could and would successfully defend Ukraine.

Army Group Center’s Second Army, which was attacking eastward on Panzer Group 2’s right flank, had not been able to keep pace with the motorized units of the panzer group. During the first week of August, Second Army’s easternmost units were attacking near Cherikov on the Sosh River, almost 100 miles southwest of Guderian’s units fighting on the Desna River east of Roslavl. Therefore, the panzer group’s XXIV Motorized Corps spent the next three weeks cleaning up pockets of enemy troops on its southern and southwestern flanks, eliminating the threat and enabling the Second Army to catch up. This brought Panzer Group 2’s units farther south. Whether they would continue in that direction or turn to the northeast toward Moscow was still up in the air.

On the 23rd, Guderian, as well as all the Army commanders subordinated to Army Group Center, were summoned to a conference at army group headquarters with von Bock and Halder. Fourth Army’s Field Marshal Hans von Kluge, Second Army commander Col. Gen. Maximilian von Weichs, commander of the Ninth Army Colonel General Adolf Strauss, and the panzer leaders Guderian and Hoth were gathered in the conference room when von Bock and a dour looking Halder walked in.

“The Führer has decided to conduct neither the operation against Leningrad as previously envisaged by him, nor the offensive against Moscow as proposed by the Army General Staff, but to take possession first of the Ukraine and the Crimea,” Halder announced.

The generals were stunned!

“What can we do against this decision?” asked von Bock. “Nothing. It’s immutable,” Halder replied. There it was, the decision that they all feared and fought had been made.

But maybe there was something they could do. Bock suggested that Guderian accompany Halder back to the Führer’s headquarters in East Prussia and try to convince Hitler to change his mind. They had to try something.

Guderian and Halder arrived at the headquarters about 8 on that Saturday evening; Halder went to check on arrangements for a meeting with Hitler while Guderian reported to von Brauchitsch. Guderian was floored when von Brauchitsch greeted him with the words, “I forbid you to mention the question of Moscow to the Führer. The operation to the south has been ordered. The problem now is simply how it is to be carried out. Discussion is pointless!”

Guderian thought the meeting was, therefore, pointless, but the army commander insisted, make your report, but no mention of Moscow.

Several members of the Führer’s staff were present in the map room, including Keitel; General Alfred Jodl, chief of the operations staff of the armed forces; Colonel Rudolf Schmundt, Hitler’s chief adjutant; and many others but neither Halder nor von Brauchitsch. Guderian was on his own.

Hitler greeted the panzer leader cordially and asked for his report. Guderian spoke about the current situation, the condition of his troops and their equipment, about the supply situation and Russian resistance.

“Do you believe your troops are still capable of a major effort?” Hitler inquired.

Guderian saw his opening. “If the troops are set a great objective, the kind that would inspire every man of them, yes.”

“You are, of course, thinking of Moscow,” Hitler replied.

“Yes my Führer, may I have permission to give my reasons?”

“By all means Guderian. Say whatever is on your mind.”

General Guderian began slowly, laying out the detail he had organized on the plane:

Moscow was the head and heart of the Soviet Union …

It’s the communications center …

It’s the political brain …

It’s an important industrial area in its own right …

It’s the transportation hub of the empire …

It’s the only place Stalin would never

abandon …

It’s where the Red Army would stand and fight … and be destroyed.

The season and the weather were running out …

The troops’ morale …

The orders and plans are ready …

Hitler listened quietly, and when Guderian finished he walked over to the map, put a hand on Ukraine, and launched into a lecture justifying his intention to attack there first.

The conference broke up around midnight. Guderian strode out of the Wolf’s Lair toward what would be the last victory in his long career. Guderian was the man who would be acknowledged as the creator of the German panzer forces in the 1930s. Western journalists coined the term “Blitzkrieg” to describe Guderian’s plunge through Poland in 1939 and France in 1940. It was now 1941, and his troops had just cut through the western Soviet Union in a similar fashion and were set to encircle the enemy’s capital. But first, there would be a diversion to the south, through the Ukraine.

In a quick call before leaving East Prussia, Guderian told his chief of operations, Lt. Col. Fritz Bayerlein, the news. This meant a suitably forlorn staff when the general arrived back at his headquarters. “There was nothing I could do, gentlemen, I had to give in,” he told the assembled group upon his return. Halder and von Brauchitsch had left him out to dry, alone in front of Hitler and his entourage. Interestingly enough, when Guderian arrived back at his headquarters well after midnight, Halder’s order for the attack was waiting for him, having arrived well before his meeting with Hitler.

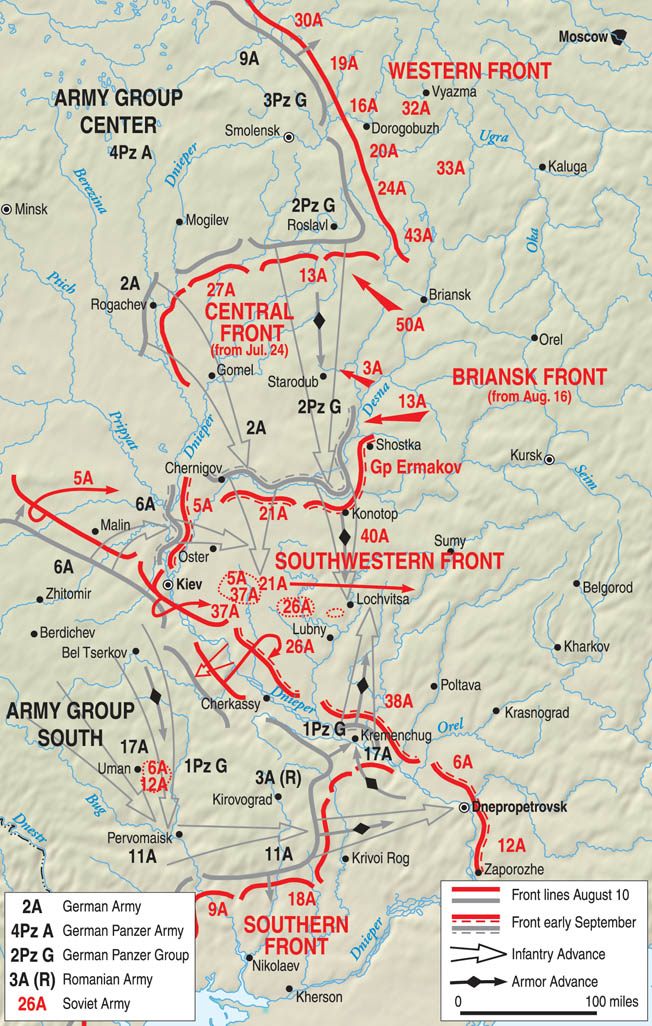

The plan the German generals quickly developed was straightforward. Panzer Group 2 would continue south through eastern Ukraine and meet troops from Army Group South about 120 miles east of Kiev. Second Army would move south on the panzer group’s right flank and provide a tight seal on the north side of the forming pocket. Army Group South’s 17th Army, which was at that point closing up to the Dnieper River southeast of Kiev, would forge a bridgehead over the Dnieper near Kremenchug, about 150 miles southeast of Kiev. Panzer Group 1, Army Group South’s armored strike force, would then advance northeast out of that bridgehead and meet Panzer Group 2’s attack, closing and holding the eastern side of the pocket. Then the Sixth Army, currently holding the western side of the Dnieper north and south of Kiev, would crush Kiev and liquidate the pocket.

At the last minute Guderian had to give up his strongest corps, the XLVI Motorized Corps. Halder had it transferred to Army Group Center reserve on the eve of the attack in an attempt to husband it for his favored attack toward Moscow. This left the panzer group with only the XXIV Motorized Corps and the XLVII Motorized Corps.

All units of the panzer group were badly in need of rest and repairs. There had not been a break since the campaign began. The weather was hot and muggy between thunderous downpours. The best of the roads were compacted dirt that quickly turned into quagmires of deep mud when it rained. And when it did not rain there was the dust! Great clouds of dust hung over the march routes, stirred up by anything that moved and so fine that it penetrated clothing, coating the troops’ sweating bodies. Engines broke down because their air filters could not keep out the dust. But the capture of Ukraine would not wait.

Assignments for the attack depended to a great extent on a unit’s current location. The XXIV Motorized Corps units—3rd Panzer Division, 4th Panzer Division, and 10th Motorized Division—having been engaged for the last few weeks in eliminating pockets on the army’s southwestern flank, would lead the attack south on the army’s right flank while XLVII Motorized Corps units—17th Panzer Division, 18th Panzer Division, and the 29th Motorized Division—would cover the east. The attack would start on August 25 with the town of Konotop the first objective. After that, specific objectives would be decided on the road according to results achieved.

On August 24, Marshal Boris Shaposhnikov, Stalin’s new chief of staff, informed Eremenko that his Briansk Front could expect Guderian’s main blow to fall on its northern flank, first toward Briansk and then toward Moscow, probably the next day. Guderian’s main blow did fall the next day. But it was on the front’s southern flank toward Ukraine, not toward Moscow.

At first light on the 25th, Guderian set out for the headquarters of the 17th Panzer Division near Pochep on the panzer group’s left, or eastern, flank. That flank was sparsely held, and Guderian wanted to make sure the division was fully informed as to its critical role. Unfortunately, before he could reach the division his command car and several vehicles of his column broke down completely due to poor road conditions.

General Walter Model, commander of the 3rd Panzer Division, XXIV Motorized Corps’ spearhead, had reorganized his division into three balanced battle groups after the capture of Novozybkhov and was thrusting southeastward toward Novgorod-Seversk on the afternoon of the 25th. Aerial reconnaissance had determined that the bridges over the Desna River were still intact. It was imperative that at least one of those bridges be captured. Time was of the essence. About 5 pm, the lead battle group (Kampfgruppe), Kampfgruppe von Lewinski, three kilometers short of the Desna River, ran up against the first Soviet defensive positions.

Lieutenant Colonel Werner von Lewinski, commander of the division’s 6th Panzer Regiment, called a halt to confer with his subordinates in a nearby ravine. Enemy observation aircraft circled overhead. General Model arrived to join the meeting. Just then the Soviet artillery fire escalated. Model was wounded in the hand, Colonel Gottfried Ries, commander of the division’s artillery regiment, and several staff officers were killed. Model had no alternative but to pull back, await the remainder of the division, and prepare an attack for the morning.

During the 25th the 10th Motorized Division, on the XXIV Motorized Corps’ right flank, was moving south. There were small pockets of determined resistance and roving groups of enemy troops who had been cut off from their headquarters. The division had captured Klinzy against light resistance on the 24th and was now moving toward Semenovka and Cholmy. The 4th Panzer Division, which had been clearing enemy pockets around Unecha, was now maneuvering south as well and began meeting stiff resistance as it approached Starodub, 45 miles north of Novgorod-Seversk.

Guderian did not reach the 17th Panzer Division headquarters near Pochep until mid-afternoon, just ahead of the XLVII Motorized Corps commander, General Joachim Lemelsen. Guderian was worried that the forces assigned to him for flank protection (XLVII Motorized Corps) were insufficient to handle the task and maintain the pace of the XXIV Motorized Corps as it plunged south into Ukraine. Guderian had requested the return of the XLVI Motorized Corps but had been rebuffed. He explained his concerns to General Wilhelm Ritter von Thoma, commander of the 17th Panzer Division, and General Lemelsen. Both men understood and were confident that they could maintain their advance along with the XXIV Motorized Corps. Guderian spent the night in Pochep so he could observe the division’s attack in the morning.

Lemelsen also updated Guderian on the positions of the other corps units. The 29th Motorized Division was clearing the western bank of the Sudost River north of Pochep and waiting for relieving units from Fourth Army. The 18th Panzer Division was regrouping, having been spread out during the fighting for Roslavl.

At 5 am on the 26th, the renewed 3rd Panzer Division attack on Novgorod-Seversk began with the three combined arms battle groups attacking from different directions. Artillery fire rained down on the lead elements as they approached the first positions, but now their own artillery was able to respond. The first roadblock was overrun. Maps indicated that the bridge over the Desna was at the northern entrance to the city. The advanced guard was soon at the northern entrance, but there was no bridge.

At about that time, Lt. Col. Gustav-Albrecht Schmidt-Ott reached the high ground northeast of the city with his 1st Battalion, Panzer Regiment 6. The broad valley of the Desna spread out before them, on their right the city and beyond that the high wooden road bridge over the Desna with a never-ending stream of vehicles fleeing eastward. Schmidt-Ott immediately ordered an attack.

By 10 am the lead tanks reached the foot of the 875-yard-long wooden bridge. Suddenly, machine-gun and rifle fire erupted from two guard houses on the near end of the bridge. Artillery and mortar shells from the far bank began to fall. Tanks of the advanced guard opened up and quickly destroyed both guard houses. A German engineer vehicle roared up, and several men scampered under the bridge to remove demolition charges.

The tankers knew the bridge could go up at any minute. The tanks, firing at anything that moved, reached the far end of the bridge, and the shocked Soviet riflemen fled their positions. Tanks and half-tracks rushed across; engineers were rapidly cutting wires. Success! The panzer group had breached the Desna River. General Model immediately ordered his entire division over the bridge with the 10th Motorized Division securing the rear.

Guderian received the news just after he had left the 17th Panzer Division operation on the east side of the Sudost River south of Pochep. Earlier he had diverted the 4th Panzer Division to the left flank to deal with Soviet forces gathering near the confluence of the Sudost and the Desna, southeast of Pogar. They would temporarily fill the gap between the 17th Panzer Division bridgehead at Pochep and the 3rd Panzer Division bridgehead at Novgorod-Seversk. There was little else Guderian could do until Second Army units arrived from the west or Fourth Army units arrived from the north to relieve his units.

In late afternoon, the 4th Panzer Division moved into Kister, a small city near the confluence of the two rivers, in open combat formation and met significant Soviet forces. General von Langermann’s troops spent the remainder of that day and most of the next in difficult house-to-house combat, eliminating that threat to the panzer group’s flank.

Guderian’s headquarters had moved to Unecha during the day, and he arrived there just before midnight.

On the 27th, most units remained in contact with the enemy. The 17th Panzer Division was fighting near Semtsy, 7.5 miles south of Pochep; the 3rd Panzer Division was defending and enlarging its bridgehead south of Novgorod-Seversk, the 4th Panzer Division was engaged in heavy combat near Kister, and the 29th Motorized Division was covering the panzer group’s deep eastern flank between Shukovka and Pochep. The 10th Motorized Division now covered the western flank near Cholmy. The 18th Panzer Division had finally gotten clear of Roslavl but was strung out on the road from there to Mglin.

Operations were mostly suspended the next day when early downpours created a sea of mud. By this time the Second Army was approaching the Desna River east of Chernigov. The boundary between Second Army and Panzer Group 2 was established as the line Surash-Klinzy-Klimovo-Cholmy–Sosnitza.

Sunrise on the 29th found virtually all units under Soviet air attack. During the next week the Soviets threw more than 4,000 ground attack and bomber sorties against the panzer group. Soviet units desperate to withdraw to the east undertook several vigorous and coordinated attacks against the panzer group’s spearhead.

The 10th Motorized Division, having crossed the lower Desna, was leading on the panzer group’s west flank and approaching the Kiev-Moscow railroad west of Konotop when it came under heavy attack to its front and right flank. The situation became so dire at one point that the division’s bakery company had to drop its aprons and pick up its rifles. But the division still had to pull its forward units back across the Desna temporarily to stabilize the situation. The lead elements of the 3rd Panzer Division were also under extreme pressure at Shostka and Voronezh on the east side of the Desna. Voronezh had to be evacuated, but Shostka held.

The 17th Panzer Division was struggling to clear the east side of the Sudost south of Pochep. Once units of the Fourth Army had taken over for the 29th Motorized Division along the eastern flank south of Zukovka it was moved through the Novgorod-Seversk bridgehead to the east side of the Desna and turned north to relieve some of the pressure on the 17th Panzer Division. The 18th Panzer Division had finally begun to arrive and was replacing the 4th Panzer Division while clearing up the enemy on the west side of the Sudost near Kister. After it was relieved, the 4th began shifting to Novgorod-Serversk, but its maneuvering was limited due to lack of fuel.

Once again General Guderian became concerned about his flank, but this time it was his west flank. He flew to XXIV Motorized Corps headquarters and told General von Geyr to spend the 30th liquidating the threat to his west flank. He could then resume his advance to the south on the 31st.

Guderian repeated his appeal for enough troops to do the job and pleaded for the return of the XLVI Motorized Corps. This time his entreaties bore fruit, if only grudgingly. Initially, only the Infantry Regiment Grossdeutschland was released to him on the 30th. Guderian needed the whole corps, but it was not available. On September 1, Army Group Center added the 1st Cavalry Division and on the 2nd came the 2nd SS Division Das Reich. Finally, the XLVI Motorized Corps headquarters arrived.

On the Army Group South front, 17th Army units made several assault crossings of the Dneiper River near Kremenchug, 160 miles southeast of Kiev, on the morning of August 29. They quickly enlarged and fortified their bridgehead against pressure from the Soviet 38th Army’s units nearby.

On the 30th, Stalin ordered the new Briansk Front to attack from the Sevsk area toward Starodub and Guderian’s spearhead. However, because it was still ordered to guard against an attack on Moscow, its efforts were more aimed at keeping Guderian from turning east than preventing his moving south. These attacks hit hard, but 3rd Panzer Division units were able to more or less fend them off and continue southward. The Germans did, however, recognize the threat to their left wing and leave forces to protect it.

The more immediate concern for the 3rd Panzer Division on the 30th was the Soviet force attacking its western flank. Lokotki and Schostka were hit in the morning from a dense wooded area to the west. Several 52-ton KV-1 tanks, against which the German antitank guns were powerless, threatened to overrun positions there until individual artillery pieces were brought forward to fire on the Soviet giants over open sites.

The next day, 4th Panzer Division tanks struck south-southwest from the Novgorod-Seversk bridgehead into the north flank of the enemy concentration in the wooded area and destroyed the threat. By evening on the 2nd, reconnaissance elements of the 3rd Panzer Division had pushed south to just five miles north of Krolovetz. The surge to the south continued.

The Grossdeutschland Regiment began arriving on September 2 and was directed to Novgorod-Seversk to hold the bridgehead, freeing up more of the 3rd and 4th Panzer Divisions to continue the attack southward.

Guderian met the commander of the 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich, General Paul Hausser, in Avdeievka on September 3, informed him that 1st Cavalry Division would be coming up on his right flank in a day or two, and told him to be prepared to attack Sosnitza on the 4th.

Guderian next visited the 10th Motorized Division, which had been under extreme pressure and had suffered exceptionally high casualties fighting off attacks from the west. Over the past few days the division had been opposed by a greatly superior force of no less that four infantry divisions and a tank brigade. Guderian met with division commander General Friedrich von Loeper and praised him for his steadfast defense against such an overwhelming enemy force.

Pushing south along the east side of the Desna on September 2, the 3rd Panzer Division ran up against stiff resistance south of Voronezh. In the middle of a large wooded area with several lakes, the Soviets were holding the rail and road bridges over Essmany Creek, the only bridges for miles.

At mid-afternoon, after the division artillery had been brought forward and placed intense fire on the enemy positions, the reinforced 1st Battalion of Rifle Regiment 3 made an assault crossing of the creek and stormed the enemy positions. Simultaneously, the regiment’s 2nd Battalion, which had found a concealed crossing spot upstream, fell on the enemy positions from behind. The Soviets pulled back.

The 4th Panzer Division resumed the advance to the southwest and captured Zarevka on

September 3 against light resistance. It then encountered a Soviet column in Shernovka and destroyed it, taking 800 prisoners.

In the XLVII Motorized Corps sector on the 3rd, the 18th Panzer Division engaged a Soviet tank brigade at Trubchevsk and destroyed it, capturing four tanks intact and taking more than 1,000 prisoners. The 17th Panzer Division held the line of the Desna southwest of Trubchevsk to near Yevdokolye, and the 29th Motorized Division south from there to where the Sudost flows into the Desna. Since the beginning of the attack on August 25, the XLVII Motorized Corps had taken 17,000 prisoners, while the XXIV Motorized Corps had taken 13,000.

Guderian returned to his headquarters late, just as it started to rain again. He was a worried man, now more than ever. Not only were his flanks under heavy pressure, but his spearheads were meeting more and more resistance. The mud was making travel by wheeled vehicle virtually impossible. His panzer divisions had been reduced to half their original complement of tanks. Disabled vehicles littered the sides of every road they had traveled.

The next morning it had stopped raining, but it still took Guderian 41/2 hours to travel the 45 miles to the 4th Panzer Division’s front. The 4th was attacking Korop from the northeast and running into more determined resistance the closer it got. A Ju-87 Stuka dive bomber attack just after Guderian arrived loosened the defense, and Korop was captured later that afternoon. This allowed the 10th Motorized Division to shift to the west and fill the gap with the Das Reich at Sosnitza.

The corps commander, General Leo Geyr von Schweppenburg, was also with the 4th that day. He told Guderian that the 3rd Panzer Division had captured a map of Soviet dispositions and it indicated that his XXIV Motorized Corps was quite near the seam between the Soviet Thirteenth and Twenty-first Armies. The officers agreed that this presented an opportunity. Guderian then left for the 3rd Panzer Division to get Model’s thoughts on the matter.

Completely by accident, the 3rd had taken a notable prisoner on September 3. Soviet General Pavel Vasilevich Chistov, a holder of the Order of Lenin, had been dispatched from Moscow to oversee the establishment of defensive positions along the Desna River. He had more than a million workers at his disposal. He arrived by train in Novgorod-Seversk direct from Moscow that morning, completely unaware that the city was in German hands.

The 3rd Panzer Division had captured Krolovetz the night before and was moving south toward Spaskoye when Guderian reached it. Model agreed with Guderian as to the opportunity they faced and the need for speed to exploit it. A short time later word came from the advance guard that there were no serviceable bridges over the Seim River at Spaskoye. Unfortunately for the impatient Model, it took his division two days and attacks at three different locations to get across the Seim.

Behind the XXIV Motorized Corps spearhead and covering the lengthening eastern flank, the 18th Panzer Division was holding along the Desna at Trubchevsk, the 17th Panzer Division was holding south to the confluence with the Sudost River, the 29th Motorized Division was extending the line along the Desna to Novgorod-Seversk, and Grossdeutschland was holding from Novgorod-Seversk to Schostka and moving southeast toward Gluchov. On the west flank, the 1st Cavalry Division was patrolling the area behind Das Reich at Sosnitza north to Seminovka as units of the Second Army moved in from the northwest.

On September 6, Guderian drove to the Das Reich front southwest of Sosnitza. That afternoon, after heavy combat against a determined enemy, the division captured the railroad bridge over the Desna at Makoshino, just downstream from the confluence of the Seim and the Desna. Guderian told Hausser to enlarge the bridgehead as quickly as possible and to be prepared to attack eastward toward the south side of the Seim to help XXIV Corps units to cross that river.

Both of Guderian’s spearhead divisions were locked in heavy combat at the Seim River, the 4th Panzer Division at Baturin and the 3rd Panzer Division just upstream at Melnya. For the first few days of the offensive the spearhead divisions had usually met unorganized resistance from surprised units that were hastily brought together to oppose them. But for more than a week now the defense had been growing more and more stout every day. It now seemed that whichever way the Germans turned the enemy met them with combined arms attacks and artillery.

The 3rd Panzer Division approached the Seim River bridge in Melnya just before midnight on September 6, and just as they had been so many times recently, this bridge was blown up. This time, however, Colonel Oskar Audoersch, commander of the division’s 394th Rifle Regiment, was on the scene and immediately ordered his men into rubber rafts and across the river. Against heavy rifle and machine-gun fire the assault succeeded, thanks in part to the gathering darkness. The riflemen struggled to expand the bridgehead under constant machine-gun fire and air attack throughout the next morning. At 1 pm, just as Model arrived at Audoersch’s command post, German bombers hit the dominant Soviet positions on the high ground overlooking the river, obliterating them. The engineers immediately set about building a combat bridge while the riflemen continued to expand the bridgehead as best they could.

Sixteen miles to the west, the 4th Panzer Division was in a similar situation. Early on September 7, its tanks had set upon an enemy assembly area just north of the Seim bridge at Baturin. They destroyed some 30 artillery pieces, 13 antitank guns, and six tanks. The action, however, alerted the bridge guards. This span was also blown up. At 4 am on September 8, the 3rd Panzer Division engineers completed a combat bridge at Melnya, and both divisions’ motorized units began to cross there.

In Moscow, Zhukov was again counseling Stalin to pull back all Southwest Front troops to the eastern bank of the Dneiper and send all available reserves to the Konotop area to defend against Panzer Group 2. He also continued to insist that Kiev would have to be abandoned. The next day, September 9, in a sign that he might be coming around to Zhukov’s point of view, Stalin ordered the Southwest Front to pull its northernmost Fifth Army and the right wing of the Thirty-seventh Army defending Kiev back to the east bank of the Dnieper and to bend their fronts back to the east to face Second Army and Panzer Group 2 coming down from the north. In the process, they were to continue to protect Kiev.

Early on September 8, the commander of the Southwest Front, Col. Gen. Mikhail Kirponos, requested that forces be sent immediately from Kiev to Romny to block the German penetration there. Stalin said the Southwest Front should hold its positions as ordered and the Briansk Front would handle the penetration at Romny, as ordered. Later that morning, Marshal Semen Budenny, commander of the South West Theater, appealed again to the Soviet High Command, STAVKA, for a withdrawal from Kiev. These repeated requests annoyed Stalin; he accused the commanders of incompetence and loss of nerve and decided to replace Budenny with Marshal Semen Timoshenko. The one move that Stalin did allow was the transfer of two infantry divisions from the Twenty-sixth Army holding the Dnieper line southeast of Kiev to the struggling Fortieth Army. The Fortieth Army was a new formation that had been hastily assembled two weeks earlier and inserted into the Konotop-Shostka area to block Guderian.

When the XXIV Motorized Corps overcame the Soviet forces at the Seim River on September 7-9, it burst through the Fortieth Army and penetrated deeply between the front of the Soviet Twenty-first and Thirteenth Armies, at the seam between the Southwest Front and the Bryansk Front. Model surged south, bypassing Konotop to the west. By the evening of the 9th, his advance guard had reached Korabutovo and captured the two bridges there. Rain began to fall during the night.

With word of the 3rd Panzer Division’s success, Guderian set out for the front early on the 10th. At Geyr’s command post in Ksendovka, he learned that Model had completely bypassed Konotop and penetrated all the way to Romny, that the 4th Panzer Division was attacking Bachmach, and that Das Reich was moving on Borsna. Before setting off for the 3rd Panzer Division, Guderian had Geyr order the 10th Motorized Division to attack and secure Konotop.

Shortly before noon on September 10, after six hours of struggling through the mud and the muck, Major Heinz-Werner Frank’s lead detachment of Model’s division rushed up to the Roman River bridge at the northwest edge of Romny. The Soviet guards there were so startled that at first they did not resist. The lead German vehicles did not stop; they dashed through the cobblestone streets of the small city and grabbed the vital bridge over the Sula River in the center of town.

As more 3rd Panzer Division elements arrived they spread out and combed through the city, clearing it block by block. Enemy air forces attacked relentlessly throughout the afternoon despite the bad weather. By dark the city of clean white houses and cobblestone streets was as one single torch blazing in the night sky, abetted by the numerous new oil wells that the Soviets had ignited on their way out of town. The 3rd Panzer Division now held Romny, 131 miles east of Kiev.

Guderian continued to worry. With his strength dwindling every day, the mud that seemed only to be getting deeper, and his 145-mile-long southeastern flank it was difficult to feel optimistic. At this time the XLVII Motorized Corps was spread thinly, covering the eastern flank north from Novgorod-Seversk. To the south, the XLVI Motorized Corps was pushing southward on the eastern flank. The 17th Panzer Division was holding Gluchov and advancing on Putivl while Grossdeutschland had leapfrogged south and was approaching Shilovka on the Seim south of Putivl.

Both spearhead units were out of touch with the enemy on the 11th, undertaking only patrolling and reconnaissance. The 4th Panzer Division had captured Bachmach late on September 10 against nominal opposition but could go no farther due to lack of fuel. The mud made it difficult for the fighting troops to move, but it was doubly difficult for the supply sections that had to move back and forth from the nearest railhead some 248 miles away. The 3rd Panzer Division captured a small fuel dump in Romny but spent all of the 11th and most of the 12th there consolidating forces and getting a little rest.

Meanwhile, at Army Group South 115 miles to the south, operations were starting to move. At noon on the 11th, a temporary bridge over the Dneiper at Kremenchug was finished in driving rain, and Panzer Group 1’s XLVIII Motorized Corps began crossing into the 17th Army bridgehead as soon as it was dark. The 9th and 16th Panzer Divisions crossed in the pouring rain on a pitch black night. At 9 am on the 12th, Hans Hube’s 16th Panzer Division took the lead and surged north out of the bridgehead. In knee-deep mud the division plowed forward 43 miles in barely 12 hours. The race to close the pocket was on.

News of the Army Group South attack renewed the enthusiasm and vigor of the 3rd Panzer Division troops. Major Frank and his advance guard moved out of Romny at last light on September 12, overran the weak Soviet positions around Romny, and surged south. In less than two hours it captured the intact bridge over the Sula River at Mliny. Lochvitsa, its objective, lay just over a mile beyond the river. By daybreak on the 13th, the Soviets had realized the situation and were bringing heavy pressure to bear on the small bridgehead. Major Frank radioed for help.

Soon a Kampfgruppe built around the 3rd battalion of Panzer Regiment 6 was heading south from Romny to help Frank. Fortunately it had not rained in more than a day, and the roads were drying out so the Kampfgruppe was able to set a rapid pace and reached the advance guard at about 4 pm.

Major Frank and Lt. Col. Werner von Lewinski, the Kampfgruppe commander, decided not to wait for infantry and artillery support but to attack Lochvitsa at once. A small tributary of the Sula snaked around Lochvitsa and joined the river at that point, and several bridges over both water courses needed to be secured. As they began to move out, the Soviets brought heavy fire on the bridgehead from Lochvitsa. Direct fire from antiaircraft guns quickly became the major concern.

By early evening, the Germans had worked their way into the eastern part of Lochvitsa but became bogged down there. The Soviets were firing heavy guns over open sites down every street that the Germans approached. As darkness fell Lewinski pulled his tanks out of the city for fear of individual infantry attacks during the night. The tanks took up screening positions in the defiles and gullies along the edge of town. One battalion of German infantry had arrived during the attack, and it was left to hold the eastern part of Lochvitsa overnight. It defended against several strong Soviet attacks and was able to hold those parts of the city that had been captured.

At 5 the next morning, while the fog still hung low over the rivers and Lochvitsa, Major Ernst Wellmann and his troops moved out to attack pockets of enemy resistance. As they took the large northern bridge they were amazed to find six heavy antiaircraft guns standing in front of the bridge on the far side, wheel to wheel across the width of the street, unmanned. As they dragged the gunners out of their bedrolls in a nearby hut and made them prisoners, the rest of the Soviet troops began withdrawing. By 10:30 am on September 14, Lochvitsa was in German hands.

Guderian was still worried. Despite a dry day here and there, rain predominated and the mud grew worse, air reconnaissance was possible occasionally, and ground reconnaissance impossible. All of his divisions were strung out 20 to 40 miles. Furthermore, the pressure on his spearheads was great. With Panzer Group 1 surging northward, the Soviets would surely put two and two together and rush for the exits from the developing pocket, only increasing that pressure.

After breaking through the stiff Soviet defenses around the Kremenchug bridgehead on the 12th, the XLVIII Motorized Corps encountered much less resistance as it raced north to meet Guderian’s troops. On the 13th, the 9th Panzer Division captured Mirgorod against only moderate resistance while the 16th Panzer Division took the intact bridge over the Sula River at Lukomye and turned north toward Lubny.

Lubny was fiercely defended. The local Soviet commander had called on the populace to defend the city, and they did along with antiaircraft units and formations of the NKVD, Stalin’s secret police. General Hube pulled his units back to reorganize and prepare an attack for the next day. It went in at first light on the 14th and produced savage street fighting. In the end, the ad hoc Soviet force was no match for the panzergrenadiers, and by afternoon Lubny was in German hands with only small pockets of enemy resistance remaining. Thirty miles remained to close the pocket.

The capture of Lubny meant that the last rail and road connections for supplying the five Soviet armies in the pocket were cut. Their only supply now would have to come by air.

At about the same time, a small detachment of the 3rd Panzer Division was moving south from Lochvitsa. Lieutenant Hans Warthmann, commander of the 6th Company of Panzer Regiment 6, had only two tanks and four other armored vehicles at his disposal. His mission was to find the 16th Panzer Division.

The only enemy force that Warthmann met was traveling west to east across his path, trying to escape the encirclement. The Soviets did not want any part of the enemy. Whenever the Germans approached, the Soviets jumped from their vehicles and fled into the fields. Then the Germans raced through.

Warthmann’s little group crossed the Sula River over an intact bridge near Luka at about 4 pm and then followed the east bank southwest toward Lubny. It was just getting dark as it crested a small rise and the troops could suddenly see the silhouette of a city in the distance and hear the crack of small arms fire. This must be Lubny. But where was the enemy, and where were the friendly troops?

Warthmann scanned the skyline through his binoculars for a few moments and then cautiously moved on. He soon approached a small creek that was not fordable and began to look for a bridge. A small bridge was spotted, and it would have to do. As he approached, the bridge was blown sky high. The Germans had crossed many small bridges this day, and this was the first one that had been defended. Suddenly, gray-clad figures jumped up from the underbrush and rushed toward the blown bridge waving their arms frantically. They were covered in dirt with stubbly beards. They were men of the 2nd Company, Panzer Pioneer Battalion 16, of the 16th Panzer Division. It was 6:20 pm on September 14, and the pocket had been closed.

As more troops arrived over the next few days the east side of the pocket was securely sealed. On September 17, Stalin finally relented and gave permission for the Southwest Front to withdraw. On the 19th, Kiev fell to the Germans, and on the 25th fighting in the pocket came to an end. Despite concerted efforts to break out and several external attacks to free the trapped troops, six Soviet armies were destroyed and 665,000 soldiers captured in the worst Soviet defeat of World War II.

Guderian had little time to enjoy this great victory. In less than two weeks the next major offensive of Army Group Center, Operation Typhoon intended to capture Moscow, would begin, and his Panzer Group 2 would play an integral part. After Typhoon’s failure in December 1941, Guderian was relieved of duty by a frustrated Hitler looking for a scapegoat.

Author Jeff Chrisman is a writer, producer, and director of television commercials and corporate video programs. He resides in Columbus, Ohio, and is a graduate of Ohio State University.

Good article and I enjoyed the read.

I’m mystified by this new revisionist wave of the last 10 years or so that has nearly all military enthusiasts convinced the Moscow operation was useless and impossible. Do you have any idea why?

Also there might be a mistake as Guderians rank in the Barbarossa campaign was listed as “Colonel” and not some “General” rank.

Heinz Guderian’s promotions:

01/10/1933 – Oberst (Colonel)

01/08/1936 – Generalmajor

10/02/1938 – Generalleutnant, mit RDA vom 01/08/1937

23/11/1938 – General der Panzertruppe, mit RDA vom 01/11/1938

19/07/1940 – Generaloberst mit, RDA vom 19.07.1940

It is possible the Guderian was, at that time in his career, a Colonel-General!

Yes, Guderian was in fact a Generaloberst (colonel General) at that time.

The article says exactly that 7 lines down (when viewed on my phone) Colonel General Guderian.

Why do you write “The” Ukraine? Do you write or say the Germany, or the Russia, or the Ireland, or the England, or the Brazil?

Yes, one does say the USSR, the USA, the United Kingdom, the Maldives, etc. because these are plural countries, islands, entities.

Imperial and Soviet Russia always sought to “brainwash” people into adding ‘the” before Ukraine because they did not want others to think of it as a country, but rather as an area of Ukraine. Like going to the mountains, or to the beach, or to the shore. This is because they feared Ukrainian nationalism and wanted the world to think Ukraine is just a region of Russia, not a separate country. Ukrainians as a whole do not consider themselves to be Russians.

Therefore, the word “the” should not be used exclusively in referring to the independent country of Ukraine.

I would think it would be obvious that during the time covered by the article Ukraine was not an independent country, and was commonly referred to as the Ukraine.