By Chuck Lyons

In September 1941, during the siege of Leningrad, as the Soviets then called St. Petersburg, Nazi troops overran the Tsarskoye Selo Palace, the former summer residence of the czars in the suburban town of Pushkin. Inside the palace, these German troops discovered something that must have seemed otherworldly to them after they had spent the past 10 weeks marching and fighting in the dust and heat of the Russian summer.

It was a Baroque chamber made completely of amber and decorated with large mirrors and amber carvings of cupids and family crests, nymphs, and monograms. Called, fittingly enough, the Amber Room, the chamber had been created in Prussia in the early 16th century and was later given to Russia’s Czar Peter the Great. In its two and a half centuries of existence it had become famous throughout Europe and had been called, among other things, the “Eighth Wonder of the World” and “one of the world’s most extraordinary works of art.” Its estimated value today is more than $180 million.

The Nazis carefully dismantled the chamber, packed it in crates, and shipped it to Königsberg Castle in eastern Germany, the ancient seat of the Teutonic Knights and the heart of their medieval amber trade. There Erich Koch, head of the Nazi Party in East Prussia, had the room reassembled and advertised it as a “German possession, now at last restored to its rightful owners.” In 1945, however, as Germany’s war was ending with the Allies squeezing the Nazis from the east and west, the room was once again dismantled, packed in 24 crates, and stacked in the courtyard of the castle. From there it disappeared, and it has not been seen since.

Amber is fossilized tree resin that is about 44 million years old. Up to 90 percent of the world’s supply is mined along the southern shore of the Baltic Sea.

For millennia, resin had flowed from coniferous trees and settled on the forest floor in Eastern Europe. Then as the Earth’s plates moved and ice sheets formed and melted, the area became flooded and the Baltic Sea formed. From early times, bits and pieces of amber, which has been called the “gold of the North,” were torn from the sea floor and washed ashore to be picked up and treasured. It has been found most often on the east coast of the Baltic Sea from the current site of Danzig in Germany north to Estonia.

Eventually an amber trade grew, and mining operations, first by men wielding large nets, were developed. Often these net wielders were slaves in the employ of the Teutonic Knights, an order that grew rich on amber. By the 13th century, the knights controlled the trade and had centered their amber commerce at the newly built Königsberg Castle on the Pregel River. By the 16th century, however, with the Protestant Reformation sweeping Europe, the Teutonic Knights renounced their Catholicism, becoming Lutherans and forming the Teutonic order’s Prussian territories into the Duchy of Prussia as a Polish fief. Eventually Prussia gained independence from any feudal obligations, and in 1701 Elector Frederick III was crowned as Frederick I, the first King of Prussia.

Frederick married his second wife, Sophie Charlotte, a great granddaughter of England’s James I, in 1684, and she invested most of her time and effort in artistic pursuits, one of which was to make the Prussian capital of Berlin shine. In 1696, when Frederick was still Elector, she asked the sculptor Andreas Schluter to work on the interior redesign of the royal palace. Schluter began searching in the palace’s storage cellars and found a number of chests filled with amber. He later claimed it was the largest collection of amber he had ever seen in one place.

After discovering the amber in the palace’s cellars, Schluter conceived the idea of using it to create an entire room made of the precious substance. He developed a design for such a room, a complete chamber decorated floor to ceiling with amber panels backed with gold leaf and covered with mirrors, polished mosaics, carvings of nymphs, cupids, and angels, coats of arms, monograms, and inlays, some so small the observer needed to use a magnifying glass to view them. He hired the Danish carver Gottfried Wolfram and put him to work developing the Amber Room. Over the next several years, Wolfram evolved a method of bonding amber slivers into larger pieces and created some 46 massive amber panels, a dozen of them 12 feet high.

In 1705, however, Sophie Charlotte died, and Schluter fell out of favor. He was banished from court, and the carver Wolfram was fired. In 1713, Frederick I died and was succeeded on the throne by his son, Frederick William I, a no-nonsense man much more interested in building a strong Prussian army than he was in tinkering with amber panels.

The unfinished Amber Room remained at the Berlin City Palace until 1716, when Russia’s Peter the Great entered the tale.

That year Peter visited the court of Frederick William and talked of the unfinished Amber Room. Peter had always been an admirer of the gold of the north, and Frederick, uninterested in the amber anyway, gave the amber panels Wolfam had assembled and carved to Peter as a gift.

The amber panels were carefully disassembled, packed in crates, and loaded on eight carts that slowly moved their precious cargo to Peter’s summer palace in the Russian capital of St. Petersburg. When the panels arrived, some pieces were broken and others were missing.

Besides the broken and missing pieces, no one could seem to figure out how the remaining panels should fit together, and no instructions from the banished Danish carver who had created the panels or the Prussian sculptor who had conceived them could be found.

The amber was stored in the palace and languished there for almost 20 years after Peter’s death in 1725.

In 1743, however, Empress Elizabeth ascended the Russian throne, and one of her first acts was to have the amber transferred to her new winter palace on the River Neva where the Italian sculptor Alexander Martelli was put in charge of assembling the panels and installing them in a large hall at the palace. Somehow, Martelli solved the puzzle of assembling the chamber.

Elizabeth was still dissatisfied and had the room moved three more times and embellished with additional mirrors and amber mirror frames. Eventually the chamber covered more than 55 square meters, or 188.4 square feet, and contained over six tons of amber. In 1755, however, it was again moved, this time to the palace of Elizabeth’s favorite niece, Catherine, at Tsarskoye Selo. Catherine, who came from the amber mining region on the Baltic Sea, ascended the Russian throne herself in 1767 and eventually became known to history as Catherine the Great.

Czarina Catherine added another 900 pounds of amber to the room, replacing some sections with large windows. She also commissioned four stone mosaics corresponding to the senses of sight, taste, touch, and hearing. Visitors to the completed chamber said it “came alive” in candlelight.

The Amber Room remained in splendor until shortly after June 22, 1941, when 99 German divisions, including 14 panzer divisions and 10 motorized divisions, stormed into the Soviet Union along a front from the Baltic to the Black Sea. For a month, the Nazi blitzkrieg was unstoppable, and in the north the army group under Field Marshal Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb moved closer to its objective, the Soviet Union’s second city of Leningrad.

By mid-August, German troops were approaching the city, their artillery and aircraft attacking it. By the end of the month, the battle for Leningrad had become a siege.

A Soviet counterattack in January 1942 failed to break the siege, and the fighting continued until January 1943 when Soviet forces executed a plan to open a land corridor to the besieged city. After six days of heavy fighting, the corridor was established with German forces cleared from the southern shore of Lake Ladoga for several miles, but it was not until a year later that the Germans were driven 50 miles from the city and the siege was considered broken.

By then, however, it was too late for the Tsarskoye Selo palace and the Amber Room.

Tsarkoye Selo, translated as “Czar’s Village,” is part of the town of Pushkin situated 24 miles south of Leningrad’s center. In September 1941, during the early stages of the siege, German forces overran Pushkin and plundered a number of Soviet and Russian national monuments there. Among them was the czarist place that Catherine the Great had built in the 18th century. Pushkin remained in German hands until its liberation by the Red Army on January 24, 1944.

As the Germans approached Pushkin and Leningrad in 1941, the Soviets took steps to save as many of the treasures housed in the cities as possible, including the Amber Room. The curators of the chamber first tried to disassemble the room’s panels, but over the years the amber had dried and become brittle. As attempts to remove it were undertaken, the fragile amber began to crumble. Rather than moving it and subjecting the amber to further damage, a false room was constructed inside the amber room’s walls in an attempt to hide it. Some sources assert that the amber was simply covered by wallpaper.

When the Germans occupied Tsarskoye Selo, probably already aware of the famous chamber and its location, they discovered the Amber Room and were able to disassemble it under the supervision of a pair of experts. The amber panels, mirrors, cherubs, and nymphs were carefully packed. On October 14, 1941, Rittmeister Graf Solms-Laubach, who was in charge of the disassembly and packing, ordered the 27 crates shipped to Königsberg for display in the town’s castle.

The Amber Room, he concluded, was going home.

The chamber was carefully reassembled at Königsberg and became another trophy of the Third Reich’s military prowess. On November 13, 1941, the newspaper Königsberger Allgemeine Zeitung reported on the opening of an exhibition of part of room at the castle.

By the end of 1943, however, Königsberg was coming under increasingly frequent Soviet bombing attacks. The room was again disassembled, and the crates were stored in the castle’s cellar. In January 1945, as the war continued turning against Germany, Koch received instructions to load the amber panels into 24 strongboxes and prepare them for shipment.

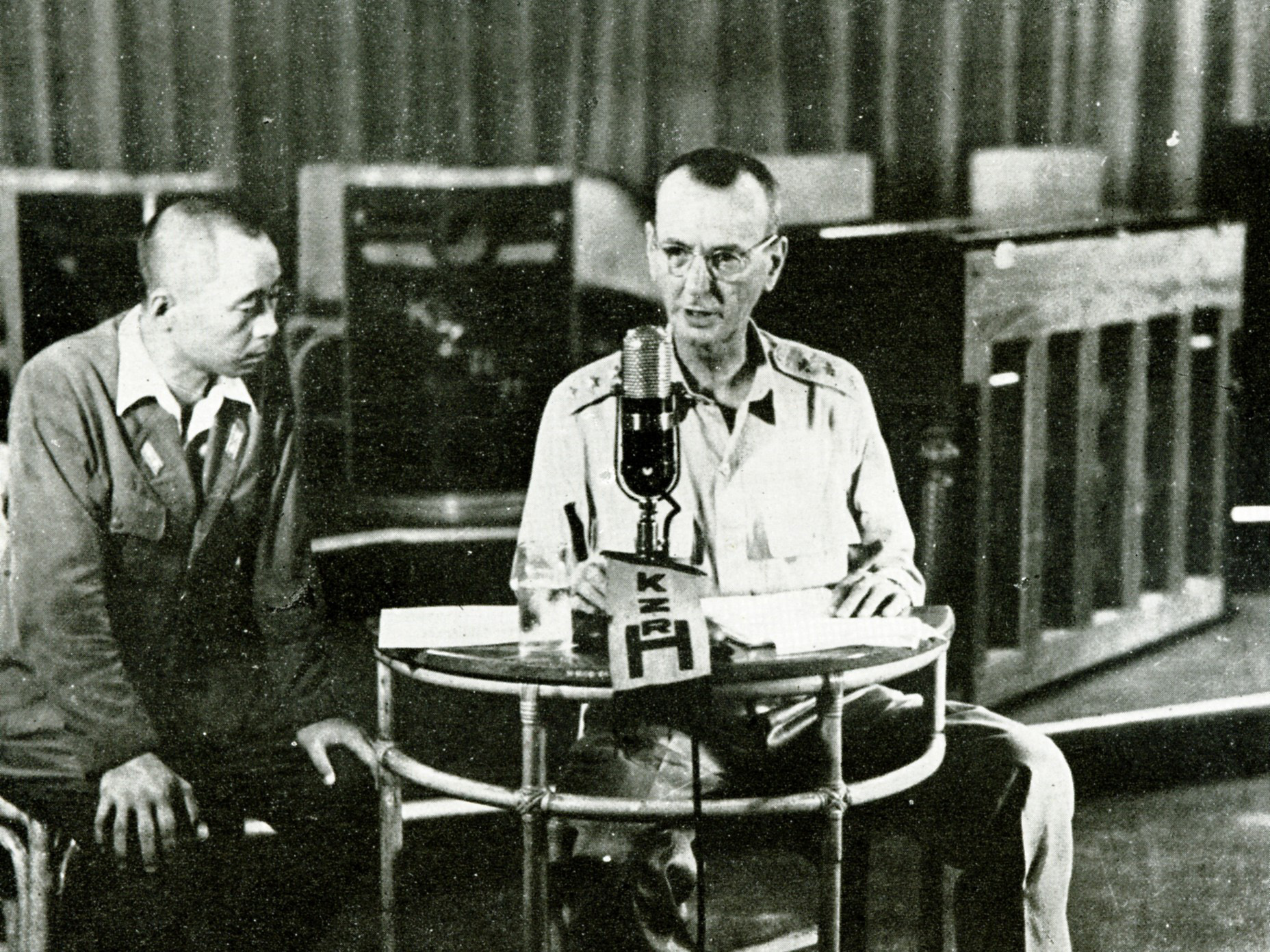

was displayed until looted by the German military.

“As soon as this is done,” Koch wrote, “I shall evacuate the panels to Wechselburg, near Rochlitz in Saxony.”

It is known that the packing was completed on January 15, 1945, and that the crates were piled in the courtyard of the castle. But the trail ends there. The crates are believed to have never arrived in Wechselburg, and whether they even left Königsberg is unclear, although some eyewitnesses have reported seeing them stacked at a railroad station.

Over the years a number of extensive searches, including several by the Soviet Union, have proved fruitless. In 1997, a piece of the room was found. An Italian stone mosaic known to have been part of the room turned up in western Germany. It was owned by the family of a soldier who had helped pack the Amber Room at Königsberg in January 1945, and this soldier’s souvenir sheds some light on the fate of the Amber Room. In 1998, two separate teams also claimed to have found the Amber Room, one in a German silver mine and the other in a lake in Lithuania, but neither was able to produce the room itself.

As recently as 2008, another alleged discovery of the Amber Room was announced. Radar scans were reported to have detected a large amount of metal believed to be too dense for copper in an abandoned copper mine in Deutschneudorf, Saxony. Some observers, including Hans-Peter Haustein, mayor of Deutschneudorf, claimed the mine was the burial site of the Amber Room.

Another theory put forth is that the amber was taken from the castle’s courtyard in early 1945 and again hidden in its cellars. It was then destroyed when the castle was heavily bombed by the Royal Air Force. This theory is supported by the conclusions of two studies made by British investigative journalists Catherine Scott-Clark and Adrian Levy and by Soviet investigators. Both studies concluded that the Amber Room was most likely destroyed when Königsberg Castle was burned shortly after its surrender.

Another theory suggests that the room lies with other Nazi-plundered treasure at the bottom of 350-foot-deep Lake Toplitz in the Austrian Alps, where senior German officers are known to have retreated as the Allies advanced through Germany. It has been claimed that these officers transported large boxes by truck and horse-drawn carriage to the edge of the lake and sank them.

Other investigators have speculated that the Amber Room was hidden 2,000 feet below ground in a salt mine near Gottingen, Germany, that has since been flooded. Supporting this last theory is a coded message sent to Berlin in January 1945. It reads, “Amber Room, operation completed, object is stored in B. Sch. W.V.” This message may refer to the B shaft of a mine near Gottingen known as Wittekind Vollpriehausen.

After the war, a full reconstruction of the Amber Room was created at Tsarskoye Selo based on 86 black and white photographs taken of various fragments of the room. The project was begun in 1979, and by 2003 the work was largely completed. Russian President Vladimir Putin and German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder dedicated the room at a celebration of the 300-year anniversary of the city of St. Petersburg. A miniature model of the room, made of original East Prussian amber, has also been constructed and is on display at Kleinmachnow, Germany.

The fate of the original Amber Room, however, remains one of the great mysteries of World War II.

Author Chuck Lyons has contributed to WWII History on a variety of topics. He resides in Rochester, New York.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments