By John E. Spindler

Jan Zizka belongs to the elite group of leaders who never lost a battle. He was born on or around 1360 in the village of Trocnov in the Kingdom of Bohemia. During his early life he lost an eye. Although it is not known exactly how the accident happened, it is believed that it occurred either as a result of a child-hood injury or an adolescent fight.

During unrest in Bohemia, Zizka served John Sokol, a prestigious Bohemian noble. Sokol served on the staff of Polish King Wladyslaw II at the Battle of Grunwald fought on July 13, 1410. The epic battle drew nobility and knights from far and wide, and therefore it is entirely possible that Zizka was present with Sokol to assist the Polish-Lithuanian army in its fight against the Teutonic Knights. The following year Queen Sofia of Bohemia hired Zizka as a bodyguard. It was in her service that Zizka met priest Jan Hus and became a devout follower of the Bohemian reformer.

Hus had a large following in his native land. He condemned papal authority insisting that supreme authority rested in the Bible. Outspoken in his criticism of clerical corruption, the relentless reformer believed that all people should be able to receive both forms of Communion; that is, both bread and wine. At the time, only clergy were permitted to receive Communion in the form of wine. Provoked by his protests, the Church excommunicated him in 1411. The following year, he composed his greatest work, De Ecclesia(On the Church).

In 1414, Hus was summoned to appear before the Council of Constance to defend his position. He agreed to abide by the summons provided that Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund, who was king of the Germans, Hungarians, and Romans, and the host of the council guaranteed his safe passage. Imprisoned and placed on trial for heresy when he appeared before the Council the following year, Hus ultimately was condemned as a heretic and sentenced to death. He was burned at the stake on July 6, 1415.

Hus immediately became a martyr to his followers, who were known as Hussites. They blamed Sigismund for the awful fate that befell Hus. Emperor Sigismund despised the Hussites and wanted to eradicate them. At the time, Bohemia was ruled by Sigismund’s brother, King Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia. A period of internal strife ensued in Bohemia in which the peasant Hussites drove out Catholic priests.

In 1417, the Council of Constance issued a blanket excommunication of all Hussites. To protect themselves against persecution, the Hussites organized themselves and established hilltop strongholds. One of these fortresses 50 miles south of Prague was called Mount Tabor. It became home to a radical faction of Hussites known as the Taborites.

Zizka joined forces with Hussite priest Jan Zelivsky. On July 30, 1419, the two men led a group of armed protesters through the streets of Prague to New Town Hall where they demanded the release of imprisoned moderate Hussites known as Utraquists. When the pro-Catholic councilors refused to release them, the Hussites threw the 13 councilors out of the window. The event is known as the First Defenestration of Prague. Those who survived the fall were killed. King Wenceslaus, who was visibly shaken by the rioting, died two weeks later. Sigismund was next in line for the throne. The Hussites were prepared to go to war to prevent him from becoming their king. Sigismund’s supporters in Bohemia were known as Royalists.

Following the riot, Zizka was elected captain of the Hussite force in Prague. In October he and his troops seized control of Vysehrad Castle on the south side of the city. On the north side, Queen Sophia, who Sigismund had appointed as regent until such time as he could be crowned king of Bohemia, held Hradcany Castle. Her sympathies were with the Hussites, and she wanted to avoid armed conflict at all costs.

The Utraquists subsequently entered into a truce with Queen Sophia whereby they turned over Vysehrad Castle to her. The decision marked a breach between the moderate Utraquists and the conservative Taborites. Zizka objected to the truce, and he led the militant Taborites southwest to Pilsen where he worked with Father Nicholas Koranda to fortify the stronghold so that it would be able to resist the ruling Catholics.

Zizka initiated operations against the Royalists by besieging the town of Nekmer. In response, Lord Bohuslav of Svamberg assembled a force of 2,000 cavalry and led it against Zizka’s 400 infantry. Bohuslav and his men expected an easy victory since they outnumbered the Hussites five to one. Zizka deployed his hand gunners and crossbowmen in and around seven wagons that he used to form a strong defensive perimeter. When Lord Bohuslav’s cavalry charged the Hussite war wagons, they were repulsed with heavy losses. The noise, smoke, and effectiveness of the guns shocked the Royalists. The battle was significant because it marked the first recorded use of war wagons by the Hussites.

While Zizka’s Royalist opponents could call on veteran armies, the Hussites had to make do with peasant militia. In the Middle Ages not only was there a lack of military discipline, but tactics for both infantry and cavalry basically consisted of a mass charge. Zizka insisted on rules, drills, and a strict code of conduct for those who fought under him.

Zizka made do with what was readily available to him and his troops. Since peasants threshed grain for a living, Zizka transformed their threshers into flails. This gave him an inexpensive weapon with which to arm the peasants. Hussite funds were used to purchase crossbows, hand guns, and halberds. What his peasant infantry needed to stand up to cavalry in battle was protection.

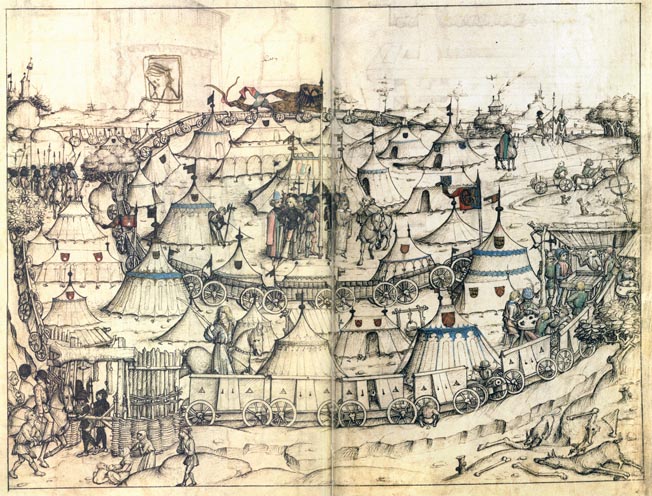

Zizka made enhancements to four-wheeled baggage wagons to make them suitable for warfare. Stout planking was added so the walls sloped outward slightly. Another panel of planking, which was fastened by ropes, was draped over the left side to protect the wheels. A plank also was hung below the wagon to stop the enemy from crawling under it. Loopholes were cut through which the crossbowmen and hand gunners could fire their weapons. On the right side of the wagon was a narrow door fitted with a ramp. A wagon crew consisted of 20 soldiers: two armed drivers, six crossbowman, two hand gunners, four flail men, four halberdiers, and two pavisiers. The fire from the crossbowmen and hand gunners would unhorse the charging cavalry, then the Hussite soldiers, armed with staff weapons, such as flails and halberds, would slash and hack the unhorsed cavalrymen to death.

For battle, Zizka developed the tactic of arranging the wagons in a defensive square known as a wagenburg, meaning wagon fort. The Goths, Byzantines, and Mongols all used some type of wagon fort. The gaps between wagons were plugged either with small cannons or by pavises. Within the square were the horses, supplies, cavalry, and infantry.

Zizka had a keen eye for terrain. He sought in every situation to occupy the highest elevation possible. He preferred hills with steep slopes so that the enemy’s heavy cavalry would be compelled to dismount and ascend the slopes on foot.

When King Wenceslas died in August 1419, Sigismund prepared to secure the crown of Bohemia by force. To facilitate and sanctify this effort, Pope Martin V issued a papal bull on March 17, 1420, calling for a crusade against the Hussites. In response, the Hussites turned to Zizka to lead them in battle against Sigismund’s powerful Imperial army.

Hussite moderates in Pilsen persuaded Zizka to make a deal with Bohuslav rather than have Pilsen besieged and possibly destroyed by a Royalist army. On March 22, 1420, Zizka led 400 Hussite soldiers with 12 war wagons and a large number of women and children away from Pilsen. Under the terms of an agreement, Bohuslav had granted safe passage to the small Hussite force. But his intentions were entirely disingenuous. The Royalists spread word throughout the region that the Hussite force was marching overland and vulnerable to attack.

The Hussites were bound for Tabor. They had just forded the Otava River near Sudomer three days later when scouts reported a large Royalist force bearing down on them. The Royalist army was led by Henry of Hradec and Peter of Sternberg. Zizka parked his wagenburgon a dam between two fish ponds that had been drained for the winter.

The initial attack by the Royalists was repulsed. The two leaders conferred and devised a different plan. Henry of Hradec’s men would launch a dismounted attack against the wagenburg,while Peter of Sternberg’s mounted troops would attempt to outflank the Hussites through the fish pond on the Hussite right. The attack sputtered when Sternberg’s cavalry became mired in the muck. All further assaults were repulsed. The Battle of Sudomer further enhanced Zizka’s reputation. He was no longer merely respected; he was revered.

While Sigismund was assembling a mighty host with which to secure the throne of Bohemia, Zizka answered the call of the townspeople of Prague and led 9,000 Hussite soldiers to the Bohemian capital where he arrived on May 21. Zizka studied the possibilities available for a strong defensive position given that the both of the city’s castles were in Royalist hands. Importantly, the Hussites controlled the walled New Town on the east side of Prague. Zizka determined that Vitkov Hill, which controlled the eastern approaches to the city, was a crucial position worth occupying and defending. His troops strengthened an old watchtower atop the hill ans constructed a palisade and rampart next to it. Sigismund arrived the following month with 80,000 crusaders—45,000 infantry and 35,000 cavalry that had been recruited from all parts of the Holy Roman Empire. Many were mercenaries who felt no real sense of allegiance towards Sigismund, though.

To successfully besiege the New Town, Sigismund knew he had to control Vitkov Hill. On July 14, he ordered 8,000 cavalry to drive the Hussites from the key position. The narrowness of the hill, which was only 100 yards wide, enabled the defenders to hold on until Zizka launched a surprise flank attack. The Crusaders panicked and streamed downhill onto Hospital Field, a level plain alongside the Vltava River. Another force of Hussites sallied forth out of the New Town and routed the crusaders. With his mercenaries unwilling to stay longer, Sigismund departed Bohemia after having himself crowned king of Bohemia in St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague’s Catholic-controlled Hradcany Castle.

In the first half of 1421, Zizka won many battles against Sigismund’s Bohemian allies with his wagenburgtactics. During the siege of Rabi in late June, Zizka was struck in the face by an arrow, blinding him in his good eye. For the remainder of his life, the blind general relied on detailed information about the enemy and terrain to craft his battle strategies.

The second anti-Hussite crusade gained momentum in the late summer of 1421. A large army of German crusaders entered Bohemia from the west on August 28. They besieged the key town of Zatac on the Eger River in northwestern Bohemia on September 10. The Hussite garrison repulsed a half dozen assaults on the town. But when the Germans learned that Zizka was marching to the town’s relief, they withdrew on October 1 despite their superior numbers.

Sigismund’s army entered Bohemia in October, but the emperor waited so long for additional troops to join his army that Zizka’s 12,000 troops were able to occupy Kutna Hora and improve its defenses. After Prague, Kutna Hora was the most important town in Bohemia as it was the center of the Bohemian silver mining industry.

Although Sigismund was present with his army, day-to-day operations were handled by an Italian mercenary captain named Philip Scolari. Sigismund’s 50,000-strong crusading army arrived at Kutna Hora on December 21 to find a Hussite wagenburgdefending it. Scolari’s heavy cavalry made repeated charges against the stout wagon fort. Hussite cannons inside the wagenburgroared to life, inflicting great carnage on the crusaders.

Realizing force alone could not defeat the Hussites, the crusaders intrigued with sympathetic townspeople who opened a gate to a column of crusader cavalry that entered the town from the south. Just when it seemed that Zizka might be beaten for the first time, the clever Hussite commander decided to launch a surprise attack at night against that portion of the crusader battle line where Sigismund’s headquarters was located.

Zizka attacked the crusaders in the early morning hours of December 22. The entire Hussite force advanced toward the north portion of the crusader line. They were heading straight for Sigismund’s camp. Since night fighting was practically unheard of in the Middle Ages, Zizka used the confusion and fear created by hand guns and cannons to open a breach in the enemy lines large enough for the Hussites to pass through to safety. Stopping a short distance later, another wagenburgwas established on Kank Hill to await the Hungarians. But Sigismund was content to retain possession of Kutna Hora and did not pursue the retreating Hussites.

In the sharp skirmishes that followed, the Hussites defeated the Imperialists multiple times in central Bohemia in early January 1422. Hussite maneuvering eventually compelled Sigismund to abandon Kutna Hora altogether. Although Scolari and other officers advised Sigismund not to engage in further battles with the Hussites, he ignored their advice. The crusaders formed for battle at Habry on January 8. When the Hussites attacked, the crusader army immediately fled the field.

The crusader army marched south toward Moravia with the Hussites on its heels. When Sigismund’s main body reached the town of Nemecky Brod, it had to cross the Sazava River. Leaving behind a rear guard to impede the Hussite pursuit, the emperor continued on to Moravia. A bottleneck eventually developed at the bridge over the Sazava as refugees joined the fleeing columns of soldiers. Having grown impatient at the long delay, a force of Hungarian cavalry decided to ride across the frozen river. Some managed to make it across, but the weight of men and horses eventually caused the ice to break. When it did, 548 Hungarian cavalrymen plunged to an icy death.

In October 1422, Zizka had become alienated from the Taborites and had taken up with the Orebites. Even though he allowed himself to become embroiled in Hussite politics, he continued to conduct small operations against Catholic Bohemians who opposed the Hussites.

On April 27, 1423, Zizka fought a battle at Horice against Catholic Royalist forces led by Cenek of Wartenberg. The forces were evenly matched at approximately 3,000 troops each; however, the Hussites had 120 war wagons to augment the strength of their force. Zizka deployed his wagenburgon high ground, and Cenek’s cavalry dismounted to assail it. Zizka’s cannons tore gaping holes in the Catholic ranks. Zizka then ordered his small cavalry force to attack the Catholics. Their charge routed the enemy. Between campaigns Zizka found time to complete a military treatise, Statutes and Military Ordinances of Zizka’s New Brotherhood, which codified his beliefs for the Hussite army.

In January 1424 Zizka opened a new campaign against the Catholic Royalists. He moved against Pilsen in May with 7,000 foot soldiers, 500 cavalrymen, and 300 war wagons. As Zizka’s power and influence grew uncomfortable for certain elements in Prague, the conservative Utraquists entered into an alliance with the Catholic Royalists. This coalition force outnumbered Zizka’s and marched to engage him in the first week of June. Approximately 15 miles northeast of Prague near the town of Kostelec, which is situated along the Elbe River, the two sides met in battle. Zizka deployed his wagenburgand held out for several days against forces who knew his tactics.

In the mistaken belief that they had at last defeated the great Hussite commander, the Utraquist-Royalist force awoke on June 4 to find Zizka and his soldiers had disappeared into thin air. Although it is not known for certain how he did this, one theory is that an ally of his arrived with boats to ferry him and his men across the river. Zizka then marched on Caslav with the Utraquist-Royalist force in pursuit. He made a stand at the fortress of Malesov.

He deployed his wagenburgatop a high plateau alongside the Malesovka River. On June 7, while the enemy was in the midst of fording the river, Zizka launched a combination of gunfire and stone-filled wagons down the slope. His foot soldiers advanced behind them. The tactic disrupted the entire enemy force, which is believed to have lost upward of 1,400 Royalist men in the battle. Zizka’s decisive victory crippled Prague’s military capabilities for years to come.

Zizka and the townspeople of Prague eventually reconciled their differences. They signed an agreement on September 14 known as the Peace of Liben through which they agreed to refrain from future hostilities.

Zizka seemed satisfied with the reconciliation. He soon organized a force designed to liberate Moravia. The motley army of various Hussite factions numbered 20,000 men. On October 3 it marched against the Moravian capital of Brno. Just before it crossed the border, Zizka inexplicably stopped to besiege the Royalist castle at Pribyslaw. He fell severely ill and died on 11, 1424. Although the exact cause is not known, it was presumed to be the plague.

Jan Zizka inspired those who fought for him to feats unheard of at the time. For example, they launched surprise attacks at night and fought long campaigns throughout the harsh winter months. He implemented a strict code of conduct among his peasant, lower class troops that enabled them to defeat armies with far greater resources and numbers. Zizka’s mastery of strategy and tactics enabled him to win all of his battles. For these reasons, he is counted among the world’s greatest military commanders.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments